I'll always remember the guys in the office cracking up when I answered the phone—them overhearing a conversation devolve into regular utterances of “oh hey," “oh wow," and “thank you," and then arrive at “Well, we would be honored to make something for Mr. Cornell" as if he was going to arrive wearing a top hat and monocle for a fitting. His tech Stephen Ferrara-Grand reached out to us and raved about the Cannonball pedals we'd made for Vintage King that Chris had used in the studio, and said that Chris wanted two more pedals with that same kind of raw, industrial look to be delivered that week, before Soundgarden went on tour.

I was uncomfortable delivering something we'd been making exclusively for a retailer. Keeping a promise of exclusivity is something I take seriously, even when it inconveniences our business or gets in the way of making a customer happy. That said, they were out of stock and not due for a restock in time for the tour. I instead promised we'd make something he would like just as much, if not more. I immediately drilled out two enclosures, then left to buy some Hammered gray spray paint from the nearest Ace Hardware. I went back home, rigged up a metal coat hanger to a planter hook, and sprayed the enclosures on my front porch. After taking the time to let them dry enough to be handled, I baked them in a repurposed toaster oven I'd bought from Goodwill for $3 with “No Food!" sharpied boldly onto the door. Fun fact, DIY kids: Once you use a toaster oven to bake enclosures, you will not want to put English muffins in there.

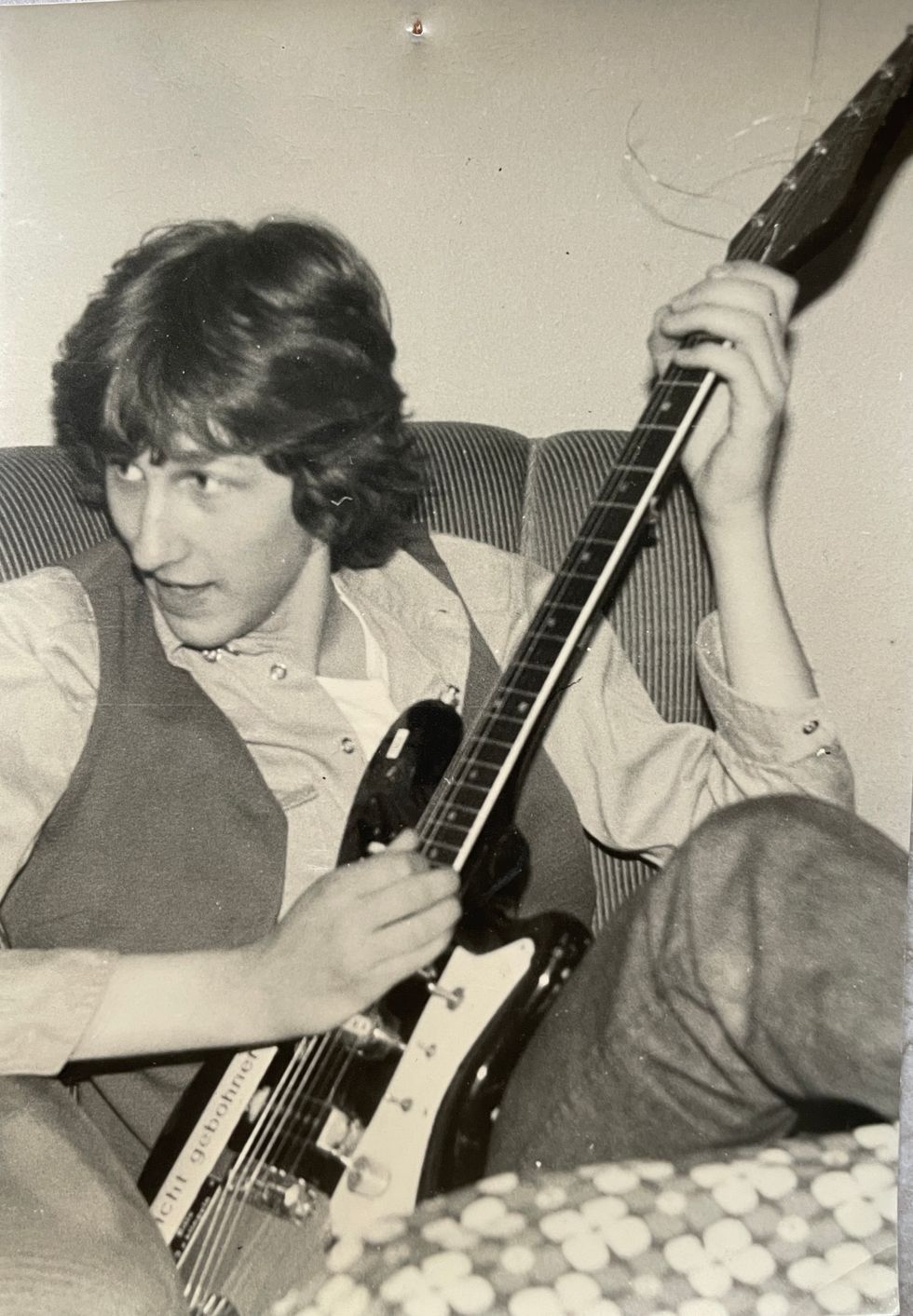

The next day, we wired the pedals with a voltage sag circuit we'd been experimenting with, tested them repeatedly, and labeled them with an old hand-held Dymo labeler that used to be in my mother's ceramic tile workshop. I remember how we were so fearless and haphazard and excited to get this done that I had no backup plan to propose if he didn't like them. I sent Stephen this very pic, and held my breath for the go-ahead. By the end of the day, we'd been paid, given a shipping address for FedEx, and away they went.

Chris Cornell's passing deeply affected me. It wasn't just that this was a musician I deeply admired, though that definitely mattered. I remember buying Badmotorfinger in December of 1991 along with Pearl Jam's Ten and putting them both into my boom box on repeat. Ten was easier to fall in love with faster. Three of the first six tracks became massive hit singles. It was produced and mixed in a fashion I didn't find dissimilar from the Badlands or Cult albums I'd devoured in high school. As an introduction to the Pacific Northwest music that would be labeled “grunge," Ten was a perfect gateway drug for hard-rock kids who'd grown up in the 1980s.

But for me, Badmotorfinger was a snakier, more insidious, and deeper love. The rhythm section's relentless churning, detuned guitars, and odd meters found ways to wind themselves past my initial, reflexive discomfort into deep memory. And above it all—wailing, circling, brooding, gathering steam, and then exploding like a dragon—was that voice. As grunge hit its cultural apex and then fell toward a derivative decline, my college roommate years later would say it was easier for labels to find bands that tried to sound like Pearl Jam than Soundgarden, because impersonating Chris Cornell was downright impossible. And to have seen Cornell play guitar, acoustically and electrically, was to realize we were witnessing someone who deeply loved the craft of music—who wasn't content to simply coast on his talent and re-enact his legend.

When Cornell turned the corner past age 50, I thought we'd have him for a long time. I thought we'd get to see him really grow older and age, and have to conserve his energy and pace himself. He'd record and tour less frequently, and then when he toured, we'd buy our tickets with some nervous anticipation and wonder if he still had it. We'd get into our seats or find ourselves a space in general admission, the show would start, and we'd be waiting. The band might start with something like “Slaves and Bulldozers," steadily building in volume, then dropping once the singing started, and right as we'd begin to doubt him, like an aging wizard he would cut loose on that “now I know why you've been shaking" before the first chorus. And just like that, we'd know he still had it.

Since his death, I've seen photos people have sent me from the last Soundgarden shows where one of these pedals was visible, still on his board. May we appreciate all he shared with us during his time here. We were honored to play a tiny part in it.