Intermediate

Intermediate

• Learn all about guide tones.

• Apply simple theoretical concepts to give your blues playing more harmonic definition.

• Build on the supplied harmonic and rhythmic examples to hot-rod your own solos.

It’s easy to just live inside a single pentatonic or blues scale over an entire 12-bar progression, but how hip is it when you hear players really get inside those chord changes? In this lesson we’ll explore some simple techniques that will allow you to create solos that lead the ear through the progression. The goal? To be able to take a cohesive solo that outlines the changes without another instrument providing the harmonic foundation.

Now, we aren’t immediately jumping into Joe Pass territory here. I want to share some techniques to build your confidence, so let’s start with just two notes to demonstrate how easy it is to outline the sound of a chord.

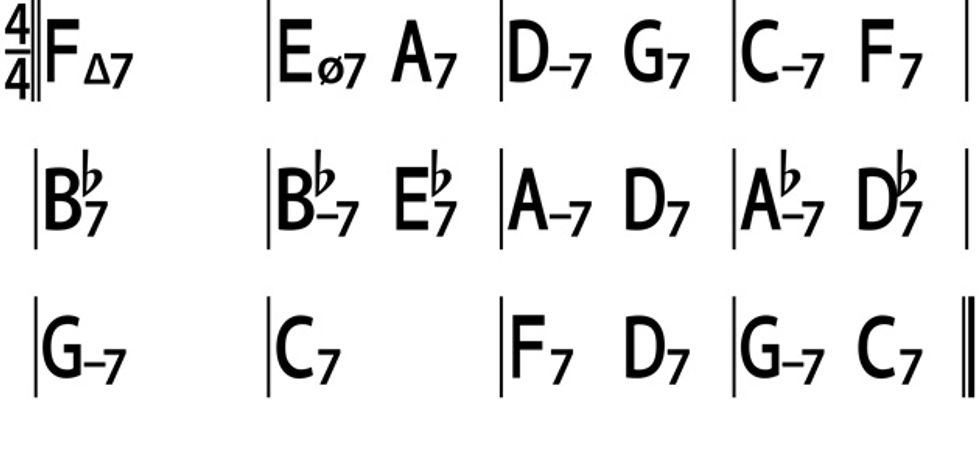

As promised, Ex. 1 only deals with two notes—the 3 and the 7 of each chord. For all our solos, we’ll use a guitar-friendly 12-bar blues progression in the key of G. The first step it to outline the target notes for each chord. Because these are all dominant 7 chords—which have a formula of 1–3–5–b7—we’ll lower the 7 by a half-step:

- G7 – B and F

- C7 – E and Bb

- D7 – F# and C

Ex. 1

We’ll add the root into the mix for our next solo (Ex. 2). You can see how we’re now building on the previous example by adding more color to the canvas. I should also mention that my 16th-notes have a swing feel. This adds some bounce. I’m also doing some large interval leaping within the chord changes, which creates a cool call-and-response effect.

Ex. 2

You might be able to guess what’s next. Yes—it’s time to add the 5 of each chord to our pool of options. Now we have the full four-note arpeggio available to us:

- G7: G–B–D–F

- C7: C–E–G–Bb

- D7: D–F#–A–C

Ex. 3

In Ex. 4, we expand our note choices to include the 6, or 13. Since we’re dealing with dominant chords, which contain a b7, I prefer to call them 13. But that’s just theory mumbo-jumbo. [Editor’s note: When constructing chords that use tones other than the 1, 3, 5, and 7 of a standard “7th chord,” the color note in question can occur in the same octave as the root, or an octave above the root. The latter are technically termed “extended chords” because they reach beyond the 7 into the next octave. These include 9, 11, and 13 chords that can be major, minor, or dominant, depending on what type of 3 and 7 they contain. Just remember this: Whenever you see a number greater than 7, simply subtract 7 from it and you’ll get the scale degree in the same octave as the root. That’s the color note you’re dealing with. In this case, 13 - 7 = 6. So in the chord spelling below, this note appears as the 6, even though you might actually play it an octave higher than the root as a 13.]

Here’s what we have now:

- G7: G–B–D–E–F

- C7: C–E–G–A–Bb

- D7: D–F#–A–B–C

Ex. 4

Next up, we add the 9 to each chord. [Remember our “subtract 7” formula: 9 - 7 = 2. So in the chord spellings below, the color note in question is shown as a 2, though you’ll often play it an octave higher as a 9. Same scale tone, different octave.] This is a common note to add to not only dominant chords, but major and minor chords, too.

Here’s where we’re at:

- G7: G–A–B–D–E–F

- C7: C–D–E–G–A–Bb

- D7: D–E–F#–A–B–C

Ex. 5

Our final piece of the puzzle is to add the 11, or 4, to the mix. [Once again, our “subtract 7” formula comes into play: 11 - 7 = 4.] We now have progressed from the bare-bones guide tones—3 and b7—all the way through arpeggios and landed on the full Mixolydian mode for each chord.

- G7: G–A–B–C–D–E–F

- C7: C–D–E–F–G–A–Bb

- D7: D–E–F#–G–A–B–C

Ex. 6

In closing, I want to leave you with a thought about the rhythms I used throughout the examples. A good sense of rhythm and a depth of rhythmic ideas are as essential to great soloing as your harmonic chops. Rhythm and harmony are equal partners. Make sure you work on both!