On a blustery Sunday night in New York City's Times Square, the mood is bittersweet as devoted fans flock to a special weekend screening of Purple Rain. While many here are still trying to come unstuck from the notion of a world without Prince tearing up a stage or dropping another uniquely multihued album, there's also a sizzle of expectation in the air, almost as though a full-blown concert, and not just a movie, is about to jump off.

After all, this was the film that, more than 30 years ago (in the summer of '84), established Prince, playing a character known simply as the Kid, as an explosive musical talent to be reckoned with. Maybe his acting chops didn't quite set the world on fire, but that's yet another of the saving graces of Purple Rain; as campy as the film is, the story it tells is straight-ahead, timeless, romantic, and familiar. Sacrificing himself for his art, the Kid fights through family strife, ridicule (from his rivals Morris Day and the Time), and his own demons to realize his lifelong dream. And naturally, he gets the girl in the end.

One scene in particular sends a knowing murmur through the theater crowd. The Kid is wooing his love interest, Apollonia, when he stops in front of a shop window to admire a guitar. “Do you see something you like?" she asks him. He answers only “Let's go," and the camera cuts and pans slowly over Apollonia's shoulder to reveal a white, curvy, alien-looking axe, slung upside-down (for a lefty—like Jimi Hendrix, let's say) from a black mannequin's neck. It's foreshadowing that hits you over the head, but the statement is clear: This is the Kid's totem, the staff of Moses, his ticket to the big time. And one day soon, it'll be his to play.

“For a solidbody, when it comes to shaping wood, that's about as tough as it gets. And painting it was the worst thing ever!"

“That's what a guitar is really, at least in the rock world," says Dave Rusan, the original builder of what would become known in Prince-ly lore as the Cloud guitar—one of four he made in the mid-'80s. “It's so much more than just part of a costume. It's a means of expression, power, identity, you name it. And honestly, I didn't know how it was going to be portrayed in the movie, because we didn't have any hints of a plot line or the script or anything. But when I first saw it, I remember thinking, 'Oh wow—there it is!' I was quite surprised."

At the time, Rusan lived and worked in Minneapolis doing repairs at Knut-Koupée Music, the hip Uptown store cofounded by a local guitarist named Jeff Hill. Prince started coming in when he was still in high school, and by the late '70s, after he'd signed to Warner Bros., he was a regular customer. Rusan remembers first hearing about Prince through David Z, who produced some of his early demos.

“One day David walked in with a boom box with a cassette in it, which was how you listened to stuff on the fly back then. He just came into the store and put it up on the counter and played it. After a while we went, 'God, who's this band? They're great—they sound just like Earth, Wind & Fire!' And he said, 'This is one guy. This is Prince.'"

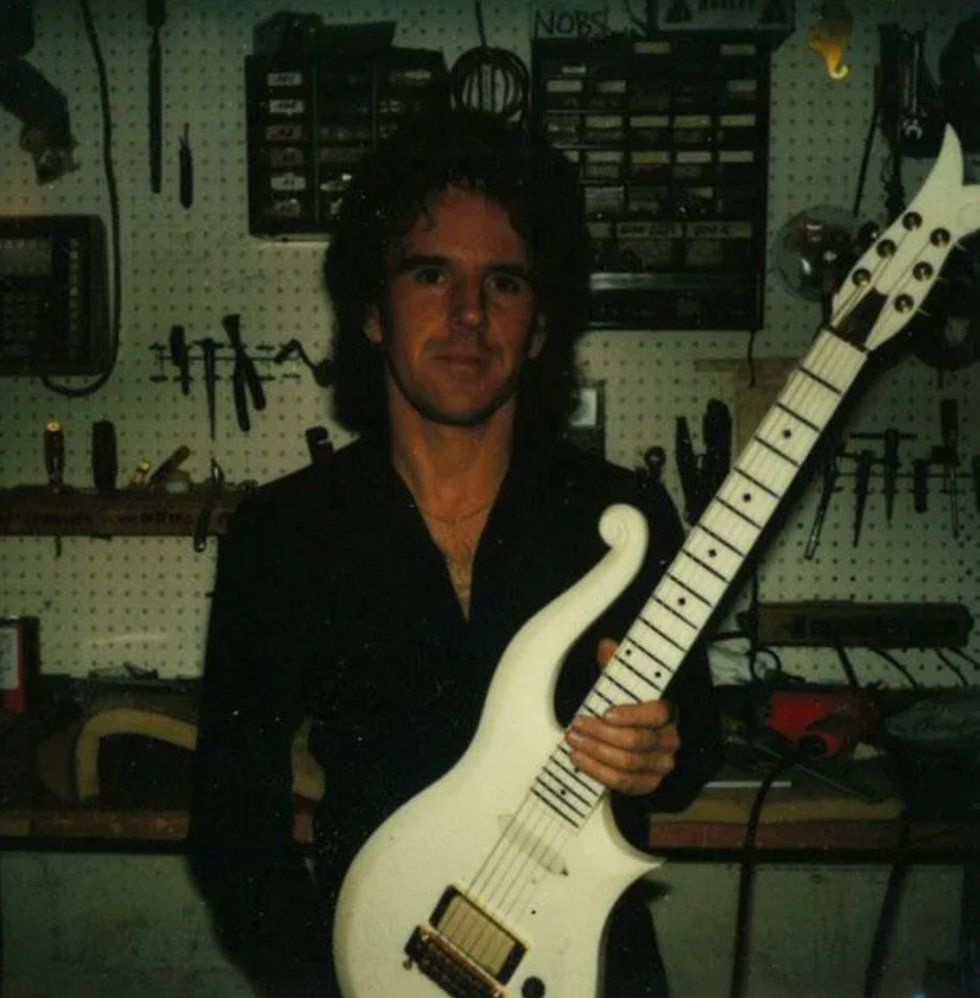

Minneapolis luthier Dave Rusan holds the very first Cloud guitar built for Prince in 1983. Rusan is standing by his bench in Knut-Koupée Music, the guitar repair shop he worked at that Prince frequented and commissioned to build a one-of-a-kind axe for the film Purple Rain.

By the middle of '83, Prince's album 1999 had put him on the map with the hits “Little Red Corvette" and “Delirious." Word started circulating that he had even bigger plans for his next project. “I'd been in London working at another shop for about nine months," Rusan recalls. “When I came back, there was Prince up at the counter. He and Jeff went into the back office and they talked a long time, and then Jeff came down and told me, 'Prince is going to make a movie. He needs a guitar, and you're going to make it.' And I was like, wow. I didn't see that coming. He'd already had some success, and had a few albums out, but not too many people made movies until they were much bigger—like Elvis, you know?"

Prince told Hill he needed a fully functioning instrument, but with an unusual design that he wanted to swipe from a bass once owned by André Cymone, Prince's childhood friend and former bass player. “We were recording his first album [For You] at the Record Plant in Sausalito," Cymone remembers. “We had a day off, so we just got in the car and drove. I spotted a shop in San Rafael, we popped in, and I saw the bass. I played it and fell in love, but I didn't have the cash at the time, so I asked Prince to buy it and he did. I'm not completely sure who the maker was—I haven't seen it since I left the band. I was pretty surprised when I saw him playing a guitar version. I'd never seen anything like that before."

Cymone goes on to say that he believes the original bass might have been made by Spector. Rusan thinks it was Sardonyx, but a search of both manufacturers turns up no images or background information. Cymone can be seen playing the bass in the music video for Prince's “Why You Wanna Treat Me So Bad." Lefty bassist Sonny T also appears to be hefting it again, years later, in the video for “My Name Is Prince." For now, these two instances seem to be the only visual proof that it ever existed. It wouldn't be the first mystery associated with Prince, who was a soft-spoken natural at keeping even his closest friends guessing about his studio secrets, let alone his true feelings and intentions.

According to curators at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, this yellow Cloud guitar was donated in 1993 from Paisley Park Enterprises through Skip Johnson, who was a production manager for Prince. The museum's records list David Rusan as the builder, along with Barry Haugen of Knut-Koupée Enterprises in Minneapolis.

Photo courtesy of the Division of Culture & the Arts, National Museum of American History, Behring Center, Smithsonian Institution

“Prince wasn't much for small talk," Rusan says. “He could certainly express himself if he felt it was necessary, but in this case he didn't all that much. So he had this bass with him in the store that day—I'd actually worked on it before—and his main requirements were just that the guitar should be in that shape, and it had to be white, and it had to have gold hardware. I think he specified he wanted EMG pickups, but compared to all the conversations you would have with somebody about a custom guitar, there wasn't anything else he wanted to talk about—the size of the neck, the frets, the playability features, or anything. He did come in once after that, and Jeff was able to get him to make a few comments, but I figured if he's not going to tell me what he wants, I'll make something I think he'll like and hope for the best."

In fact, Prince loved the guitar so much that he asked for two more. Rusan made a fourth for a contest giveaway sponsored by Warner Bros. in '85; its whereabouts are currently unknown. Later in the '90s, Washington-based luthier Andy Beech made 27 additional copies. The guitar also features prominently in Doug Henders' cover art for Prince and the Revolution's Around the World in a Day, which apparently is how the Cloud got its famous nickname. Prince's character is wearing a cloud-covered blue suit in the painting—the same suit he sports in the video for “Raspberry Beret."

These days, Rusan is still a busy and much sought-after luthier and custom specialist at his Rusan Guitarworks shop in Bloomington, just south of Minneapolis. He shares his memories openly and fondly—at one point in the very early days, he even auditioned for a spot in Prince's band—and he's still grateful for the trust Prince placed in him to make what essentially became his signature instrument for 20 years, starting with his memory-searing performance of “Purple Rain" on film—still a triumph of arena-rock theater and emotion.

“To be honest, I'd never done anything like it before," Rusan says. “I did a whole lot of repairs for a long time, but I'd never made a neck-through-body guitar or done anything involving that much carving. So I thought I'd take a shot, because I knew I'd always regret it if somebody else did it. It's amazing what you can do when you have to."

Cloud Guitar specs (per Dave Rusan):

- All hard rock maple neck-though-body construction

- 24 3/4" scale length

- 12" fretboard radius

- 14-degree headstock angle

- 5-degree neck to body angle

- EMG active pickups, powered by a 9V battery in the control cavity, with an 81 humbucker in the bridge position, SA single-coil in the neck

- Schaller M6 tuners and bridge

- Brass nut

- One master volume, master tone and selector switch, with Fender Jazz bass knobs

After 1999 came out, Prince was pretty well-known for playing his Hohner Mad Cat T-style. Did any of the specs from that figure into the making of the Cloud guitar?

I've worked on the Hohner many times—but no, because at that time I didn't see it as much. It's only been in later years. I had it in here about 10 years ago because it suffered an accident, and I had to make it look good again for TV, you know? But it really had no relationship in any way. Nothing about it—from construction style to scale length. It was a whole different thing.

So what were the basics you started with? It sounds like you had free rein to create the guitar you thought he wanted.

Well, I copied the body of that bass very carefully, and all the details of sizing it down for a guitar. I just did what I thought was best, since I wasn't able to get a lot of information from him. So I used hard rock maple and a neck-through-body with 22 frets, and the pickups were EMG active electronics. The single-coil in the neck is the SA Stratocaster model, and the one on the bridge is a model 81 humbucker like you'd put in a Les Paul. I think he specified those because they were very noise-free, and they still are. They don't lose their clarity no matter how much overdrive you put on them, and Prince would use a lot of distortion on some of his leads—the end of “Let's Go Crazy" has a lot of that. The clarity and definition comes out. They wouldn't get muddy like some of the more traditional pickups.

But I basically devised a step-by-step plan and just went about it, and Prince was plenty happy with it. I had put together Teles and carved some necks by that time, but I never made a guitar like this one. And for a solidbody, when it comes to shaping wood, that's about as tough as it gets. And painting it was the worst thing ever! The first guy who painted it had trouble because he did it in cellulose lacquer, and the clear coats tend to have a little bit of yellow in them. In the horn area, parts of it would start to get too yellow, so we had to strip it down and try it again. So it was tough. Normally on guitars, you can buff everything with a machine, but that whole thing almost had to be done by hand.

Can you describe how that first guitar sounded?

The maple made it real bright. The harder the wood, the more it reflects and enhances. It's the brightest wood you could use, and then with the neck-through body, that makes it sustain. And the EMGs have a lot of highs, so it was bright. For that funky rhythm thing that he did so well, that's mostly good.

How about the weight?

They were fairly heavy, almost Les Paul weight, because of the density of the wood. But there's not a lot to them—and everything looked much bigger on Prince! [His longtime guitar tech] Takumi Suetsugu brought in one of the later Symbol guitars [built by Jerry Auerswald] for me to work on, and I thought, “It fits in that case?" I thought it was going to be a lot bigger than it was.

So it was kind of heavy. Prince was small, but he was very fit. I went to all the rehearsals in town, because I worked on everybody else's stuff too, and a couple of times I wanted to speak to him, and they'd say, “Well, he's working out in the back room." So he could handle it. And up to a point, that extra weight increases the sustain, which makes the guitar more even-sounding, you know?

What's great is that not only is the Cloud guitar in the movie, it's also on the album.

Yeah, because some of it was recorded live right in First Avenue [where most of the stage scenes were shot]. So the guitar is actually on “Purple Rain." The other stuff, you'd have to talk to somebody like David Z or whoever engineered it. All I can tell you is that I had to make it pretty quick for the movie. I worked on just that for about 50 or 60 hours a week until it was done, you know? We painted it right in the store, too. But as far as when it was used on different albums, I'm not sure.

Once he started using it in concert, though, he wanted more of them, so I made two more. I made four all together, and the other one went to Warner Bros. That was kind of a weird thing, and I don't know what ever happened to it. They told Jeff Hill that they were going to have a contest in England to give one away. I made them all white at first, and then they were repainted. He had the peach one, and then a yellow one, but Andy Beech made a lot of the later ones.

I do know they all suffered a lot of damage. With the maple, they couldn't be any more rugged. That was part of what I thought about at the time; since it's a movie prop, I didn't want it to be delicate—and even more so in concert, because I think almost right up to the end, he had a habit of throwing his guitar to the roadie at the end of a performance. Takumi told me once it hit him in the head!

Prince's Cloud guitar reportedly got its nickname from the cover art for Prince and the Revolution's Around the World in a Day. Created by artist Doug Henders, the scene shows Prince in a blue cloud-covered suit. He wears a similar suit in the video for “Rasberry Beret."

Photo by Debra Trebitz / Frank White Photo Agency

They all had broken necks and headstocks, even being hard rock maple. I think one of them may have even bit the dust. The Smithsonian has one, which is credited as made by me, but it could've been one of the copies made by Andy Beech. Some of those were sold later at Prince's store online, too. Andy did a nice job, and then later on Schecter made some. Most of those were bolt-on necks, though. You can always tell because Takumi had input on that. He specified that the point on the headstock should be shorter so he could always identify them.

When you first see the guitar in the film, it's actually hanging off the mannequin upside-down, for a lefty—which made me think of Jimi Hendrix. Do you know if that was intentional?

It could be. I jammed with Prince once, years before, in this warehouse, and all I remember other than the band and the equipment was a big giant poster of Jimi Hendrix on the wall. So that would make some sense.

Wait, you jammed with Prince?

Actually, I tried out for his band, which was much earlier. It was around the time that For You, his first album, came out. He didn't have a touring band, and he rented an old warehouse. I think it was called Del's Tire Mart. Bands would rent out different parts of it, and at that time Prince's band was fairly complete. André Cymone was the bass player and he had Bobby Z. on drums. Matt Fink wasn't there yet, so Prince kept swapping out on other instruments. He didn't play guitar with me, but he played bass and drums and keyboards. It went on for a while—just one-chord vamping, mostly, and, in fact, I remember thinking at the time he certainly could play, and he was better at all the instruments than the other two guys, really.

How often did you see him after the really hot period he had in the '80s?

Not much. Most of the work I would do for him later, the roadies or the techs would bring them in. In a Guitar Player article around 2000, he mentioned me as the builder of the guitar, and I was surprised that he remembered me. I mean, I can't tell you all these interesting anecdotes about the two of us—it's not like Randy Rhoads and Grover Jackson, you know? He would come in and he was very shy, and my actual personal interactions with him involved very few words, if any. It was mostly done through the other people.

Looking back, would you say he's underrated as a guitarist?

Oh yeah. A lot of people have said that. He could play some jazzy lines. He didn't just shred. He could play lines that really fit and enhanced the tunes, which is the essence of being musical, rather than just being a wanker. Different tones—I don't think there was anybody that ever did the funky rhythm better than him. And then his leads, they were inventive. Everybody has influences that you can hear. Nobody starts from scratch, you know? In Stevie Ray Vaughan I could hear some Albert King and this and that, but in the end, he was himself, and Prince was like that, too.I would say he's very underrated, but I would guess that's partly because there was so much more to him. It was all there.

He played through the Mesa/Boogies in the early days, right?

Yeah. His live tone—I went to a couple of Purple Rain shows, too. He did something that seems really extravagant, although he tended to be like that. That tour was such a big deal for him, after the movie, that he rented every major venue in town and rehearsed for a few days in each of them, just to get used to moving all the stuff around, and the different acoustics and everything. It sounds kind of crazy, but it's smart if you can afford it. So his live tone was less fuzzy and more organic sounding. It was what you'd expect out of a Boogie—bigger and warmer.

I saw a rehearsal at the Minneapolis Auditorium, which was a big spot in town. It's gone now, but I watched a whole rehearsal there. It was very well organized. It wasn't like a bunch of hippies getting together. [Laughs.] It was like a theater rehearsal, and Prince directed a lot of it from the soundboard. And he was actually very supportive. I remember Wendy [Melvoin] was having some trouble with a part, and he was trying to build up her confidence that she could do it. It wasn't “What the hell's wrong with you?" It was more like, “Now Wendy, I know you can do this." And she's like a different person now. I mean, it's funny how psychological it can get in music. You can be talked out of thinking you're good, you know? I remember that time with Eric Clapton, everybody told him how good he was that he started to not believe it at all, and he felt like he couldn't play for a while.

What are your thoughts about Prince's body of work as a whole?

If I had to wrap up Prince—well, it was just the music. I'm more of a hard rock guy myself, but I always admired everything he did, and was amazed how somebody in that amount of time could take on any style and make it his own. I mean, he worked day and night, and he was so talented, but he was a virtuoso in so many other ways.

And one thing I think about him—and I don't know if this is getting off of your question—but the whole scene he created here, between his music and the visuals and his stardom and how successful he was, he just turned Minneapolis inside-out. It was really a musical backwater—you know, you could play in bars, but there were never any musicians of any note other than a couple of freaky one-hit wonders. And he turned it into the music capital. Every day was exciting. I'd go down to the rehearsals, or the store owner would be on the phone ordering a thousand purple tambourines or something. [Laughs.]

He knew how to take every aspect of stardom, from the sex, the controversy, the visuals, the color—purple was his color—and he had a guitar that didn't look like anybody else's. I don't know what he needed a manager for—I suppose mostly just for contracts. But he was totally in control of every aspect of being who he was. There was no star-maker behind him.

That's always the impression that I had of him. From a young age, he knew what he wanted to do, and he had a vision and a goal in mind, and he just pursued it.

That shows some remarkable maturity, doesn't it? For a young guy to have the discipline, and then to be able to … usually when you're that young, you don't have a vision because you don't have much of a past to draw on to make the decisions. And somehow he had all that, and it was totally self-directed. I mean, the Beatles had George Martin and Brian Epstein, and they were still really good, but he didn't have anyone like that at all. Nobody ever told him what to do, and they didn't have to because he knew what was best, and he proved it.

[Updated 1/20/22]