Country and jazz might seem like an unlikely combo, but there’s a rich history of collisions between these two idioms. Jazz musicians from Sonny Rollins to Bill Frisell have used cowboy and country songs as source material for improvisation, and country musicians like Bob Wills and Jimmy Bryant filtered their music through a jazz lens.

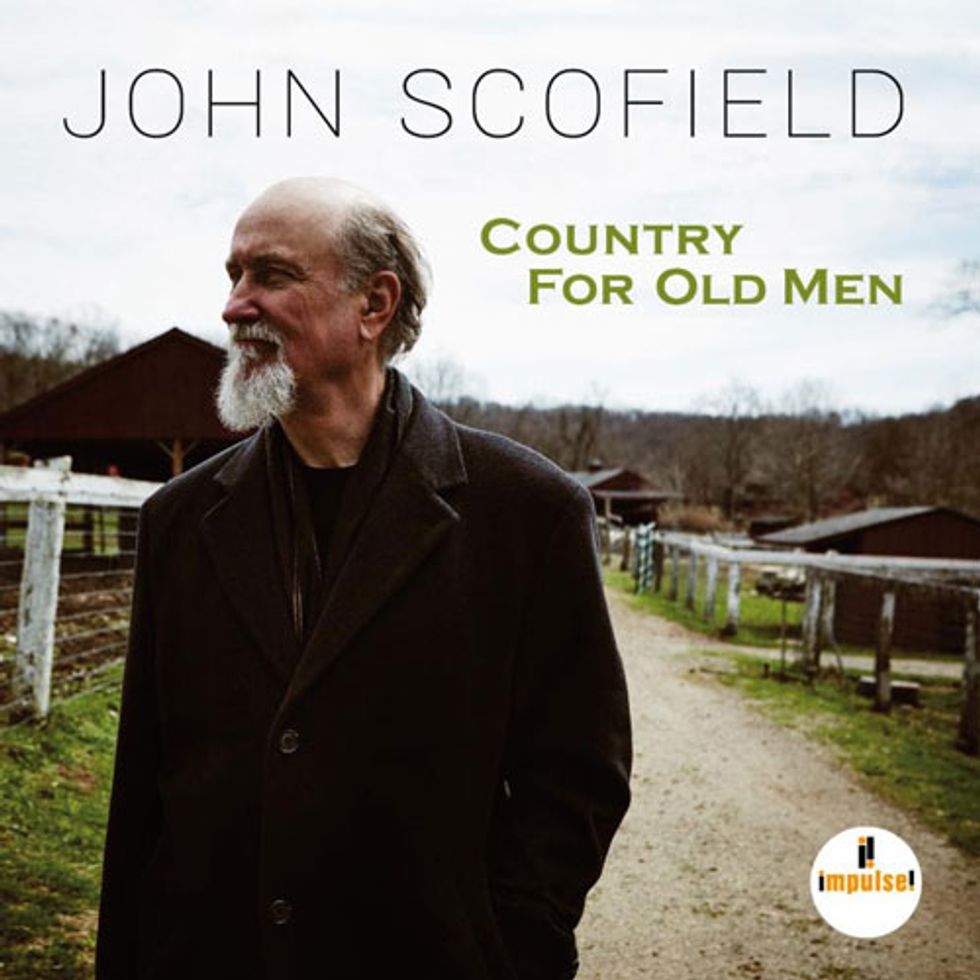

Jazz guitarist John Scofield has occasionally winked at country during his five-decade career, which has included stints with such jazz legends as Miles Davis, Charles Mingus, and Joe Henderson; collaborations with bands like Medeski Martin & Wood and Gov’t Mule; and more than 30 albums as a leader.

But Country for Old Men, the follow-up to 2015’s Past Present, marks the first time that Scofield has fully acknowledged his affinity for country. On the album, Scofield is joined by drummer Bill Stewart, organist and pianist Larry Goldings, and bassist Steve Swallow—all frequent collaborators. He transforms songs by George Jones, Hank Williams, Dolly Parton, and others into smart vehicles for bebop improvisation.

Whether or not you like jazz or country—and contrary to what the title suggests—Country for Old Men is an exciting outing with plenty to offer guitar fans of all stripes. As always, Scofield’s approach is anything but staid, and he delivers his angular bebop lines in the most compelling ways. Then there’s his unmistakable tone: warm and full-bodied, highly detailed, and so easy on the ear.

Scofield spoke with Premier Guitar the day before he took off for a European tour. He told us about how he gets that killer sound, how he learned to make his guitar sing like a country crooner, and described the strategies he used to put a jazz slant on country tunes.

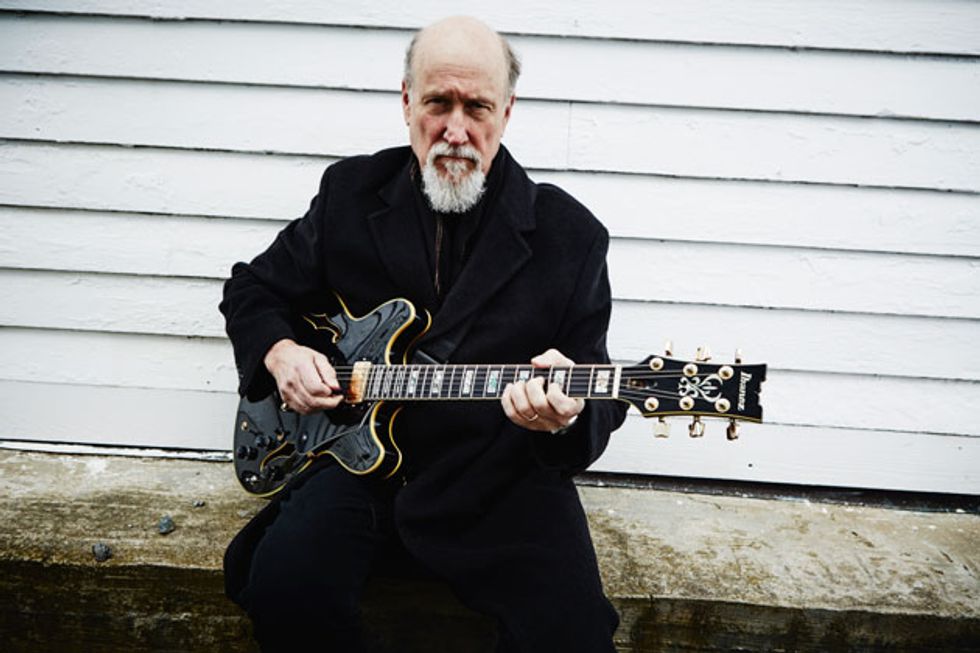

More often than not, you’re photographed with an Ibanez thinline. Is that what you used for recording Country for Old Men?

On the album, all I’m playing is an Ibanez AS200. I have two of them, and this is a black one they made for me in 1986, which I haven’t played as much. I also replaced the electronics with two Voodoo pickups—copies of old Gibson patent-applied-for humbuckers.

And then I didn’t use any pedals. I just went through my 1964 Deluxe Reverb that I bought maybe 15 years ago. It was kind of messed-up when I got it. The amp didn’t feel like it had enough power and it didn’t sound right. I had it looked at and somebody told me that the transformer looked wet. Turns out it had been in a flood and wasn’t performing correctly, so I put in a new transformer and the amp has sounded fantastic ever since.

You get such a nice warm sound, with a hint of overdrive. So that’s all from the amp?

Yep—the Deluxe is a good sound for me, cranked, but not all the way up. On that amp, I set it around 4 or 5, where I find a sweet spot, breaking up, but not too much. I think I had the reverb on a small amount, but didn’t use any tremolo on the record.

Do you play any guitars other than Ibanez semi-hollows?

I have a 1963 ES-335 that I got a long time ago, and I recently got a 1962 ES-330 that I really like. I’ve got an old Fender Telecaster, the guitar I bought in high school that somebody resold me about 10 years ago, and I have some Custom Shop Fenders. I have a nice old Gibson Howard Roberts as well. But I mainly play those Ibanez guitars because I’m used to them, and I really like the way they sound and feel.

Do you think you’ll ever use any of those guitars live or on recordings?

I’m not sure my 335 is the greatest example of that model. I like it, but it sounds a little uneven. I’m really tempted to use the 330, because I really like the sweet sound of those old P-90 pickups. But I’m not quite used to the feedback [that’s inherent to a fully hollow guitar like the ES-330] because I’ve been playing the semi-hollows for so long. So I’m waiting to use the 330 for some live situation where I can get used to it.

Country for Old Men is a great album title.

That came from my wife, Susan, who’s my business partner. I told her I wanted to make a record of country songs, and she goes [dryly], “Country for old men.” It’s a reference to No Country for Old Men, a fantastic novel by Cormac McCarthy that got made into a scary-ass Coen Brothers movie. I found out the quote comes from a poem by William Butler Yeats, “Sailing to Byzantium.” The first line is “That is no country for old men.” In any case, the title Country for Old Men cracked me up because, when I play, I see a lot of men my age in the audience.

How did the country project come about?

I’ve always liked country music: the classic stuff from Hank Williams to Buck Owens to Merle Haggard. I’ve been aware of the music ever since I started playing, but I’m by no means a country musician. I would get a record and get into some stuff as a fan every now and then. Not long ago I realized how you could turn some of these country tunes into jazz vehicles to blow on. So it’s really a jazz record with these country tunes. But when I play the heads, I really try to get a country kind of sound, which speaks more to the influence of the great singers than a specific style of country guitar playing.

How do you channel the singers on guitar?

I listened intently to the singers. I actually transcribed some of George Jones’ vocal parts—he’s the master of a very rococo style. There’s a lot of melisma, notes in between notes, and that’s what I’ve always loved about country. I wrote down the notes of the vocal parts. Then I tried to play them on guitar and just generally gave up, but went for the overall feel instead.

How so?

I found that playing lines all on one string is one way to make the guitar sound like a voice. I’ve actually been working on things like that not just for this record, but in general.

For a jazz guitarist, you pick near the bridge a lot on the album.

That’s just trying to get that sound a guitar makes. A lot of blues guys do it, and on those semi-acoustics it works better than on, say, an ES-175. Whatever sound I get on the guitar comes from just experimenting with my hands to produce different sounds. I happen to gravitate toward that certain sound you get playing close to the bridge, though lately I’ve noticed on ballads I’m picking more up toward the neck.

How did you select the songs for the record?

On this album I already knew all of the songs except for one. I could relate to all of them, and when I sat down to play the melodies and arrange them on guitar, everything unfolded naturally. The first song on the record, “Mr. Fool,” a George Jones tune, was not one I’d heard before. Larry Goldings is a fan of country and Mr. Jones, and he played the song for me. Actually, James Taylor had played it for him. And I just loved the track right away, and I knew I could arrange it and turn it into jazz like the others.

Describe the arranging process.

It wasn’t like writing big-band charts. It was, in fact, some of the easiest music I’ve worked out in a while—at least on the surface. I changed some things harmonically so the tunes would be playable with a bebop language, as well as a country language, so I could use either style to improvise. That meant recomposing the songs a little—not like changing the chord progressions to “Giant Steps” or anything like that. It’s more about putting in the occasional ii–V. I thought about that a lot: borrowing harmonically from modern jazz and putting a little of it in country. A perfect example is “Red River Valley”—a three-chord song, with basically the same harmonic structure as “When the Saints Go Marching In.” It’s the same idea that’s been done so often with the basic blues progression—putting in those passing, ii–V, and diminished chords to make it more of a vehicle for bebop improvising.

John Scofield comps behind tenor sax titan Joe Lovano at the 2016 Newport Jazz Festival. “I wanted to learn jazz as a teenager,” says Scofield, “but it didn’t happen right away. It took quite some time before I got anything together so I could play with people who knew jazz.” Photo by Douglas Mason

The album has a nice range of grooves—many of them different from the original songs. For example, you play Dolly Parton’s “Jolene” in 3/4 time.

That’s originally in 4/4, and I thought, “How would this sound as a waltz?” And then I arranged it in C minor with these kind of modal chords—a really droning thing that goes right to Coltrane land. The classic Coltrane Quartet, with McCoy Tyner on the piano, really started that style of playing. I’m really into that band and always have been.

In contrast, Hank Williams’ “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry” was originally a waltz.

We really changed “Lonesome.” First of all, like you say, it was originally a waltz and we did it in 4/4, sped it up, and played it over an augmented chord. So the basic harmonic thing is not even major or minor. I feel that the guy who invented that kind of thing is Coltrane, especially on his piece “One Down, One Up.” It’s like an encyclopedia of improvising with augmented sounds. You’re in this gravity-free zone, because there’s not a tonic in the traditional sense. I’ve been working in that area for years and trying to figure out that stuff. It’s taken a long time and there’s still a ways to go. This is actually the first time I’ve ever recorded anything like that.

John Scofield’s Gear

Guitar

• 1986 Ibanez AS200 with Voodoo Humbucker ’59 pickups

Amp

• 1964 Fender Deluxe Reverb

Strings and Picks

• Assorted D’Addario strings

• D’Addario Classic Celluloid heavy picks

You mention Coltrane—tell us more about his importance to you as a guitarist.

Because I’m a jazz player, Coltrane’s importance is paramount. He brought certain sounds to jazz and extended the idea of just playing in one key [over one chord]. He and Miles Davis started a whole style of modern jazz. These are my idols, the guys I’ve loved and studied for years and am totally indebted to.

For a jazz guitarist, you do a lot of string bending. How did you come to incorporate this technique into your playing?

A lot of jazz players don’t bend as much as rock and blues guitarists, although you hear Charlie Christian doing some bending [in the 1930s and early ’40s]. The real great bending started happening in blues music in the 1950s—players like B.B. King and Albert King were the masters, and that’s where all the rock players picked up bending from.

Post-Charlie Christian guitarists before me, like Jim Hall and Wes Montgomery, didn’t do much bending, but most people my age started learning jazz at the same time that Hendrix and Clapton were on Top of the Pops. If you wanted to learn to play guitar in 1967 when I was a kid, the blues was it. So I started as a blues guitarist, but when I heard Jim Hall and Wes Montgomery, I wanted to be a jazz guy.

Nowadays, it’s funny—and so separate. If you want to be a jazz guy, you’ll probably get a box with flatwound strings and play in that jazz-guitar tradition. But in the ’70s when I put my style together, it seemed appropriate to do what I’m doing. It’s idiosyncratic, and I guess that’s a good thing [laughs].

It’s a very good thing. Was there a particular moment at which you began to identify as a jazz guitarist?

I wanted to learn jazz as a teenager, but it didn’t happen right away. When you’re a kid and you learn about the pentatonic blues scale, you’re a bluesman within a couple weeks. You might not be very good, but you feel like a bluesman. When I was about 16, I decided I wanted to be a musician, because I definitely didn’t want to be a businessman like my father and do the 9-to-5 thing. I wanted to be a musician because that was way better than the mind-numbing thing that most people did. So I set my eyes on being a musician. I thought, rock ’n’ roll is great, but I’m not going to be like Jimi Hendrix—a front man singing and playing guitar behind his back. I can’t do that and don’t have the balls to.

At the same time I started getting into jazz recordings and thinking, “This is different; this is deep. Maybe I can get a handle on it if I just practice a lot.” It took quite some time before I got anything together so I could play with people who knew jazz. I remember the first year I went to Berklee College of Music. I was 18 and it was the first time I was around people who could actually play. Before that, I had my Coltrane records, but living in suburban Connecticut, none of my friends could play jazz. I had one friend to jam with, but I don’t think we played jazz. During that first year at Berklee, I just practiced my ass off, and at the end of the year I started to say, “I’m a jazz guitar player.” I wasn’t very good, but I could play a few tunes.

Tell us about the group you recorded the new album with.

For me, this is a dream team. I’ve played with these guys for so many years. Steve Swallow was my teacher in the early 1970s—we met at Berklee and have played together ever since. I met Bill Stewart in 1989 and we’ve been playing together a lot since. Shortly after that, in the early ’90s, I met Larry Goldings and we’ve also worked together a lot. So these are old friends and my closest musical associates—guys I don’t have to talk with about the music we play together. The music seems to unfurl before it happens. I put the band together with the project in mind and couldn’t have done the record with any other ensemble. At first I thought to go to Tennessee and record it with some Nashville guys, but it made the most sense to do something both country and jazz, and this band of jazz players, who all happen to love country, just nailed it.

You produced the album. What was that like?

Producing a jazz record—not to take away anything from a good producer—wasn’t all that difficult. I knew how to do what we wanted to do, knew not to get in the way of the other musicians, and that the music would evolve naturally. Once we were in the studio, the engineer Jay Newland and Brian Bacchus, one of the guys from the record label, were there to bounce ideas off, and certainly the other musicians helped me. But really it was pretty straightforward: I picked the tunes that went together nicely to create enough different moods for a good album, and then we just went in and did it.

Was the music pretty much played live in the studio?

Not pretty much—it’s all played live. There’s one song where Larry overdubbed a pass of organ over the piano, but all the solos and everything were absolutely live.

As it should be.

I guess for jazz it should be. It’s wonderful to sculpt a piece of art using all of the recording techniques that are available. But as a jazz group, I really wanted to capture that live vibe because anything else would feel like cheating. If I were to change my solos after the fact, what the rhythm section played wouldn’t be related to my solos. The rhythm section isn’t just playing a beat; it’s responding to what I’m doing. So it wouldn’t have sounded as good. The responses from the rhythm section are really important.

Earlier you mentioned having your wife as a business partner. What’s it been like to make a living as a jazz musician?

I’ve been lucky, man. I’ve been in the right place at the right time and can’t believe I’ve had this wonderful middle-class existence. I live in a nice house and sent two kids to college, all from playing jazz or jazz-related music. I never thought I would do this well. I thought I would just be giving guitar lessons and playing when I could.

When I started, the scene was different than it is now. There were lots more opportunities to play gigs that would pay the rent. But there’s still a music scene, and there are opportunities. As a jazz guitarist, you might find yourself playing music outside of jazz, but that’s a good thing, because I think you learn a lot from any musical situation you’re in—even one where you might not love the music. I’ve always walked away from that stuff with a little bit of a broadened approach. It’s good to get out there, folks. It’s good to leave the practice room and get out into the real world!

YouTube It

Here’s a neat glimpse of John Scofield in the studio, recording the tune “Bartender’s Blues” for Country for Old Men.

Play It

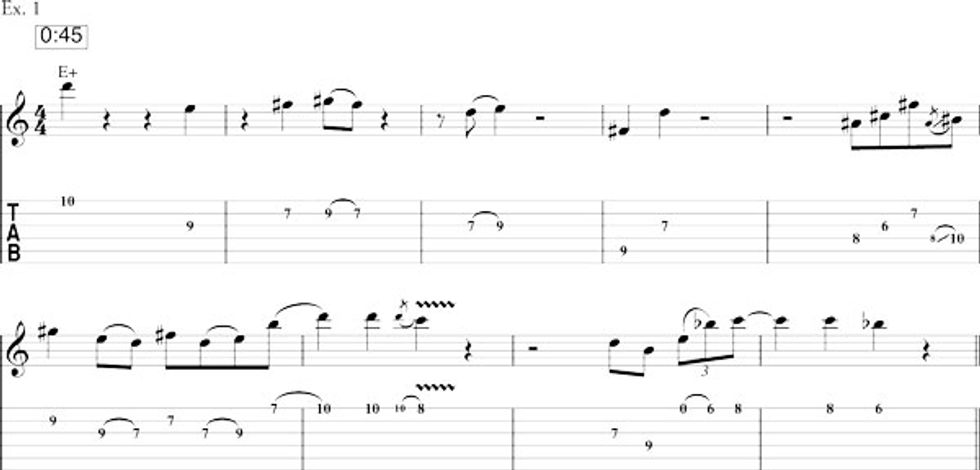

On Country for Old Men,John Scofield reworks the Hank Williams classic “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry” into an augmented tour de force, as illustrated in Ex. 1. The E augmented chord (E–G#–C) is found within the E whole-tone scale (E F# G# A# C D), and Scofield deploys the whole-tone scale here to smart effect. Note the judicious use of space. Instead of blowing endless streams of notes, he uses rests to create dramatic tension.

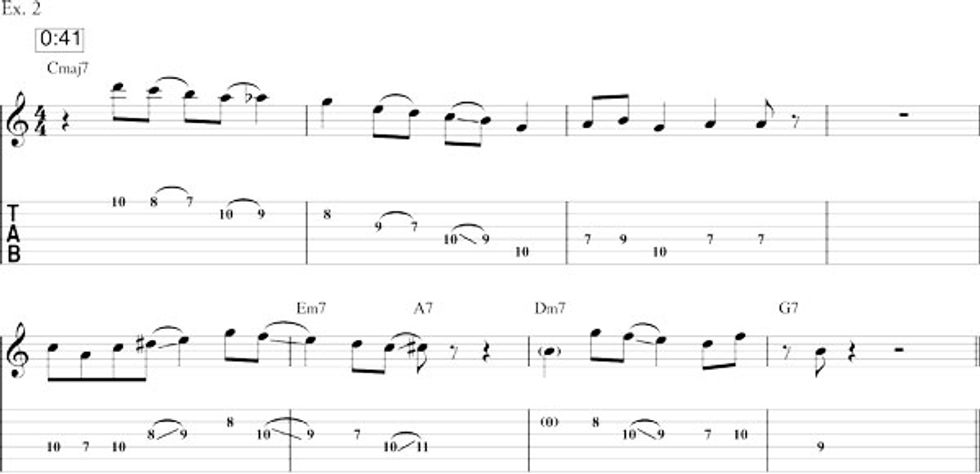

Even when he sticks more closely to the original composition, as in “Red River Valley,” (Ex. 2), Scofield tends to improvise in a way that’s less country than jazz. The beginning phrase here is classic bebop vocabulary, and the chromatic passing tone that bridges the notes A and G in measures 1 and 2, and half-step approach tones into E in measures 5 and 6, add important color. Sco also finds nooks and crannies for inserting ii–V lines. Check out the pair of ii–Vs, Em7–A7 and Dm7–G7, that close out this example.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)