Okay, you’re restringing your acoustic guitar and discover that a bridge pin is stuck. Now what? It could be time for new bridge pins or this could signal problems with the bridge plate. Eventually, bridge pins wear out and sometimes break, so it’s important to inspect them every time you change your strings. It’s also smart to check the bridge plate too, because when the bridge plate begins to wear out, the consequences can be catastrophic for your guitar.

Understanding pins and plates. Most steel-string guitars use bridge pins to hold the strings against your guitar’s bridge and bridge plate. Bridge pins come in various sizes and can be made from plastic, wood, ivory, bone, and even brass. Each material offers a different tone and various degrees of longevity.

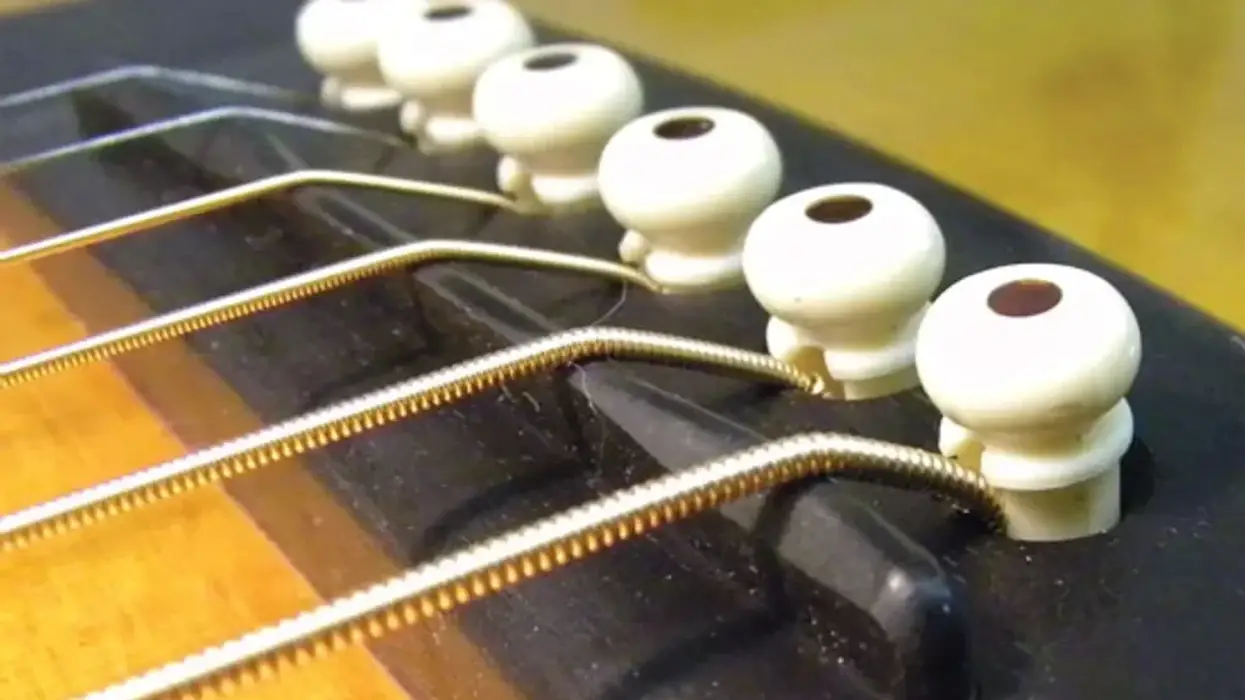

Fig. 1. Bridge pins hook the strings’ ball ends to the bridge plate, which is located under the bridge. In this interior view, the soundhole lies north, just above the X-brace.

A common misconception is that bridge pins secure the strings to the bridge. Actually, the pins hold each string’s ball end against the bridge plate located inside the guitar. The string then curves around, passes through the bridge, and runs over the bridge saddle. If a string’s ball end isn’t firmly anchored to the bridge plate, the string will slip and cause the pin to launch out of the bridge. Fig. 1 shows properly anchored ball ends.

Fig. 2. Bridge pins made from (left to right) ivory, plastic, ebony, rosewood, and brass.

Here are some pros and cons of common bridge pin materials (Fig. 2).

- Plastic: Inexpensive and readily available at any music store. Wears out easily and won’t enhance a guitar’s tone.

- Wood: Available at most music stores and improves sustain and tone. Can be expensive and often requires reaming out the bridge to fit properly.

- Ivory: Increases sustain, produces a warm tone, and looks gorgeous. Very expensive, difficult to obtain legally, raises ethical issues, and often requires reaming out the bridge to fit properly.

- Bone: Increases sustain, produces a brighter tone, and looks great. Expensive, difficult to find, and often requires reaming out the bridge to fit properly.

- Brass: Lasts forever, produces a very bright tone (good for guitars with excessive bass), and looks great. Expensive, difficult to find, and often requires reaming out the bridge to fit properly. Can be too bright for most guitars.

My personal preference is rosewood, ebony, or bone. Brass and plastic are my least favorite because plastic breaks easily and brass is too bright for my taste.

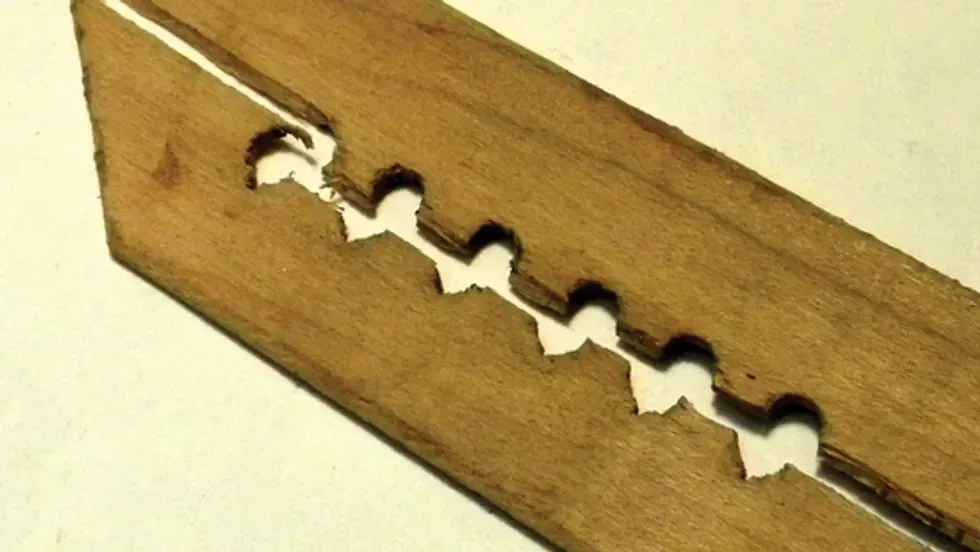

Fig. 3. A cracked bridge plate.

Fig. 4. A cracked bridge.

Wear and tear. When a bridge pin wears out or breaks, the string’s ball end travels up into the bridge. Not only can this cause the bridge pins to launch out of the bridge, it can cause the bridge plate and top to crack. When the bridge plate cracks (Fig. 3), the bridge can also crack (Fig. 4) and pull away from the top. To make things worse, the braces may then fail, further damaging your instrument.

If a pin is stuck inside the bridge, you can sometimes remove it by pushing the string down into the bridge and then pulling the pin out. If that doesn’t work, the pins may have to be forced out by pushing them up from inside of the guitar.

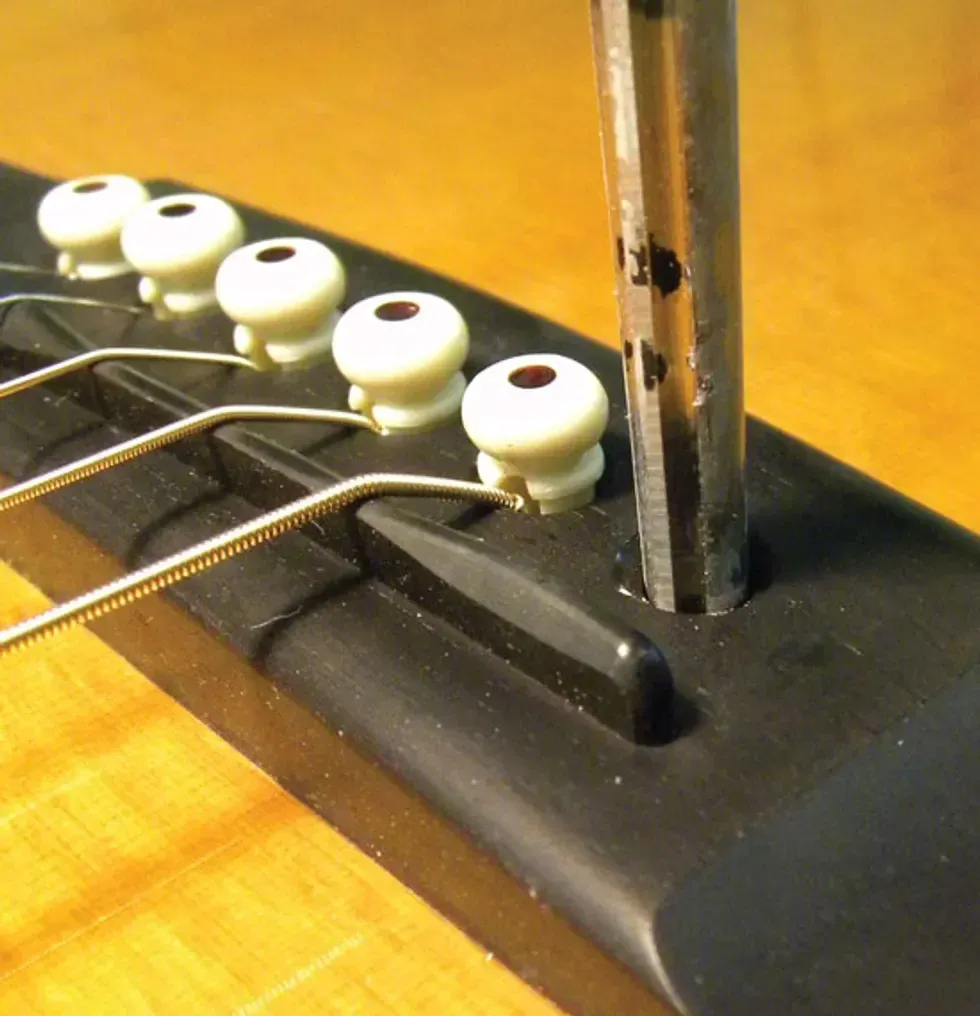

Replacing worn pins. If you see wear on the pins, that’s a good sign you should replace them. Fitting the pins correctly takes the proper tool and a lot of skill. To open the holes in the bridge to the proper size, I use a tapered reamer. These are available from luthier supply companies like Stewart-MacDonald and Luthiers Mercantile International.

Fig. 5. Improperly fitted pins stick up from the bridge.

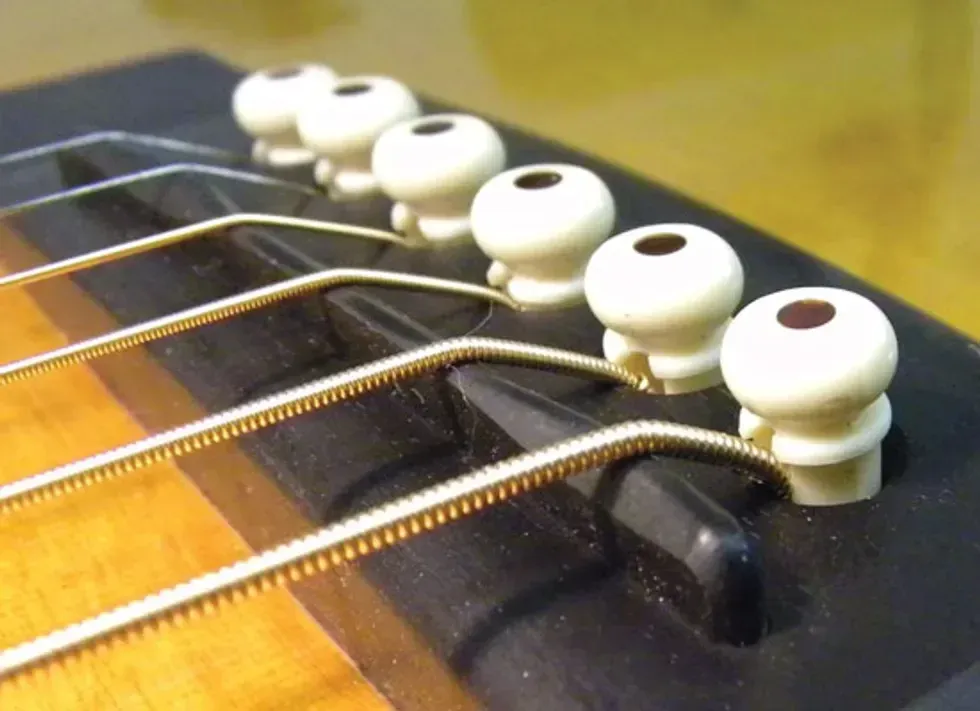

Fig. 6/7 Properly fitted bridge pins sit snugly in their holes with only the rounded top exposed.

The key to successfully fitting the pins is patience. If you don’t remove enough material from the hole, the pins will stick up and poke out of the bridge (Fig. 5). And forcing the pins into holes that are too small can crack the bridge. But if the holes are too big, the pins will fit loosely and can easily fall out. When fitting the pins, take your time and check the fit after each turn of the reamer (Fig. 6). The ideal fit is when you can press the pins into the bridge—with the string in place—down to the end of the flute, so that just the round top of the pins is exposed (Fig. 7). The fit should be snug, yet allow you to work the pin loose when you change strings.

Fig. 8. Some vintage guitars use non-fluted bridge pins.

Where’s my flute? Not all bridge pins have a flute or channel that runs down the center of the pin. The string travels down this flute allowing the ball end to hook onto the bridge plate. Many vintage guitars were made with a bridge and plate that had the flutes carved into them. For this type of guitar, the pins are solid or non-fluted (Fig. 8), and the same principles apply when fitting them. However, depending on what gauge strings you use, the flutes in the bridge and plate may need to be enlarged. It’s best to let a professional tackle that particular job.

Understanding the bridge plate. Using quality bridge pins will improve your tone, and properly fitted bridge pins will help prevent severe damage to your guitar. But remember, pins are only part of the story: Don’t overlook the bridge plate! Alas, many people do, yet it plays a crucial role in the guitar’s structural integrity.

Bridge plates are made from several types of wood and come in many different shapes and sizes. The most common material is maple, though many guitars have a plate made from rosewood, pear wood, or spruce. The plate provides stability for the bridge and, as we’ve seen, holds the strings inside the guitar.

Over time, a bridge plate can simply wear out. The holes in the plate gradually enlarge, causing the strings to travel up into the bridge. To repair worn holes, a skilled tech uses a specialized tool to remove a tapered disk of the worn-out wood, then glues in a new wood disk, and finally redrills the bridge pinholes.

But repair is not an option if the bridge plate cracks. If that happens, the entire plate has to be replaced—a much more expensive proposition. The bottom line? Inspect your pins and bridge plate regularly to stay ahead of unnecessary future repairs. To inspect the bridge plate, you’ll need a small mirror that will fit inside the guitar. You can buy these from the luthier supply companies I mentioned earlier, or you can repurpose small hand-held mirrors like those sold in auto parts stores. If you’re not confident you can spot problems, take your guitar to a qualified guitar tech or luthier for an opinion.