This month’s topic is EQ. I’d say we’re opening a can of worms, except it’s more like opening a shipping container stuffed with 10,000 worm cans.

It’s tough to talk about—let alone teach—EQ techniques, because almost nothing is true 100 percent of the time. Take the common sentiment that the less EQ you use, the better: Yeah, that’s good advice in most cases—adding overstated EQ tends to make tracks sound artificial and/or harsh. But what if “artificial” and “harsh” are the best expressive choice?

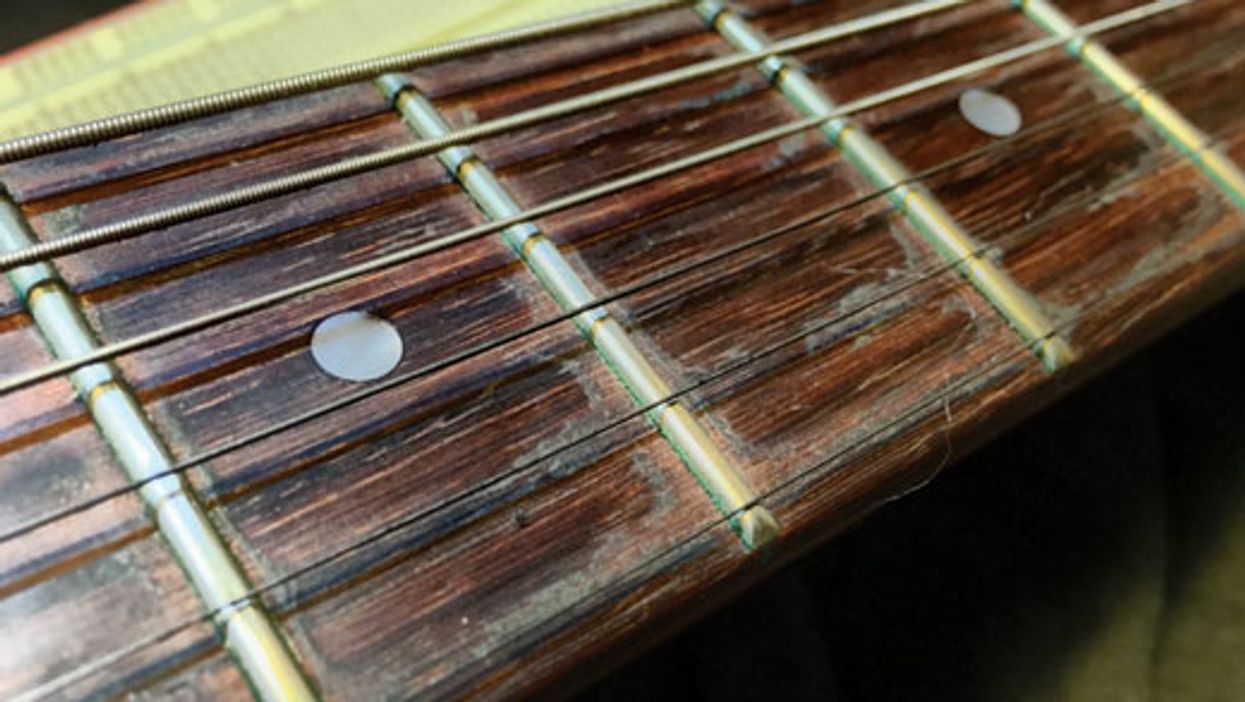

What about all those great ’60s guitars mixed with blistering high-end EQ? (Beatles and Byrds spring to mind.) Or parts engineered to sound as small and claustrophobic as possible? (Think Pink Floyd or PJ Harvey.) Or the eerie, not-found-in-nature equalization used by Nine Inch Nails and other noisemakers? There are countless exceptions to the so-called rules.

So instead of dealing in rules, we’ll talk options. We’ll cover some common EQ techniques, and then venture into more radical scenarios. But first, here’s the quickest and dirtiest intro to EQ principles ever. (If you know this stuff already, you might want to bail now and tune in next month, when we get into some interesting case studies.)

Good news for old guitarists with bad ears: You can have severe hearing loss and still perceive the entire frequency range of an electric guitar.

Basic EQ lingo.

To gain a thorough understanding of EQ, Google “equalization” (or “equalisation” if you’re a Brit), the word from which the letters “EQ” are plucked. To gain a superficial understanding that can get you through most situations, read on!

- Equalization means adjusting specific frequencies within a sound—adding or subtracting treble or bass, or emphasizing/deemphasizing specific frequencies in the middle.

- We measure musical frequency—how high-pitched or low-pitched a sound is—in Hertz (Hz). The hearing range of a healthy young person is approximately 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz (20 kHz). If you’re middle-aged, a Motörhead roadie, or both, your upper limit is probably much lower.

- Most musical sounds contain many individual frequencies. The lowest-pitched frequency is called the fundamental. The fundamental of a standard-tuned low E string, for example, is approximately 82 Hz, but there are other frequencies—overtones—that ring out far above the fundamental. If you filter that 82 Hz fundamental from a recording of that low E, the sound gets thin and tinny, but doesn’t vanish.

- If you transpose a note up an octave, the frequency of its fundamental doubles. Drop it an octave, and the frequency is halved. Example: The 440 Hz tone we tune to is the same pitch as the A at the 5th fret of your 1st string. The A at the second fret of the G string is 220 Hz. The open A string is 110 Hz. And a bassist’s open A is 55 Hz, below the guitar’s range. The fundamental of your high E string at the 17th fret is 880 Hz.

- Good news for old guitarists with bad ears: The frequency range of an amplified electric guitar extends from somewhere around 80 (depending on how you tune your low string) to somewhere around 4.5 kHz—typical guitar speakers simply don’t transmit higher frequencies. You can have severe hearing loss and still perceive the entire frequency range of an electric guitar. The range of an acoustic guitar extends much higher, however.

- Loudness (or amplitude, to use the more science-y term) is measured in decibels (dB). Gently rustling leaves might measure 20 dB, while a jet takeoff can reach 150 dB. The threshold of pain is approximately 130 dB. The loudest rock concerts on record exceed it. In mixing, most EQ adjustments are of only several dB, though they sometimes reach ±20 dB or more.

- Bandwidth refers to the breadth or narrowness of the affected frequency range. Most guitar and amp tone controls have relatively wide bandwidths. Narrow bandwidths are sometimes called notches. Bandwidth is also called “Q.”

- Filtering is the process of removing particular frequencies. A low-pass filter (LPF) cuts highs, letting lows pass through for a darker sound. A high-pass filter (HPF) does the opposite, cutting lows. A band-pass filter affects a particular “slice” of frequencies. The width of the slice varies according to the filter’s—wait for it—bandwidth.

- An EQ tool that lets you select the target frequency and its bandwidth is said to be parametric. If you can select the frequency, but not the bandwidth (as on many active bass guitar tone controls), we call it quasi-parametric.

Take the EQuiz!

After reading the above, do real-life EQ utterances like these make sense?

“My guitar sounds a little dark—can you give me +2 dB at 2.5k?”

“Yow! I get howling feedback when I step near the monitor. Can you notch out a little 1k?”

“The bass player just went into anaphylactic shock! If I drop my low E to A, and you pump up that 50 Hz, maybe no one will notice.”

Cool. Now you can talk EQ like a pro.

EQ in your tone chain.

Where do the EQ stages in your guitar’s tone chain fit into the picture? Standard guitar tone controls are low-pass filters. Same with most distortion pedals that have a single tone control. The nature of amp tone controls varies from model to model, but a high-pass bass control, a low-pass treble control, and a band-pass mid control is a typical arrangement. Many electric basses employ quasi-parametric midrange controls, with separate boost/cut and frequency-select controls.

In other words, the EQ controls on guitars, effects, and amps are wide-bandwidth filters that produce broad effects. In the recording/mixing realm, the tools tend to be more subtle and complex. If your guitar’s tone knobs are butcher knives, studio EQ tools are scalpels.

Let’s sharpen our scalpels.

A typical EQ plug-in.

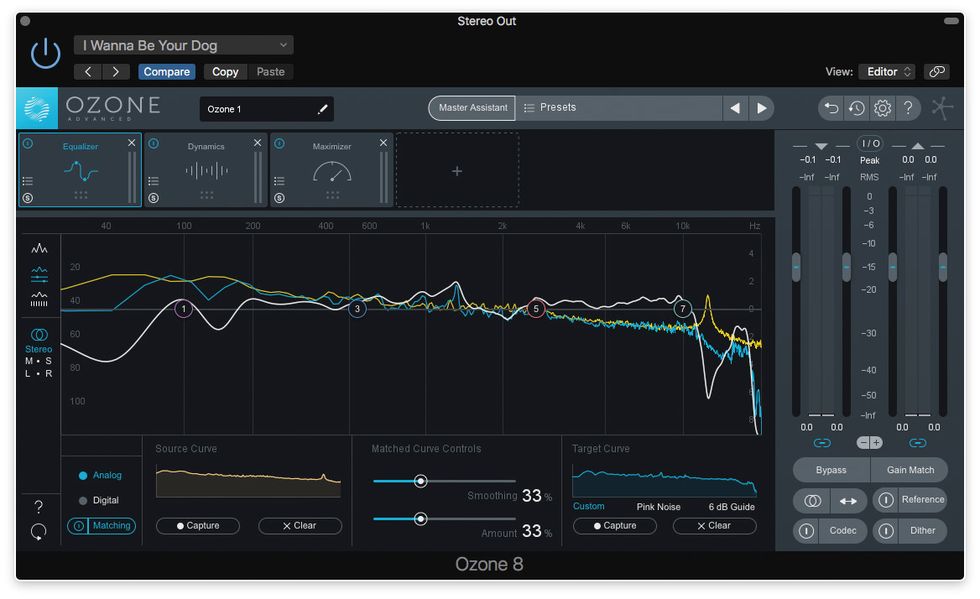

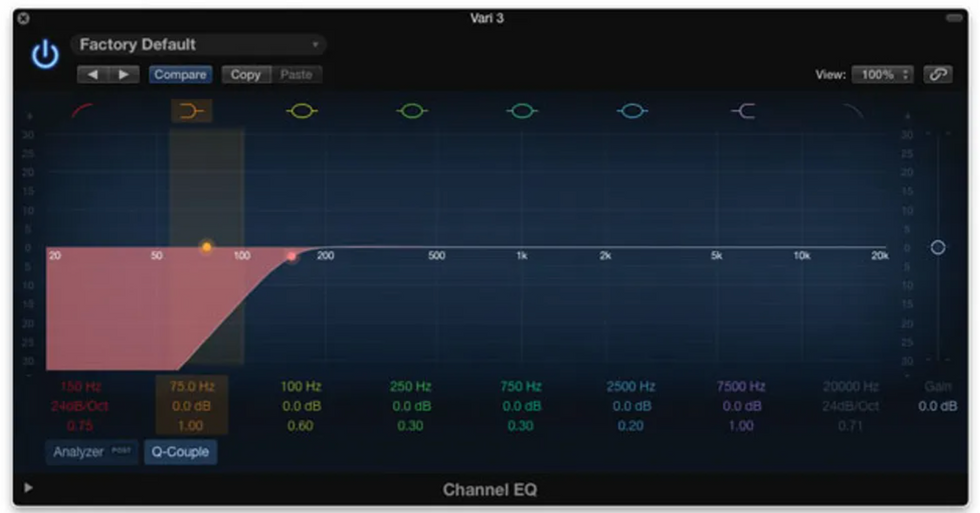

The recording guitarist can choose from a vast array of hardware and software equalizers. But for all their variation, most provide the same basic functionality. I use the EQ plug-in from Apple’s Logic Pro as my example here (Photo 1), but you’ll find similar features on many equalizers.

This particular plug-in is an 8-band EQ, which means it offers eight independently adjustable filters, though you seldom need that many. Note the three rows of numbers below each color-coded band. The top one is the active frequency in Hz. The middle is the amount of boost or cut in dB. And the lowest number represents bandwidth.

Let’s check out the effect they have on the sound of a distorted guitar track. Ex. 1 has no EQ — it’s the sound from the amp as heard by the mic.

In Ex. 2, I’ve activated the leftmost band, a high-pass filter that chops everything below a specific frequency.

Photo 2

Here, set to 150 Hz (Photo 2), it thins out the sound in a big way.

Photo 3

The rightmost band is a low-pass filter that works the opposite way. Set to cut everything above 1.1 kHz (Photo 3), it makes the guitar sound dark and dull.

Recording Guitarist: ABCs of EQ -- Audio 3 by premierguitar

Listen to Recording Guitarist: ABCs of EQ -- Audio 3 by premierguitar #np on #SoundCloudBands 2 and 7 are shelving filters. They too affect everything above or below a particular frequency, but they can boost levels as well as cut them.

Photo 4

Cranking the lows as in Photo 4 creates a rumbling, bottom-heavy sound.

Photo 5

A high-shelving filter (Photo 5) is often used to broadly brighten a guitar track.

Photo 6

The middle four bands are the most powerful. These fully parametric EQ bands can cut or boost any audible frequency at any bandwidth. Set to a narrow bandwidth (Photo 6), they can add a honking, wah-like resonance.

Photo 7

Set to a wider bandwidth (Photo 7), it brightens a much larger swath of sound.

Photo 8

Finally, I’ve combined multiple EQ bands for a fairly typical crunch-guitar EQ adjustment (Photo 8).

Recording Guitarist: ABCs of EQ -- Audio 8 by premierguitar

Listen to Recording Guitarist: ABCs of EQ -- Audio 8 by premierguitar #np on #SoundCloudWhich sounds best?

Heard in isolation, probably the first example, with no EQ. But guitar tracks seldom exist in isolation. The “right” setting always depends on the context. And that’s where we’ll pick up the thread next month, when we look at real-life EQ adjustments in real-life studio contexts.

[Updated 1/11/22]

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)