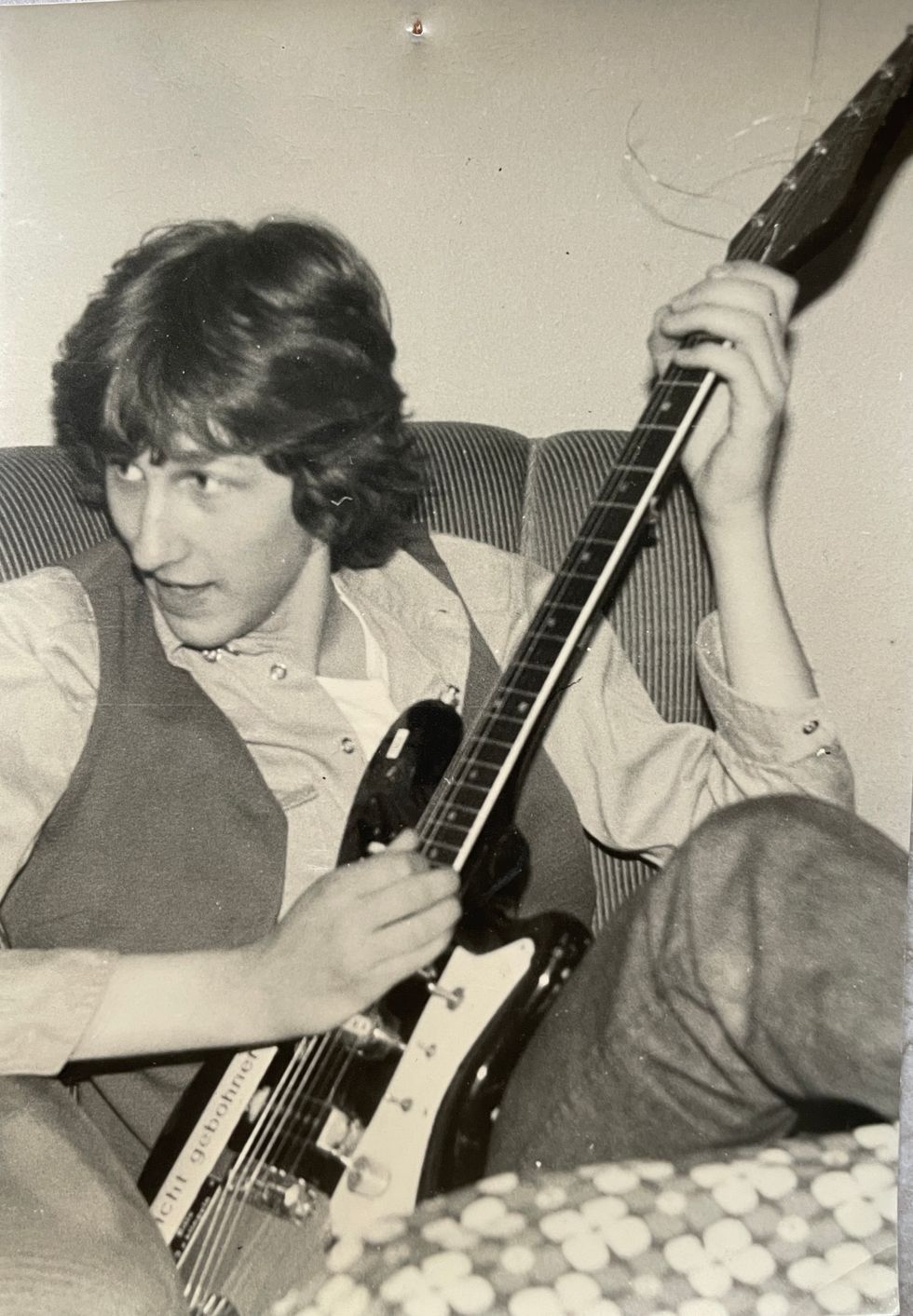

To this day, when I'm not touring and get a call to play, I drive downtown, spend too much on inconvenient parking, and schlep my gear three-to-five-blocks to slog through cover songs for a four-hour, break-free set. Then, at the end of the gig, the band huddles around like pirates and splits the tips and subtracts the bar tabs. By then it's 2:45 a.m. and I'm exhausted as I lug my gear back to my car through a maze of drunks. I've usually earned somewhere between $4 to $25 per hour in sweaty bills. Why would anybody play these shit gigs, you ask? Because, as 1977 Fleetwood Mac said, “players only love you when they're playing." Birds gotta fly, fish gotta swim, players gotta play. Playing music is an addiction. There's no 12-step program. We chase the dragon.

Up until recently, every time I loaded into Tootsies, Layla's, or Robert's, I'd see Mandolin Mike Slusser, bathed in flashing neon light, playing his old battered F-style mandolin and singing with thick veins bulging out of his red neck. It might be 105 degrees in July and Mike would be there in full cowboy regalia: 10-gallon Stetson, old-timey vest, pressed button-down shirt, boots, jeans, big belt buckle—rendering everything from bluegrass to metal for passersby.

It might be 10 degrees and snowing and he'd be out there beating that mando like it owed him money, fingers burning red on his sledgehammer right hand. He told me once he was playing outside in freezing weather and nobody would stop and listen. He just kept getting more and more pissed off as people raced by him with their collars turned up, ignoring him as they ran to their destinations. This anger fueled the fire to keep playing longer and harder until it was just him and the snow flurries. When he finally tapped out, his hands swelled in knots.

When I played solo gigs at Henry's Coffeehouse, Mike would walk in and drop a dollar in my tip jar. On my way out I'd drop it back in his mando case. We passed the same crumpled bill back and forth for years, like a sacred good luck offering.

Mike arrived in town two or three years after I did. He told me that since then he'd logged roughly 26,000 hours playing on that block but his F-5 mandolin does not look a day over 23,000. I've never met a more dedicated musician.

At one point, Mando Mike and I lived parallel lives. We had roughly an equal amount of talent, which drove us to area code 615 around the same time. Once arriving, we spent some desperate times living in our cars, playing in terrible/good bands in crap bars, eventually booking some sessions, TV, etc. But for the most part, just playing every chance we got. The last time I saw Mike, we stood on the street and talked about our crazy career odyssey.

Mike summed it up: “Man, we moved here to become Nashville Cats, and now we are. It may not be like we imagined it, but nobody's going to argue the point."

In May of last year, Mike split. I'm told he moved back to Pennsylvania to look after his ailing parents. The news left me grateful/sad, weeping/giggling/wanting-to-get-drunk-or-stoned. For roughly 18 years, that guy took no sick days, never missed an opportunity to perform, and remained absolutely devoted to his music. When he wasn't performing, he was learning songs in preparation for his marathon show. It's off-putting to see Sisyphus walk away from his boulder.

I'm not more talented and definitely not as dedicated as Mike, but to the outside observer, it would appear that I've had more success than him. That probably comes down to that fact that Mike flew solo while I had a wife and kid, which made money waaaaaay more important to me. Though Mike and I both struggled financially (my apologies to Former Wife #1), I had to look for opportunities that would lead to a regular paycheck, whereas Mike just stuck to what he knew: playing and singing on the street or in a club. Mike was pretty Zen about life, whereas I was terrified of not being able to provide for dependents.

Mike pursued his art and enjoyed a freedom that few experience. His career makes you reassess. What is success? Doing what you love sounds about as successful as it gets.

Wherever you are Mike, I know you're playing music for people. (If you read this, let me know where you are. I would love to hang!) I'm not worried about you, but I don't think that mandolin is going to make it. It's, like, one song away from becoming a pile of toothpicks. Play on.