Moog Music’s original Moogerfooger pedals are the coffee table books of stompboxes. They delight the senses. They’re superbly crafted. But they’re big, heavy, and expensive. I own and treasure several, but they don’t typically populate pedalboards or go to gigs.

Enter the Minifoogers: five smaller-format effects at prices ranging from $149 to $219. And in addition to covering delay and modulation effects you’d probably expect from Moog, the series includes boost and drive pedals—Moog’s first gain stompboxes. The results are cool and unique.

When Downsizing is Good

There are legitimate reasons why Moogerfoogers are large and expensive. They include multitudinous knobs and switches, not to mention extensive control options—you can connect several expression pedals and adjust most parameters in real time. With relatively complex features, Moogerfoogers can feel better suited to a clean mixing desk than a scuzzy club stage.

The Minifoogers strip things down. The 5.7" x 3.25" x 2.25" enclosures are only slightly larger than most common stompboxes, and their top-mounted connectors let you pack them in tightly on a board. Gone are the Moogerfoogers’ signature wooden side panels and many of the control options—each Minifooger has just one expression pedal jack. (Expression pedals not included.) There are fewer knobs and switches as well.

Unlike Moogerfoogers, Minifoogers can run on batteries as well as standard 9-volt power. The enclosures feel solid. The interior layouts are nice and clean, with board-mounted jacks and pots, SMD components, and tidily routed ribbon connector. The Minifoogers’ uniform styling probably won’t turn heads. But if your pedalboard looks like a drunken clown barfed on it, you may welcome some basic-black sobriety.

Let’s listen in alphabetical order (by clicking the next page) or choose your own adventure:

Minifooger Boost

Minifooger Delay

Minifooger Drive

Minifooger Ring Modulator

Minifooger Trem

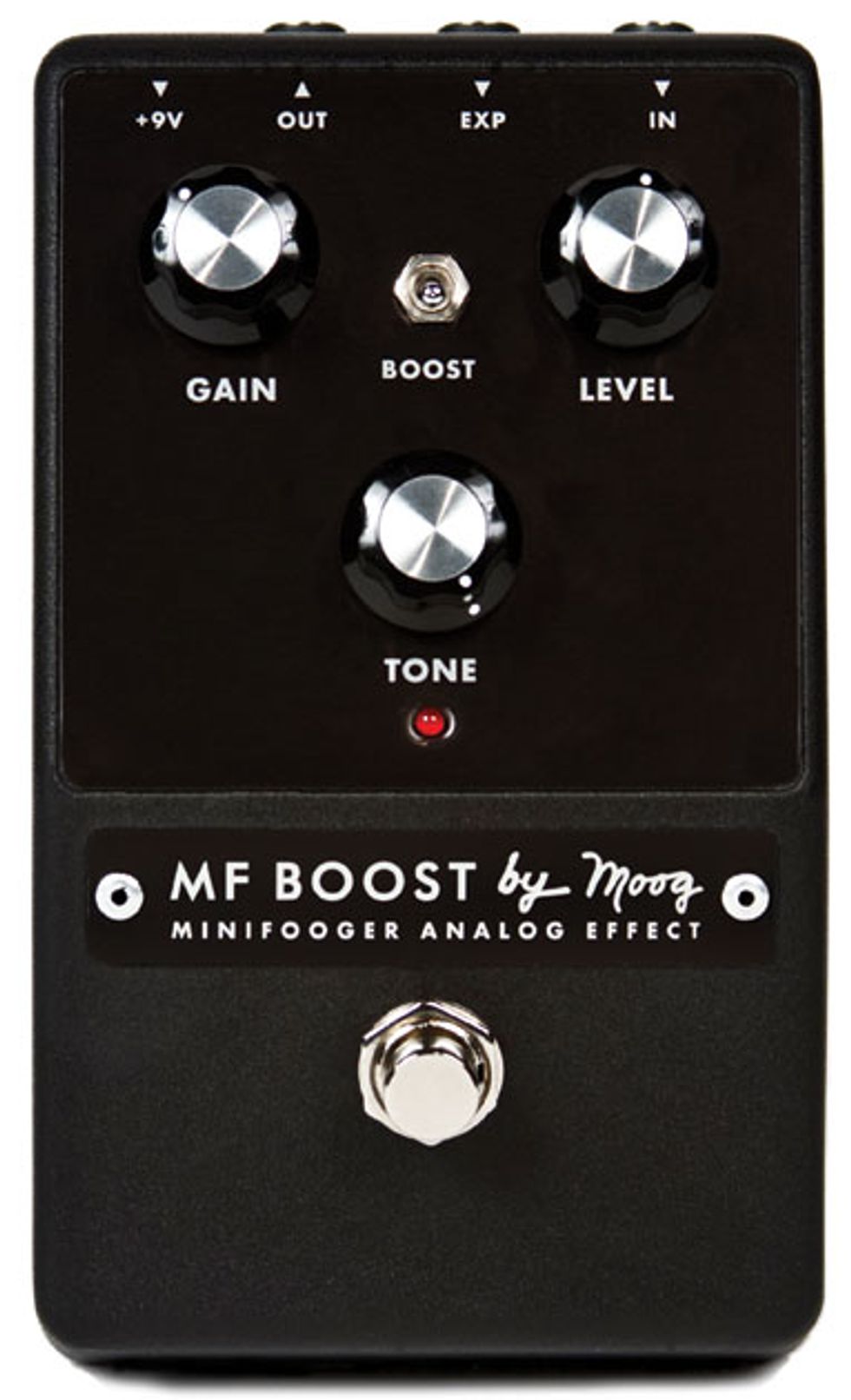

MF Boost

Moog’s first boost pedal offers something you don’t always encounter in a boost pedal: subtlety.

Actually, the MF Boost houses two separate gain circuits, selectable via toggle: VCA mode provides hi-fi, crispy-clean boost. There’s little coloration—just a feeling of airier highs, firmer lows, and increased headroom. It doesn’t sound precisely like, say, clean mode on a Klon Centaur or a Z. Vex Super Hard On, but it’s a similar “low dose of steroids” effect that flatters many guitars, especially ones with old or old-style pickups.

Ratings

Pros:

Excellent boosted tones, subtle and musical. Gain control via expression pedal (not included).

Cons:

Possibly too subtle for some players.

Tones:

Ease of Use:

Build/Design:

Value:

Street:

$149

Moog MF Boost

moogmusic.com

Toggling to OTA mode summons a slightly louder and “furrier” flavor of gain. Both modes, though, are relatively restrained. VCA mode offers +6 dB, and OTA mode doubles that. Connecting an expression offers six additional decibels in either mode. That way, wherever you’ve set the MF Boost’s gain control becomes the minimum controller pedal level, with more boost available as you advance the treadle. It’s an ingenious arrangement that lets you fine-tune your gain range, making it easy to, say, pedal between rhythm and solo levels. The only downside of the scheme is that you must connect a controller pedal to wring that last six decibels out of the MF Boost.

This may or may not be an issue, since the focus here is on the subtler end of the boost spectrum. This pedal doesn’t attempt to bludgeon your amp like many boost circuits do. It’s more about artful fattening and burnishing. Among other things, the MF Boost can make you sound as if you’re playing louder than you are, mimicking a cranked amp’s compression. It’s a great tool if you need to practice or record more quietly than you’d like.

A level control lets you trim the output after driving the gain circuit. Again, subtlety prevails: Lowering it peels off only modest amounts of level. This makes perfect sense, given the MF Boost’s relatively restrained output and the fact that you need to slap the amp with force for the best results.

The tone control is a simple post-boost low-pass filter. As such, it doesn’t alter the boost character much—it just nixes highs. But it’s perfectly voiced for taming nasty top-end. I quickly settled into an intuitive workflow: Push the gain till the texture feels right, then lower the tone till any nasty treble frequencies vanish. It worked like a charm on my vintage Strat’s bridge pickup: Cranking the gain fattened the potentially weedy sound, but added a nasty edge. Adjusting the tone control removed the nasty, leaving just the awesome.

Verdict

With its relatively modest output, the MF Boost is more of a tone conditioner than a tone changer. It can fatten, focus, and brighten without screwing up what you dig about your tones. The ability to control gain via expression pedal is unusual and potentially useful. The price is right at $149. Whoever voiced this pedal has good taste and good ears.

Let’s listen in alphabetical order (by clicking the next page) or choose your own adventure:

Minifooger Delay

Minifooger Drive

Minifooger Ring Modulator

Minifooger Trem

MF Delay

Not long ago you had to cough up the cabbage for a good analog delay, thanks to the scarcity of bucket-brigade chips. But now that the chips are back in production, we’ve been flooded—heh—with warm analog wetness. And man, the MF Delay is a stellar example. It’s a great-sounding delay with vibey tones and several remarkable features.

Ratings

Pros:

Fab-sounding bucket-brigade delay. Uncommonly powerful for a mid-priced analog delay stompbox.

Cons:

None.

Tones:

Ease of Use:

Build/Design:

Value:

Street:

$219

Moog MF Delay

moogmusic.com

The MF Delay is analog in your face. The wet signal is dark, noisy, and distorted—exactly the qualities analog delay fiends crave. The initial echo is bright enough for snappy rockabilly tones when feedback is set near minimum. But as it cycles around, it quickly crumbles into darker, noisier territory. This is a feature, not a bug—it’s what makes the echoes sit so neatly behind the dry sound. You can slather on more effect hear than you could with a digital model.

With its four bucket-brigade chips, the $219 MF Delay provides 700ms of delay time—that’s long for an analog model, and nearly as much as the $700 Moogerfooger MF-104D.

I compared the MF Delay’s tone to my Moogerfooger MF-104SD, a limited-edition version from 2005. The 104SD has an even darker sound, and more delay time. On the less expensive MF Delay, the contrast is stronger between the initial cleaner delays and the increasingly distorted repeats. I actually prefer the tone of the newer model.

Naturally, the MF Delay omits some features found on the current Moogerfooger MF-104M delay. There’s no delay modulation. You can’t inject external sound sources into the delay line. There’s no tap tempo or master output level.

Yet enough advanced features remain to distinguish the $219 MF Delay from many rival analog delays. Again, there’s real-time control via expression pedal (not included), and here, you can assign it to one of two possible functions via an internal board-mounted toggle. With the switch set to control delay time, the pedal conjures eerie whoops and smears. Or flick the switch to “feedback” to provide tasteful dub-style touches—or self-oscillating mayhem. Also, you can dial in 100% wet sounds, which means that even though the MF Delay lacks the independent dry and wet output of the Moogerfooger delay, you can still kill the dry sound when inserting the pedal into an amp’s effect loop.

The coolest special feature may be the drive control. Much of the character of vintage echo units comes from the ability to shape tone by hitting the input at various levels—so much so that many guitarists are purchasing non-delay pedals specifically designed to imitate the distorted boost provided by tape-echo input sections. With its 22 dB of gain, the MF Delay actually gets significantly louder than the MF Boost, and the distorted sounds are smooth and attractive. (The drive control affects both the wet and dry signals.) I can totally imagine cranking the gain, dialing in a dry mix, and using this solely as a boost pedal. There are no tone controls, but the default color sounded cool with both humbuckers and single-coils.

Verdict

Great-sounding delay. Great-sounding overdrive. Great real-time control via expression pedal (not included). Just plain great.

Let’s listen in alphabetical order (by clicking the next page) or choose your own adventure:

Minifooger Boost

Minifooger Drive

Minifooger Ring Modulator

Minifooger Trem

MF Drive Like the MF Boost pedal covered above, the $179 MF Drive offers a cool and uniquely Moog take on guitar distortion. At its core, this is an OTA-based overdrive that generates fat, naturalistic crunch. As you advance the gain, the signal compresses and bleeds highs in an impressive simulation of tube amp distortion. A toggle selects between high and low input levels, accommodating pickups of varied output.

Ratings

Pros:

Many cool distortion shades via filtering. Control filter frequency via expression pedal (not included).

Cons:

Too tweaky and complex for some players?

Tones:

Ease of Use:

Build/Design:

Value:

Street:

$179

Moog MF Boost

moogmusic.com

But it’s also a filter pedal—and one that interacts with the distortion circuit in cool and useful ways. Make that two filters: a multifaceted tone control and a resonant Moog ladder filter.

First, the tone control: In the lowest part of its range, it filters highs, with a dark, bass-heavy sound in the fully counterclockwise position. But as it nears the center of its range, it cuts varying amounts of midrange (at 800 Hz). As it’s moved further to the right, it peels off lows, producing shrieking treble-boosted tones at its maximum setting. Depending on its position, the control can nudge your amp toward fat tweedy sounds, scooped blackface colors, or mid-forward, vaguely British tones. That’s a lot of sounds from one little tone control.

The real fun starts when you add the resonant filter. With the peak toggle engaged, the filter adds 15 dB of gain at whatever frequency you park the filter knob. Alternately, you can use an expression pedal (not included) to control the filter-frequency, wah-style.

I say “wah style” because the character of the filtering differs from that of the leading wahs. You can definitely obtain dramatic filter effects, but don’t expect to plug in a foot controller at whip out a creditable version of “Voodoo Chile” or “Theme from Shaft.” It’s not that particular flavor, but something subtler.

Sweeping the filter knob lets you highlight particular parts of a sound’s spectrum, be it a nasal resonance, or a hearty thump evocative of closed-back cabinets. Again, this isn’t modeling per se, but it’s a way to reinvent tones. Depending on how you position the interactive gain, tone, and filter knobs, you can create the impression of varying body types, pickups, and amps. You have to fiddle around to get there, though—the MF Drive will probably appeal more to tweakers than plug-in-and-go types.

The MF Drive would be particularly useful for pinpointing an ideal frequency niche for overdubbed guitars. In this regard it’s similar to some of the new drive/filter pedals inspired by the 1980s Systech Harmonic Generator, such as a the Spontaneous Audio Devices Son of Kong and Totally Wycked Audio’s Triskelion. The MF Drive isn’t as extreme as those devices—it lacks their adjustable Q (filter bandwidth) and stronger filter intensity, so it can’t mimic their violent rumbles and shrieks. But it provides a remarkable array of options for a mid-priced overdrive. Another Tube Screamer clone, this ain’t.

Verdict

The versatile and imaginative MF Drive strikes a compromise between conventional overdrives and over-the-top “dirty filters” of the Systech Harmonic Energizer ilk. Its complexly interactive controls can be tricky to master, but they reward the patient tweaker with cool and unconventional overdrive colors.

Let’s listen in alphabetical order (by clicking the next page) or choose your own adventure:

Minifooger Boost

Minifooger Delay

Minifooger Ring Modulator

Minifooger Trem

MF RING

Has any guitar writer ever discussed ring modulation without noting that it’s not a sound for all tastes?

For the uninitiated: Unlike other modulation effects, wherein the modulation is produced by waveforms so low you can’t hear them (hence the term LFO, for low-frequency oscillator), ring mods use modulating pitches high enough to hear. Applying them to your signal unleashes sonic anarchy: alien bells, foul-mouthed robots, clangorous swoops and glides. Any of these tones will get you banned for life from your local Tuesday night blues jam.

Ratings

Pros:

Excellent analog ring-mod sounds at a fair price.

Cons:

Haters gonna hate.

Tones:

Ease of Use:

Build/Design:

Value:

Street:

$159

Moog MF Boost

moogmusic.com

Sound like fun? If so, you may be a ring mod pervert. And despite what the haters say, you can find uses for these clanging noises, especially when they’re mixed subtly with conventional guitar tones.

The MF Ring, a $159 spinoff from Moog’s $299 MF-102 Ring Modulator, omits some of the larger pedal’s features. (I won’t say it omits “bells and whistles,” because it does bell and whistle sounds just fine.) While the MF-102 lets you route a controller pedal to any parameter, on the MF Ring control is locked to modulation frequency—definitely the most dramatic option. Also absent: a choice of modulation waveforms, a drive control, and a toggle to shift between higher and lower frequency ranges. And with its minimum oscillation frequency of 90Hz, the MF Ring doesn’t allow you to slow down the modulation sufficiently for tremolo sounds. (On an MF-102, dialing in frequencies under 10Hz or so yields gorgeous, shimmering tremolo—one of the pedal’s great “secret sounds.”)

But make no mistake, the MF Ring can be just as alienating as its Moogerfooger uncle. And by alienating, I mean both “bumming out conservative ears” and “making you sound like an alien.”

A wet/dry mix control and a treble-nixing tone control are essential for dialing back the intensity of the effect. Ring modulation can (and usually does) introduce wild high-frequency content well above the usual guitar range. Taming that can be the difference between the tone that gets you hired and the one that gets you fired. Overall sound quality is comparable to that of the MF-102—there are just fewer options.

As on the MF Boost, connecting an expression pedal (not included) expands the range of the effect, here widening the sweep of the modulation frequency. Again, it’s a clever way to players determine the range of their sweeps, but bear in mind that you must use a controller to access the MF Ring’s full repertoire.

VerdictThe MF Ring performs as advertised. The price is fair. It’s also one of your only options for a dedicated, true analog ring modulator. On the other hand, digital ring modulation, available on many multi-effectors, has all the—um—emotive power of analog. Whether the MF Ring warrants a plot of land on your pedalboard, I can’t say. Consult your inner pervert.

Let’s listen in alphabetical order (by clicking the next page) or choose your own adventure:

Minifooger Boost

Minifooger Delay

Minifooger Drive

Minifooger Trem

MF Trem

Moog’s $179 MF Trem is a gorgeous little analog tremolo with cool features you may not have encountered in a trem. But once you try them, you may get hooked.

The pedal’s shape control fades between three trem types: smooth rise and fall, sharp rise/smooth fall, and smooth rise/sharp fall. Variations include everything from corpulent, optical-sounding trem to slappy/choppy flickering à la Vox Repeat Percussion. It’s an easy, intuitive way to access a lot of trem colors.

Ratings

Pros:

Lovely trem tones. Lots of variation. Pragmatic controls. Real-time speed control via expression pedal (not included).

Cons:

No tap-tempo.

Tones:

Ease of Use:

Build/Design:

Value:

Street:

$179

Moog MF Boost

moogmusic.com

The rate control has a generous range: At maximum, you get a throaty purr bordering on ring modulation. The depth control works as expected, though it interacts with the tone controls in not-so-expected ways.

Yes, the MF Trem has a tone control, a simple low-pass filter that effects only the wet signal. But since the depth control is really just a wet/dry blend, the tone control’s effect varies with the depth amount. At low tone/high depth settings, you encounter cool and subtle phasing effects. The pedal never sounds quite like a Uni-Vibe, Leslie cab, or brownface Fender vibrato circuit—there’s no actual pitch modulation here. But the MF Trem captures some of the rich, phasy goodness of those devices. And of course, the effect changes dramatically once you alter the shape setting.

Such interactivity may sound daunting, yet it’s easy to dial in tones. One good method is to set the rate and depth like you normally would, then just jiggle the shape and tone knobs till the tone feels right in context. Sounds stupid, but it works.

There’s no tap-tempo function, however. Nor is there a level control. (Trem effects sometimes benefit from a modest level boost, depending on the musical context.) But here, brighter tone settings accomplish the task.

Attaching an expression pedal (not included) lets you pilot the trem speed by foot. Ever tried this? If not, you’re missing out! It’s a lovely expressive effect, especially when you alter the rate in the pauses between musical phrases. It’s like a less gooey take on the rotating Leslie sound, and a grossly underexploited effect.

Verdict

The MF Trem offers a fine palette of lush, tactile tremolo tones. It strikes an appealing balance between basic two-knob trem circuits and the mad scientist boxes that let you tweak every parameter. There are many fine tones here, and it’s easy to dial them in.

Let’s listen in alphabetical order (by clicking the next page) or choose your own adventure:

Minifooger Boost

Minifooger Delay

Minifooger Drive

Minifooger Ring Modulator

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)