The guitar kingpin discusses the band’s new album, playing Ritchie’s licks, and his prodigious picking technique. He also offers two tips for every guitarist.

Deep Purple, one of the pioneers of heavy metal, is most famous for their hits like “Highway Star,” “Perfect Strangers,” and, of course, the guitar shop staple, “Smoke on the Water.” For 6-string fanatics, though, the band is all about the virtuosos that have occupied the guitar chair.

In 1968, Ritchie Blackmore helped form Deep Purple and brought with him a classical influence that proved rock guitar could seamlessly go beyond the confines of the minor pentatonic scale. Blackmore felt the blues was too limited. He was lauded as a guitar god since day one, and his style helped pave the way for Swedish sensation Yngwie Malmsteen’s neoclassical movement, which transformed the guitar sounds of the late ’80s. Blackmore was also a notoriously difficult personality, and while he had legions of fretboard fans, Blackmore and vocalist Ian Gillan were constantly at each other’s throats. In June 1975, Blackmore left Deep Purple to form Rainbow (originally Ritchie Blackmore’s Rainbow) with metal icon Ronnie James Dio. Tommy Bolin took over guitar duties with Deep Purple until the band broke up in July 1976. Several months later, Bolin died of a drug overdose.

In 1984, Deep Purple reunited with Blackmore back onboard. The group released Perfect Strangers, which achieved commercial success and ushered in a period of great prosperity. Blackmore got Gillan ousted in 1989 and replaced him with vocalist Joe Lynn Turner, who was in Rainbow from 1980 to 1984. Turner’s tenure with Deep Purple was short-lived—he recorded one album, Slaves and Masters, with the band—and Gillan was brought back in 1992. Things remained incredibly hostile between Gillan and Blackmore, and it all came to a head at a concert in November 1993, when Blackmore went missing on the intro to “Highway Star” only to reappear in the middle for a solo with an off-kilter performance. He then threw water at a cameraman. Four shows later, Blackmore quit the band and was temporarily replaced by guitar virtuoso Joe Satriani, who helped Deep Purple finish the tour.

Steve Morse, the acclaimed picker from the Dixie Dregs and a one-time commercial airline pilot, joined Deep Purple as a permanent member in 1994. Like Satriani, Morse also had a very distinguished career as a solo artist by then—including a mastery of technique that spans rock, jazz, classical, and country music, and a nearly singular command of blazing alternate picking. So, at first, he was apprehensive about the gig. He signed on with the intention of giving it a four-show trial period in the space of a week. When he met and rehearsed with Deep Purple in the venue’s dressing room, the night before the first show at a coliseum, the chemistry was apparent.

The late organist Jon Lord’s spontaneous harmonizing of Morse’s improvised melodies knocked Morse out, and he was sold. Soon after, Morse recorded on the band’s 1996 Purpendicular, and now, more than 20 years later, he’s clocked in more hours as a member of the band than Blackmore. Along the way, Morse has maintained his successful solo career and stints with various projects including Flying Colors—an all-star band featuring drummer Mike Portnoy and bassist Dave LaRue, among others—as well as a project with his guitar-playing son, Kevin.

On April 8, 2016, almost half-a-century after their formation in Hertford, England, Deep Purple was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Blackmore refused to attend because the band was not willing to perform with him. Surprisingly, current members Morse and keyboardist Don Airey were not inducted, although they both performed at the ceremony.

InFinite, Deep Purple’s 20th studio album, was recently released and features the classic Purple sound infused with Morse’s magic touch. The album was produced by Bob Ezrin, who Morse worked with during his years with Kansas. If you assumed that, in the age of Kanye and Justin Bieber, classic rock is dead, you’re wrong.

TIDBIT: Deep Purple’s new InFinite was produced by Bob Ezrin, whose resume includes classic albums by Lou Reed and Pink Floyd.

InFinite has already topped the band’s previous album, Now What?! and hit No. 1 in Germany and Switzerland, while cracking the Top 10 in 10 other European countries. The single “All I Got Is You” also hit No. 1 on Billboard’s Classic Rock radio chart.

Premier Guitar caught up with Morse on the road, shortly after the band commenced its “The Long Goodbye Tour.” Is this the final chapter in Deep Purple’s career, as implied by that name? That remains to be seen. In the meantime, they’re rocking as hard as ever—with Morse in that legendary guitar chair.

You’ve been in Deep Purple longer than Ritchie Blackmore. Do you take more liberties now with classic Deep Purple material?

Actually, no, I don’t think I do go too far out. In fact, I would say it’s gone the other way. Over the years, as we accumulate our own material, with this version of the band I play the stuff more straightforward. Even though I knew what I was getting into, I didn’t understand the amount of angst it causes people. Some fans just hate me because I’m not Ritchie—you know, the old diehards whose formative years were spent with Fireball or Made in Japan or something like that. The younger people have never seen any version of the band but this one, so they’re fine.

Given your virtuosic abilities and the complexity of your own music outside of the band, is it hard for you to hold back and play a song as technically “simplistic” as “Smoke on the Water?”

As a guitarist, your main job, maybe 90 percent of the time, is playing rhythm and getting the right pickup, right tone, and right dynamics when other people are singing or playing. So, playing the rhythm part with the best possible tone at each show—and, by the way, during each show the subs might be going crazy beneath the stage or in front of the stage, and somebody’s monitor might be louder so you gotta watch where you stand or you might be getting feedback if you’re right in front of there—you have to weigh all these things. Little things like picking the perfect spot or just how much volume will get the best tone on this show on this day. It’s always a challenge. I’m usually picking the notes with my fingers, and how hard you pluck—the more you pluck it, the more you get a thonk-y sound.

You pluck the notes for the intro, but I watched a video of you playing “Smoke,” and in the verse and chorus you switch to picking.

Yeah, for more definition.

Though you mention the importance of rhythm, in your career, as one of the premier instrumentalists of our time, you haven’t necessarily always had to fill that role. For instance, you’ve had contrapuntal guitar parts in your own music or with the stuff you wrote for the Dixie Dregs.

Yeah, that’s a good point. My guitar parts in the Dregs often were lines. Fair enough.

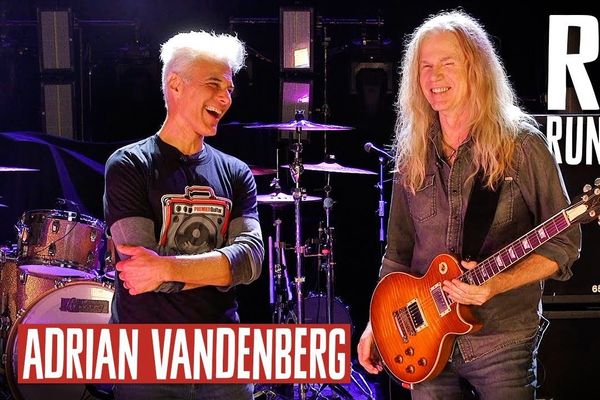

Here, Morse plays live with longtime bassist Dave LaRue in 2013. LaRue plays with Morse in three bands: the Steve Morse Band, Dixie Dregs, and Flying Colors. Photo by Paul Jendrasiak/Atlas Icons

What was it like working with Bob Ezrin again? I know you worked with him when you were in Kansas, on 1988’s In the Spirit of Things.

Actually, he’s the same to me. Always clever, always seeing and hearing all, and always full of good, useable ideas. It may not be what you want to hear, but he seems to be usually right. I mean, there’s more than one thing that will work with music. But his ideas always do work.

Are you attached to the ideas you bring in?

Writing is almost like improv. To me, my best place in the band is to provide lots of options and let the band figure out which one feels like Purple. Every once in awhile I’ll just say, “You’ve got to be kidding. This totally works. You guys can’t see this? Let’s try it, come on.” Sometimes I’ll try the hard sell. But usually I don’t get attached to it. I just keep bringing in other options. And I never have to worry about tailoring it to Bob, because he has no problems telling me what he thinks [laughs].

How do you strike the perfect balance with everything else you have at your disposal—the chops, the country thing, and the classical thing—and get it to fit Deep Purple’s music?

I pretend like Bob’s on my shoulder. I can just hear him saying, “No, no, no, no. Stick with the song; come on. Give me something with some weight.” [Laughs.] For me, there’s a density level of notes. There are only so many notes per phrase that will work and not give me the furrowed eyebrows from the guys or whatever. I’m just trying to find what’s best with every song.

I’ve played in a lot of cover bands throughout my life, and it’s a great experience because they’d have two or three overdubbed parts on the songs we played and you’d have to pick which one is the most important. Or you get a song where there are horn parts on it, and you have to play some of the horn parts, and you’re a guitar player. You just have to adapt in every song and try to fit, like I said, the density of it. Whether it’s dissonance or the solo sound or whatever. Try to make it fit the song the best.

The tricky thing is, your ears are really harmonically advanced, but you’re playing in a classic hard-rock band. So, you might hear something that sounds normal to you, but for many would sound too out there.

Don is very advanced, harmonically. He almost always plays along with the guitar riffs. But sometimes he’ll just have it in his head, you know, “I’m a British rock player. This is the way rock is supposed to be. This needs to be simple here. Morse is trying to add too much to it.” Bob will just say, “No, no, Morse. That sounds like a solo album. Come on.”

What is that intervallic phrase in “Time for Bedlam?” from around 2:27-2:40”

[Sings phrase.] It goes up in fourths. That’s something Don does a lot, and I join in with that. It’s two stacked fourths and you keep moving the inversion up higher and higher. When you play something like that, you’re striking three strings, and they can be in the middle of the guitar so you have to carefully mute the other strings.

Steve Morse’s Gear

GuitarsErnie Ball/MusicMan Steve Morse signature

Ernie Ball/MusicMan Steve Morse Y2D signature

Amps

Engl Steve Morse Signature E656 head

6 Engl 4x12 cabinets with Celestion Vintage 30s

Engl Z-9 MIDI footswitcher

Effects

TC Electronic Hall of Fame Reverb with Steve Morse TonePrint

3 TC Electronic Flashback Delay and Loopers with Steve Morse TonePrint

Ernie Ball VP Jr.

TC Electronic G-Major 2

TC Electronic PolyTune 2

Keeley Compressor

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball Super Slinky (.009–.042; .010–.046)

Ernie Ball medium picks

Ernie Ball straps

DiMarzio straps and cables

Custom 30’ cables made by guitar tech Tommy Alderson

Along those lines, or on something like your own classic, “Tumeni Notes,” when you arpeggiate chord shapes that employ a barre, how do you keep the notes separate? Do you roll the finger making the barre?

Yes. Rolling the finger on the one you want to hear, and lifting it slightly to mute the adjacent string.

When we spoke five years ago about Flying Colors (see “Flying Colors: Shredding Stereotypes” in the May 2012 issue), you said you’d be 20 to 30 percent faster if you employed techniques other than strict alternate picking. Have you gone in that direction or is alternate picking where it’s at for you?

I’ve got one spot in “Perfect Strangers” where there’s extremely fast sextuplets that are outlining the chord changes for a few chords. It’s similar to something Joe Satriani did when he was in the band, and he was doing the legato style. I just happened upon it while I was experimenting with many different techniques. If I picked the first note, hammered the second, and picked the third note of each string, that worked well. You get a lot of attack, but the attacks must be done very gently with the pick in order to make the phrases sound even. And you end up picking it like a dotted eighth/sixteenth or, more technically, swung eighths, to make it even sextuplets. I do that in one spot because when I ramp up and have my stiff wrist and arm picking every note, it sounds too violent.

It sounds tricky to time the pick strokes around the hammered middle notes.

It’s definitely a notch faster than I can play, but I still practice alternate picking the sextuplets every day.

Usually when people mix in legato on three-notes-per-string shapes, they do pick, pick, and hammer, it seems.

I don’t know, because I’ve just never really studied that or really paid attention to it. Normally, I just say, “I’m going to pick every note so I don’t have to think about it.”

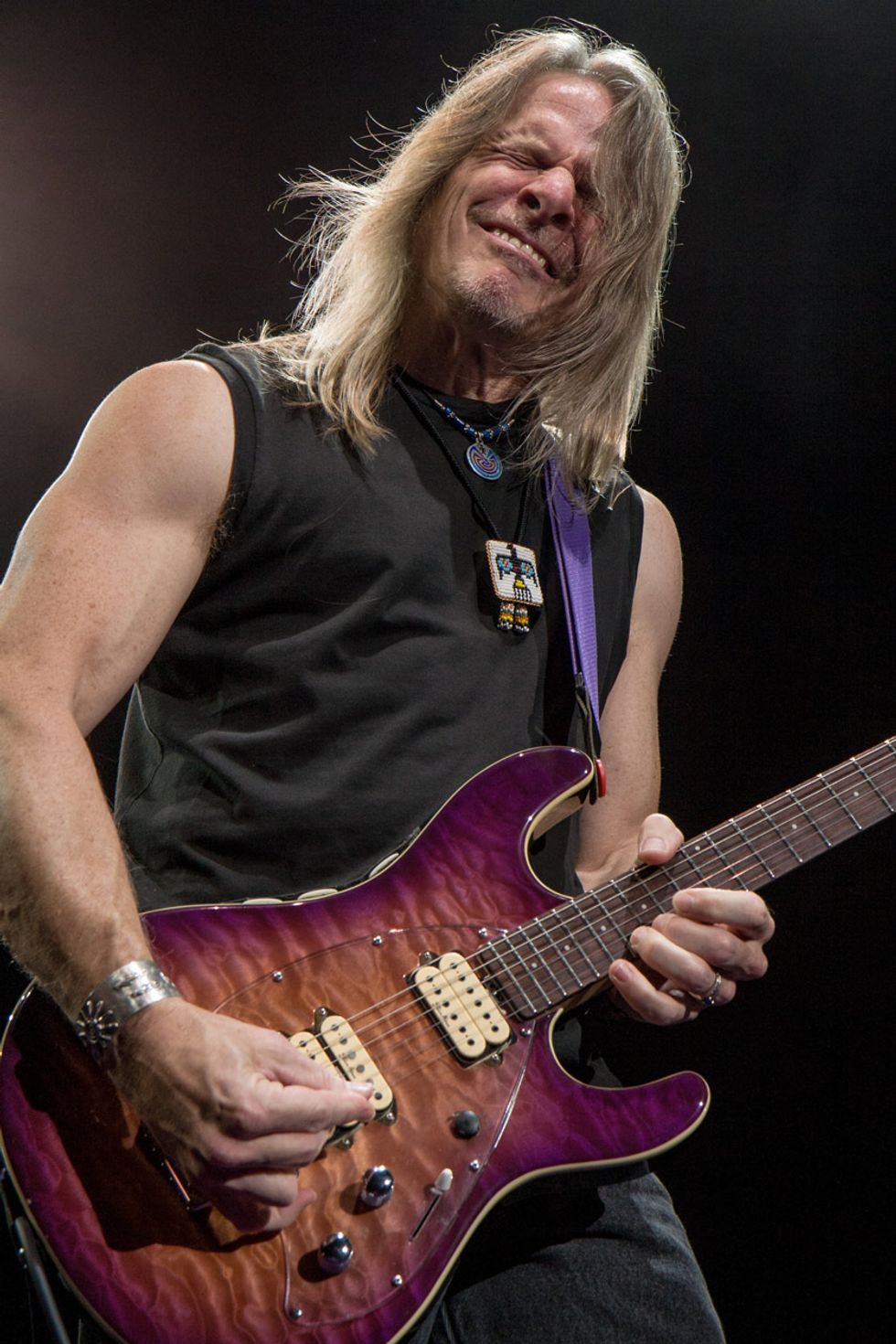

Morse has had his own Ernie Ball/Music Man signature model since 1987. In 2006, the Y2-D pictured here was created with four-pickups and a basic 5-way selector. Today, Morse is playing a new prototype of a 30th anniversary model.

Photo by Tim Bugbee/Tinnitus Photography

In our 2015 Rig Rundown (see “Rig Rundown: Deep Purple’s Steve Morse” on premierguitar.com) you shredded unplugged for a few seconds and the notes were nice and loud. Do you use a heavy attack in your picking hand?

I tend to play with a little too much energy. I’m an inefficient player. I get, like, two miles per gallon.

That’s the opposite of how most guitarists would describe you.

Well, when everything’s just perfect and you’re not pushing it at the very edges of what you can do, yeah, it seems like that’s the best time to catch the most economical picking motions. But when I’m really pushing it and trying to get to the outer edge, it becomes that sort of uneconomical movement.

You’ve switched from heavy to medium picks. What led you to that change?

Just trying to reduce the impact on my right wrist, to make it easier to practice.

Are you experiencing pain in your hands?

Yeah, yeah. I have arthritis in three bones and it’s really advanced. So, every day I practice four different techniques. One is alternate picking with a stiff wrist, because when I play, I tape up my wrist to try to keep myself from using the twisting wrist motion.

So, like a John McLaughlin-type thing?

Yes! Good catch there. And I even hold the pick similar to the way he would, and I practice alternate picking with downstrokes on the downbeats, and then I practice upstrokes on the downbeats, which is very difficult.

Then I switch to my twisting wrist motion to strengthen the muscles. Although it’s very painful, I practice a little bit of that to try to keep the slightly different muscles stronger. Then I practice the swung-eighth picking, where the middle note is hammered or pulled, just because I use that in a section of the set.

And when I do alternate picking, say, sextuplets or two notes per string, I also switch between the stiff wrist and the old way of doing it. I do that with a nylon pick, in fact, when it’s a long way from the tour. When it gets closer to the tour, I switch to the medium picks, which are a little bit more impactful for me. It takes some time to get used to the changing of picks.

How long are your practice sessions? It sounds like you cover a lot.

Every day. Over an hour, but not in a stressful way. I separate my practice from my writing. I can write something and spend hours and hardly play very much. Because I’m thinking, messing with the computer, or bringing up a MIDI part to play along with or something like that.

You’ve used your Ernie Ball/Music Man signature guitars for 30 years now. Anything new in the works?

I’m playing a prototype of the 30th Anniversary model and it’s a different guitar in that it’s got active electronics. It’s very clean, but can also overdrive and really scream. One advantage is when you turn down the volume you still have a lot of clarity and high end.

You recently did the Rock and Roll Fantasy Camp, and I’m sure you’ve come across countless guitarists over the decades. What are the most common weaknesses you see among guitarists?

There are two things: first, dynamics, because lot of bands don’t have a soundman. Realizing that a solo should be at different volumes than the rhythm or background parts. You want to be able to have the solo stand out on its own and the background part far away enough where people don’t want to get away from you onstage.

I’ve heard you mention turning the treble down when the vocals reenter after a guitar part.

Yeah, that’s one thing. I do lots of different things. The other night I noticed I still do that. I hit the low note of a riff that’s ringing, at the same time Ian starts singing so I’ll roll off the tone control. The note still has power and feels like it’s there, but all of a sudden the fizziness or high end that might interfere with the vocals is gone. And I don’t think anybody would notice I’m doing that, but if you did an A/B with both, you would certainly hear the difference.

The second thing I would tell all guitar players is to make more phrases. Put a rest in.

YouTube It

Onstage with Deep Purple, Steve Morse teases the fans with tidbits of classic rock history from “Heartbreaker,” “Fire,” “Crossroads,” “Day Tripper,” and “You Really Got Me” before breaking into “Smoke on the Water,” the band’s signature song.