Sad songs make me happy, like drinking makes me thirsty.

It's an odd paradox, but sitting in my car, staring dead-eyed into space and sobbing like my dog just died, while listening to heart-crushing music remains one of my favorite activities. Strange, perhaps, but not uncommon.

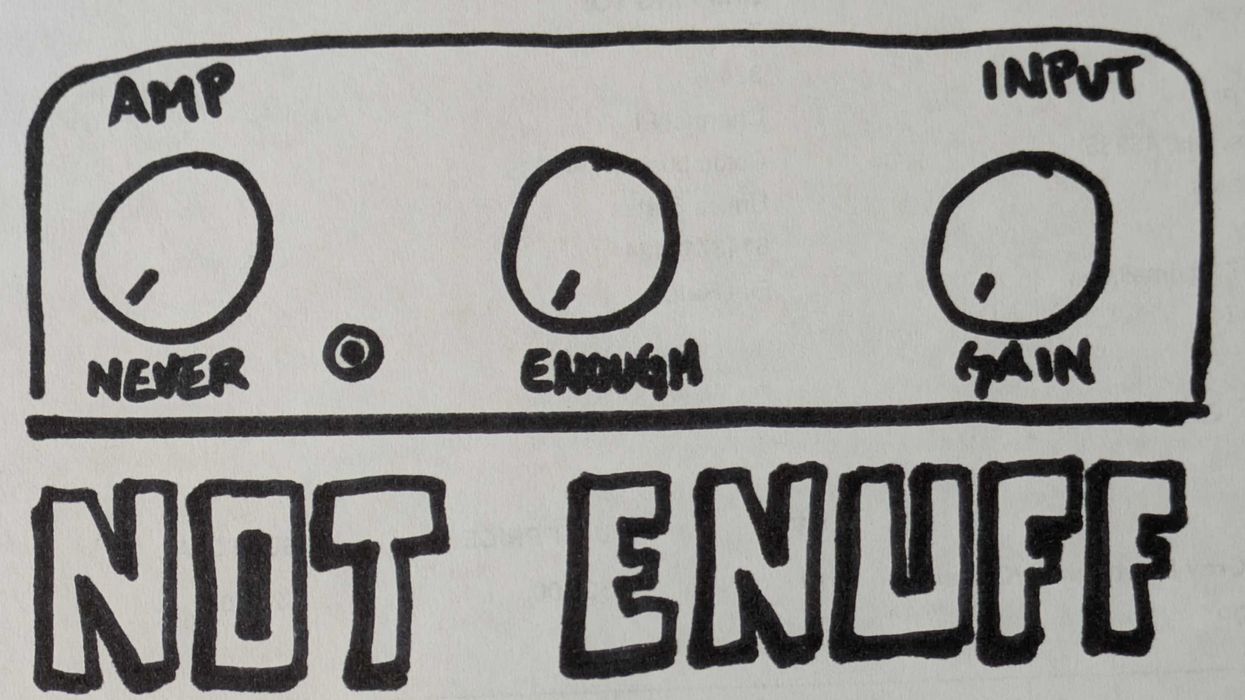

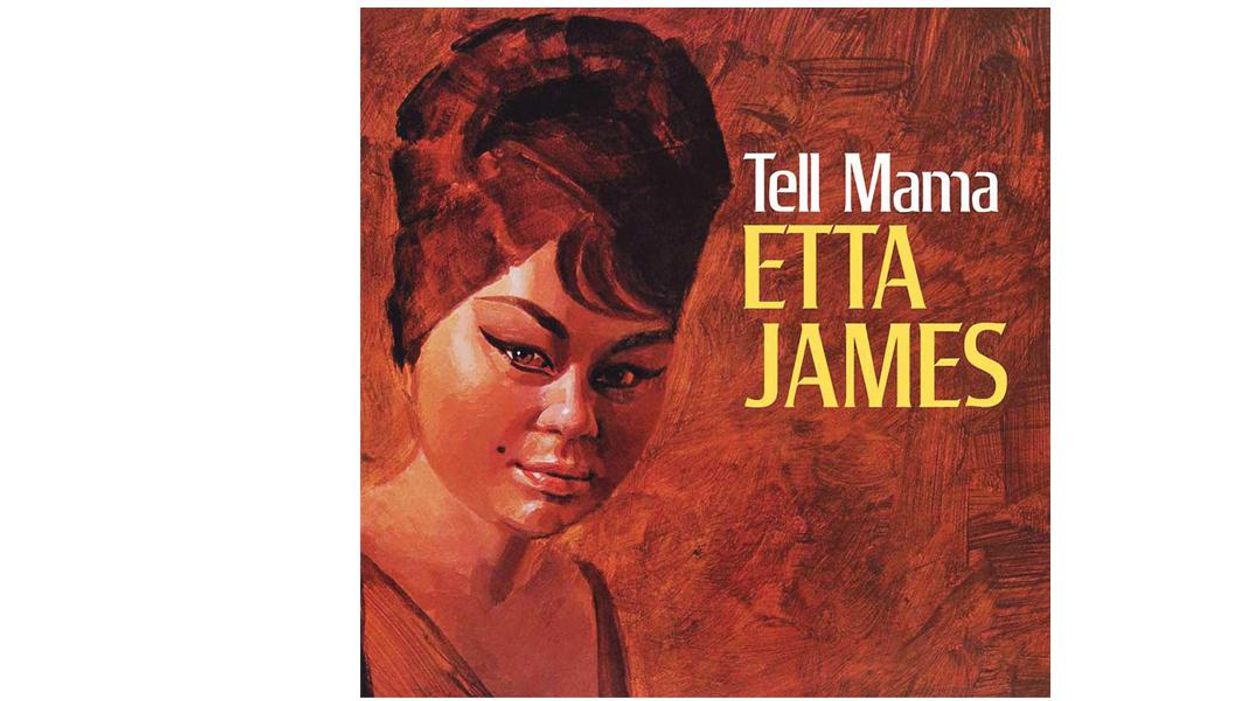

In real life, I go to great lengths to avoid hardship. When I greet someone, I rarely ask, "How are you doing?" for fear that the person will actually tell me, and it's going to be bad news. There's an unwritten law that we keep our depressing bits to ourselves or risk becoming a pariah, seen as an emotional vampire, greeting all with two armfuls of gloom and despair. Try talking to me about your horrible relationship and I will extricate myself from that pity party ASAP.Por ejemplo, if Etta James walked up to me and said:

"Something told me it was over

When I saw you and her talking

Something deep down in my soul said, 'Cry, girl'

When I saw you and that girl walking around."

I would say, "Sorry to hear that Etta, but excuse me, I have to leave now to do anything but listen to this." But when she wraps those sad words in a melody, I can't get enough of that devastation. I hang on every heart-wrenching word. Why? Well, science has a few ideas about what's going on here.

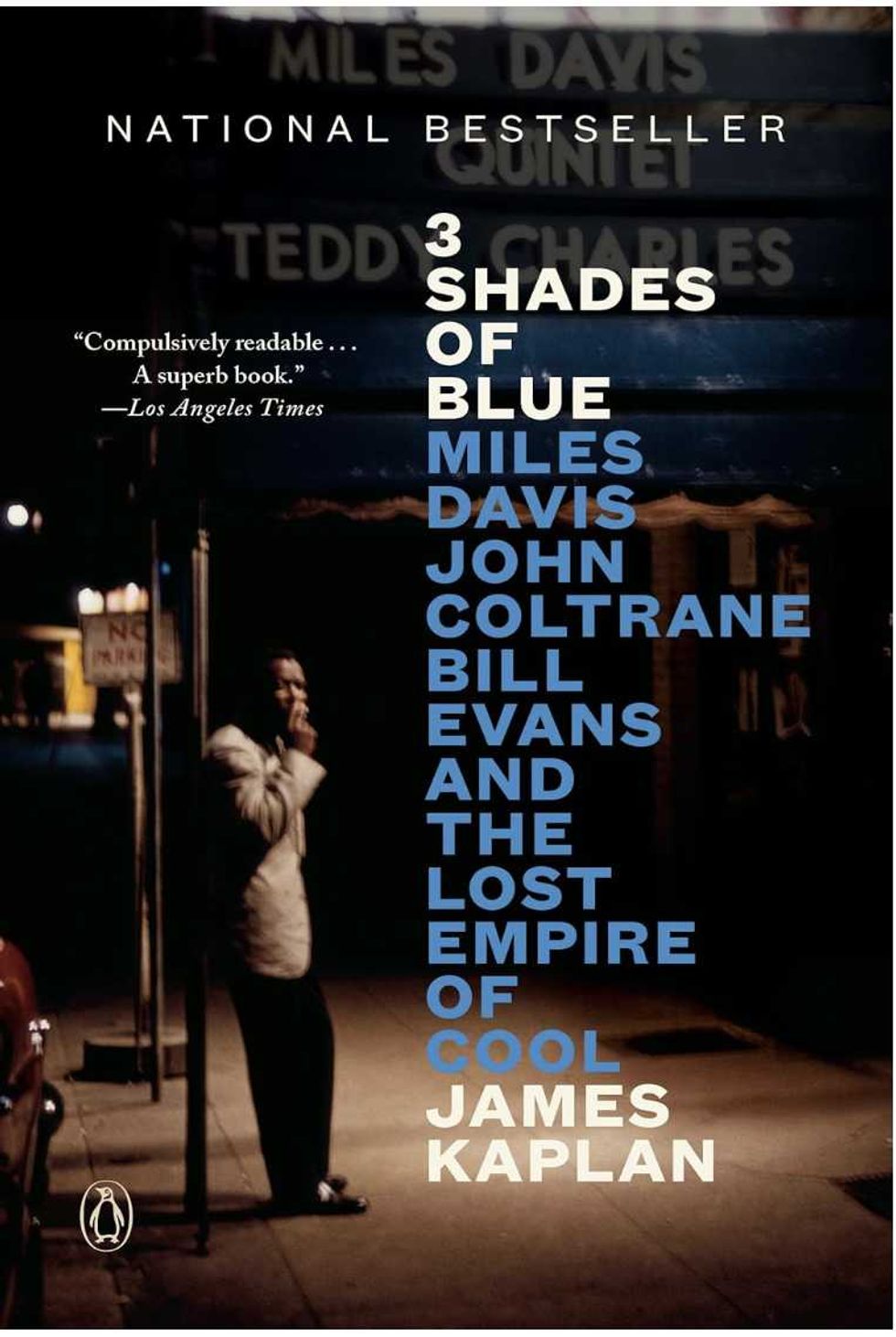

Generally speaking, minor-key music feels sad while music in a major key feels happy. We've all heard exceptions to the rule. Henry Mancini's "Moon River" is in a major key, but feels wistful, whereas Van Morrison's "Moon Dance" is minor but feels like a happy, playful romp. But, for the most part, when you flat that 3rd, 6th and 7th, it's going to feel melancholy. Scientific studies back that up, according to Popular Science, and studies also suggest that even though minor-key music sounds sadder than major-key music, most people, somewhat surprisingly, find minor key music more likable.

There's an unwritten law that we keep our depressing bits to ourselves or risk becoming a pariah, seen as an emotional vampire, greeting all with two armfuls of gloom and despair.

Some scientists hypothesize that people enjoy the vicarious sadness of a sad song almost the way they enjoy a scary movie. Since it's not happening to us in that moment, we can just sit back and observe someone else's heartbreak. But that sounds a bit sadistic to me. I can't believe that non-sociopaths take pleasure in the suffering of others. There's got to be more to it.

I'm more swayed by studies that suggest that sad music hits us differently on a chemical level. Ultimately, everything we feel comes down to our body's chemistry. An article I found from Science Alert explains it this way: "Some scientists think melancholy music is linked to the hormone prolactin, a chemical which helps to curb grief. The body is essentially preparing itself to adapt to a traumatic event, and when that event doesn't happen, the body is left with a pleasurable mix of opiates with nowhere else to go. Thanks to brain scans, we know that listening to music releases dopamine—a neurotransmitter associated with food, sex, and drugs—at certain emotional peaks, and it's also possible that this is where we get the pleasure from listening to sad tunes."

In summary, whereas all good music gives us a hit of the feel-good neurotransmitter dopamine, sad songs also give us an opiate kicker for a super-double chemical buzz. That could explain why just listening for a few minutes feels like a gut punch followed by a loving, warm hug.

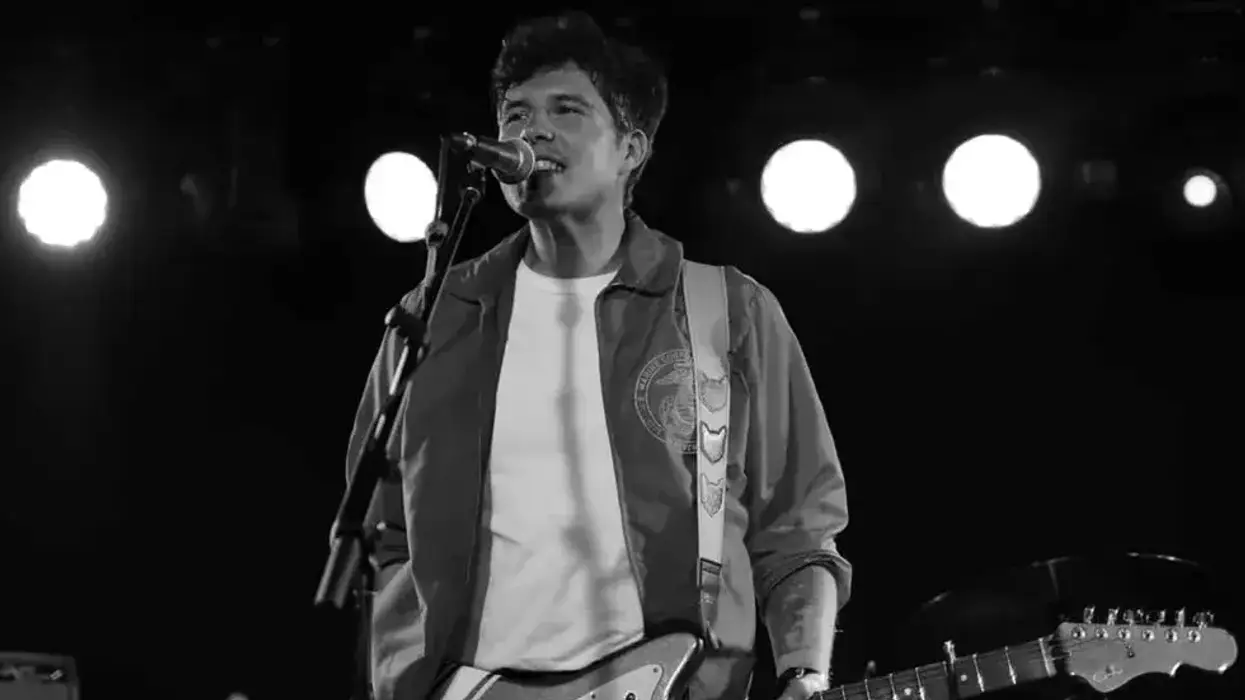

A few years ago, I was playing a songwriting festival in Crested Butte, Colorado. I stumbled into a bar, as is my custom, and found some songwriter friends in a circle by the fire passing a guitar around. My friends, recognizing me as one who is easily duped, asked me to join the circle, then had me sit to the left of Hall of Fame writer Dean Dillon. Nobody there wanted to follow Dean. I had to play one of my songs right after the guy who wrote "Tennessee Whiskey" and dozens of other iconic No. 1 songs. Dean prefaced his songs with a story of heartache that led him to write "Easy Come, Easy Go." I said, "Yeah, but Dean, it's hard to feel too bad for you, because you turn all that pain into songs, and those songs have made you fabulously wealthy." Dean paused for a beat, then replied, "Yeah, but it still hurts…. That's why I try to co-write with people going through a divorce. They've got all the good pain.

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)