When I was a kid, I wanted to be an archeologist—until the day I shared the dream with my mom.

“Why would you want to do that?” she cried. “You’d just spend your life in some dingy closet, polishing pottery scraps with a toothbrush!”

Fortunately, mom was more supportive of my guitar fantasies—in fact, she taught me to play. By the time I’d mastered the fiendish F chord, my archeology dreams had faded, along with my hopes of receiving a mini-bike as a bar mitzvah present. (I got a Jazzmaster instead.) Yet I’ve always maintained an armchair interest in ancient civilizations. My wife and I were even planning an archeology-oriented trip to Syria a couple of years ago, but, um, some stuff happened in that corner of the world, and the trip got nixed.

But living in the American West, we have archeological riches closer to home, particularly the remnants of the great Ancestral Puebloan civilizations (often referred to as the Anasazi, Navajo for “ancient ones”). About 1,000 years ago, these ancestors of the modern Pueblo people created the lofty cliff dwellings and grand cities whose ruins dot Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, and Colorado, including the vast complex at Chaco Canyon. I recently had a chance to revisit a favorite site, Wupatki, about an hour north of Flagstaff. And this time, I had music on my mind.

Sinagua Slapback Wupatki boasts glorious sandstone ruins, the largest of which were created by the Sinagua people during the 12th century (Photo 1). The site includes a large stone ring (Photo 2) widely believed to be a ball court like the ones associated with the Maya and other Mesoamerican cultures. (It’s the northernmost example of its kind.) A growing body of evidence hints at cultural exchange between the ancient Puebloans and Central America. (My take: “How could there not have been?”)

When I first visited Wupatki 25 years ago, I noticed a uniquely eerie echo when standing within the stone ring—a series of short but perceptible slaps as sound waves ricocheted between the low stone walls. Back then we lacked the technology to digitally capture the effect, but this time I packed a mobile interface with the aim of snaring an audio snapshot so I could clone the sound in the studio using an impulse response reverb. (I discuss this technology in my April 2014 Recording Guitarist column.) I squatted in the mud and clapped. The echo was every bit as spooky-cool as remembered. I unzipped my bag—and realized I’d left the interface at my hotel, two hours south in Sedona. (I wonder whether the Ancestral Puebloans had a word for “D’oh!”)

So I just set my iPhone on a rock in a puddle, fired up iOS’s free Voice Memos app, and started clapping, as heard in Audio Clip 1. The results as captured through the phone’s cheapo built-in mic aren’t promising. The echoes don’t sound terribly dramatic, and there’s wind noise, plus my scuffling feet and heavy breathing. Time would tell if I got anything good.

Photos 3 & 4 — The conical coal kilns in a remote corner of Death Valley generate an eerie, flange-like reverb.

Photos by Joe Gore.

D’oh! Redux History repeated itself a few days later as I returned home via Death Valley. I’d driven to a remote mountainous corner of the park to check out the Wildrose Coal Kilns (Photo 3). Designed by Swiss engineers and built by Chinese laborers, these spooky-beautiful conical structures were used in charcoal production during the 1870s.

It was “D’oh!” déjà vu: Again, I was unarmed—it didn’t even occur to me till I was standing inside one of the kilns (Photo 4) that these stones cones generate bizarre and capture-worthy reverb. I set down my phone and clapped, stomped, and clacked rocks, as heard in Clip 2. The echoes were shorter than at Wupatki, but they regenerated longer, producing an almost flange-like resonance.

Photo 5 — Impulse-response reverbs (such as Apple’s Space Designer, seen here) let you clone ambient spaces using clips of percussive sounds recorded in the target location.

Studio Surgery

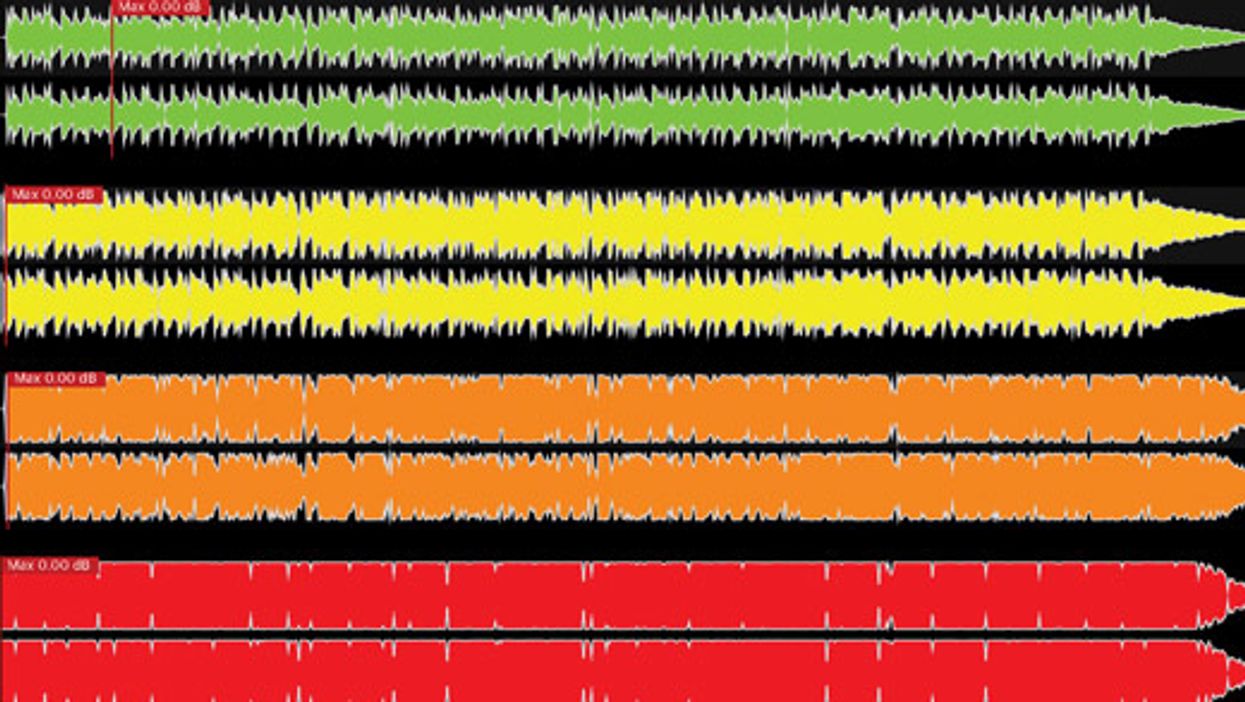

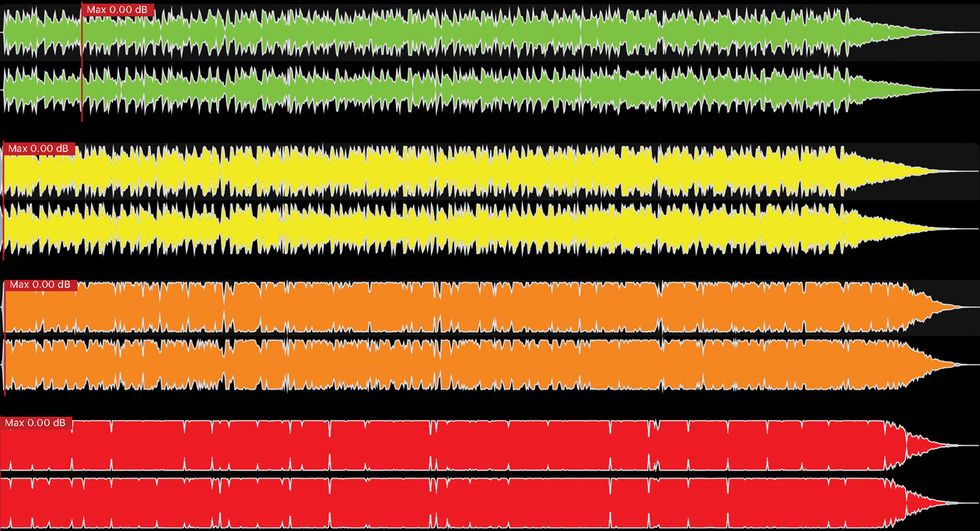

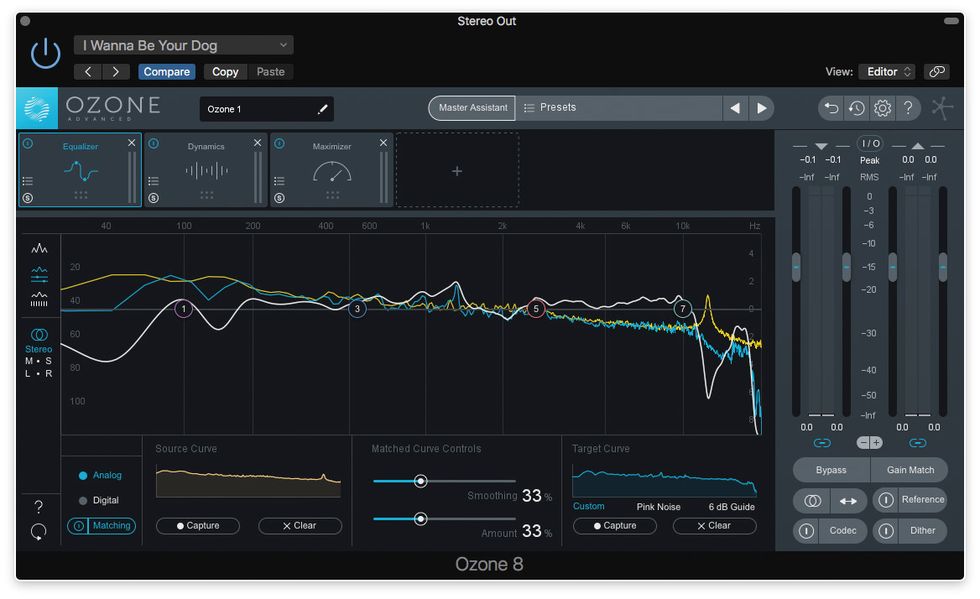

Back home in my San Francisco studio, I hacked away at these lo-fi recordings. I filtered out background noise using iZotope’s RX4 audio repair software, my first experience with the product. Holy crap, it worked great! Compare Clip 2 to Clip 3, the same with RX4 processing. Next I snipped the file, isolating some of the better-sounding hits. (The isolated clips run from the initial percussive attack through the last audible echo.)

Next, I just dropped these short recordings into Space Designer, the impulse-response reverb plug-in included with Apple’s Logic Pro, saving the results as presets (Photo 5). (The procedure is similar for all IR reverb plug-ins, including Audio Ease’s Altiverb, Waves’ IR-1, Avid’s TLSpace, and shareware products like LiquidSonics’ Reverberate and SIR1 from SIR Audio Tools.)

The results, while better than anticipated, weren’t dramatic enough, so I ran the short clips through a slow-attack compressor, maintaining the initial impact while fattening the tails of each sound. Hear the result in Clip 4, where I play a classical guitar (low-tuned and strung with absurdly expensive Thomastik-Infeld “rope core” strings) through the Wupatki ball court reverb. Clip 5 is the same performance, played through the coal kiln reverb. (The mixes are excessively wet, but I wanted to emphasize the effect.)

These lo-fi files don’t yield the most accurate of spatial snapshots, yet these reverbs definitely evoke their idiosyncratic sources, providing cool, unique sounds you’d never get from a factory reverb preset. But would they work on an entire mix?

Death Valley Drums

At some point I realized that the claps, clicks, and clunks from Clip 2 might have another use. I dropped a dozen or so isolated sounds into Battery 4, Native Instruments’ sampling drum machine plug-in. I fiddled with tunings and EQ till the sound of large rocks on dirt felt like kick drums and clicks behaved like shakers or hi-hats, retaining some reverb tails to convey the cone’s eccentric color. I sequenced a simple beat, and then overdubbed nylon- and 12-string guitars, a Dobro played acoustically with an EBow, and some primitive synth bass, moistening the instruments with my new Space Designer coal kiln preset (Clip 6).

I won’t claim the results sound “good” in any audiophile sense, nor are they an entirely accurate portrait of the modeled space. Still, the ambience feels eerie and evocative. Many engineers and musicians rightly fear the homogenizing effect of digital audio and its ubiquitous plug-ins. But sometimes the best way to break free from “in the box” production is to capture fresh colors and make your own crayons.

Until you get around to creating your own otherworldly ambiences, help yourself to mine! This free download includes my edited impulse response recordings in WAV and AIFF formats, ready to insert into any impulse-response plug-in. I’ve also included some of the processed “drum” sounds culled from my field recordings. Just drop them into a sampler and pound away!