The first scene in Davis Guggenheim’s acclaimed 2008 documentary, It Might Get Loud, shows Jack White stringing a wire across a crusty plank of wood outfitted with a Coke-bottle bridge, a Tele bridge pickup, and nails for a tuner and a tailpiece. It’s possibly the most primal lap-slide ever, but despite its roughness it sounds positively badass through White’s ancient valve amp. What’s more, though the film is chock full of luxurious closeups of the iconic and priceless instruments and amps used by White and guitar gods Jimmy Page and the Edge, this opening scene cuts to the chase in a way we rarely consider: For all the emphasis, time, and money we guitarists put into tonewoods, pickups, amps, tubes, effects, speakers, and even cables, we often spend very little time thinking about the core component without which a guitar simply becomes a collection of wood—strings.

The history of stringed instruments stretches back centuries. For most of that time, strings were created using organic materials, primarily animal hair and intestines. Historians frequently refer to “cat gut” strings, but that’s misleading, because generally the intestines of farm animals such as sheep, lamb, or cattle provided the components for early strings. But that all changed early in the 20th century, when guitar builders began using steel strings to increase durability and volume. Gibson was an early proponent, and C.F. Martin & Co. also transitioned to steel strings in the 1920s.

Guitar-string manufacturers of the era typically evolved from firms producing materials for violins and other instruments. As just one example, the D’Addario family focused on violins before branching out into guitar strings in the 1930s.

As the guitar became more prevalent in the post-war era, the need for accessories grew considerably. In 1962, Ernie Ball capitalized on this need and expanded from just selling instruments in his guitar store to producing strings and accessories.

“Ernie Ball is the pioneer of [the sorts of ] electric guitar strings that you know currently in the shops,” says Derek Brooks, who works in the company’s artist relations department. “All the popular gauges that you see are from Ernie Ball and his forethought into combining string gauges.”

Around the same time, GHS was launched in 1964 in Battle Creek, Michigan. Their Boomer series of strings marked the beginning of major growth for the company. And in 1970, Martin acquired the Darco String Company (which was founded by members of the D’Addario family) and began manufacturing its own strings. Other companies have joined the fray over the decades and, today, an expansive industry produces a wide variety of guitar strings.

One of the more recent developments in string manufacturing and marketing is a focus on maintaining the freshness of the strings, much like beer producers that use tinted bottles, born-on dates, and other strategies to provide a higher-quality product. GHS Strings offers a resealable zipper multipack for storing strings prior to use in order to preserve quality. And Dean Markley’s Blue Steel strings—a game-changing product for the company—were inspired by a scientific magazine article.

“The concept came from an article in Popular Mechanics decades ago about how drill-bit, tool, and die manufacturers were cryogenically freezing their products to maintain their sharp edges, thus increasing the lifespan,” says public relations representative Josh Vittek. “A sidebar to that article mentioned a violinist doing the same to her strings to extend the life and performance. From there, the idea was born.”

Behind the Bullet

Most steel strings are constructed with a brass ball end attached to the string using winds of its core wire. In the early ’70s, unhappy with how ball-end strings would shift inside a Stratocaster trem block—and thus cause tuning problems when players worked their wang bars—engineers at Fender developed the Super Bullet string. These have a cylindrical piece of brass clamped directly onto the string (left). As shown in the trem cross-section, the “bullet” sits snuggly in the string channel, reducing movement and improving transfer of string vibration to the bridge.

Frozen strings are just one of the myriad considerations that manufacturers use to improve and differentiate their products. Indeed, the massive variety of options can be daunting, especially to beginners. With all the different gauges, materials, marketing tactics, packaging considerations, and swag offers, the “string wall” at your local retailer—that mecca of spooled wire and prophylactic-like packaging behind the counter—can be intimidating and overwhelming enough as to be more akin to a wailing wall.

“It’s like the toothpaste aisle,” says John Biggs, a tech journalist and hobbyist guitar player. “Intellectually, I know there’re different ingredients and formulas in the tubes. One’s for whitening, one’s for cavity control … but on an emotional level, I stand there and wonder if there is really any difference at all.”

No doubt similar reasoning guides many guitarists to just stick with whatever brand of strings accompanied their guitar, whatever their favorite player uses, or whatever happens to be on sale. For many, that initial strumming in the guitar store establishes a sort of template in the musician’s mind for what the instrument should sound like.

Tim McNair, general manager of Martin’s string division, relates the story of a collector who purchased a new Martin and then contacted the factory about getting additional strings. “I sent him our Clapton’s Choice strings,” says McNair. “He calls me up a couple of days later after he got the strings and he says, ‘You broke my guitar. This is not the guitar I bought.’ I explained that, no, those are not the strings that came on the guitar in the dealership. So I sent him [a set of ] the 4100s we had on that guitar at the time, and he calls and says, ‘You fixed it.’ I don’t think people realize that the set of strings affects how the guitar sounds.”

Construction Types

To understand strings, there are a few somewhat

technical areas to get a handle on,

including how strings are made. What we

consider to be a simple guitar string is actually

the fusion of two main components.

First, there is the core wire—basically the inner foundation of the product. Some string companies use a hexagonal (six-sided) core, others use a round core.

“You have to marry the tensile strength against the flexibility of the core wire,” says Martin’s McNair. “If you get it too stiff, it’s not going to play well—the vibrations start to slow down, and you don’t get as much pressure against the fret.”

Second, there is the wrap material that encircles the core. The shape of this wrap material often drives the designation of how a string is “wound.”

Roundwound strings are constructed by wrapping a round metal wire around the core (imagine a spaghetti noodle twined around a chopstick). They are the most common string type today, and they’re considered a good, all-purpose option for multiple genres of music.

Flatwound strings are constructed by wrapping a flat, ribbon-like material around the core (imagine a linguine noodle around the chopstick). They produce warm, somewhat subdued-sounding tones often preferred by jazz players.

Halfwound strings combine the qualities of roundwounds and flatwounds. In fact, some manufacturers take a roundwound string and grind off the edges. This produces a string that offers reduced finger squeak.

Although these three types represent the overwhelming majority of strings on the market, some companies are exploring new winding methods. For example, Dean Markley’s Helix HD line uses a wrapping material that has an elliptical shape. Further, Rotosound’s Jason How adds that machinery and construction speed are also important factors. “Rotosound is one of a few string manufacturers that designs and builds all its own machinery entirely in-house. This means we can control and adapt to every possible function of the string—tension-control management, wrap-wire angles, wrap speed etc. … Many string companies wind their strings at ridiculously high spindle speeds to achieve efficiencies. We have a unique system that allows us to run the machines at the perfect slower speed to produce a superior product and still achieve maximum output.”

Metal Types

What your strings’ individual components

are made from affects the final sound at least

as much as the type of construction. Most

manufacturers use steel cores but employ

numerous combinations of metals and alloys

to produce a wide range of tones across

their product lines. It’s a bit like the contestants

in a chili cook off, where some prefer

cayenne, some use red pepper, and others

choose paprika to augment their cherished

recipes. Guitar string producers do the same

thing, just with more volume.

Steel is used for a bright, crunchy tone.

Nickel, once the industry standard, is used for a slightly warmer, “vintage” tone.

Down to the Wire

Gauges, Tension, and the Core-to-Wrap Ratio

Guitarists are typically used to thinking about string tension—that

is, how easy or difficult a set of strings is to play—in terms of

gauge. For instance, tuned to high E, a plain .011 string has more tension

than a .009 made of the same material—a fact our fingers can easily

confirm. However, when it comes to wound strings, there’s more to

the question of tension and feel than meets the eye. It’s true that, tuned

to low E, a .048 string feels tighter than a .046. But can there be a difference

in tension between .046 strings made by different companies,

assuming they’re on identical guitars and tuned to the same pitch?

The answer is yes, and although the differences may be subtle, it’s an area worth exploring. As you can see when you clip a wound string and peer at its cross section, it comprises two elements: the core wire and wrap wire. To achieve a given string gauge, manufacturers may vary the ratio between these two wires. One brand may have a thicker core and thinner wrap, while another may use a slightly thinner core but make up the difference in diameter by using a bigger wrap.

These differences affect feel, explains Eric Cocco, vice-president of LaBella Strings. “The tension of a musical string can be adjusted by simply combining different core and wrap wires. This can also be varied by using different tensile strength for the core and wrap wires. As an example, an electric guitar gauge of .042 can be made by using a .016 core and a .013 wrap wire. Another way of building that string could be with a .019 core and a .0115 wrap. The gauge would be the same— .042—but the string with the .019 core would be much stiffer.”

The core-to-wrap ratio also impacts tone. “You want a significant mass on the winding,” says Jason Everly, president of Cleartone Strings, “because that’s what makes the sound waves. The thicker the mass of the wrap, relative to the size of the string, the more audible low-end frequencies you’re going to get. You’re trying to get close to a 1-to-1 ratio between core and wrap wires—at least on an acoustic string—but that’s difficult because the wrap wire will shear the core wire when you reach that ratio. So that’s the game, and everyone has their own top-secret formula as to how they overcome this and how they adjust for it.”

If you’re interested in fine-tuning your guitar’s playability and tone, it pays to experiment. Companies put a lot of thought into how they manufacture wound strings, and the core-to-wrap ratio is an important factor in their designs. —Andy EllisBronze refers to a mixture of metals, frequently a combination of copper, zinc, brass, or other materials. It’s generally used as a wrap for acoustic-guitar strings to provide bright, crisp tones with good volume and projection.

Phosphor-bronze combines phosphor with bronze to increase the durability. It’s also generally used for acoustic guitar strings to provide a combination of brightness and warmth.

Gauges

Perhaps the most common terms you’ll hear

guitarists use when talking about strings

are their gauge—that is, how thick each

one is. You might hear a fan of shredding

metal solos saying, “I play eights” or “I play

nines,” which is simplified guitar speak for

saying they prefer using a set of strings that

has a .008" or .009" high-E (or 1st) string.

Lighter gauges (.008 or .009 sets for electric, or .010 or .011 set for acoustic) are easier to play and most appropriate for newer guitar players. The most common gauge sets for electric guitarists in general are .010 sets, but some blues and jazz players often play .011, .012, or .013 sets because they tend to yield a more taut and burly tone. Fans of detuned metal or baritone guitar also play heavier sets out of necessity—thinner gauges are too slack and lose their pitch too easily when tuned to lower registers.

As for acoustic guitar, .012s are the most common sets for two reasons: First, most acoustic players don’t play electriclike leads on their flattops, so they don’t need them to be as easy to shred on. Second, more of your tone is generated directly by the physics of the guitar body with an acoustic, and heavier strings yield a richer, more robust acoustic tone.

As we mentioned above, keep in mind that these single-number designations (e.g., “I play .011s”) are just ballpark figures, because virtually every string manufacturer makes at least a couple of varieties of sets in each general gauge range. For example, both Dunlop’s Medium sets and its Light/Heavy sets have .010, .013, and .017 gauges for the top three strings, but the Mediums have .026, .036, and .046 gauges for the lower three strings, while the Light/Heavies have .030, .042, and .052 gauges for a little extra oomph on the E, A, and D strings.

In the past, players were constrained by manufacturer offerings in terms of gauges, but today, there is an almost limitless palette. “Throughout most of the 20th century, standardized electric and acoustic guitar gauges were sufficient,” says Brian Vance, director of product management at D’Addario. “However, today there are so many popular styles and trends that it is often necessary for players to go outside of standard gauge sets to get the effect they desire. Whether it’s for open tunings, drop tunings, baritone guitars, 5-string guitars, 7-string guitars, or a variety of other reasons, many players are opting to go their own way and customize their string selection.”

Coatings

Many guitar string brands offer sets that are

treated with a variety of proprietary coatings

and polymers to reduce corrosion, fret wear,

and the audible squeaking sounds players

sometimes experience as they slide their

fingers from one neck position to another.

Some players dislike coated strings (although

they seem to be more widely used in the

acoustic realm) claiming they muffle the

string’s natural tone or sometimes have a

bit of a sticky feel. However, some manufacturers

claim there isn’t an appreciable

difference, while others say a different feel

was precisely the goal for developing coated

strings in the first place.

“It’s about giving players options,” says Steve R. Rosenberg, project manager at Elixir Strings, the company that pioneered coated strings. “Originally, it was about the feel of the string—the idea that it gave you a different feel. [But] after tens of thousands of strings, [we realized] this long-tone-life benefit trumped the original concept.”

Today, depending on target markets and branding strategies, some companies choose to highlight the difference of a coated string while others downplay the difference between the playability of coated versus uncoated.

D’Addario’s Vance says, “Our EXP coated [acoustic] strings look, sound, and feel like traditional strings, while providing a barrier against corrosion and wear. They retain their new-string tone and last three to four times longer than traditional strings.”

Actual coating methodologies vary from manufacturer to manufacturer. Elixir Strings, for example, owns a patent on materials and technologies that coat the strings’ cracks and crevices.

“As you play, dirt and gunk accumulates between the windings, in the gaps,” says Elixir’s Rosenberg. “What that does is add mass, but more importantly, it’s restricting the motion so your string can’t freely vibrate. That’s what’s causing those highs to roll off and lose that bright tone people are looking for. Unless you are protecting the gap between the winding—physically preventing material from accumulating—you’re not significantly changing tone life.”

Colored strings, such as the Neon series from DR Strings or the guitar and bass sets from Strings by Aurora, illustrate another reason to balance coating size with playability and longevity. While enabling players to customize instrument appearance, colored strings also reveal the worn spots. “If you have a coating you’re saying is really thin, but you can’t tell it’s there, if you put pigment in it, you’d see how fast it went away,” says Thomas Klukosky, factory manager at DR. “If you’re going super thin—down to micron coatings—you’ll rub off the plating. As soon as your string hits the fret, it starts wearing away whatever the string is made of.”

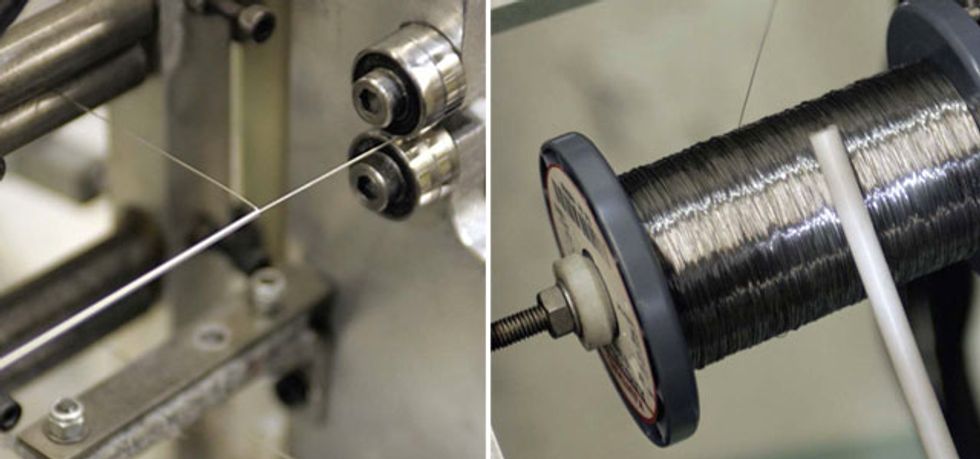

Machinery and construction practices factor into quality of string production, says Jason How

of Rotosound, which controls all of its hardware in-house, from machine design to operation

speed. Photos courtesy of Rotosound

Smart Tools to Aid Your Search

Big-name guitarists (and their techs) get

courted by reps from every imaginable string

company, so they have it a bit easier when

it comes to selecting their go-to strings. But

how should a weekend warrior go about it?

“Patiently,” says Dean Markley’s Vittek. “Developing as a musician is a long process. Finding the tools you need to do so can be even longer. Try them all. Trial and error will be the only way you come to a conclusion of what string works best for you.”

Russ McFee, president of GHS Strings, agrees with the trial-and-error nature of the process. “The best advice is to experiment. Strings feel different to every player, and you have to find the one that fits your own playing. In our opinion, a new player should keep the gauge of the string on the lighter side—for both electric and acoustic. As the player gets more experience, then he or she can try heavier gauges for a little more punch and volume or for different tunings.”

Many guitar companies help beginners via interactive website tools that help you zero-in on a particular type of string. For example, GHS features a graphic of a string delineated with various string models along a continuum from bright to mellow. D’Addario’s website has a similar string-selection tool that also enables you to add filters for coating, wrap material, and construction. Ernie Ball offers three different web tools: The Tone Universe and String Player offer different ways to listen to clean or distorted recordings (single-string or chord) of various string types, while the String Finder lets you reference the company’s diverse roster of famous endorsees to help you decide which string type and gauge might work for you.

The Future of Strings

The string industry has invested millions

of dollars in research and development to

bring us some pretty cool innovations over

the years—innovations that are easy to

take for granted or overlook. A medieval

traveling minstrel accustomed to stretching

gut strings across his lute would be

shocked at the variety and combinations

of alloys, gauges, and coatings available in

the 21st century. And if one thing’s for sure

after talking to reps from so many of these

companies, it’s that we can count on them

continuing to blaze new trails.

“There is room for improvement in the areas of corrosion-resistant materials and processes, new alloys with varying tone and texture characteristics, and more variations based on the feel and tension of the strings,” says D’Addario’s Brian Vance.

Some industry experts even predict that younger players will come to expect features that traditionalists dismiss today. Further, society’s increasing awareness of environmental citizenship may also influence the future of guitar strings.

“I think a lot of companies are becoming more environmentally aware than ever,” says Russ McFee from GHS. “We continually look at ways to improve the process and cut down on material waste while maintaining a high-quality guitar string. The packaging that companies use will continue to evolve and be redesigned as we move forward, offering some exciting opportunities.”

In that initial It Might Get Loud scene, Jack White nails down a thick, heavy-duty wire that seems better suited to industrial lighting applications than music. In future generations, the same scene might be filmed with a gossamer thin fluorescent strand that seems as fragile as a spider web but is strong as steel. But whatever the future technologies, the string will remain as integral as ever—after all, there’s a reason one of our favorite nicknames for the instrument is “the 6-string.”