Many different effects can salvage a crappy backline situation. A nice reverb goes a long way toward making a lame amp sound okay. A delay or compressor can usually lend a little energy and mystery to an otherwise lifeless tone, too. But in my experience, few effects coax magic from garbage quite like tremolo.

Mariner Tremolo

Just ask Keith Richards. For the spooky-as-hell guitar track that underpins “Gimme Shelter,” Keith used a Triumph solid-state amp that legendary engineer and producer Glyn Johns hated. But while Johns may have thought the Triumph sounded lame, it had a tremolo circuit Keith loved. Go ahead, give the song a listen. It’s hard to imagine “Gimme Shelter” without that haunting pulse.

Maestro Mariner Tremolo Pedal

Maestro’s Mariner tremolo has the same potential to rescue a lifeless track or performance. It’s not the most refined tremolo (it can come on a bit strong at times), nor does it sound like an approximation of any vintage standard. (It sounded very different from a black-panel Fender Tremolux and Vibroverb, as well as an excellent digital take on those circuits.) Functionally speaking, it will probably remind many players of the Boss TR-2, with its depth, speed, and wave shape controls, which move between sine and square waveforms. Even its controls are arranged in an inverse triangle like the Boss. But the Mariner offers a second, more phase-y mode that it calls harmonic tremolo, which approximates, to some extent, the harmonic vibrato on some early-’60s Fender brown-panel amps. That extends the practical and fun potential of the Mariner.

Pick Your Pulse

If you’re a stickler for vintage-correct emulations, Mariner might not be your first pick for a pedal tremolo. That doesn’t mean it lacks vintage feel, though. In classic mode (it’s not clear if this all-analog circuit was designed to approximate an optical tremolo circuit, bias tremolo, or neither), you can dial in very pretty, immersive modulations that will sound more than adequately vintage-like in a mix. Classic settings are also easy to shape in creative ways with the waveform knob. Compared to what’s arguably the affordable analog tremolo standard bearer, the Boss TR-2, the Mariner’s maximum depth and square wave settings are more pronounced and intense. Some of this intensity might be due to the fact that the Mariner is flat-out louder. Tremolo-pedal makers often build in a very mild boost to compensate for the perceived loss of signal that accompanies some tremolo effects, and Maestro certainly seems to have included one here. The Mariner is perceptibly louder than both a TR-2 and a Strymon Flint.

Even still, Mariner’s harmonic mode is rich and charming, and the wobbly pulses lend a very psychedelic edge.

The Mariner could be more nuanced at times. The classic mode’s pulses, for instance, sometimes seem more hard-edged than liquid. These less-fluid modulations can be even more pronounced in the harmonic tremolo mode. Many players, however, will prefer this texture, even though amp-based harmonic tremolo tends to sound smooth and contoured. Still, Mariner’s harmonic mode is rich and charming, and the wobbly pulses lend a very psychedelic edge. And at slower rates, in particular, the harmonic mode finds its stride. The modulations are phasey and elastic and can sound both beautiful and striking in the right setting.

The Verdict

At nearly 160 bucks, the Mariner is priced near the top end of the affordable tremolo class. But Mariner’s secret weapon may be the fact that it sounds vintage without clearly imitating other circuits or sounding too generic. That relative individuality, plus its extra output, make it an appealing option for those who’d rather not default to the most obvious standard.

Orbit Phaser

One of my favorite ways to make a tremolo pedal like the Mariner sound even cooler than it already does is by situating a phaser downstream. I tend to disagree with guitarists that regard phase as one-dimensional. I’ve seen ripping players with great dynamic touch and broad tone palettes that almost never turn them off. And it’s always impressive how they weave a phaser’s cool mysterious sense of motion into a complex whole instead of placing the modulation front and center.

Maestro Orbit Phaser Pedal

There’s a lot more flexibility to do that these days now that phasers have evolved so considerably from early one-knob classics. Maestro’s Orbit Phaser walks the line between contemporary and complex, and vintage and stupidly simple, though it tends toward the latter. So, while it lacks some of the fine-tuning features you see on more powerful units, it facilitates creation of subtle, backgrounded blends and much more prominent modulations.

You Gotta Move

The Orbit’s phase is bold and clear. There is no perceived signal loss—a problem that plagues a lot of older analog phasers and which becomes a fear among many first-time phaser shoppers. In some situations, the Orbit cuts because of a very pronounced midrange emphasis. The pedal adds a distinct tone color—midrange-y enough to evoke a cocked wah or filter at certain settings and with certain guitars. There are some awesome applications for the voice. For example, I paired the pedal with a Telecaster on which I rolled the tone way back. The resulting skwonky waveforms I heard could transform an otherwise dull part into something hooky and weird. The midrangey voice also meshes very nicely with PAF-style humbuckers, creating pronounced, muscular waveforms that cut in jangly settings or psychedelic blues solos. The Orbit sounds extra cool and assertive at fast modulation rates—another neat way to pepper up a same-old fake-Jimi solo. It also sounded bolder in this setting than the very old and familiar Small Stone and Phase 90 I used for reference.

The Orbit sounds extra cool and assertive at fast modulation rates.

At slower rates—the kind that, say, you would use for The Dark Side of the Moon tracks, soul ballads, or Waylon Jennings jams—the Maestro’s mid-focused voice works less well. Rather, the more open-ended and less specific voices of the Phase 90 and Small Stone let your signal breathe a lot more across the frequency spectrum, while the Orbit feels punkier and more snarling. Which flavor is better is totally subjective. But I would say Orbit’s slow phase tones read as a little less liquid than those from the old MXR and Electro-Harmonix units.

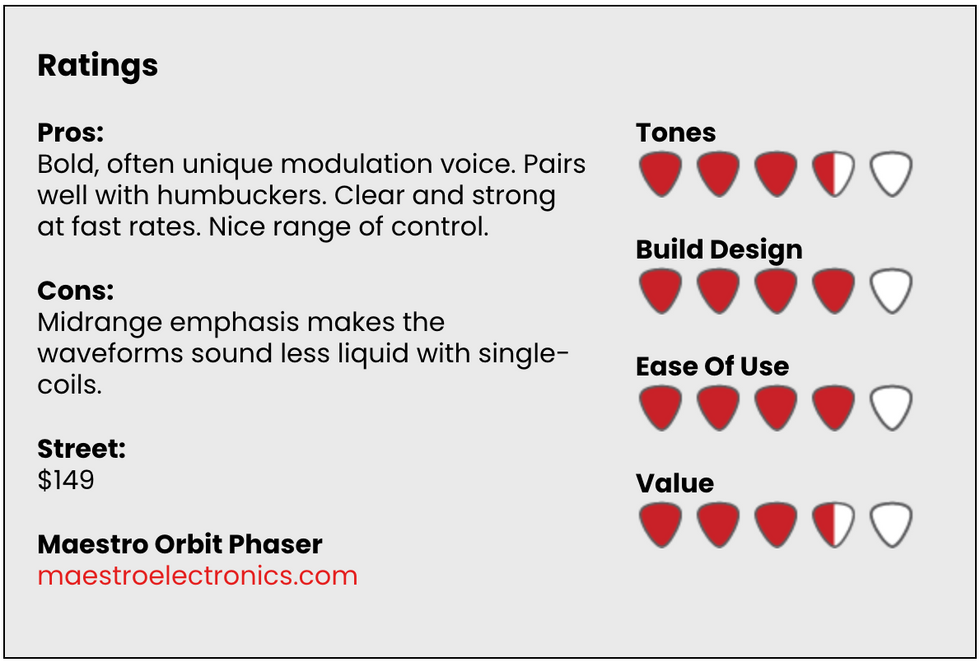

The Verdict

The Orbit Phaser can be a real joy for how unique it sounds. Faster rate settings are particularly rich. The ability to tailor width and feedback enables loads of contrasting subtle-to-robust waveforms. The 4-and-6-stage modes provide additional versatility, though the differences between them is less pronounced than on some phasers with that option. The Orbit’s range would make it the ideal candidate for an always-on phaser, and there will be players who use it in just that fashion. But the strong midrange emphasis will probably dissuade many from using it that way— especially those that primarily use single-coils. Humbucker players might have a different experience. The Orbit’s voice gets along great with a PAF. And that’s just one of many intriguing and satisfying sounds here.

Agena Envelope Filter

To a large segment of the guitar-playing populace, “envelope filter” usually means “auto wah” or “that quacky thing.” Most good envelope filters do that stuff. It’s probably what most buyers expect of them. But envelope filters can do other really cool things. They can effectively work like high-contrast EQ presets—transforming solos as radically as a fuzz can. They can also work like dynamic phasers and summon interesting phrasings from pedestrian chord changes and melodic lines, particularly when you get used to working in bendy, elastic give-and-take tandem with the effect. Correspondingly, they are great tools for digging out of a rut.

Maestro Agena Envelope Filter Pedal

Maestro’s Agena lives a little less on the quacky end of the filter spectrum, trading some of those hyper-vowely, percussive and snappy filtering qualities for a more expansive dynamic palette and a little more control over attack. But for anyone keen to explore the effect beyond Jerry Garcia and Bootsy Collins sound archetypes, it will seem much more forgiving and usable than many more clearly Mu-Tron III-derived circuits.

Practical in Practice

If you’re at all put off by envelope filters because their controls are counterintuitive on the surface, you should not fear the Agena. Even if you’re not familiar with how envelope filters are supposed to work, it’s easy to feel your way through how they interact and respond to the input from your guitar and fingers.

The sense knob governs how much picking energy is required before the envelope is activated. Attack controls how fast the envelop opens. Decay regulates how long the filter stays open. A small toggle will be familiar to old-school Mu-Tron and Electro-Harmonix Q-Tron users. It assigns emphasis to higher or lower frequency ranges. The controls are fairly interactive. You can set up classic quacky sounds by cranking up the sense and attack controls and situating the decay control in the middle third of its range. More subdued, less vowel-y tones lurk at faster decay rates, where you can also coax great narrow-focus filter sounds that evoke old octave effects like the Ampeg Scrambler or Dan Armstrong Green Ringer.

You can also coax great narrow-focus filter sounds that evoke old octave effects like the Ampeg Scrambler or Dan Armstrong Green Ringer.

Because the Agena is a dynamically controlled filter, it responds to any change in your input signal. So, it reacts differently to varied pick attack and heavier or thinner picks. Boosts and overdrive remove dynamic range but can add emphasis to quacky and vowelly filter responses or filter effects that highlight specific frequencies. Different guitars and pickups can have very different relationships, too. Telecaster bridge pickups were especially good for coaxing dynamic phase sounds at high-sense/fast-attack/medium-decay settings. PAF-style humbuckers, meanwhile, sounded hot and vocal.

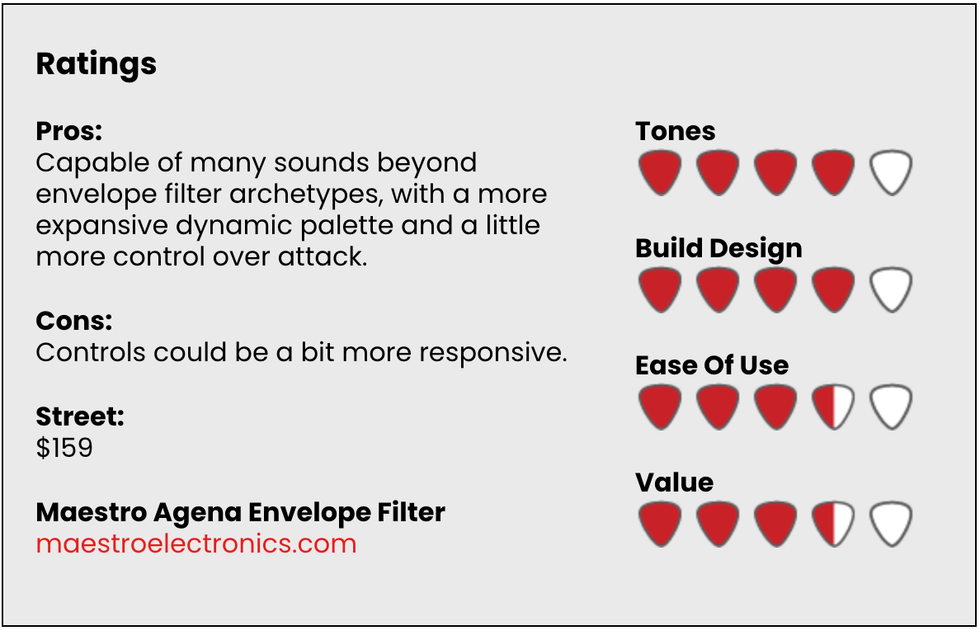

The Verdict

In some ways, the Agena could be the envelope filter for people that don’t like envelope filters. It rarely feels like an all-or-none proposition, and the filter is capable of many sounds in between Grateful Dead caricature and less loaded voices. It also rewards players who pursue less obvious, droning playing approaches as opposed to those who play it funky. But even if it’s just classic quack you’re after, the Agena gives you many shades to work with.