Since I began repairing guitars professionally in 1990, thousands of instruments have crossed my bench. Many were used guitars purchased by owners who thought they were getting a great deal, but were later surprised to discover their instrument needed extensive repairs. Music stores, online auctions, and pawnshops can be a great resource for buying a used instrument, but you need to keep your eyes open. What you don’t see can and will cost you.

Here’s a list of things to check before buying a used acoustic guitar. These are issues that are typically overshadowed by sexy features, but they can cost more to repair than the value of the instrument. My hope is that armed with this knowledge, you’ll avoid making a costly mistake when buying a used flattop.

Check the seams and joints.

One of the first things I do is inspect the glue joints—areas where different parts attach. I suggest starting with the neck joint. Does the neck heel fit tightly against the body? Relentless string tension can make the very end of the heel pull away from the body, as in Photo 1. Removing and resetting the neck costs hundreds of dollars, so in most cases, this type of gap is a deal-killer.

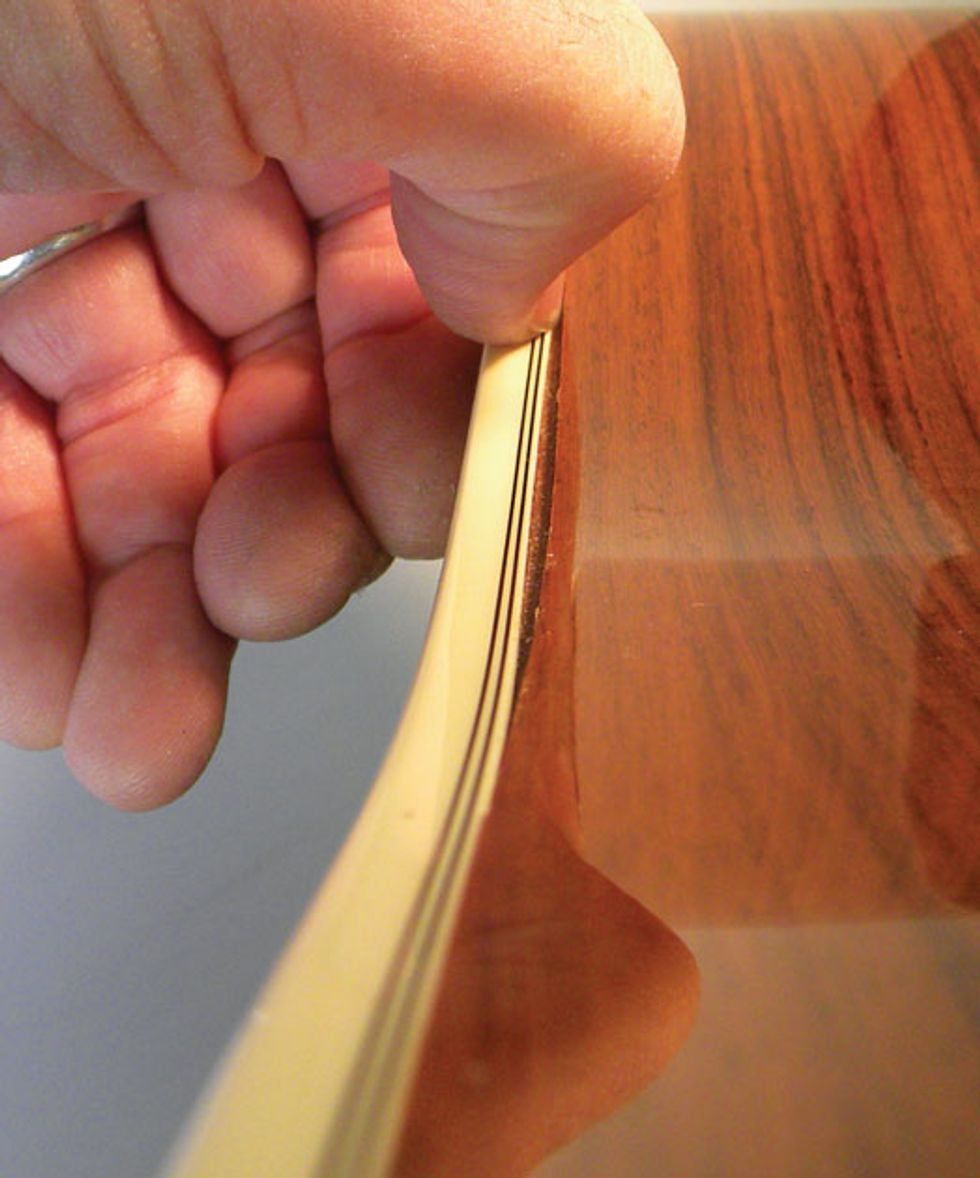

Run your finger along the binding to check its integrity, using your fingernail to identify any seams that are opening (Photo 2). Binding that’s separating from the sides, top, or back can be expensive to repair, especially if it’s deteriorating.

Photo 3

Got cracks? Always check for cracks in the wood. Potentially problematic areas include the vulnerable headstock, top, and back (Photo 3). Cracks can be a sign of structural failure or result from the guitar being exposed to low humidity—a common malady. Whatever the cause, cracks may cost hundreds of dollars to repair.

Photo 4

While you’re checking the surface, also look for buckles or waves on the top, which can indicate loose braces or a damaged bridge plate. Sometimes subtle buckles happen during the manufacturing process and are not a big deal. However, if the braces or the bridge plate have failed, it could cost hundreds of dollars to repair. (We’ll revisit the bridge plate in a moment.)

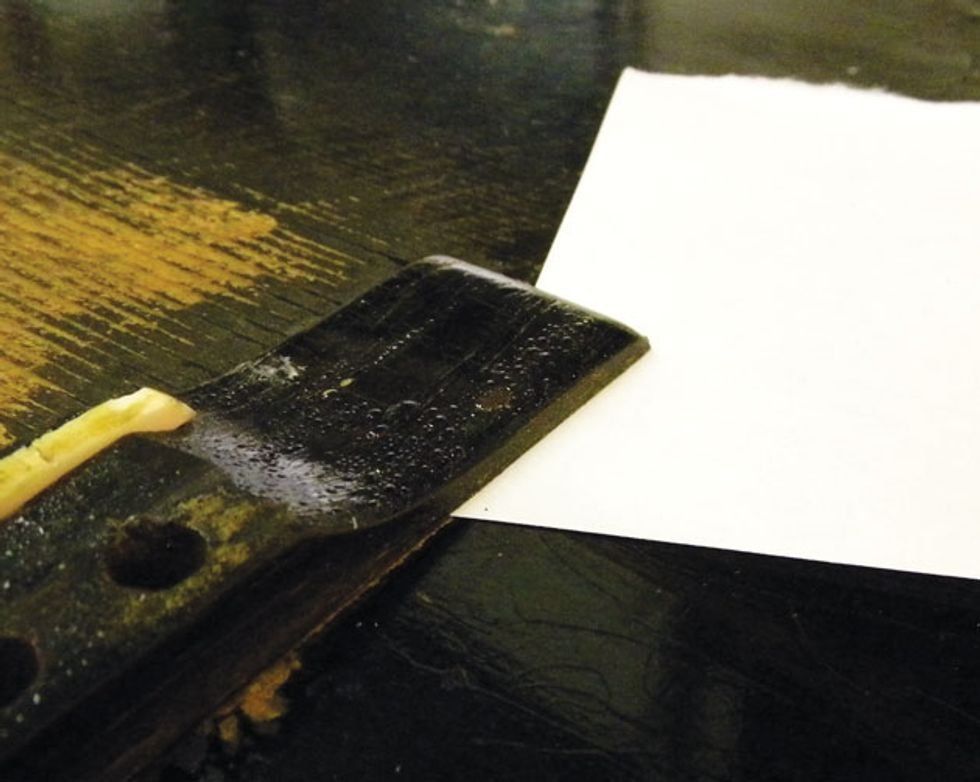

Bridge integrity. Spotting a loose bridge is usually easy—just look for any separation between it and the guitar top. To do this, simply slide a small piece of paper along the edge of the bridge to see if it slips underneath (Photo 4). If the paper slips into a gap, it’s likely the bridge will need to be removed and re-glued. This can cost from $90 up to $150, depending on how much time it takes to remove and reshape the bottom of the bridge.

Photo 5

If the bridge is cracked, especially along the pin holes or saddle slot (Photo 5), it must be replaced. It can be difficult to find an exact, factory replacement bridge that fits perfectly and intonates correctly. Typically, when I encounter this problem, I have to carve a new bridge out of a block of wood. Because it has to look and function exactly like the original, this is a very expensive proposition. A custom-carved bridge usually costs between $300 and $450.

Photo 6

Bridge-plate blues. Located inside the guitar right below the bridge, the bridge plate is tough to inspect for damage, but there are a few telltale signs to look for. If the wrap securing the ball end to the string extends over the saddle, the bridge plate is probably worn out. And if the bridge is cracked across the pin holes, the bridge plate is probably cracked as well. Either way, the bridge plate will have to be repaired or replaced. Why? A damaged bridge plate, like the loose and cracked one in Photo 6, can lead to brace failure, a cracked bridge, and cracks or splits in the top. The cost to replace a bridge plate can run from $350 up to $500.

Neck, frets, and fretboard. After examining the body, it’s time to investigate the neck. Start by sighting down the neck from the string nut to the body, while looking for any warps, twists, or the dreaded “ski jump” at the end of the neck. If a neck has any of these issues, the only way to permanently correct it is to plane and re-fret it. Additionally, if the frets have dents in them (Photo 7), they may need to be replaced. Always play each string up and down the fretboard to check for string rattle or muted notes—signs that the frets may require work. A re-fret job can cost anywhere from $300 to $600, so don’t rush this inspection.

Neck angle. This extremely important element determines an acoustic guitar’s playability, volume, and tone. If the neck angle is low in relation to the bridge, the action will be high, making the guitar difficult to play. Conversely, if the neck angle is high, the action will be too low.

Here’s an easy way to determine if a guitar’s neck angle is off: Look at the action at the 12th fret and then check the height of the bridge saddle between the 3rd and 4th strings. If the action is high at the 12th fret, but the saddle is short—less than 1/8"—the guitar has a low neck angle. If the saddle is tall (over 1/4"), but the action is too low, it has a high neck angle.

Whether high or low, the guitar is losing volume and tone, and it won’t play as well as it could. A perfect neck angle provides comfortable action at the 12th fret with the saddle measuring between 1/8" and 1/4". This will leave enough room to adjust the saddle height as needed to accommodate seasonal changes.

If a flattop has a bolt-on neck—as many modern acoustics do—adjusting neck angle is a relatively inexpensive repair, about the cost of a setup. However, if the guitar has a dovetail neck joint, the repair can run $300 to $600.

Intonation. This describes how well a guitar plays in tune as you fret notes up and down the neck. Before you buy any instrument you should check its intonation, but this is especially true for an acoustic guitar because it doesn’t have individually adjustable saddles.

To check the intonation, you need a quality tuner. First tune the guitar to concert pitch, then pluck the 12th-fret harmonic on the 1st string. Watching the tuner, adjust the string until the harmonic is in tune. This is your reference pitch. Next, press the string down at the 12th fret, pluck that note and compare it to the 12th-fret harmonic.

Always play each string up and down the fretboard to check for string rattle or muted notes—signs that the frets may require work.

If those two tones differ, the guitar will not play in tune along the fretboard. Test each string this way and make a mental note of any discrepancies between the 12th-fret harmonics and corresponding fretted notes.

Correcting a guitar’s intonation can be as simple as re-carving the strings’ breakpoint on the original saddle, but sometimes it requires making a new saddle, replacing the string nut, or even filling and then re-cutting the bridge saddle slot. These repairs can cost from $70 to $300, depending on what’s required.

Repair cost versus value. If an acoustic needs some repairs, this doesn’t automatically mean it’s not worth buying. The real trick is to understand how much you’ll need to invest in relation to the guitar’s market value.

Sometimes investing in repairs can pay off handsomely. For example, I once had a client bring me a 1940 Martin D-18 in terrible condition. My quote for restoration was $4,000. That sounds like a lot to invest, right? As it turns out, he only paid about $800 for this vintage Martin. After researching the value of a 1940 D-18, I discovered that the guitar would be worth nearly three times what my client would spend on restoring it, so we went ahead with the project.

Of course, this isn’t a typical occurrence. Sometimes you may buy a guitar at fair market value, only to discover that it needs several hundred dollars of repairs. Now, as they say in real estate, you’re upside down.

To avoid this, spend the time to research the value of an instrument—and the costs to repair it—before you make a purchase. Also keep in mind that when a guitar has structural cracks, it lowers the value (even with a perfect repair), so it’s important to figure the loss of value into the equation.

If done correctly, repairs like a neck reset, re-fret job, or re-gluing a bridge won’t devalue an instrument. Researching the fair market value of a comparable instrument with similar repairs will help you decide if the one you’re considering is worth buying. If the repairs plus the cost of the instrument exceed its fair market value, I’d pass on the deal.

A final thought: If you’re unsure about the condition of an acoustic you plan to purchase, have a qualified luthier look it over before you buy. It’s like buying a used car: The small cost of a professional evaluation can save you big bucks and spare you potential headaches.