Chops: Intermediate

Theory: Intermediate

Lesson Overview:

• Learn to generate new voicings.

• Experience harmony's gravitational force.

• Explore octave displacement.

This month I’d like to explore several approaches to generating new voicings on the guitar. Harmony is often a mysterious and clouded subject for guitarists. We know the importance of playing interesting and supportive voicings, but the way to go about finding these isn’t always obvious. When I first started getting seriously into jazz and learning how to comp, I was really committed to learning as many voicings as possible. Often I would refer to Ted Greene’s seminal book, Chord Chemistry, as the all-encompassing source of cool chords and unusual shapes. As I worked through the book I ran into a conundrum. I would learn interesting chords, but I wasn’t sure how to apply them in a playing situation. It was as though I was always looking for the right place to try them out. More times then not, the result sounded like I was forcing the chords onto the music—whether it needed them or not—rather than allowing my ear to lead me into the appropriate harmonic territory.

On my newly initiated journey to discover the inner workings of harmony, I came across a few key concepts that really helped me to understand harmony as a living breathing organism rather than a fixed theoretical concept. It started to seem that voicings were no longer something I had to learn and then apply, but rather the consequence of a deeper understanding of the tug of war that exists within harmony’s gravitational force. This realization came largely from a lesson I learned from vibraphonist Gary Burton.

In response to asking him about comping and voicings, he told me that he learned the most about how to construct voicings from guitarist Jim Hall. I was amazed that another instrument looked to the guitar for harmonic direction—we always seem to be the last to know how this stuff works! I was fascinated by what it was he took from Jim’s approach. Because Gary plays with four mallets, he found that the structure of his voicings had more in common with what guitarists play than the larger-structure approach used by pianists. Both vibes and guitar have similar restrictions and therefore note choices become increasingly important. Gary proceeded to show me an exercise he’d developed after checking out Jim Hall, which quickly became an invaluable tool in teaching me how to build stronger voicings.

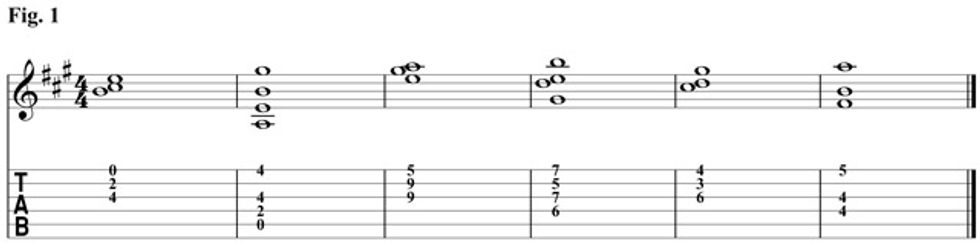

The first step is to pick a tonality—let’s say A major. With this key in mind, you set the metronome to a comfortable tempo for quarter-notes, maybe something like 100 bpm. With these parameters in place, you practice alternating between closed and open voicings within the chosen key.

Just as a reminder, we think of closed voicings as being built with intervals of a third or smaller and open voicings using a fourth or larger. You are essentially improvising chord shapes the same way you improvise melodies. The key to this exercise is that any note in the A major scale is fair game. It isn’t necessary to always play the root, 3rd, or 5th of the chord, and in reality, if you are playing with a bass player or other accompanist, you usually don’t need to double these fundamental pitches. The only guideline to keep in mind is that whenever you double a pitch an octave above or below, it usually has the effect of canceling out the fundamental overtones and results in a weaker overall voicing.

In Fig. 1 you can see an example of something I might improvise using this idea. I began with a closed voicing (B–C#–E) and then move to an open voicing (A–E–B–G) and then alternate between the two all while staying within the key of A. When I first began to practice this, I started to see the given tonality light up across the entire fretboard. It was like all the notes of the scale were bright red and were equal candidates for expressing the given tonality. From this perspective, any combination of notes you play within those seven pitches becomes available to you and keeps your chords sounding fresh and agile. If you improvise voicings like this for 10 minutes a day for a week, two weeks, or a month, you will start to have a completely different sense of how flexible harmony can be, as well as an appreciation for just how many harmonic possibilities exist on the guitar.

Another exercise that helped me to perceive harmony as a flowing and moving phenomenon rather than a static event, involves looking at things from a purely mechanical point of view. Not only is it important to hear the way harmony works, but it can be helpful to train your hands to feel comfortable with adjusting to constantly changing harmonic terrain.

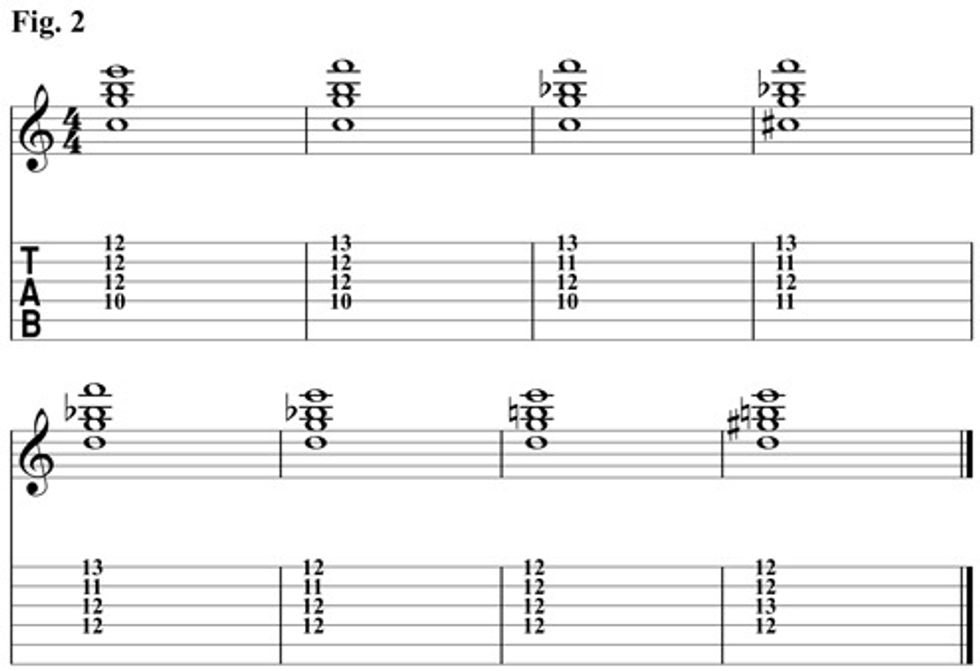

In Fig. 2 we begin with a chord shape, in this case Cmaj7. Again, we set the metronome to a comfortable tempo and practice moving one note either up or down every four beats. Like a spider crawling up the neck, the goal with this is to work your hand all the way up the neck and then back down in a fluid manner. Move all the way to the top fret of your guitar and then back down to the 1st fret. Play around with moving your fourth finger up one fret, then moving your third finger down a fret. Then you can move your first up, your second up, and then your fourth down. It is kind of the fretboard equivalent of taking two steps forward, one step back, however, with this you are encouraged to try different combinations so as to not ever get stuck playing a pattern.

The bonus is that along the way, you might find some cool shapes that you haven’t played before. And when this happens, one thing you can do to maximize the results of your discovery is to isolate the newly discovered chord, find out what tonal center it belongs to—often there are many—and move it diatonically through the appropriate scale.

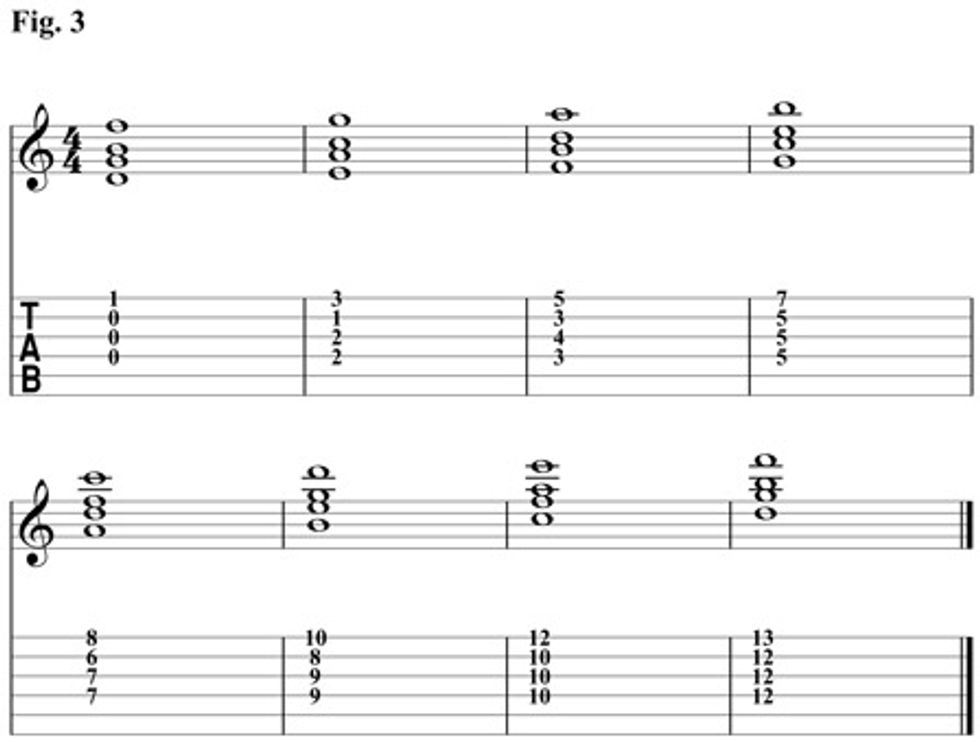

For example, in Fig. 3 we start with a D–G–B–F voicing, which can be seen as the 9th, 5th, 7th, and 4th degrees, respectively, in the key of C. You can then move each note up one step in the scale and continue this sequence up and down the scale to find as many new voicings as there are notes in the scale.

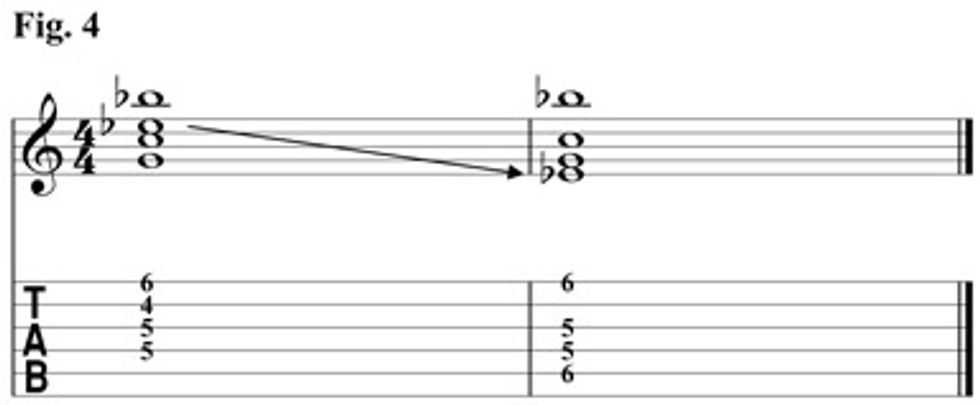

One final idea to play around with when working on new voicings: Apply octave displacement, as shown in Fig. 4. I learned this from the great guitarist Steve Kimock, who in our lessons used to have me practice voicings in all the possible octaves of the guitar. This contributed to my understanding the fretboard and allowed me to see that every voicing can be totally transformed by simply relocating to a new register. Additionally, you can play around with moving only one or two notes up or down an octave to alter the sound. Variation is the heartbeat of creative chord construction and this lends itself beautifully to the guitar.

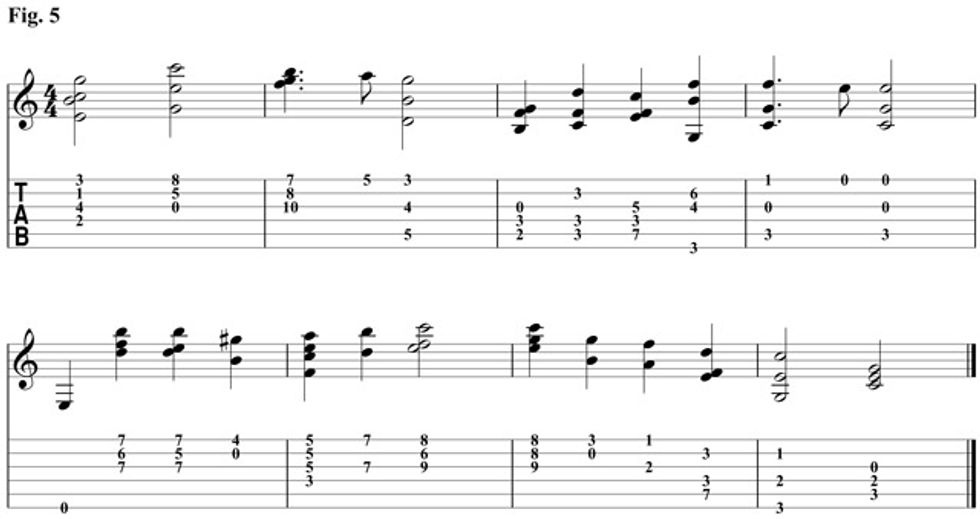

For an example of how all of these concepts can be applied to a tune, in Fig. 5 I’ve illustrated how I might comp over the form of Elizabeth Cotten’s masterful classic, “Freight Train.”

The key that unlocks all these methods of exploring harmony on the guitar is understanding that chords don’t ever have to be final. Every chord can be viewed as arrested motion—or melodies in transit. A four-note voicing is really four melodies that are coming from somewhere and on their way somewhere, and if you let the melodic development of each internal voice suggest what chord to play next, your harmonies will always be relevant to what came before. This approach will help your comping sound like an integrative musical statement in and of itself, independent yet supportive of everything else that is going on.

Julian Lage is one of those rare musicians who

feels equally at home in acoustic and jazz circles.

He has been a member of legendary vibraphonist

Gary Burton’s group since 2004, and

also regularly collaborates with pianist Taylor

Eigsti. Lage’s latest album, Gladwell, reflects

his wide-ranging musical interests and talents

by incorporating chamber music, American folk

and bluegrass, Latin and world music, traditional

string-band sounds, and modern jazz. For

more information, visit julianlage.com.

Julian Lage is one of those rare musicians who

feels equally at home in acoustic and jazz circles.

He has been a member of legendary vibraphonist

Gary Burton’s group since 2004, and

also regularly collaborates with pianist Taylor

Eigsti. Lage’s latest album, Gladwell, reflects

his wide-ranging musical interests and talents

by incorporating chamber music, American folk

and bluegrass, Latin and world music, traditional

string-band sounds, and modern jazz. For

more information, visit julianlage.com.