Mini pedals are immensely practical. I fantasize about traveling with a little board populated exclusively by them. And were it not for my attachment to a few old favorites, I might have already pivoted to an exclusively mini-pedal rig for any trip involving checked baggage.

Electro-Harmonix is a relative newcomer to the mini-pedal sphere. In fact, most of their efforts at miniaturization involved taking pedals like the Big Muff and Electric Mistress that were quite large and reducing them to sizes more in line with other company’s standard-sized stomps. But if they were a little late to the game, EHX, as they will, entered the marketplace with a sense of style and adventure. Each of EHX’s nine new Pico pedals, as EHX calls them, are part of the digital NYC DSP series. Curiously, confinement to the digital realm means this set of Pico releases is without legendary EHX pedals that would be logical candidates for miniaturization—most notably the Big Muff. But what the new Pico pedals lack in predictability, they make up for in color: Some of EHX’s most interesting pedal ideas are part of this series.

In imagining possible combinations of these nine pedals, it occurred to me that you could fashion a lot of very unique tone palettes from just a few of them. Though each of the pedals reviewed here—the Pico Attack Decay, Pico Oceans 3-Verb, Pico Canyon Echo, and Pico Deep Freeze—are evaluated on their own merits, they were selected with the notion of creating a little psychedelic sound laboratory. And while you can wring conventional sounds from these four pedals, their capacity for weaving weird and complex patterns of sound speaks to the exciting potential of these little stomps and EHX’s enduring sense of irreverence and invention.

Pico Attack Decay

The original EHX Attack Decay, an analog volume envelope that first appeared around 1980, was called a “tape reverse simulator” for its ability to generate reverse-tape-like volume swells. It’s an odd bird—even by EHX’s lofty standards. Next to the analog original, which came in a Deluxe Memory Man-sized enclosure, the Pico version is pico indeed. But this version is derived from the digital reimagination of the effect that appeared in 2019. That permutation includes a built-in fuzz, expression control, presets, an effects loop, and preset capability, but I’d guess that more than a few players will be more tempted by this smaller, streamlined version.

It's easy to create the volume swell effects that give the Pico Attack Decay its tape reverse simulator handle. You put the pedal in mono mode (activated by the small poly button), set the attack knob around the 10 o’clock position, and park the decay to the right of noon. The reverse tape effect can be pretty uncanny, and it’s fun to play leads and melodies using pre-bends, odd intervals, and off-beat timing to achieve more authentically disorienting reverse effects. These settings also make the pedal a nice stand-in for a volume pedal for simple melody lines. Certain fast attack times mated to shorter decay times produce clipped, no-sustained tones or stuttering, fractured tremolo textures. The former sounds especially amazing paired with fast echoes and long repeat times from the Canyon delay—creating spacey Joe Meek-style percolations. Used in mono mode exclusively, the Attack Decay can seem limited. Using poly mode doesn’t add oodles of additional textures, but it does often add a vowelly, mutant flange/filter effect that’s good for alien envelope-filter tones, which, again, sound pretty incredible with a heap of echo.

For the right player, the Pico Attack Decay can be an effective way to reshape instrument timbre and create interesting, off-kilter versions of volume-swell, envelope, and even bizarre staccato modulation effects. At just 20 bucks less than the larger, full-featured Attack Decay, the small size may be the main appeal here. But that mini footprint can make the difference between a niche effect making the cut when space is tight.

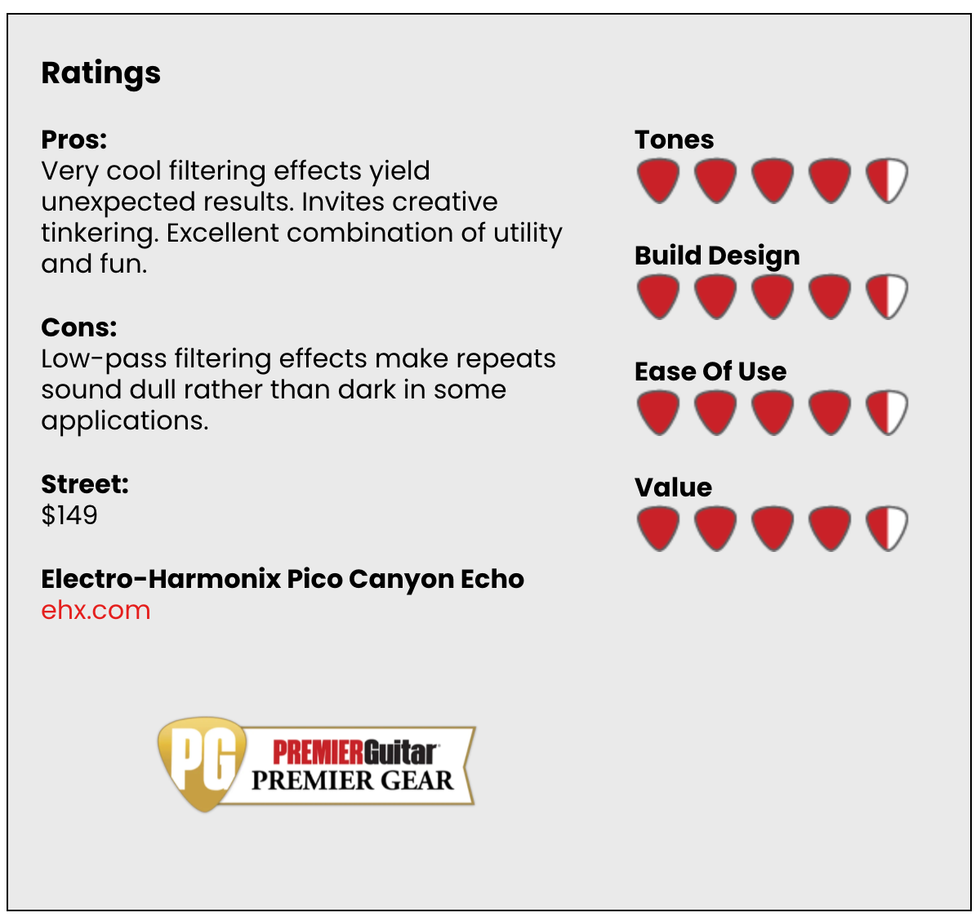

The Pico Canyon Echo is as engaging as any delay I can think of in a package this size. It’s flexible and full of surprises, thanks in large part to the cool filter control, a super-wide 8-millisecond-to-3-second delay range, and an infinite repeats function that effectively functions as a looper.

Sans filtering, the Pico Canyon’s basic delay voice is fairly neutral, which is no bad thing, and it’s certainly not chilly the way some digital delays can be. Introducing the filter, however, steers the Pico Canyon along unique tone vectors, particularly when you use the super-short, ADT-style delays. The filter moves between neutral no-filter sounds at noon and low-pass and high-pass settings on either side of the dial. Depending on where you set the filter and feedback control, these short delays can produce ring-modulation-like tones, lo-fi AM radio colors, and resonances and feedback effects that change dramatically depending on your pickups, amplifier, and playing dynamics. It also yields unexpected sounds that you don’t necessarily associate with delay. The filter control isn’t exclusively for oddball sounds, though. The low-pass filter adds darkness to repeats that hints at BBD delay sounds and is particularly effective for adding fog to long feedback settings. The high-pass filter, meanwhile, can lend digital crispness or ringing and howling Space Echo-style resonances with long feedback times.

Though weird sounds abound in the Canyon, it is a delay of great utility too. The tap-division button enables fast switching between eighth-note, dotted eighth-note, and quarter-note divisions, and it features a tap tempo function. With an appealing $149 price tag, I’d be tempted by the Pico canyon if it was twice the size. The combination of small size, straightforward functionality, interactivity, and flat-out fun make it an extra attractive delay option that will tempt players across many styles.

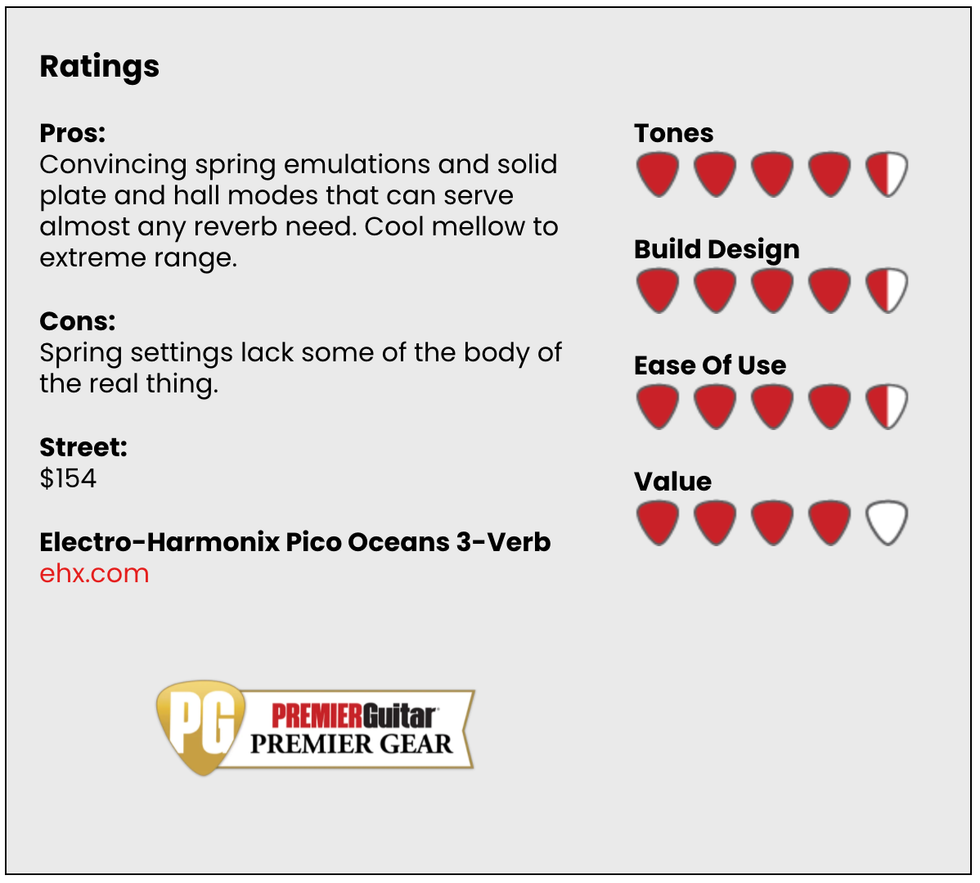

Like the Pico Canyon, the Oceans 3-Verb inhabits a crowded market space that ranges from ultra-low-priced imports to fancier fare. But while the Pico Canyon distinguishes itself from the competition with a wide range of straight-ahead to weird sounds, the Oceans 3-Verb mostly focuses on fundamentals. Here, that means digital emulations of spring, plate, and hall reverbs. The 3-Verb’s one great wild-card feature is its infinite reverb, which works in the hall and plate settings. It’s an awesome addition that ups the fun quotient exponentially and makes the 3-Verb an appealing option for noise, drone, ambient, and other experimental artists.

The 3-Verb’s voices each capture the spirit and quirks of their inspirations—often with great fidelity. The most subdued voices all add classy ambience that pairs nicely with drive pedals, adding air without turning gain-activated overtones to a filthy wash. Differences between the hall and plate reverbs are most discernible at these less-intense levels. Hall reverbs are tight and reactive with the tone, time, and pre-delay levels at modest levels. Add a little treble and you’ll hear a nice approximation of tile reflections. The plate reverb sounds most distinctively authentic with a little extra treble, pre-delay, and decay time, lending the slightly metallic and ghostly overtones that make real plate reverb so delicious. Both hall and plate reverbs can be taken to stranger lands, particularly when you add a generous helping of pre-delay, which can evoke Kevin Shields’ reverse-reverb tricks or add endless miles of ambience. At these more extreme settings, the hall reverb tends to emphasize high-octave content, while the plate is more diffuse and spectral. In both settings you can use the infinite reverb effect, generating huge washes that are beautiful when mixed with droning feedback.

As solid as the plate and hall reverbs are here, the spring reverb is the hit of the bunch. It doesn’t have quite as much body as a real Fender Reverb unit or the splashy reverb in the mid-’60s Fender Vibrolux I used for comparison. It’s also basically brighter than those two reverbs. But it is really no less awesome or fun for those differences. At advanced tone settings and in the large tank mode, it practically becomes a caricature of spring reverb. This is not a diss. I’ve gone looking for this tone many times in order to achieve extra-big-picture surf or Fillmore psychedelia sounds and come up short. It’s the kind of spring reverb that can absolutely slice through a recorded mix—even a busy one. I’d even venture that many players would pick this over the real thing.

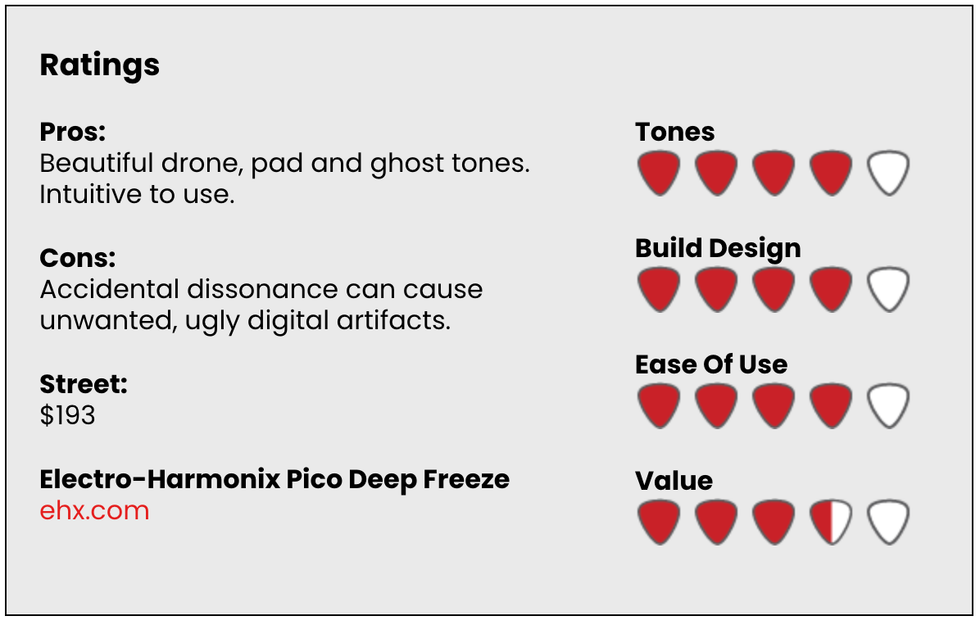

Not every player needs an EHX Freeze. But a lot of players don’t know what they’re missing. The Freeze inhabits an interesting place among guitar effects. It is, in effect, a little sampler that grabs your signal and freezes it for a given period—sometimes infinitely. A freeze is different than just a sustained tone. There is a lag in a freeze capture that can add many overtones. They can be pretty or ugly, depending on the moment you capture, the relationship between dry and effected signal, and how long you freeze the audio picture you capture. Put another way, the Freeze can be a drone machine, a chilly digital cimbalom, a tamboura in a box, a synth-generated sine wave, a freeze-frame ring modulator, or a distant ship’s horn sounding through the fog. Getting predictable and harmonious outcomes can take a steady hand, a bit of concentration, a smooth touch, and familiarity with how the Freeze’s interesting controls interact. But in and among these strange tone relationships await interesting sounds that can add gobs of extra vocabulary to your electric guitar expressions.

The Deep Freeze features three modes of operation: latch, moment, and auto. In latch, Deep Freeze grabs and holds your signal at the moment you press the footswitch. In moment mode, the pedal holds the freeze for as long as you hold the foostswitch. In auto mode, the Deep Freeze grabs the last note you play, enabling you to freeze each note in a sequence. Controls for dry and effect manage the critical balance between dry and effected signal. Gliss controls the speed at which an existing freeze morphs into a new one. The speed/layer knob controls the volume envelope in auto or moment mode, and in latch mode, it controls the volume of the previous freeze as you layer in new ones. That probably sounds complex, but it’s surprisingly easy to feel out the interactivity between these controls.

If there is a fundamental bit of knowledge with which you must approach the Deep Freeze, it’s that it likes to capture pure notes or chord tones without too much dissonance, which will cause fluttering freeze tones colored with cold digital artifacts. If you want a prettier, more unadulterated freeze—particularly in latch and moment modes—it’s critical that you freeze the note or chord at the most harmonious point of its bloom. If you hit the switch right as you pick a note or hit a chord, overtones from pick attack that might otherwise go unnoticed turn into dissonant rattle. Likewise, pitch changes or irregularities—from hitting your vibrato arm as you freeze a chord, for instance— will turn into the same digital clatter. In auto and moment modes, I got best results by using a soft picking touch and waiting for the sweetest moment of a note or chord bloom to hit the switch. Harmonics, too, can make beautiful drones if you capture them at their most beautifully blossoming moment.