A gorgeous ’54 Gibson Les Paul came through our shop

for show-and-tell one day. I must

admit it was an exquisite-looking,

mint-condition guitar, and if it

weren’t for the one volume pot

that had been replaced, it would

still be in 100-percent original

condition. There are people who

wouldn’t have a big issue with

this, yet others would react to the

replaced pot and think, “If the

volume pot has been changed,

what else is not straight on the

guitar?” This is just one of those

concerns and quirks of doing biz

in the world of vintage guitars.

Many very qualified and

well-educated collectors and

dealers say that in today’s vintage

guitar market, you have to

accept that things get changed

along the way when it comes to

worn-out electronic parts. It is

just a reality, like a Stradivarius

violin needing a neck rebuild,

fingerboard level, or top or back

removal over time.

That’s all true, but when

it comes to manufacturing

potentiometers, most of today’s

materials are subpar compared to

the virtually unbreakable materials

of yesteryear. This is certainly

true when it comes to guitar electronics.

Have you ever noticed

how often you might replace the

pots on your main guitar from

the ’70s or ’80s, or how your

newer guitar can lie in its case

for a few months and when you

go to play it, the volume pots are

scratchy and won’t even clean up

with proper cleaner?

Vintage guitars from the

’50s and ’60s have some of the

best-built potentiometers ever.

These pots featured heavy carbon-resistance

material instead of the

inferior silk-screening currently

used by many of today’s makers.

These old-school materials rarely

wear out. If there’s a problem, it’s

usually caused by corrosion on the

wipers or brushes, solder bleed, or

tainted substances that find their

way onto the resistive material. For

the most part, this is all restorable.

When the original pot

was removed from the

show-and-tell ’54 Les Paul,

fortunately the owner placed it

inside the case’s compartment.

I couldn’t have been more

pleased to find this, and I was

certainly up for a challenge in

restoring this 1954 pot.

IRC (International Resistive

Company) pots were used on

many Gibson Les Pauls. Today,

IRC provides one of the industry’s

most comprehensive ranges

of innovative resistor solutions

for automotive, computer, communications,

medical, industrial,

military, and instrumentation

markets worldwide.

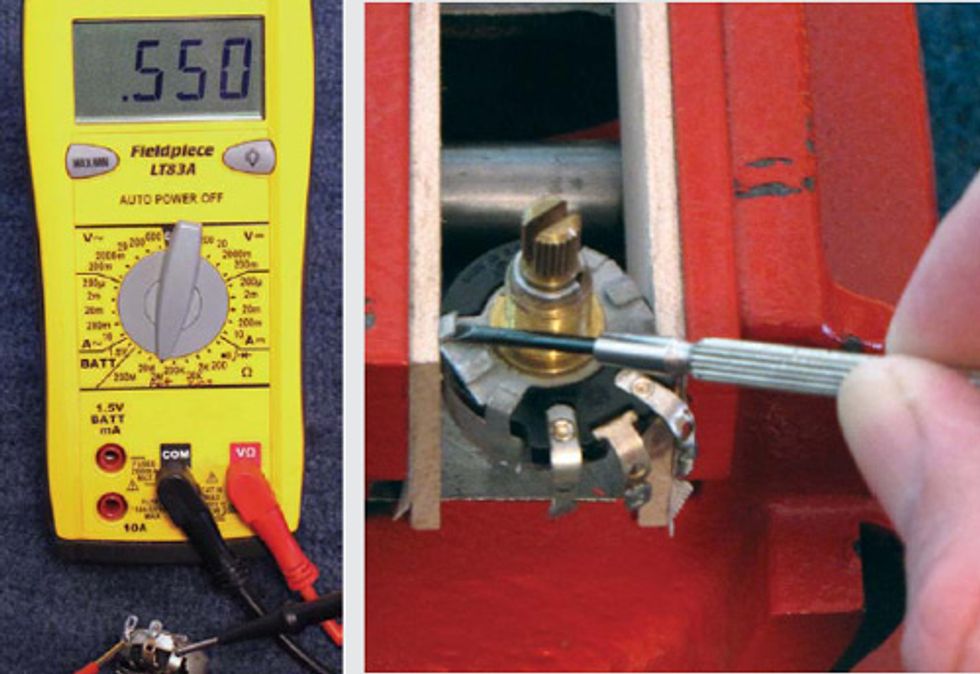

Left: Measuring the potentiometer’s resistance with a digital multimeter.

Right: Carefully prying open the pot’s chassis-support tabs.

I began restoring this vintage IRC pot by using my portable digital multimeter to read the pot’s resistance in ohms (Photo 1). The brass shaft section of the pot was locked in open position, and it would not rotate. In open position, the resistance read 550 kΩ— despite the fact that the pot’s chassis was stamped 500 kΩ. On the side, another group of numbers indicates the year of manufacture (you’ll need a source-date code system to interpret them).

Consider this: In pursuing ultimate tone, if we’re really stuck on the accuracy of a 500 kΩ pot, we have to be aware of some serious variability going on here. The IRC pot I was restoring reads 550, yet I can buy a bag of modern pots and most of those will read under 500 kΩ, at times even as low as 450 kΩ. That’s a potential 100 kΩ difference between the two. Wow—isn’t that an eye-opener? It’s a good idea to always use a meter and select your pots accordingly.

My next step was to use an angle vise (which works well because it has some girth) to hold the pot as I tried to manipulate its shaft (Photo 2). Unfortunately, the pot’s durable brass shaft wouldn’t budge loose—it was as if it was once glued into position. This meant it was time to investigate inside.

Notice how I attached two maple strips to the vise jaws to support the pot and protect it from scratches or damage. I used a mini screwdriver that’s slightly narrower than the chassis- support tabs to bend them open. The size is important, because later when everything is reassembled, any micro pressure marks will be hidden under those four tabs. This creates an invisible restoration.

We’ll conclude our pot-restoration project next month and list the tools you need for this work, so be sure to swing by for the second installment.

John Brown is the

inventor of the Fretted/Less

bass. He owns and operates

Brown’s Guitar Factory,

a guitar manufacturing,

repair, and restoration facility

staffed by a team of talented

luthiers. His guitar-tool and accessory designs

are used by builders all over the world. Visit

brownsguitarfactory.com or email John at

info@brownsguitarfactory.com.

John Brown is the

inventor of the Fretted/Less

bass. He owns and operates

Brown’s Guitar Factory,

a guitar manufacturing,

repair, and restoration facility

staffed by a team of talented

luthiers. His guitar-tool and accessory designs

are used by builders all over the world. Visit

brownsguitarfactory.com or email John at

info@brownsguitarfactory.com.