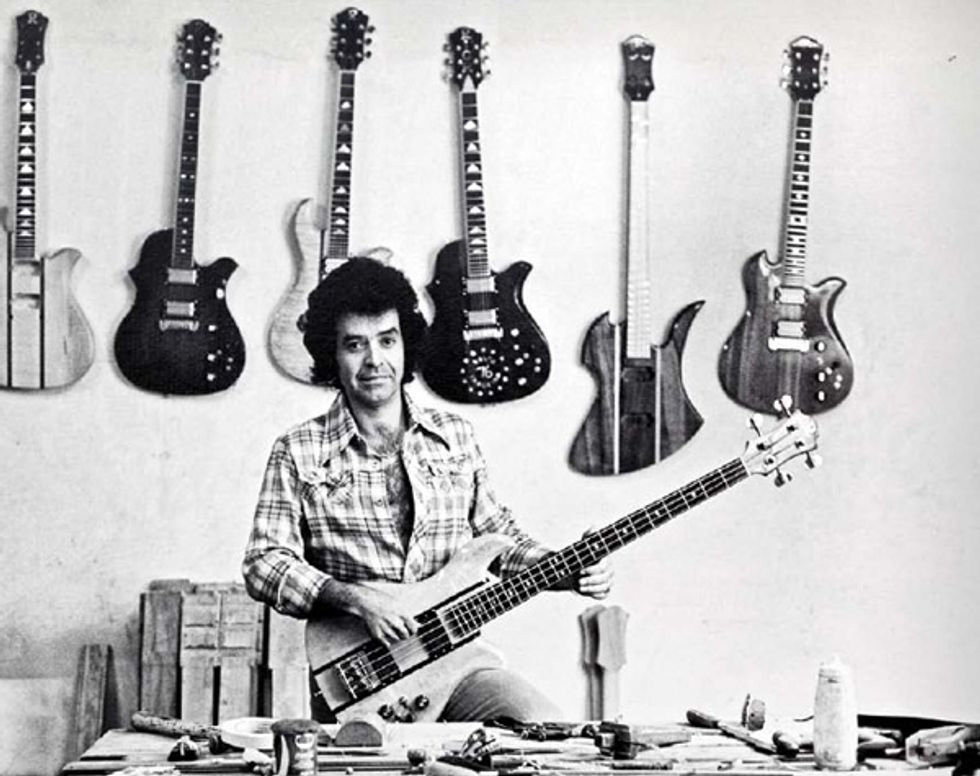

Bernie Rico Sr. with an early Eagle bass at his L.A. fabrication shop on Valley Boulevard circa 1977. A Mockingbird bass and various double-cutaway Eagle and single-cutaway Seagull 6-strings hang behind him.

Photo by Andy Caulfield

During the ’80s, the wild shapes of B.C. Rich guitars proved to be the perfect match for the over-the-top theatrics of the burgeoning heavy metal craze. The image of W.A.S.P.’s Blackie Lawless dripping in blood while clutching a B.C. Rich Widow in one hand and a skull in the other was just one of many that catapulted B.C. Rich to being the No. 1 guitar company as metal came to rule the airwaves. “The company grossed around $175,000 when I started working there and, with the [introduction of the] NJ Series, it was up to about $10,000,000 by the time I left,” says Mal Stich, who was vice president of B.C. Rich during its ascent. For this historical retrospective, Stich gave Premier Guitar a first-hand account of the company’s milestones. Additional information has been provided by Neal Moser and Lorne Peakman.

Although B.C. Rich has crafted an identity as a metal guitar company, it actually started as one of the first boutique electric-guitar makers—it was among the first to introduce neck-through-body 24-fret guitars and heelless neck joints. Many respected artists outside the metal community, including studio great Carlos Alomar (David Bowie), pop meister Neil Giraldo (Pat Benatar), and jazz guitarist Robert Conti were proponents of B.C. Rich guitars.

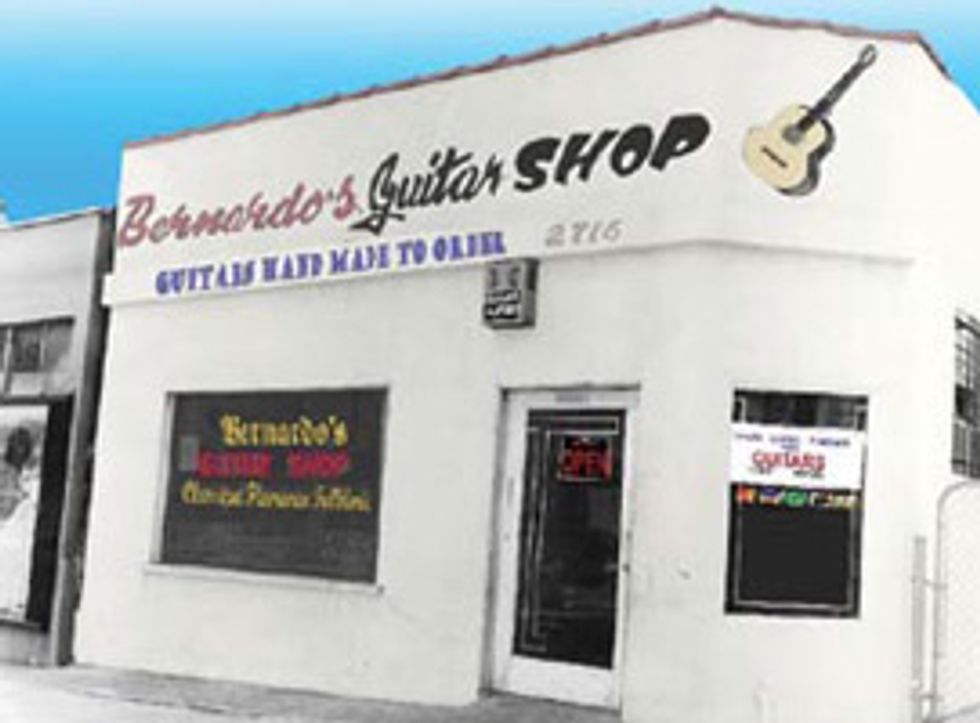

LEFT: An early photo of Bernardo’s Guitar Shop located at 2716 Brooklyn Avenue in Los Angeles.

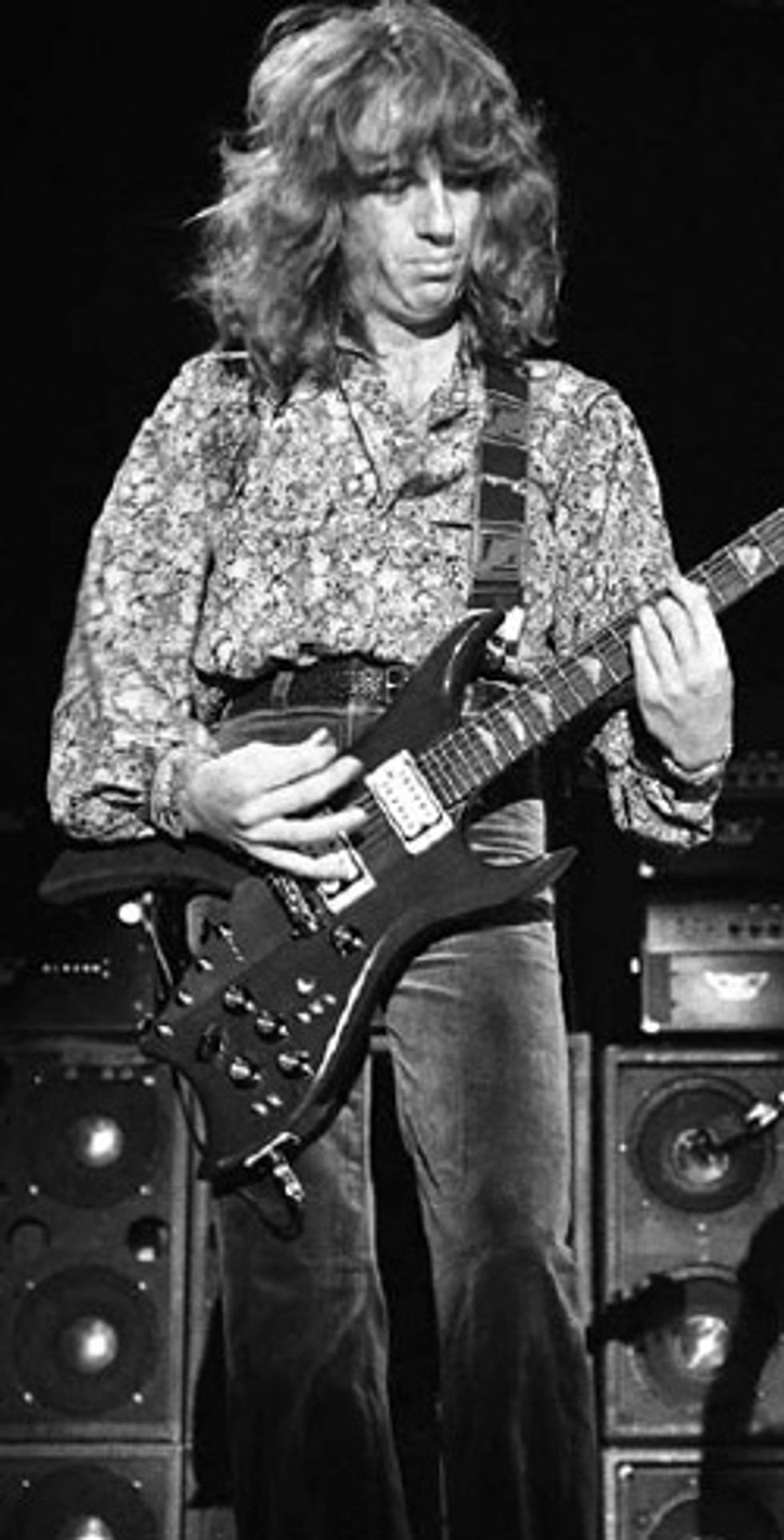

RIGHT: Mal Stich with a custom B.C. Rich circa 1978. Photo by Andy Caulfield

Where It All Began

B.C. Rich’s origin can be traced to Bernardo’s Guitar Shop at 2716 Brooklyn Avenue, in Los Angeles. In the mid ’50s, Bernado Mason Rico purchased the store from the Candelas guitar shop and opened his namesake store. He didn’t work on the guitars himself—he chose to focus on day-to-day operations—but instead hired luthiers from Paracho, Mexico, which is widely regarded as the guitar capital of that country. Rico helped many of these luthiers gain residence and naturalization as citizens of the United States. Rico’s son Bernardo “Bernie” Chavez Rico, an accomplished flamenco guitarist, did become involved with the guitar making, however.

Father and son brought bodies in from Mexico, had them painted and assembled at the shop for mariachi, classical, and folk musicians. By the early ’60s, folk music had become popular and folk artists started bringing in their acoustic steel-string guitars to the shop for repairs. Word spread, and throngs of musicians like Barry McGuire and David Lindley started bringing in Martins and Gibsons for work and daring modifications, such as disassembling a Martin D-18 and putting in a 12-string neck.

The folk boom led to the shop’s production of steel-string acoustics, which featured Brazilian rosewood back and sides, Sitka spruce tops, and Honduran mahogany necks with Gaboon ebony fingerboards. Although these early guitars were reportedly rated higher than new Martins at the time, they had some minor issues. Because they didn’t have an adjustable truss rod, the guitars were often brought in later to have the fretboard removed and a truss rod installed. They also had very thin spruce tops that sounded nice but were known to crack and move from 1/16" to 1/8" into the soundhole if too much string tension caused the neck to fold into the body. These issues were quickly addressed without question, and problem instruments were repaired or replaced even many years past the one-year warranty.

In 1968, Bernie made his first electric solidbody using a Fender neck. This led to his first attempts at guitar production in the form of about ten Les Paul-shaped guitars and basses modeled after the Gibson EB-3. Around 1972, Bernie and an employee named Bob Hall started developing a model they called the Seagull (which has no connection to the Godin Guitars acoustic brand). It was the company’s first production electric guitar, and it came to market in 1974. Up to that time, the store’s phone greeting was “Bernardo’s Guitar Shop.” One day, Stich answered the phone with, “B.C. Rich,” and some think that’s the moment the company name changed and it became a full-fledged guitar manufacturer with a mission.

“B.C. Rich’s intention was to make a production-line custom guitar with high quality and craftsmanship that was very expensive for the day,” says Stich. “In 1977, they were $999 retail—and you were paying more than retail if you could actually find one.”

Although, B.C. Rich was often referred to as a custom shop at the time, it wasn’t custom in the conventional sense of the word. “The guitars were handcrafted, but they were still production guitars. People might request special inlays or maybe Bartolini Hi-A pickups instead of DiMarzios, but basically it was a production-line guitar,” explains Stich. The company had facilities in both California and Tijuana, Mexico. All the workers were from Mexico, and both shops freely interchanged parts. For the electric guitars, Bernie would send wood, fretboards, frets, inlays, glues, and other materials over to Mexico, and then drive down once a month to pick up the assembled guitars, which were then painted and finally assembled in L.A. The steel-string acoustics, however, were made right there in L.A.

B.C. Rich luthier Juan Hernandez (left) shaping a body with a knife similar to

the ones at right. Photo by Andy Caulfield

Handmade—All the Way Down to the Tools

When Stich says early B.C. Riches were handmade, he means it in the truest sense of the phrase. He recalls that there were no machines in sight inside the shop—only band saws, belt sanders, block planes, spoke shaves, files, and special guitar knives that the luthiers made themselves out of highly carbonized metal. “The guys would literally go out and buy a metal slab that was probably a quarter inch thick, and they would cut it, shape it, sharpen it, and make a handle for it—usually out of mahogany. People would walk in and go, ‘Where’s your machinery?’ and we’d go, ‘Sittin’ right there,’ and point at a knife. Then they’d go into the paint shop and guys would be water-sanding, finishing coats, and buffing by hand. When they cut the blanks, the sides would be glued on and wrapped with cord like in the old days, when they made violins and wrapped them with cords in France in the 1500s. They would tap shims between the cord and the wood to make it as tight as possible for the glue joints, which were always superb. The guitars would go through a process of being marked out with a pencil and a template of the shape of the guitar—we had aluminum templates and later plastic—and then they would do a cutout on a band saw. From there, the necks would be handcarved using what I call a ‘Mexican guitar maker’s knife,’ and they just hacked the [expletive] out of it. It would start out with a hammer and a chisel—bam, bam, bam—making the neck. Then they would go to the knife, and finally to a spoke shave. These guys could knock out a neck in about 20 minutes.”

|

After the body and neck were completed, the last stop was the assembly shop—where everything was hardwired. “The parts—the Varitone, the preamp circuitry, etc.—were made by hand,” says Stich. “We would go to the electronics store and buy all the parts we needed, and they would cut up the PCB boards. It was really labor intensive.”

Intricate Circuitry

Noted luthier Neal Moser, who had developed a reputation as the go-to guy for hot-rodding guitar electronics, joined the company in 1974. Over the initial dinner meeting at Bernie’s house, Moser sketched out the circuitry and layout for a new design on a piece of cardboard. He soon went to work for B.C. Rich as an independent contractor. His dinner-table design—which consisted of master volume and tone controls, a built-in preamp, a 6-position Varitone, and coil taps—was implemented on the production Seagull guitar.

B.C. Rich’s electric offerings were originally equipped with Guild pickups, but the company later switched to DiMarzios, which Stich says, “added a whole different reality to the guitars. The Guilds had this ’50s or ’60s sound, whereas the DiMarzios had a new sound to them. They also worked better with Moser’s circuitry.”

Wilder and Wilder Shapes

B.C. Rich guitar bodies always pushed the envelope of guitar design, and as the years progressed, the shapes got even more extreme. The Seagull’s toilet-seat-inspired shape was daring for the time, but fairly conservative in hindsight. And though it was well received, the protruding point on the upper body was uncomfortable for some players because it poked into your torso at certain playing angles. This led to the creation of the Eagle, which had a more conventional Strat-like shape, but with the Seagull’s treble-side cutaway. Another version of the Seagull that jettisoned the sharp point was also later produced. In 1975, the company introduced its first radically shaped guitar, the Mockingbird, which was inspired by a shape drawn by Johnny “Go Go” Kallas and named by Moser.

In 1977, while Bernie was in Japan, Moser went into the woodshop one day and crafted the company’s edgiest design to date—the 10-string Bich. According to Stich, when Bernie returned to the shop and saw the new project, he got upset and yelled “You guys don’t design guitars without me!” The model’s name stems from a trip Moser and his wife made to the county fair. “They noticed some girls wearing charms on their necklaces that read ‘Rich Bitch.’ They agreed that would be an ideal name,” recalls Stich. “Of course, the ‘T’ was dropped.”

This five-piece, koa-bodied 1979 Mockingbird features an intonatable Leo Quan Badass bridge and multiple knobs and toggles for the built-in preamp and its phasing, tone, and series/parallel operation options.

This gorgeously quilted 1981 10-string Bich features two preamps controlled by six knobs (Master Volume, Master Tone, neck-pickup volume, a 6-position Varitone, and Volume knobs for both preamps) and six toggles that govern pickup selection and series/parallel operation, phasing, and activation of the preamps. The guitar has unison strings for the D and G strings, and octaves for the B and high E.

That model led to the 6-string Bich and the Son of a Rich, an American-made economy version with a bolt-on neck and bodies machine-made by Wayne Charvel. Initially, there was some concern that dealers would reject the guitar based on its risqué name, but after some dealers from Utah—the most conservative state in the Union—gave it the green light, the name stuck.

Introduced in 1981, the company’s next guitar, the Warlock, featured a shape inspired by the Bich—and it went on to become one of the most iconic B.C. Riches. The Widow, designed by Blackie Lawless, and the Stealth, designed by Mockingbird user Rick Derringer, followed in 1983.

By that point, B.C. Rich had a complete catalog of distinctive instruments, and it wasn’t long before overseas companies like Aria were creating B.C. Rich knock-offs. Bernie went into survival mode and flew to Japan with Hiro Misawa to set up the B.C Rich NJ series, which stood for “Nagoya, Japan,” where they were made. “We knocked-off ourselves, basically,” says Stich.

“The first time we went to Frankfurt [Musikmesse musical instrument trade show], we had really nice guitars and people came up to us and said, ‘Hey, that’s a copy of the Aria guitar.’ We were, like, ‘You’re kidding, right?’”

The company’s first Japanese guitars were labeled B.C. Rico and did not feature the NJ series designation. Trouble appeared soon after when Rico Reeds (makers of saxophone and clarinet reeds) sued B.C. Rich for patent infringement on the name. “We were, like, ‘Wait a minute! Rico is the guy’s real name.’ But instead of spending money on a big litigation and lawsuits, we just [substituted] an ‘h’ at the end of the name,” recalls Stich.

Stich with a custom-finished Mockingbird (left), and with future-star Lita Ford

playing a red-stained Mockingbird in 1980 (right).

B.C. Rich continued to produce more unique-looking guitars such as the Ironbird, the Wave, and the Fat Bob, which was shaped like a Harley-Davidson motorcycle’s gas tank. However, to capitalize on the resurgence of the Fender Stratocaster’s popularity in the mid ’80s, B.C. Rich introduced the ST series—a straightforward double-cutaway that was a noticeable departure from the company’s legacy of flashy shapes.

|

The first pivotal point in B.C. Rich’s rise to widespread recognition came in 1976, when sound engineer Bob “Nite Bob” Czaykowski picked up a maple-bodied Mockingbird—the first one ever made—for Aerosmith guitarist Joe Perry. “All of a sudden, B.C. Rich was on the map,” says Stich. “In my opinion, if it wasn’t for Nite Bob, B.C. Rich would have been another flash-in-the-pan guitar company.”

The wild shapes of B.C. Rich guitars also attracted the attention of the producers of This Is Spinal Tap. Stich put some guitars together for the production, and in so doing, unwittingly became responsible for adding a new phrase to popular music’s cultural lexicon. “There was a meeting in my office to loan the guitars and basses. I was playing with a volume knob Larry DiMarzio gave me that went to 11. I showed it to them and explained why it went to 11.” The producers used it in one of the movie’s classic scenes, and the idiom soon became immortalized in the vernacular of guitarists and rock fans the world over.

The Changing of the Guard

In the mid 1980s, B.C. Rich saw major changes that would send the company in a new direction. Stich left in ’84 and Moser left in ’85. In ’87, Bernie entered into a marketing agreement with Randy Waltuch’s Class Axe, allowing them to market and distribute Rave, Platinum, and NJ Series guitars. A year later, Bernie licensed the Rave and Platinum names to Class Axe, which essentially took over importing, marketing, and distribution of the foreign-made lines. Soon after, complete control was turned over to Class Axe and B.C. Rich’s custom shop was disbanded. Class Axe licensed the name B.C. Rich in 1989.

During this period, quality control nosedived and the B.C. Rich name suffered. Bernie was out of the company picture for a few years, and during that time he produced Mason Bernard guitars— handmade acoustic-electrics and Strat-shaped electrics. In 1993, Bernie regained ownership of B.C. Rich and made a concerted effort to restore the company’s name. Sadly, on December 3, 1999, he passed away from a sudden heart attack. Subsequently, the company went to his son Bernie Jr., who turned over control to the Hanser Music Group in 2001 and began making guitars under the Rico Jr. name. However, he is involved with some current B.C. Rich custom-shop guitars.

As part of its recently revamped custom operation, B.C. Rich also brought famed builder Grover Jackson aboard to work on the Gunslinger Handcrafted series. The company continues to evolve and release visually striking designs that, like its legacy designs, appeal to both younger metal players and elder statesman of the genre like Slayer’s Kerry King. Its Pro X Bich model was voted Best of NAMM in the electric guitar category at NAMM 2011.

Mötley Crüe bassist Nikki Sixx with his B.C. Rich Warlock—which is outfi tted with two splittable

P-style pickups, a multitude of switching options, and a reverse headstock—at a 1983 photo

shoot in Hollywood. Photo by Andy Caulfield