As a kid, my aesthetic leanings—particularly where guitars were concerned—were a little anachronistic and specific. In a time when canonical classics and shred machines ruled the collective guitar consciousness, I loved custom colors and odd shapes, so a sunburst Stratocaster, particularly one with a maple neck, was, to my eyes, downright uptight and institutional.

And if you had taken my 12-year-old self to some magical used-guitar Wonka factory where I could have my pick of anything, I probably would have passed over a fortune in vintage guitars for a sherwood green Jaguar and a Vox Berkeley amp, or something equally awesome and relatively short on long-term-investment return.

Such contrary views have softened over the years, though. And my new open-mindedness lines up rather conveniently with the 70th anniversary of the 1954 Stratocaster. To state the obvious, the 1954 Stratocaster remains, seven decades later, a future-gazing design. In many respects it is electric guitar design perfection—comfortable, balanced, full of varied tones, and fantastically ergonomic. I see that clearly now. And such vision, as it were, made this review of two 70th anniversary Stratocasters, from two ends of Fender’s price spectrum, a real pleasure. It’s a testament to the efficiencies and consistencies in modern guitar manufacturing that the $799, Mexico-made Player Series Anniversary 2-Color Sunburst Stratocaster and the $2,599 U.S.-made 70th Anniversary American Vintage II 1954 Stratocaster share so much in terms of feel, playability, and tonality. Such similarities also speak to the visionary simplicity and elegance of the Stratocaster design. Much more than price distinguishes these instruments. Though expensive at $2,599, the 70th Anniversary American Vintage II 1954 Stratocaster has the feel of an heirloom—the kind of instrument that will hang behind the counter of the local guitar shop with a “do-not-play-without-asking” sign for eternity. And while the relatively inexpensive Player Series lacks the vintage precision and glamor of the American Vintage II, it is unquestionably a professional instrument that can hang in any gigging or recording situation and perform with aplomb.

70th Anniversary American Vintage II 1954 Stratocaster

If you obsess over vintage-guitar minutiae in the way a monocled entomologist studies variations in dragonfly wings, you could spend many seasons poring over differences among original 1954 Stratocasters as well as the reissues that honor them. In its first year of manufacture, the Stratocaster underwent several tweaks, changes, and refinements, some of which lasted mere months. In fact, though they number in the hundreds, Fender considered Stratocasters made before October 1954 “pre-production” models.

Most distinguishing design details on the Anniversary American Vintage II 1954 Stratocaster suggest an instrument made sometime around the middle or later part of 1954. Mini-skirt knobs, a “football” pickup switch, and rounded edges on the pickup covers are copied to the letter. Eight screws affix the single-ply pickguard to the body rather than the 11 used on later Stratocasters. The saddles are stamped with “Fender Pat Pend.” And the tuning machines are shaped like Kluson’s “no-line” tuners, used up to 1956. (By branding the machines with “FENDER” down the centerline, Fender effectively created a mashup of the ’56 “single-line” Kluson and the no-line configuration used in 1954, but I think we can be charitable and give Fender a pass here). The most arresting period-correct detail for casual Strat spotters is the headstock. With its gentler curves just below the “F” in the Fender decal and under the “R” in Stratocaster, it’s a reminder, perhaps, that the Telecaster remained fresh in the minds of Leo Fender and Freddie Tavares.

Befitting a guitar that costs north of $2,500, the AV II 1954 Strat is immaculately built. Our review specimen, at 8.6 pounds, is a little heavy for an ash-bodied Strat, but like most Strats, feels perfectly balanced. If our review guitar is heftier than the average ash Strat, it might be down to the extra mass in the chunky 1-piece maple neck. Fender calls the neck profile a “1954 C.” It feels more D-like to me, but regardless of profile its relative heft is a lovely thing and a welcome alternative to the love-it-or-you-don’t V profile on the similar American Vintage II 1957 Stratocaster or the slimmer, more generic C shapes that make up so many contemporary necks. Finding a guitar that feels just right can be harder than finding one that sounds good. And for some players this neck alone could justify the splurge-y price. If you have small hands or shreddy tendencies, it might not be your thing. And even for players with average or larger-sized mitts, the extra substance could lead to hand fatigue if your playing style or technique are at odds with the larger dimensions. Certainly, it’s different enough from the contemporary norm that you’ll want to spend a while at a shop with one before you commit to purchase. But I love the way the neck, and the 7.25" radius facilitate languid, lyrical string-bending and vibrato. And personally, I find the thicker neck less conducive to hand strain than slimmer necks that compel me to squeeze a bit more.

Ring and Zing

Stratocasters can sound pretty bright, and this 70th Anniversary AV II edition could probably shatter glass at its trebliest. But it also reminded me how much air and breath lives in a nice Stratocaster, how balanced and un-bossy they are in most contexts, and how responsive and sensitive to dynamics they can be. The pickups, which are built around alnico 3 magnets, are pretty quiet. But the output is discernibly more dimensional, open, and alive in the high-midrange than the alnico 5-equipped Player Series Stratocaster or the ’80s E-Series Stratocaster I also used for reference.

The bridge pickup can be a firecracker, but you hear a lot of detail, too. Hot transient notes give way to chiming overtones that blossom even more for the guitar’s perceptible resonance and sometimes surprising sustain. By picking hard and close to the bridge, you can coax a lot of raunch. But use a gentle fingerpicking touch with just flesh and nails up closer to the neck and the bridge pickup turns warm and quite civilized. As with any vintage-correct 1950s-style Stratocaster, there’s no tone control for the bridge pickup, but the dynamic range you can achieve with variation in picking intensity, technique, and position won’t leave you longing for one, either. I don’t gravitate toward the middle pickup on my own Stratocaster, but I lived there a lot in my evaluation of the AV II 1954. The spectrum of available tone shades sounds and feels especially wide and makes a beautiful platform for exploring quasi Richard Thompson-isms (particularly with a detuned 6th string—yum!) or tender, bubbling Velvet Underground tones. Like the bridge pickup, the middle showcases the AV II 1954’s sustain and resonance, and is particularly bloomy. The neck pickup, too, is honey sweet. As with the middle pickup, a detuned 6th string highlights expansive dynamic range and a rich overtone palette. With the tone control wide open, you can create major tone contrasts from this pickup alone, but a little tone attenuation goes a long way toward making the neck unit very, very mellow. Predictably, Curtis Mayfield or Hendrix-style soul-ballad phrasings sound magical at either setting. And if you’re wondering if you can sneak the 3-way switch into the out-of-phase 2 and 4 positions you’d get from a 5-way switch, the answer is an affirmative—as long as you use a tender touch. It doesn’t take much to knock the switch back into one of its three natural positions. But if I didn’t get too enthused, I could keep the switch in out-of-phase positions, and it sounded wonderful.

The Verdict

Sure, $2,599 is a lot of money to pay for a Stratocaster, and apart from the Jimmy Page Mirror Telecaster, it’s as expensive as any vintage-spec Fender that doesn’t come from the Custom Shop. For some customers and collectors that love limited edition runs, the 70th Anniversary distinction and accessories that come with the guitar will justify the price. But if you know you want a Stratocaster and long for something a little special, it might be worth saving up or selling some deadweight instruments to make room for this one. In terms of tone and playability, you are unlikely to regret the investment, and it’s fantastically versatile.

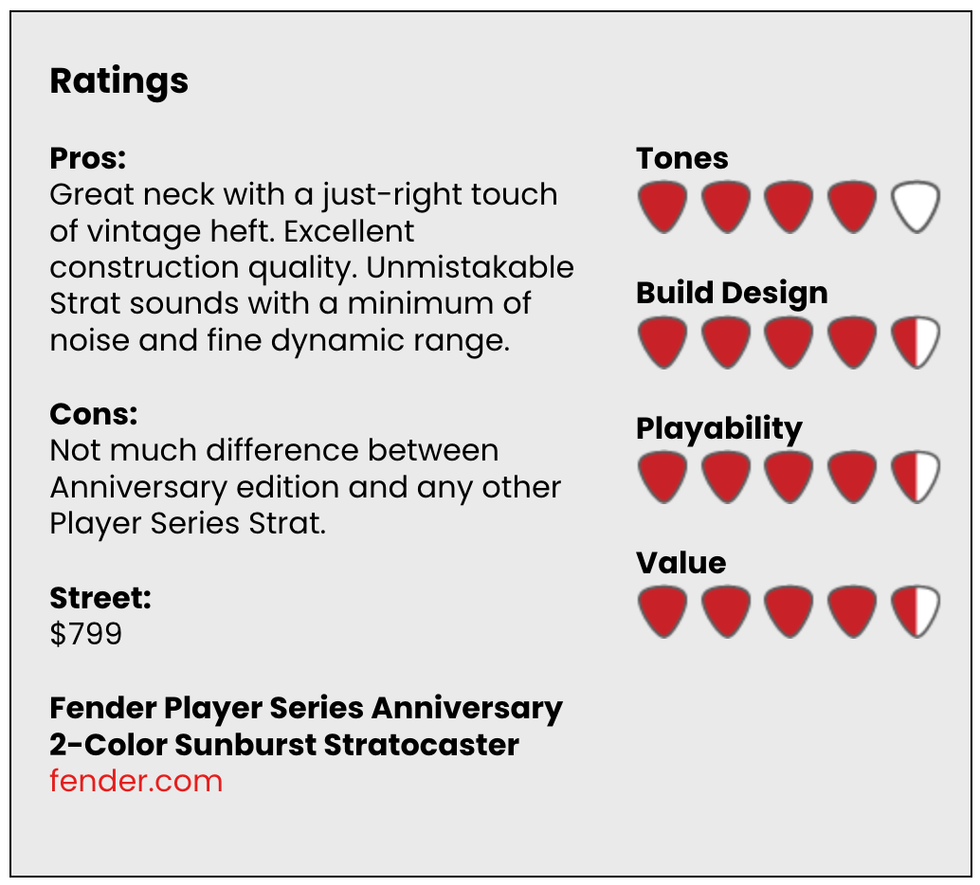

Fender Player Stratocaster Anniversary 2-Color Sunburst

The Player Series version of the 70th anniversary Strat.

I think Mexico-made Fenders are awesome. A lot of my friends do, too. Some have made MIM Fenders their No. 1 instrument. And though a few may have switched in new pickups or made modifications here and there, I’ve heard some of the same people express regret for spending money on improvements that didn’t improve the guitars in any measurable sense. If you get a good one, Mexico-made Fenders are still among the best deals in the business, and our review Player Stratocaster Anniversary plays beautifully, sounds exciting and pretty, is built rock-solid, and exudes plenty of mid-century Stratocaster essence.

Milestone Mishmash

If the AV II 1954 Stratocaster is an exercise in vintage exactitude, our Player Series Anniversary model (which makes no claim to year-specific accuracy) is a more hodge-podge homage to the Stratocaster’s early years. While it can be had with a maple neck, our review version came with a pau ferro fretboard and a 3-way pickup that makes it a sort of mid-’50s/early-’60s mashup. Design cues like the 2-color burst and spaghetti logo nod at 1954, but the tuning pegs, 9.5" fretboard radius, 5-position switch, 22 medium jumbo frets, headstock truss-rod access point, and bridge-pickup tone control are all trappings of a contemporary Strat. And though the neck fills the hand in a comfortable, vintage-y sort of way, it’s listed as a modern C profile, just like non-anniversary guitars elsewhere in the Player Series. The most distinctly 1954-like feature, really, is the finish, which is handsome, understated, lends a more classic air, and actually looks great against the pau ferro fretboard, which would usually accompany a redder, 3-color, ’60s-style burst.

Vibes for Less

You could play a guitar like the Player Stratocaster alongside a Strat as nice as the AV II 1954 anniversary model and end up feeling flat and disappointed—or you could be pleasantly surprised. My experience was distinctly in the latter category. While the alnico V Strat pickups (which are also the same as those found elsewhere in Player Series Stratocasters) lack the oxygenated, widescreen dimensionality of those in the AV II 1954 Strat (this goes for the middle pickup in particular), they communicate the unmistakable sonic signature of a Stratocaster with a bit more punch and authority. The bridge pickup, which in this case can be modified via the same tone control that governs the middle pickup, sounds snappy, surfy, garage-y, or can drive a fuzz to banshee-scream feedback extremes. The neck pickup, too, sounds delectable in all the ways that you want from the mellower side of a Strat. It’s a perfect mate for lyrical, melodic phrases and spare bluesy picking which benefits from the guitar’s excellent sustain properties. For a relatively inexpensive Strat, the Player Series is pretty quiet, too. Sixty-cycle hum goes with the territory here, but it is subdued and never distracting.

The Verdict

The Player Series Stratocaster is perennially among the best-selling electric guitars in the universe, and this 70th Anniversary edition makes the appeal easy to understand. Though it’s not a detail-for-detail 1954 Strat replica, the substantial neck (save for the glossy finish) exudes vintageness. And it definitely sounds classically, unmistakably Strat-like when you track it. For a guitar put together with so much care, $799 is a very attractive and fair price. And while its American Vintage II Anniversary counterpart may exude the essence of an heirloom, the Player Series sounds sweet and feels solid, stable, and familiar enough that, to paraphrase an old Fender ad campaign chestnut, you won’t want to part with this one, either.