In the beginning, everybody building gear wanted a purity of signal. Pickups and amps were designed to eliminate distortion and leave the natural sound of strings and wood uncolored. Les Paul himself felt like the P-90 pickup in his signature guitar was too prone to overdrive, so he stuck a DeArmond pickup in the neck of his No. 1 until Seth Lover came to him with the ultra-pure alnico V, Gibson's “staple pickup," in 1953. Then something unexpected happened. When guitar players cranked up their amps to be heard over the crowd, the musicians and the audience were seduced by the distortion that engineers were trying to avoid.

My friend Jason Dunaway, a bassist I've played with for years, also happens to be an electrical engineer who's helped design some of the gear many of us have used at one time or another. A little over a decade ago, I was writing a Premier Guitar feature called "Cult of Tone," where we examined the elements that shape guitarists' worldviews and define what they view as their Holy Grail of Tone. I asked Dunaway for a scientific explanation of why we're drawn to overdrive.

"Our ears/brains are really amazing," Dunaway said. "We can divine an incredible amount of information very quickly by listening. Is it a real cry or are they just messing around?" In short, our hearing has an amazingly difficult job of picking up the tiniest nuance in sound and processing the information: sarcasm, deceit, urgency, playfulness, anger. Some 100 million years of evolution developed these abilities—our ancestors' hearing had to be good to ensure survival of the species. So how does this relate to our choice in guitar tone? It goes back to survival.

"Generally when we're stressed or excited and want to verbally express it, we go up in volume and drive our vocal apparatus harder than normal," Dunaway continued. "Things get nonlinear and our normally smooth voices have more high-frequency content and volume than normal. Over time, we have come to perceive this changed harmonic content and increased volume as something that needs to have our attention. It may be danger, it may be an opportunity ... but whatever it is, it excites us. It also says 'Listen to me! Ignore all that other stuff that's going on.'

"I once had a door chime that was the actual recording of Zeppelin's 'Black Dog'—for one day. Every time someone rang the doorbell, it scared the shit out of me!"

"We find even-order distortion fairly pleasing. That's essentially the addition of stacked octaves on top of the fundamental tone, and is a result of asymmetrical distortion [one side of a waveform clipped more than the other]. Odd-order distortion gives us odd multiples of the fundamental, which is not very musically pleasing. (Example: symmetrically clipping an op-amp.) Where does every guitar/saxophone/vocal solo or evangelical preacher go to bring the crowd to their feet? Loud, high, and way nonlinear. A scream has much more high-frequency content than a normal speaking voice, regardless of volume."

The reason the hair stands up on your arms when you hear a Les Paul ripping through a warm, fat, tube amp is because your body has evolved over millions of years to respond to those nonlinear waves. Our bodies tell us that these sounds are important and we feel physically excited when we hear them. Conversely, these tones don't always bode well in an everyday context, as Jason learned from personal experience. "Tones that are used for everyday signaling like a doorbell are pretty simple. They don't alarm us too much. I once had a door chime that was the actual recording of Zeppelin's "Black Dog"—for one day. Every time someone rang the doorbell, it scared the shit out of me!"

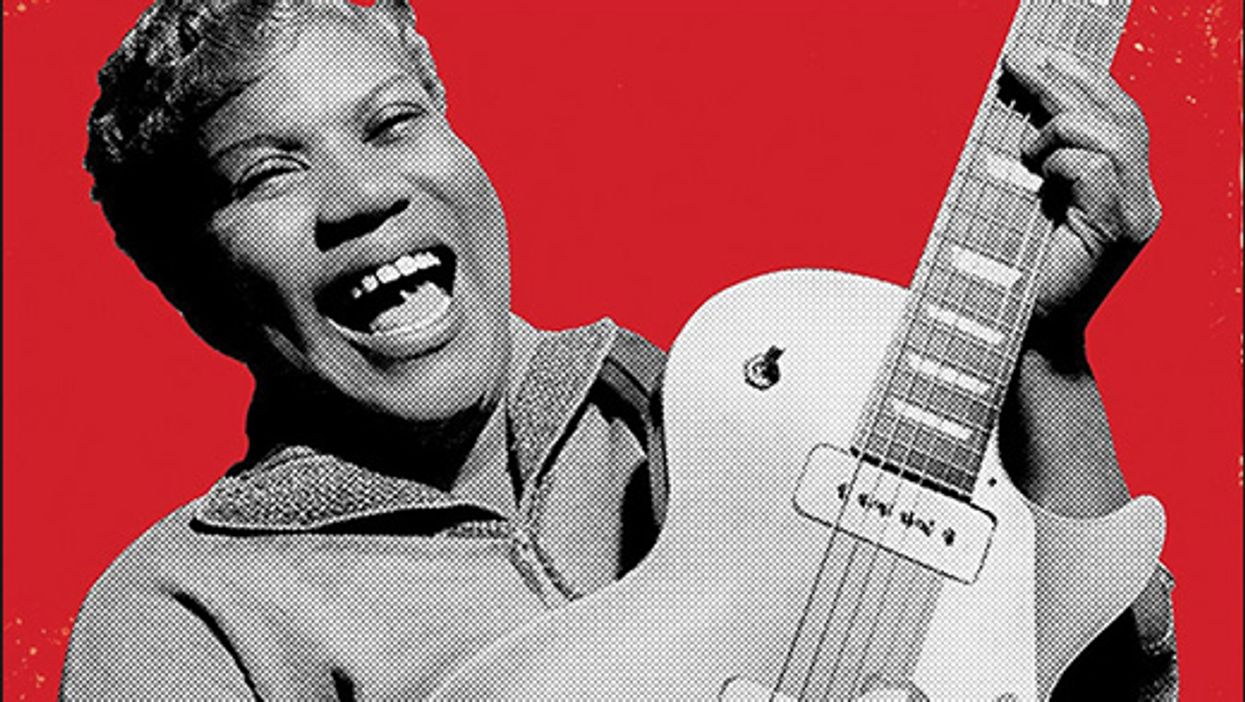

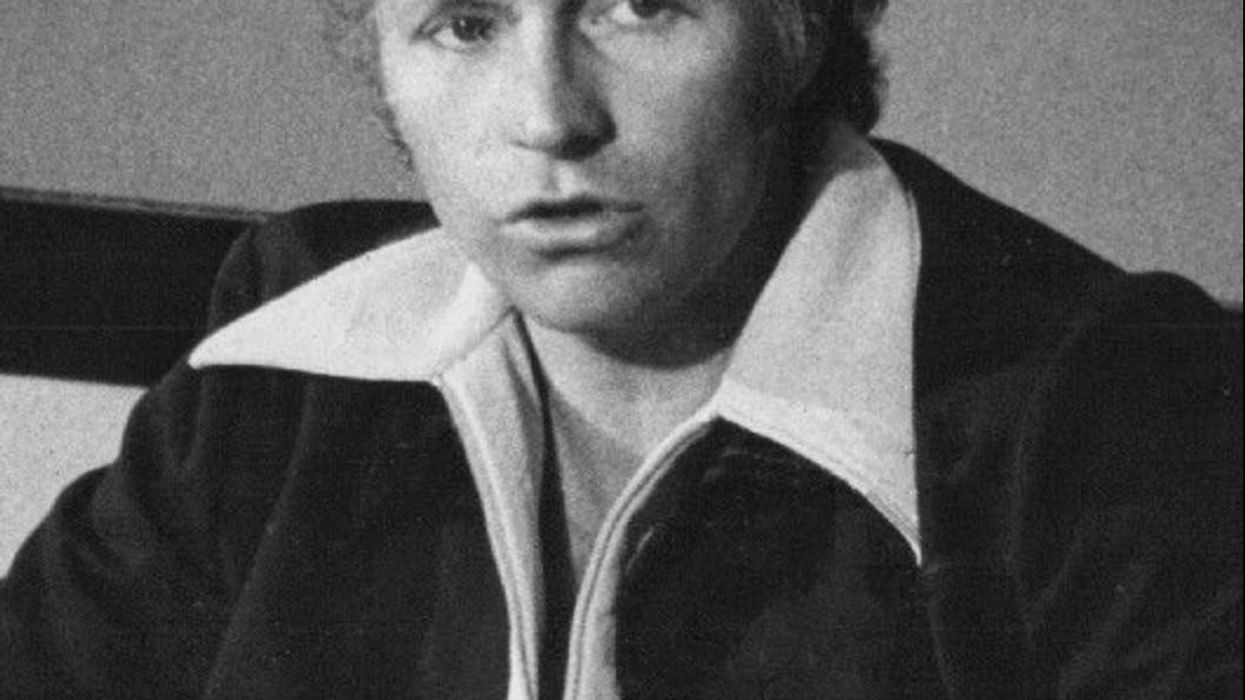

We're physically built to respond to certain tones, which helps explain why masterful musicians use tone to evoke an emotional response. For the most part, my default mood is up. Perhaps that's why I lean toward the clean tones, but there are times when the only way I can express what I'm feeling is to turn all knobs right and howl. Listen to the way Sister Rosetta Tharpe used overdrive with both her voice and her guitar playing to get the crowd fired up.

Had Sister Rosetta kept it clean, her songs might've sounded like nursery rhymes. Her use of drive connects to the audience on a primitive level that goes beyond the lyrics and melody.

The nuance of sound quite literally has a power over us. And that gives sound an almost mystical quality. This invisible force can make us happy, horny, sleepy, angry, sad, excited, worried, etc. Sure, there are scientific reasons why guitars make us feel the way they do, but what fun is that? Let miracles be miracles. Music, like prayer, is our primitive attempt at expressing the ineffable: It's not so much what is said, but how you heard it.

Sister Rosetta Tharpe - Up Above My Head on Gospel Time TV show

[Updated 8/16/21]