When it comes to comping, we guitarists can learn a lot from B-3 and electric piano players. I’ve always been inspired by how ace keyboardists use inversions and subtle substitutions to create harmonic and rhythmic motion inside the tune’s basic changes. You hear this wheels-within-wheels approach in old-school R&B, blues, and soul-jazz.

For example, imagine a band is vamping on a dominant 7 chord for two measures, marking time until the next chord change. To spur harmonic momentum, a B-3 player might play a series of secondary chords that color the primary dominant 7 chord. Though the essential harmony is static during this two-bar section, we hear chordal movement. What’s going on?

Walk the Line

These secondary voicings are often constructed

around a melodic line that’s

related to the chord of the moment. One

classic line that shows up time and again

in groovin’ music from New Orleans funk

to Memphis soul derives from boogie-woogie

piano and incorporates two chord

tones—the 5 and b7—of whatever dominant

7 chord the band is playing at that time,

plus the 6, which acts as a stepping stone

between the 5 and b7 chord tones. Typically,

the line ascends and descends in a 5–6–b7–6 pattern and is harmonized with several

other notes. As we’ll see in a moment, this

harmony may be located above or below

the 5–6–b7–6 line.

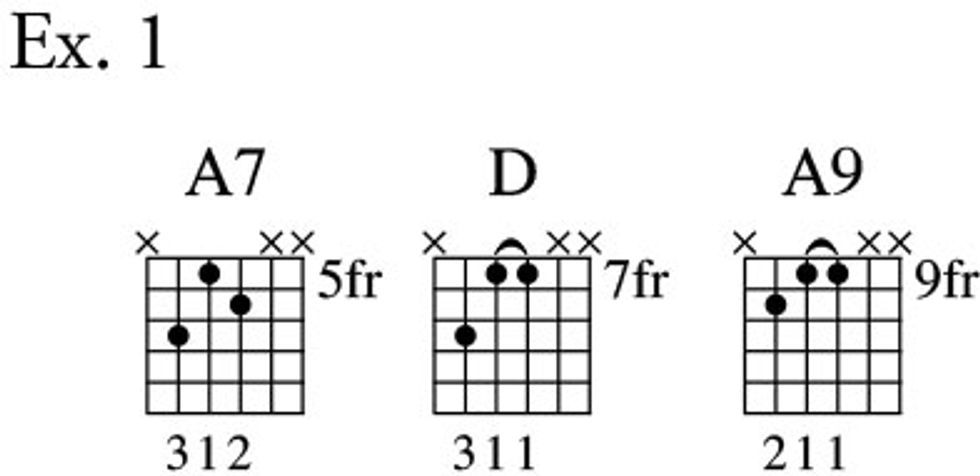

Ex. 1 shows three chord voicings we’ll use to start exploring line-based comping. As you fret these grips, notice how they each occur on the 5th, 4th, and 3rd strings. By staying on these strings, we keep the chords in the guitar’s middle register, an area that grants singers or soloists melodic elbow room.

In Ex. 2, we put these voicings to work to create an A7 comping pattern, which typically occurs over an A pedal tone established by the bassist. Cycle through this phrase several times at a moderate tempo, listening to the harmonic movement and feeling the syncopation in the middle of each measure.

Click here for Ex. 2

There are several things to consider about this passage. For starters, the 5–6–b7–6 line—which, in this case, is E–F#–G–F#—ascends and descends on the 5th string. Another is that both the A7 and A9 grips are rootless. As long as the root—A—is implied by the bassist or another instrument, you won’t miss it. If you’re flying solo, with no one to pump out a pedal tone below you, you can keep these changes focused within the overarching A7 tonality by simply plucking a low A from time to time.

Unlike its companions, the D chord has a root (it’s located on the 3rd string). But in this context—sandwiched between A7 and A9—the D chord isn’t functioning as a full-on change. Rather, it simply provides momentary tension and release within the comping pattern. This quick, superimposed IV chord is a staple of gospel and blues piano.

One more thing: If you’re into music theory, you’ll notice that our A9 chord is also a first-inversion Em triad, as well as a partial G6. When comping, it’s often the case that you can name a particular cluster of notes several ways, depending on the context. Because we’re comping against an A7, we hear these three notes as a partial A9 chord. In another setting, we might identify them differently.

You can transpose this A7–D–A9–D comping pattern up and down the fretboard. For instance, shift the whole operation up to D7 in the 10th position, and you get a D7–G–D9–G phrase. Start two frets higher in the 12th position and you’ll have an E7–A–E9–A move that sounds great against E7. With a little imagination, you can create a soulful I–IV–V comping pattern to fill out an entire 12-bar blues progression in the key of A. Try it.

Flip It

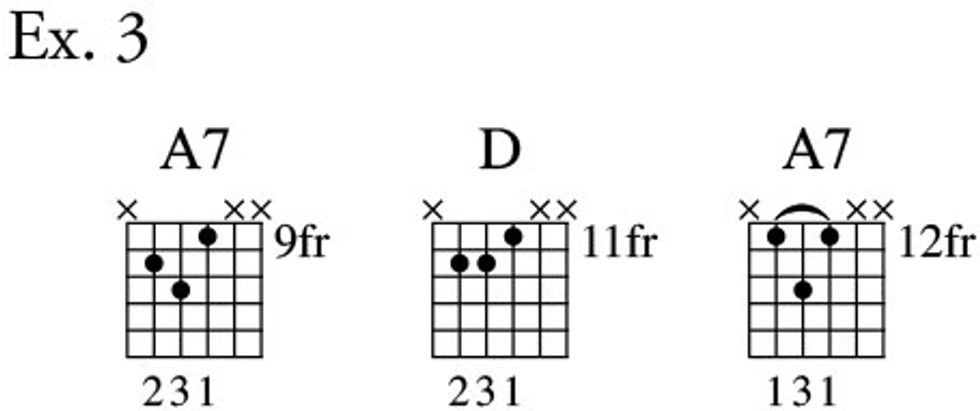

Next, let’s rework the 5–6–b7–6 line so it

becomes the top voice in an A7 comping

pattern. Ex. 3 gives you the grips, and Ex.

4 illustrates one of the many ways you can

move through them. This particular phrase

comes straight out of ’60s organ-driven jazz

by the likes of Jimmy Smith, Brother Jack

McDuff, Shirley Scott, Lonnie Smith, Jimmy

McGriff, and Groove Holmes. As you wrangle

this phrase, notice how our E–F#–G–F#

line now ascends and descends on the 3rd

string. If you have a Leslie simulator or a

Uni-Vibe pedal, by all means kick it on.

Click here for Ex. 4

Mix and Match

So far, we’ve placed the 5–6–b7–6 line in

either the lowest voice or highest voice

of our comping patterns. But you can

mix the two approaches, as shown in Ex. 5. Here, the 5–6 (E–F#) portion ascends

on the 3rd string, while the b7–6 section

(G–F#) descends on the 5th string. It’s a

cool sound.

Click here for Ex. 5

All Together Now

These comping patterns really come

alive when you weave them into a longer

progression. In Ex. 6—which sounds especially

sweet played with a relaxed swing

feel—we apply our new moves to a V–IV–I

sequence in the key of A. By playing a

voicing on virtually every beat, you generate

momentum and harmonic complexity

without obscuring the underlying cadence:

E7 (measure one), D7 (measure two), and A7 (measures three and

four). Try dropping this sequence into the last

four bars of a 12-bar blues or shuffle in the

key of A.

Click here for Ex. 6

Next month, we’ll explore more ways to build comping patterns around lines. In the meantime, work out these moves in other keys and then look for ways to use them in your next jam or recording session.

Ah-ha!

Comping. The word “comp” is jazzbo slang for “accompany,” as in, “I’ll comp while you take a solo.” Comping also implies playing a chord progression with some rhythmic variation.

Scale and chord formulas. You’ll often see a scale, chord, or phrase expressed numerically, such as the 5–6–b7–6 line discussed in this lesson. These numerical formulas are derived from a major scale—our musical yardstick—and come in handy when you want to describe an item’s musical construction, independent of any key. Every chord type or scale type has a formula, and once you know it, you can apply it to any major scale to generate the notes for the given chord, phrase, or scale in that key.

For example, the formula for a minor 7 chord is 1–b3–5–b7. To identify the notes in, say, Cm7, simply apply its formula to the parallel major scale—i.e., the major scale that shares the same root. In this case, that’s a C major scale (C–D–E–F–G–A–B), so applying the minor 7 formula yields C–Eb–Bb–G, Cm7’s chord tones.

Pedal tones. A pedal tone (or pedal point) is a note that sustains against a passage, acting as a tonal anchor. A pedal tone is usually played in the bass register below the musical activity, but can also ride above it, as in a blues turnaround when the highest note remains static while other intervals ascend or descend against it.