It can be hard to find something that lifts your spirits up during a global pandemic. For rock-music fans daydreaming of times when live music was an option in our daily lives, a dystopian-themed, futuristic sci-fi double album from the Smashing Pumpkins really is good news for people who love good news. Cyr was released at the end of November, but an even sweeter announcement came a month prior, on the 25th anniversary of the 1995 masterpiece Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness, when the band announced that a 33-song sequel was in the works, to finally complete the intended trilogy sequence of Mellon Collie and Machina.

Pumpkins’ maestro and principal songwriter Billy Corgan, a man notoriously known for his ambition, is doubling and tripling down on his prolific nature and is downright ferocious with creating as much art as is humanly possible in 2020. “I’ve been writing a book for years,” Corgan says when he pops up on Zoom for this interview, hurriedly eating a snack. “I get up early and write the book, and I just literally finished writing, so I’m trying to scramble.”

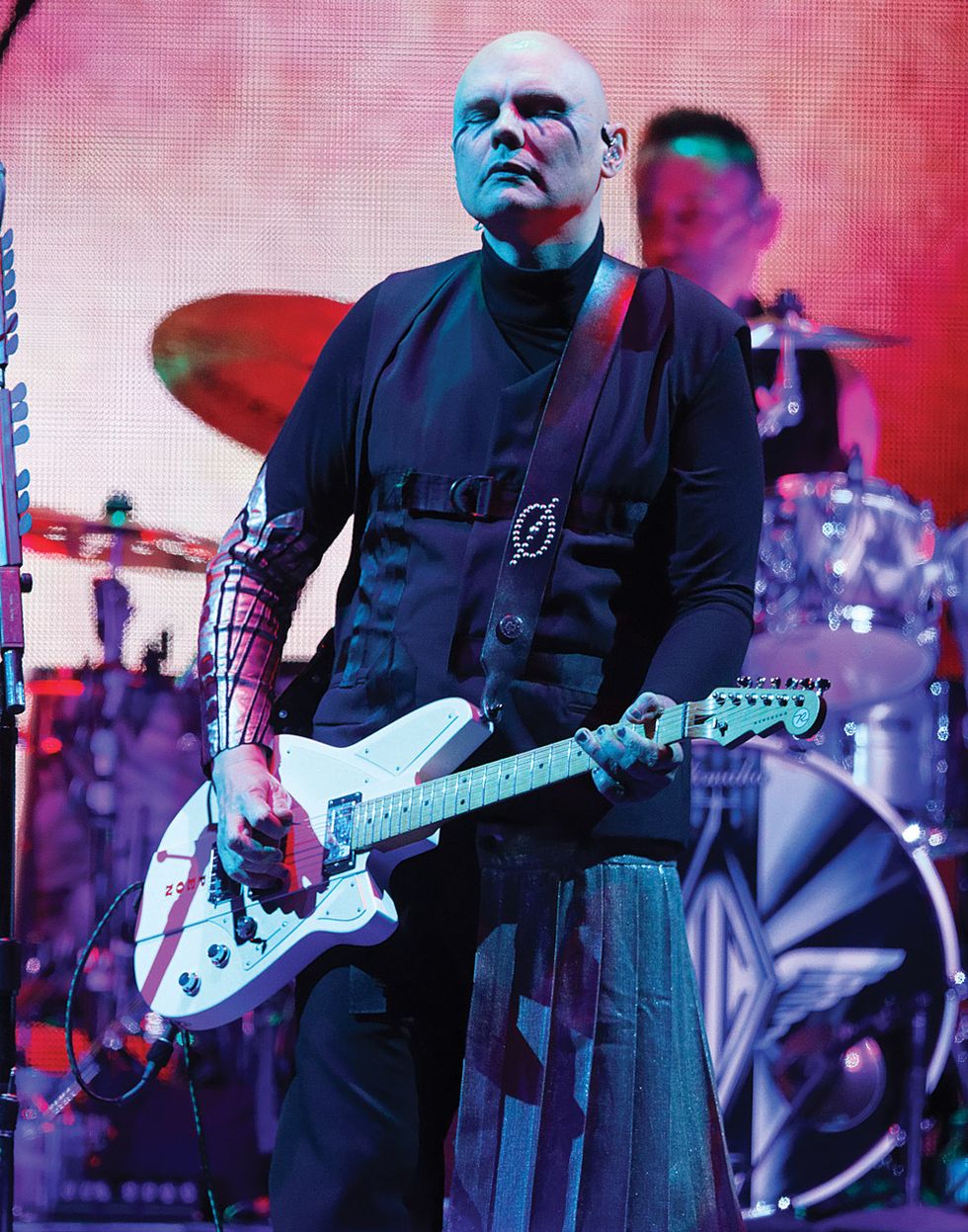

Besides that book, right now he’s also composing several intricate conceptual albums (a follow-up to Cyr is “about three-fourths done,” Corgan says), he owns the National Wrestling Alliance, and he just opened Madame ZuZu’s, a plant-based teashop and art studio in Chicago, with his wife, Chloe Mendel. (They also have two small children.) He recently collaborated with Carstens Amplification on a signature amp, called Grace, which he helped design. And he broke the news to PG that there’s another Reverend signature guitar in the works. The prototype is pictured on our cover and in this article (above).

The Smashing Pumpkins original lineup of Corgan, drummer Jimmy Chamberlin, guitarist James Iha, and bassist D’arcy Wretzky mirrors the hybrid nature and push and pull of the group’s most celebrated work, Mellon Collie. Highs and lows of internal struggle and interrelationships are silver-lined with romantic, epic frolics in the light, yet marred by sorrowful valleys and conflict. At the height of their success in the ’90s grunge era—starting for the band with the 1991 debut Gish, building with Siamese Dream’s breakthrough wall-of-guitar sound in 1993 (that inspired generations of guitarists to seek that one-of-a-kind fuzz tone), to Mellon Collie, the album that blasted them into the top echelons of rock ’n’ roll history—the Smashing Pumpkins became one of the biggest groups in the world. After disbanding in 2000, Corgan formed Zwan, pursued solo works, and ultimately continued making music under the Pumpkins umbrella with a rotating cast. Guitarist Jeff Schroeder came into the fold in 2007 and remains a permanent member of the group today.

In 2018, James Iha rejoined the Pumpkins’ on tour for some live shows in L.A. and Chicago, and, not long after, he officially rejoined the band. With three out of four original Pumpkins’ reunited, they teamed up with Rick Rubin to make an eight-song LP called Shiny Oh So Bright, Vol. 1 / LP: No Past. No Future. No Sun. Those sessions served as a prelude to now, which is ramping up to be one of the most productive periods for the Smashing Pumpkins in more than two decades. Cyr is the first time original members Corgan, Iha, and Chamberlin have created a conceptual album together since 2000’s Machina.

The Pumpkins are a different band today, with three bona fide guitarists in Corgan, Iha, and Schroeder. (Iha could not take part in this interview, due to a travel conflict.) Corgan calls Cyr—which he wrote and produced entirely by himself—a new way forward. He says the tradition has always been: “Stick our foot in something new and see what comes out.” This time, Corgan worked primarily in Pro Tools and played heavily with layering synths and remixing Chamberlin’s drums. To say that Cyr is more of an electronic record is not to say that the arrangements are any simpler. The album’s musical range is wide and unpredictable, incorporating elements of prog, and, well, most genres really, with heavy bass synths, lush layering, and, of course, a few extremely aggressive metal-guitar nods.

The band always had one foot in the past and one foot forward, but today Corgan seems to be standing in the now, with a goal to make music that reflects the rare time we’re all witnessing. Cyr’s release date was delayed multiple times because of the uncertainty of COVID-19, but Corgan was adamant that it be released in 2020. “It’s kind of a blurry,” Corgan says with a laugh. “My one mantra was, it’s all gotta come out this year. I’m not waiting. Please don’t make me go through Christmas, like I just gotta get this thing out of my life, like move on, next page, put the album out. It’s just music, no one will die. Everything’s fine.”

After all, he’s got other things to do, and next up is finishing the sequel to Mellon Collie, which means, we’ll find out what happens to the Zero character. Corgan had this to say about it.

“There’s some interesting messaging in the usage of those characters and how it’s played out over time,” he shares. “If I was being a bit glib about it, I would say that at the dawn of the internet age, circa ’95, whether I realized it or not, I started dealing with the dissociative effect of the coming culture. Unfortunately, over the last 25 years we’ve gotten more and more dissociative as individual people and as a culture and as groups, and we’re falling more into factions. We’re less unified by common ideas. So on one hand you have the rise of the super individual, the brand, the avatar, but you also have the falling away of old institutional thinking about how groups can be peacefully together. It’s very much the stuff of cyber-punk novels and dystopic sci-fi movies and stuff like that. So, in a weird way, this character launched me into a set of ideas that I may not have explored otherwise, including my grappling with my own self through the prism of fame or whatever. So it feels right to me to try to finish the story. If we started here, now we’re here. How does the story end? I talked to the band about it and everyone was interested in the idea so, we’re off.”

Pretty deep stuff, even after a year like 2020. And sonically?

“It’s pretty out there,” Corgan says. “It’s as heavy as anything we’ve ever done and it’s as out there as anything we’ve ever done [laughs].”

Until then, there’s a new experimental Smashing Pumpkins’ double album to digest. Read on as Corgan and Schroeder take us through the making of Cyr.

When talking about Cyr, you use the word “dystopic” a lot. That’s a fitting theme for these times.

Billy Corgan: That’s my new favorite word.

TIDBIT: The Smashing Pumpkins' 11th studio album, Cyr, was written and produced entirely by Billy Corgan. The companion animated series, In Ashes, features five songs from the 20-song double album.

How was the songwriting process different or the same with Cyr as compared with past Smashing Pumpkins albums like Mellon Collie?

Corgan: Well, I think the beginning is always the same—it’s like a riff, a motif, a chord change or something like that. The difference now is, over the past two years I’ve learned how to produce records in a more modern way, and so I had to let go of the way I’d always produced records before. I had made kinda modernish records but I ran them through the prism of the way I would normally do stuff. So TheFutureEmbrace, my first solo record, was electronic-ish but it was still made in the same way I would’ve made a Smashing Pumpkins record in terms of process. But now with everyone using technology I had to … it’s a very different process by which to work.

Jeff Schroeder: I think maybe sonically it is a bit of a departure. There’s a lot of synths, and even if there are guitars they kinda sound like synths sometimes so it’s hard to tell. So, in that way, it is a departure, but from my experience of working with the band as a recording entity, which basically goes back to the Teargarden project and Oceania, the studio process is relatively the same in that it’s a very slow, meticulous way of engagement. It’s not a very “off the cuff” band. It’s very thought-out; the aesthetic choices are very strategized. It’s just more the culmination of discussions that we had over time about where we saw new material going. The way that I understood what we were trying to do is that anything that felt like the older-style material—which maybe we did with the Rick Rubin album, if he wanted to indulge in some of that we were more than happy to. But on Cyr, we were very much like, even if that’s a good idea, if it feels like an older-style song let’s put it aside and look for things that feel fresh and new.

Billy, you write songs on piano and acoustic guitar. For Cyr, was that a pretty even toss, or did you favor writing on one more than the other?

Corgan: To me, it’s just always about a germ of an idea that I believe in. I always believe that a good idea can be jumped up and down on. It needs to be tested. In the old days, we would get in the rehearsal space and play a riff for an hour or something like that, and it was sort of testing your interest and curiosity and whether it was sort of inspired. Something emotional or romantic. So this is just different, but it’s also the same: a melody in the shower, a dream. I’m whore-ish when it comes to ideas [laughs]. I’ll take ’em as long as I like them.

How did the idea for this year’s In Ashes five-part animated series come about? How did you select the five out of Cyr’s 20 tracks for the series?

Corgan: Because of COVID, we were concerned we weren’t going to be able to make any videos in the traditional sense. So this idea was hatched about animation, that seemed more fun. We talked about maybe releasing five songs before the album. It felt right to me, because of the different nature of Cyr, if I gave people a chance to hear the music—that they familiarize themselves with it as opposed to having kind of a gut reaction of hearing all 20 [songs] at one time. I’ve had way too many experiences where people overreact to an album on first listen. Some of my most favorited albums now are ones that people had a completely negative reaction to the first time they heard it.

Billy Corgan plays his BC1 Reverend signature guitar in Detroit in 2018. Corgan's current main guitar is a prototype of an unannounced new Reverend signature guitar, as seen in the opening photo of this article. Photo by Ken Settle

It’s funny, because after you released a few songs, “The Colour of Love” and “Cyr,” then a few of the heavier songs came out. A publication called Louder came out and said …

Corgan: They issued an apology?

Yes! They were apologizing for an earlier article where they admitted being “a tad premature” with their remarks about the nature of Cyr: “We can only assume here that Billy Corgan hates guitars and is deliberately toying with our emotions.” I found that quite funny to read—that Billy Corgan hates guitars.

Corgan: It’s rare to get an apology from the media. I knew that was gonna happen. I talked about it internally. I said, “The minute someone hears a synthesizer they’re gonna overreact.” Which is why I liked the strategy of putting out the songs and giving people time to absorb them.

[Laughs.] For somebody who hates guitars, I’ve sure sold a lot of other companies’ guitars. Not only that, I mean, Electro-Harmonix basically dedicated their Big Muff reissue to the Pumpkins because we helped them sort of rebuild the brand. So, I think we’ve done okay on the guitar [laughs].

Schroeder: It’s strange because the Smashing Pumpkins’ biggest song is probably “1979,” which would be very much in line with an album like Cyr in that it combines electronic music with certain styles of guitar playing. If you really have absorbed the whole catalog, and even songs that were hits, songs like “Ava Adore” or “Eye,” it doesn’t seem to me that this music is that strange. But if you only think of the band as “Bullet With Butterfly Wings” or “Cherub Rock,” then I could see it’d be shocking. But for people who really know the breadth and width of the band—even in the time I’ve been in the band—we’ve always done folky acoustic stuff to full-on metal stuff to electronic music. It’s always been part of the recipe.

Many celebrated guitarists and bands, like John Frusciante and Nine Inch Nails, use synthesizers the same way they use guitars.

Corgan: How about Eddie Van Halen? He wrote one of the biggest songs of all time [“Jump”] on a synthesizer. I get it. I grew up in a generation that was very suspicious of synthesizers. Even Queen put on their album “no synthesizers,” ya know? We’re just in a different world. It’s music, you know. Are you telling me Bach wouldn’t have used a synthesizer if he had access to one? They used whatever they had in front of them. And so did we. With us it was fuzz pedals and guitars, and then eventually it just turned into other things. Everybody always makes it a bigger deal than we make it, so we end up having to talk about something that we don’t have any particular … we just make music, you know what I mean?

Shiny and Oh So Bright with Rick Rubin was the first time you’d worked in the studio with James Iha in 17 or 18 years. How did you get back in the groove?

Corgan: To Rick’s credit, he just kind of threw us in the deep end of the pool. We just showed up and started recording. There was no strategy meeting [laughs]. We just kind of went back to what we’d always done. We set up in a circle and tracked songs and did what we did, and we went really fast. We did eight songs, I think, in four weeks, which for us is like a land-speed record. Yeah, I go back and forth on that. I do like the songs. I just don’t feel that our fastest work is our most representative work. Our most representative work is the work where we take the time to find something new to say. So in many ways, Shiny was what you would expect in a good and maybe not a good way. This [Cyr] is more what our tradition is: stick our foot in something new and see what comes out.

Jeff, what was that experience like for you?

Schroeder: People always ask, “Was that weird?” Because, you know, the person you basically replaced is coming back. There’s never been any weirdness at all, and, in fact, over time it’s really been a bigger blessing to me because now Billy does his thing on guitar, James does his thing, and it actually allows me to just be myself in the fold. I don’t have to replicate anybody else as much and just do what I do. It’s actually been very liberating.

When you’re at home writing music, what guitar do you pick up?

Corgan: I have these two old Gibson acoustics, probably from the 1940s, that I really like. Those guitars from that era tend to have the V necks. They’re real plinky. I don’t know why, but for some reason I prefer writing songs on guitars that are smaller sounding, maybe more percussive. I noticed once when I was listening to John Lennon’s unreleased demos, if you listen to something like “Strawberry Fields,” you really hear the rhythm that he plays with and you realize that the magic of a lot of his songs is the rhythm between the way he sings and the rhythm between the way he plays. I took that really to heart. There’s something about trying to find the inner rhythm in a song on acoustic early that establishes a permanent narrative that you’re later able to record.

When it comes to the studio process for Cyr, most of the album was arranged and written by Billy. Jeff, how do you approach entering that conversation and adding your colors of guitar into the fold?

Schroeder: I was still living in Chicago at the time, so I was more in and out of the studio as things were getting shaped. I was there and able to participate in those discussions, and we even tried some early versions of songs with more rock guitar and ended up not using it. Basically, once it’s time to start adding guitar, usually it becomes virtual sessions and I’ll work at home for a while and demo ideas and then pile them on top of the recording, do a mixdown, and send that. Or when we get together, we listen to it and go, “oh that’s a good idea.” Then maybe that becomes part of the track. It’s more like finishing a painting and going it needs a little bit of this over here, it could use that over there, and going and looking for those things. It’s very difficult work, actually, because it’s not like, “hey, just go in and play whatever you want.” It takes a lot of time, a lot of thought, and a lot of effort. It was a very methodical record. Every inch of that record was discussed. Numerous times. [Laughs.]

Billy, I’ve always had an appreciation for your storytelling. For Cyr, did you come up with arrangements or lyrics first?

Corgan: What I try to do as I arrange the song is, I sketch out vocal melodies, but I don’t go too deep into them. I just kinda riff on them. And then I don’t really drill down on what I’m going to sing or how I’m going to sing it until I’m writing the lyrics. Many of the songs on Cyr, I wrote the lyrics either the night before I was singing the song or the morning of. So I just dive in real hard and try to, not wing it, but I try to put myself in a place where I have to make decisions.

Guitars

Reverend signature prototype

Reverend BC1 Billy Corgan signature

Yamaha Billy Corgan signature acoustic

Two vintage 1940s Gibson acoustics

Amps

Carstens Amplification Grace signature

Vintage Sound City amp

’70s Laney Supergroup

Orange 100-series head

Effects

Yamaha CS-80

Skreddy Echo

Two MXR Phase 90s

Chicago Iron Octavian

Boss PS-2 Pitch Shifter

Strymon El Capistan

The Bloody Finger (custom pedal)

Catalinbread Giygas

That’s impressive, because I’ve read the lyrics for this album, and you use words in ways that are not typical. For example, in the song “Adrennalynne,” you used the word “jake” almost as a verb.

Corgan: Yeah, “jaked.” That’s a word you don’t hear a lot [laughs].

Did you get some of these words from things you’re reading or from different cultures? There’s a lot going on there.

Corgan: Sure, great question. I do read a lot. I average probably 80 to 100 books a year, so I’d like to think I’m literate. But in addition to that, I find that I’m attracted to words that aren’t used very commonly because it’s sort of like finding an old book and blowing the dust off it. There’s something sort of curious about, well, why did this word mean something and then why did it not mean something? You know that weird thing on Google where you can see where a word is no longer used? You type in a word and it will literally show you how the use of the word has dropped over time. Like “cynosure,” or one of those type of words. You’ll see that slowly in 1950 it peaked and it’ll go down. It’s so weird how culture works with words. I think 50 years ago the general American used 2,500 words in their vocabulary and now it’s gone down to 1,500. So we’re seeing a great reduction in language, and I’m attracted to re-pushing the boundaries out again. I’m also a big adherent of the great author William Burroughs, who really believed that—and Bowie was also a huge devotee of this—depending on how you use words, and what sequence, they reveal a hidden energy. The main idea being, I could say five words to you in a certain sequence and you would think, “oh, whatever.” And I could say those same five words in a different sequence and you would be offended and never talk to me again. So, I really like playing with language that way. As a guide, I just try and see what makes me uncomfortable. If it makes me uncomfortable, it’s usually a good thing.

Like you were just saying about word combinations, I think in “Confessions of a Dopamine Addict” you start out with a very simple phrase: “Love is easy.” I love how that started with the concept in the video and what’s happening in the song.

Corgan: There’s even a word in there, “inamorata.” I kinda knew the word but I had to look it up … is this really a word? Did I invent this word out of my brain? Cuz that’s happened, too. And even sometimes I’ll listen and think, “Couldn’t I have chosen something a little less weird?”

But there’s something about the violence in that, and I use that word loosely. There’s something about the discomfort of hearing words you aren’t used to hearing and phraseology that’s a different onomatopoeia than what you’re used to hearing. If you’ve listened to pop music over the last 10 years, and maybe it’s the influence of AI, but it’s getting more and more reductionist. Less words, the same words, the same kinda vowels, the same four chords. I’m a bit Victorian in that I’m sort of reacting against all of that.

Synths, guitar, and bass interplay on Cyr and are often hard to tell apart, but there are so many interesting layers on this album. It’s hard to tell what is actually a guitar or synth.

Corgan: That’s on purpose. I think it’s fun to play around with guitars that sound like synths and synths that sound like guitars. It’s a combination of a lot of things. I have a famous keyboard, the Yamaha CS-80. It’s the one ELO [Electric Light Orchestra] used a lot. They’re super expensive and they’re hard to get. Whenever you get one they’re almost always broken. So I was using that.

Schroeder: Basically, on a lot of songs there’s a lot of ghosting of synth parts, where I would use the Helix and use two fuzz pedals DI, and it would create this very buzzy synth kinda thing but still have the energy of the guitar. That was the weird secret weapon and that Yamaha guitar had this specific frequency range that it would fit in. It was always like “wow there it is.” It was magical.

Billy, do you play bass on Cyr?

Corgan: Yeah, I’m traditionally the bass player in the band, so [laughs]. There’s a lot of bass-playing on the record. We find that even for songs that have, let’s call it, more of a synth-bass basis, that by putting a real bass in there it sort of animates it in a way that brings it to life. And it makes me think of the times that I’ve played with New Order and stuff like that. There’s something about that combination. There’s something beautiful about the cleanliness of a synth on its own, but adding a little bass makes it a little more rock ’n’ roll.

Jeff Schroeder plays a Les Paul on Smashing Pumpkins' older songs, but his current main guitars are four custom Yamaha Pacificas, built for him by the YASLA Custom Shop. Photo by Debi Del Grande

Billy, when you were tracking guitar parts for Cyr, were you using your Reverend signature?

Corgan: Yeah, in the past few years my main guitar for electric has been the Reverend signature model. It’s a really unique guitar. It’s got an incredible clarity to it. I’m playing a prototype that I’m working on with Reverend right now. I’m really excited about it.

Is it the same body shape?

Corgan: Slightly, but it’s a totally different guitar. I don’t want to give it away. We haven’t given it a name yet. If you announce something and there’s nothing there yet, people get mad, like, “I want it now. Why can’t I have it now?” I have to be a bit clandestine. The cool thing is Joe Naylor, the original owner of Reverend who still designs and has his own pickup line, does custom pickups for me, so these are new custom pickups that are different than the other ones.

What amps were you using?

Corgan: For the Cyr album we used a bunch of different stuff. I’ve done a signature amp with Carstens Amplification, which is called Grace, that’s just come out. He makes his own amps, so he’s not a big manufacturer. It’s a super-high-gain head. I used that. I used an old Sound City, and then two vintage Laney amps. One is what Tony Iommi used to play in the mid ’70s, so I have that actual amp. I also have a vintage Laney Supergroup Tony Iommi model.

I’ve been using Marshalls less and less, partially just because it’s become the sound of rock and I’ve always just gravitated in a different direction. I don’t wanna have everybody else’s guitar sound. Marshall’s great. It’s an incredible sound, but there’s something about playing with different gain structures that’ll change your playing a bit if you let it happen.

Schroeder: The amp that I primarily used was a mid-’70s, 50-watt Marshall that belonged to K.K. Downing from Judas Priest that Billy bought, and it sounds phenomenal. I used a ’66 Fender Bandmaster that I own on a few tracks for clean stuff. There’s actually a few parts that are the Line 6 Helix Native plug-in. Sometimes I demo them out, and I’ll use Helix because it sounds the same and gives you so much flexibility. A few times it was like, “wow that sounds perfect as is,” and we just end up re-amping or recutting it.

Jeff, what were your main guitars during the Cyr sessions?

Schroeder: Basically I used only two guitars: a ’72 Les Paul Deluxe with mini humbuckers and a Yamaha prototype guitar that I don’t think has an official name yet. It’s a bolt-on guitar with a roasted maple neck, stainless steel frets, alder body. It has three single-coils. They are the Seymour Duncan YJM Yngwie Malmsteen pickups. It was built by the Yamaha L.A. Custom Shop.

You mentioned another prototype that is in the cover photo for this issue.

Schroeder: Over the last year, the Yamaha custom shop built me four Pacificas. They’re pretty much like super-strat ’80s-style guitars with 24 frets, maple necks, one has a maple fretboard, and three of them have pau ferro fretboards, which I really like. They all have a Floyd Rose and Seymour Duncan Hunter pickups in the bridge. Three of them have a special Hunter in the neck. They don’t normally sell that, and then they have the SSL-5 in the middle. The bright fluorescent red guitar on the cover has a Sustainiac in the neck, and I use that a lot, too. I really love that. They’re just amazing precision machines. It’s the first time in my life that I’ve felt I can’t complain about anything on a guitar.

Do you ever go down the rabbit hole with pedals?

Corgan: I have, but I ultimately find that I’m less and less interested in pedals. It’s weird because now there’s so many great pedals and so many great boutique dealers who do all sorts of cool stuff. I have a massive vintage collection anyway, so it’s not like I’m really wanting for more pedals. Catalinbread recently sent me a pedal they’d made that I really like. It’s for distorting bass, so I could see using that on the next Pumpkins’ record. I’m gonna sound like my father but as I get older I’m more and more interested in the guitar-and-amp sound. If you can find the right guitar-amp thing, it just records in a particular way.

Do you feel that way about your new signature Carstens amp?

Corgan: Yeah. I’m tracking Pumpkins demos using the signature amp. I’ve also been using one of those Orange, I can’t remember what it’s called, but it’s like their high-gain Orange. I got it from the son of the guy who originally designed Orange. Love that amp, that sounds really great, too—a little cleaner, a little more stark in the mids, but that’s probably why metal guys like it. On the new Pumpkins stuff we’re working on, there’s definitely some big riff stuff, so I’m trying to find a new way to do the same wall of sound [laughs]. I’m at a point now where I just want pure power. I don’t want anything between me and the amp.

I love your guitar tone. I always have.

Corgan: The thing about those tones is we got used to playing at deafening volume. So when you’re playing all the time in that you get really attuned to what rattles the soul from a guitar sound. It’s cool to hear that stuff because it’s so aggressive.

“Wyttch” is one of the most metal songs on the album. It has such a cool hook, but also a killer chugging rhythm guitar part. Who is playing those guitar parts?

Corgan: I think everybody’s on the song. I’m playing the main stuff. I usually play the main stuff because it’s my riff, if that makes any sense. It’s like, if you write the riff it’s kinda your thing to figure out. The main guitar is just one guitar. It sounds like there’s more but there’s only one. We sort of got a good laugh out of that. Because we thought, everyone’s going to hear these synths and they’re going to bitch and moan, and then they’re going to hear this song and then what are they going to say?

How would you describe James Iha and Jeff Schroeder as guitarists? What type of players are they in the Smashing Pumpkins?

Corgan: Jeff is super skilled—he’s the most skilled out of the three of us. He can pretty much play anything. He’s been doing those shredding videos with Michael Batio and he lives in that world and I’m in awe of his ability. His nickname is “the shredder.” I think he even took lessons with Michael Batio not too long ago, and I know he remains friends with George Lynch. He brings that sort of level of knowledge to it. He can do all the sweeps—all that shit’s beyond me. I stopped practicing years ago. I look at that stuff and I just shake my head. I’m totally in awe of people who can play like that. I’m friends with somebody here in Chicago who’s son is maybe 11 and he goes to School of Rock. He posted this thing the other day of him playing “Eruption” perfect, note for note. Really good technique and he’s only 11 years old and I’m like, “fuck, I can’t play like that.”

Guitars

’72 Les Paul Deluxe with mini humbuckers

Four Yamaha LA Custom Shop Pacificas with Seymour Duncan "Hunter" pickups (bridge and neck), Seymour Duncan SSL-5 (middle), FU Tone upgrades on Floyd Rose Bridges

Yamaha RevStar RSP20CR Black with Seymour Duncan Whole Lotta Humbuckers

Yamaha Prototype Guitar with Seymour Duncan YJM Fury pickups

Amps

Randall RM4 Preamp with 4 Salvation Audio Modules: MatchVox, Voxy Face, Mash-All +, and JJ Dirt

’70s 50-watt Marshall (belonged to K.K. Downing from Judas Priest)

’66 Fender Bandmaster

Mesa/Boogie Simul-Class 2:Ninety

Orange PPC412AD 4x12 cabinet (Black) with Celestion G12H30 speakers

Effects

Line 6 Helix Rack with Foot Controller

Line 6 20th Anniversary Green Sparkle DL4

Dunlop JB95 Joe Bonamassa Cry Baby Wah

Eventide H9

Foppstar Royale Preamp Pedal

Electro-Harmonix Synth9

Spaceman Gemini IV Dual Fuzz Generator

Spaceman Mission Control

Fender Yngwie Malmsteen Overdrive

JHS PG-14 Distortion Pedal

Walrus Audio SLO Reverb

Cooper FX Arcades

Catalinbread Formula No. 55

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball Super Slinky (.09–.042) for E standard

Ernie Ball Regular Slinky (.010–.046) for Eb

Ernie Ball Earthwood Medium (.012–.052) for acoustic

Dunlop Tortex 1.14 mm (electric)

Dunlop Tortex .60 mm (acoustic)

James is very much like the world that we grew up in. We weren’t trained—both of us. And so the playing is very intuitive. You’re as likely to play one note as play a bunch. It’s not an intellectual thing. It’s more of an emotional relationship to the instrument. And because we learned from people like Johnny Marr and Robert Smith, our relationship with the guitar is probably different. I kind of straddle the two worlds, because I was a shredder type but I also learned and played the other type of guitar. So it’s a nice balance because really James is more on the intuitive emotional side and Jeff’s more on the shreddy side, and I sit in the middle. So there’s really nothing we can’t do as a trio. That’s the nice part about it.

Billy, you and drummer Jimmy Chamberlin have a special connection. Was that immediately there or was that something that’s developed over time?

Corgan: It took time to develop as musicians, and then our personal relationship took a whole lot longer because we’re just very different personalities. But musically by the band’s second or third year we really started to connect. We’d grown up on similar music, like Rush and Zeppelin, so we had a common language we could speak when we were talking about rock music. The crazy thing with Jimmy is there’s nothing he can’t do as a musician, but he’s also very emotional in terms of how he approaches it. He’s very lyric driven and melody driven. So as a songwriter there’s this incredible responsiveness where I can totally riff out and he can play any of that stuff no problem. And then when I play something like “Tonight, Tonight,” he knows how to come in behind the lyric and support it and lift the song up in a way that I think very few drummers could. So I’m blessed to have this literal armament of capability behind me with whatever we want to do.

And then on the Cyr record, he’s totally fine with taking a bit of a backseat and being more of just a beat maker. No ego, no complaining. He’s almost laughing about the lack of drum fills. Obviously, there’s nothing he can’t do, so let’s try this other thing that we normally wouldn’t do. He’s a really interesting person that way.

You’ve said the Melon Collie and the Infinite Sadness sequel “feels important.” Why does it feel like now is the time?

Corgan: I’d always planned to do a follow-up, but I didn’t think it was ever going to happen because of the status of the band. I think the solidity in the band, where we’re at in our lives, the fact that we can still play super-heavy rock really well. It’s like, well if you’re gonna do it, now’s the time. It feels right.

You’ve always been a big mental health advocate and very honest. Is writing multiple albums simultaneously helping you process what is going on in the world in 2020?

Corgan: Normally I would say no, but I think so. It’s weird, you know. We’re blessed as Americans in that we’ve been able to be inwardly indulgent. There are other cultures and places in the world that don’t have the same freedom and latitude that we have. For the first time in my lifetime, we’re sort of on the precipice if wondering, is that going to change? Are we entering a great unknown? Certainly America has had its issues, the Civil War being the most notable as far as almost tearing the country apart. For people to openly talk about civil war, insurrection, succession—this is pretty novel for us who’ve lived here in the last 50 years or so. You have to grapple with some bigger issues than whether or not indie rock has a future. There’s the politics of an indulgent culture. Like, did you see what so and so pop star said? That’s an indulgent culture self-effacing into its own navel.

Black Sabbath is one of your ultimate influences, but I’ve heard you reference Neil Young quite a bit lately. What is it about Neil’s music that’s resonating with you in these times?

Corgan: Neil is one of those true independent artists who’s charted his own path. It’s admirable and, in a weird way, the world has finally caught up to that’s the best way an artist should be. Neil’s funny though. He’s kinda all over the map and, depending on your mood, kinda like Bob Dylan, you can always find some version of Neil that suits the mood you’re in. He’s one of those touchstone artists that I come back to again and again. He’s like a fine wine; he’s just right all the time. There’s something beautiful about his celebration of his life experience that ultimately trumps whether or not the guitar is in tune or something you’d point to in a lesser artist. He seems to be able to transcend that.

If music had an odor, what would yours smell like?

Corgan: [Laughs.] A rotting rose.

Schroeder: Lavender. [Laughs.] Because if you think about it in terms, animus male/female, lavender is not entirely feminine and not masculine. It kinda embodies the two. With Smashing Pumpkins, intermixing those types of elements are very important and it’s the crux of the sound.

Do you think D’arcy will ever come back into the fold?

Corgan: No. Darcy, that’s a dead end. That’s what I always tell people: She made it very clear that the bridge is burned. One thing I’d like to point out, her and I spoke for two years before it turned into a public fiasco. So we had two years of conversations about making amens and trying to put some pieces back together. So no one was more disappointed than I that not only did it end poorly, it turned into some stupid clickbait thing. But she had every right to express herself that way. What I like to say is, the way we’ve chosen to express ourselves is to be in the band.

I know people like drama but the most important thing is the band. In the case of us three, we chose to make the band more important. It’s not like we don’t have issues. It’s not like we’re magically okay and somebody else isn’t. The issues are there; we’re a family, we go through them. The way the three of us have chosen to deal with that is to put it through the band and put it through the music. At the end of the day, I was made out to be this evil person but the decision was hers.

Have the things you need to say as a musician changed over the years, or do you still feel driven by the same forces that drove you when you started?

Corgan: I’ve definitely learned to come from a different place. In the beginning it was very much about I belong or I need a seat at the table. And then in the middle it was like I’m not sure I want to be here, but I’m willing to talk about those feelings. And then lately it’s about, okay I’ve made it this far, and if I’m gonna say something, I need to say something with some real heart and some force behind it.

It’s an interesting journey, because I’ve always been open about it. The lovely part is, if you’re honest with yourself you come to a place where you’re like, “Wow, I really do like doing this, I’m good with this.” We’re talking about 25-year-old songs and what pedal did you use on Siamese Dream. The fact that people care is pretty amazing. It’s humbling. It’s like, cool, this is what life’s about: celebration, and accomplishment. Don’t get too lost in any part of it—just keep dancing and keep moving.

Billy Corgan plays a Halloween 2020 acoustic set, stripping down select songs from Cyr, including “The Colour of Love” and “Cyr,” and mixing in Mellon Collie’s smashing hit, “1979,” and Pink Floyd’s “Wish You Were Here” for good measure.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)