When I was younger, I didn't handle mistakes well. Every time I hit an unintentionally ugly note at a gig, session, or jam, I would be so preoccupied with self-loathing and shame that I would consistently follow that clam with two, three, or seven additional flubs. I focused on my clams, not the music, which killed the fun factor. Worse yet, because I could not get past the past, I played scared. So even if I was hitting the right notes, they didn't sound right. Those performances were the sonic equivalent of Barney Fife law enforcement.

Today, when I blunder during a live performance, I try to leave my errors behind me like a John Woo film—cars and buildings exploding in the background as I slowly walk away with my Wayfarers pointed straight ahead, never looking back. I'd rather be strong and wrong than timid and technically right. This isn't just my personal battle cry—this is a universal truth set in stone four decades ago by the two Jims: Hendrix and Page.

Google “Best Guitar Solos Ever" and “Worst Guitar Solos Ever" and you'll find Jimmy and Jimi on both lists. Page's “Heartbreaker" solo gets referenced on both all the time. It's an epic performance, but you'll never convince me Page's fingers were doing exactly what he wanted them to do for every note of his herky-jerky, dweedly-dweedly guitar wizardry.

The same could be said for the “Black Dog" bridge. Page plays it differently every time—a little rushy/draggy/wonky, it's the sonic equivalent of watching a cat fall off a ledge, then right itself at the last millisecond to land safely on its feet. These examples of Page's playing remain timeless … in more ways than one.

Some argue Page made a lot of mistakes on those classic records, but when it comes to recordings, Page, like a lot of other legendary musicians, played like Jackson Pollock painted. Colors splattered chaotically can carry a lot of emotional weight in their randomness and slop. Page heard several takes of those songs and chose the versions that got his message across best. The unwritten rule remains that once artists sign off on their work, terms like “mistake" are irrelevant. It's either art you like or don't; any rule breaking is applied artistic license. Artistic license is that empowering phrase that makes a G–C–F–Bb quartal cluster sweet like monkey meat. Great news if you're an artist—not so great if you're a musician working on somebody else's art.

that will work.

If your job is to play music for somebody else's project, then, technically, it's a mistake whenever you veer away from what the leader wants. That's why Hendrix was fired from his first gig before the second set and why, later on, Little Richard and Ike Turner canned him mid-tour. He was discharged for playing like Hendrix. Jimi was an artist who couldn't compromise his work, so him playing with Little Richard was a bit like hiring Picasso to paint your kitchen eggshell white. (Taking nothing away from the fabulous L.R., but “Tutti Frutti" is not “Castles Made of Sand.") The world is lucky Jimi followed his muse rather than tamed it to fit in as a sideman, though being a sideman can be creative and rewarding work.

Professionally speaking, I'm a sideman. Most of my work is attempting to play what other people want for their music. I try to avoid mistakes so people will continue hiring me, but I don't get too rattled when my fingers make me sound like I'm playing with my toes as they stumble a fret up or down from where I want them.

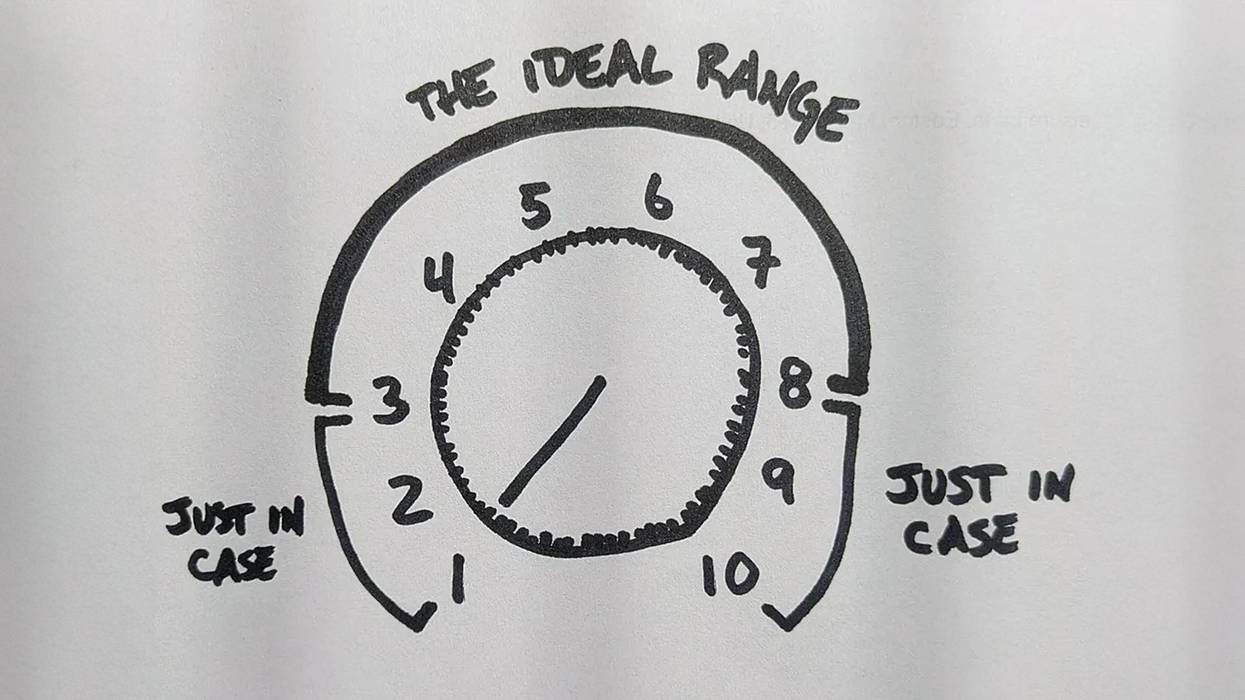

The advice of Joe Pass helped me become a bit more Zen about those color tones. Pass said, “If you hit a wrong note, then make it right by what you play afterwards." On guitar, you're never more than one fret away from something that will work. An errant note can easily become a glissando into the melody, making that slip the coolest thing played in the entire song.

As musicians, we spend a lot of time learning patterns, which makes our playing grow stale. Eric Johnson said, “My best songs come from making a lot of mistakes and playing a lot of garbage." What some people call mistakes are really just a scenic route to new musical territory. Playing what you didn't mean to play is an opportunity for something awesome that's never happened before. In a homogeneous world where the majority of recordings are quantized and autotuned, the unexpected is a gift.

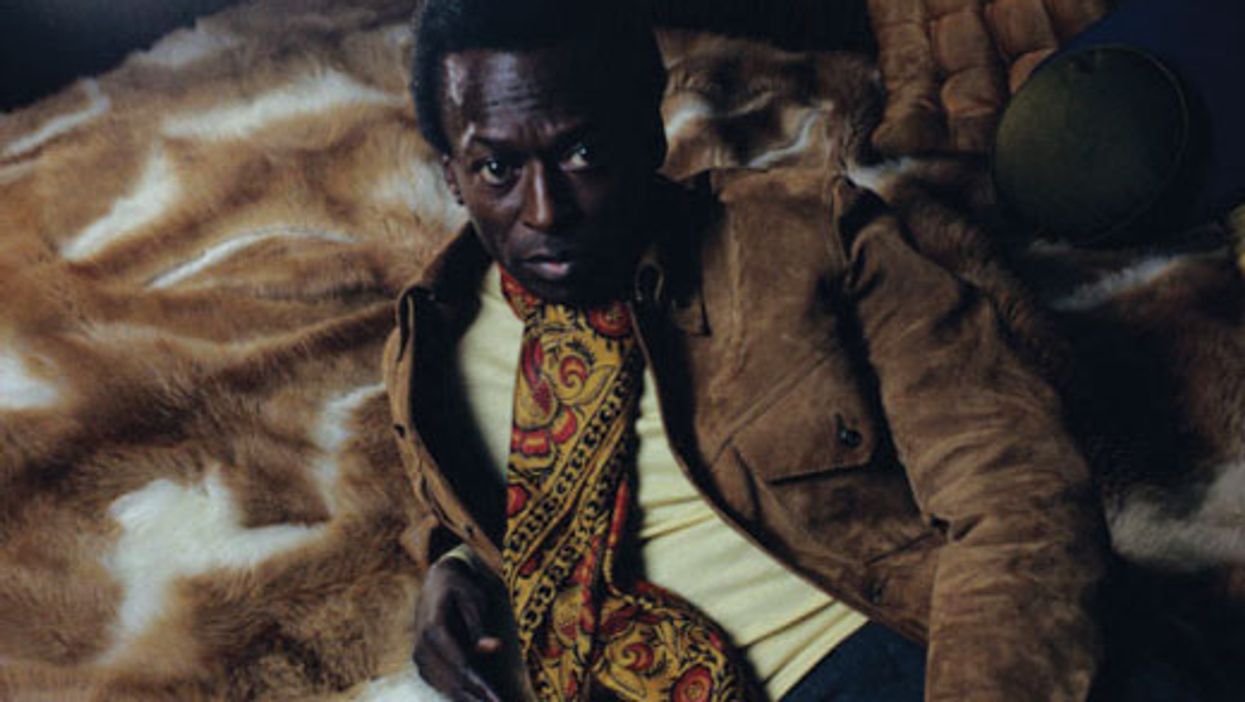

In music and in life, missteps are often the best part. When I was in college and my girlfriend told me she was pregnant, I thought, “Colossal mistake, my life is ruined." Turns out, the whole parenthood gig was the best thing that ever happened to me. There are endless examples of wrong turns leading us right where we need to be. (This is the part where I repeat the title to really drive home the message.) Miles Davis said, “Do not fear mistakes. There are none." That totally takes the pressure off. Enjoy the stumble.