When it comes to the soulful, funky guitars of the ’60s and ’70s, it’s almost impossible not to think of Curtis Mayfield. Sonically and compositionally, Mayfield set the stage for what many of us associate with slick ’70s funk. However, Mayfield reaches further back than the ’70s and his landmark contributions to the Super Fly soundtrack.

You can find Mayfield’s influence in the roots of Jimi Hendrix’s playing. Listen to “People Get Ready” below. Mayfield’s band, the Impressions, had a hit with this civil-rights theme back in 1965.

Now, check out Jimi’s “Castles Made of Sand” and you’ll notice some immediate connections between the two.

Mayfield had a unique approach to the guitar. He started singing in a gospel choir at age seven and absorbed the music he grew up with like a sponge. He played piano, which his mother taught him, before the guitar. Curtis joined the Impressions at age 14 in 1956. He was noted as being one of the first recording artists to include a strong social consciousness in his music. He was at the forefront of a social movement that would later include Marvin Gaye and Stevie Wonder. Mayfield had a gentle delivery while confronting society with the truth masked from our eyes.

Theory: Intermediate

Lesson Overview:

• Get your hands dirty with Mayfield’s open-F# tuning.

• Learn how to layer funky rhythm parts.

•Understand how to use sixths and fourths to create slippery, melodic fills.

Click here to download a printable PDF of this lesson's notation.

While I was on tour in the Midwest a month ago, our tour manager Brendan McDonough bought to my attention that Mayfield used an odd guitar tuning. I had listened to him for years without knowing this.

The tuning was F#–A#–C#–F#–A#–F# (low to high).

I bet you didn’t see that coming! It’s quite an odd tuning, but it basically translates to an open F# tuning. The tuning was inspired by the black keys on the piano. Once you realize that, it doesn’t seem so weird.

What’s in a Tuning?

One thing that comes up a lot when discussing open tunings is the question of necessity. Many will say that if you’re not using a lot of open-string combinations, it’s not necessary. I can see this point; however, it doesn’t take into account how a tuning can influence your voicing and fills.

A D major chord is not just a D major chord. Where you place that chord and how you arrange the intervals changes the sound considerably. It’s for this reason that you can play the given chords for a song, but still have it sound incorrect because you are using different voicings. A prime example is the music of Bob Marley. His guitar voicings are so tied to his songs. Sure, you can use cowboy chords and get through the song, but it won’t sound like Marley.

I believe the F# tuning Mayfield used greatly influenced his playing. When you listen to a song like “People Get Ready,” the parts flow better with the F# tuning. You can play it in standard, but something just doesn’t sound completely right. For his style, the fingerings flow a little easier in F#.

Let’s look at a few popular scales and chords in the F# tuning, but don’t worry, we’ll get to copping Mayfield’s licks in standard tuning later in the lesson.

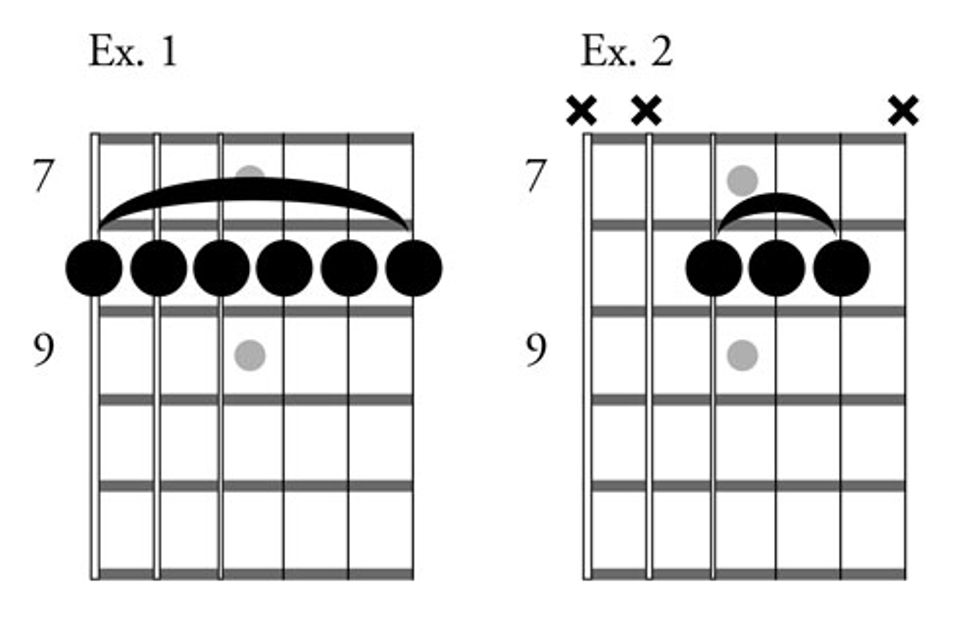

Ex. 1 shows the full D major chord, while Ex. 2 shows a more stripped-down voicing, closer to what Curtis would use.

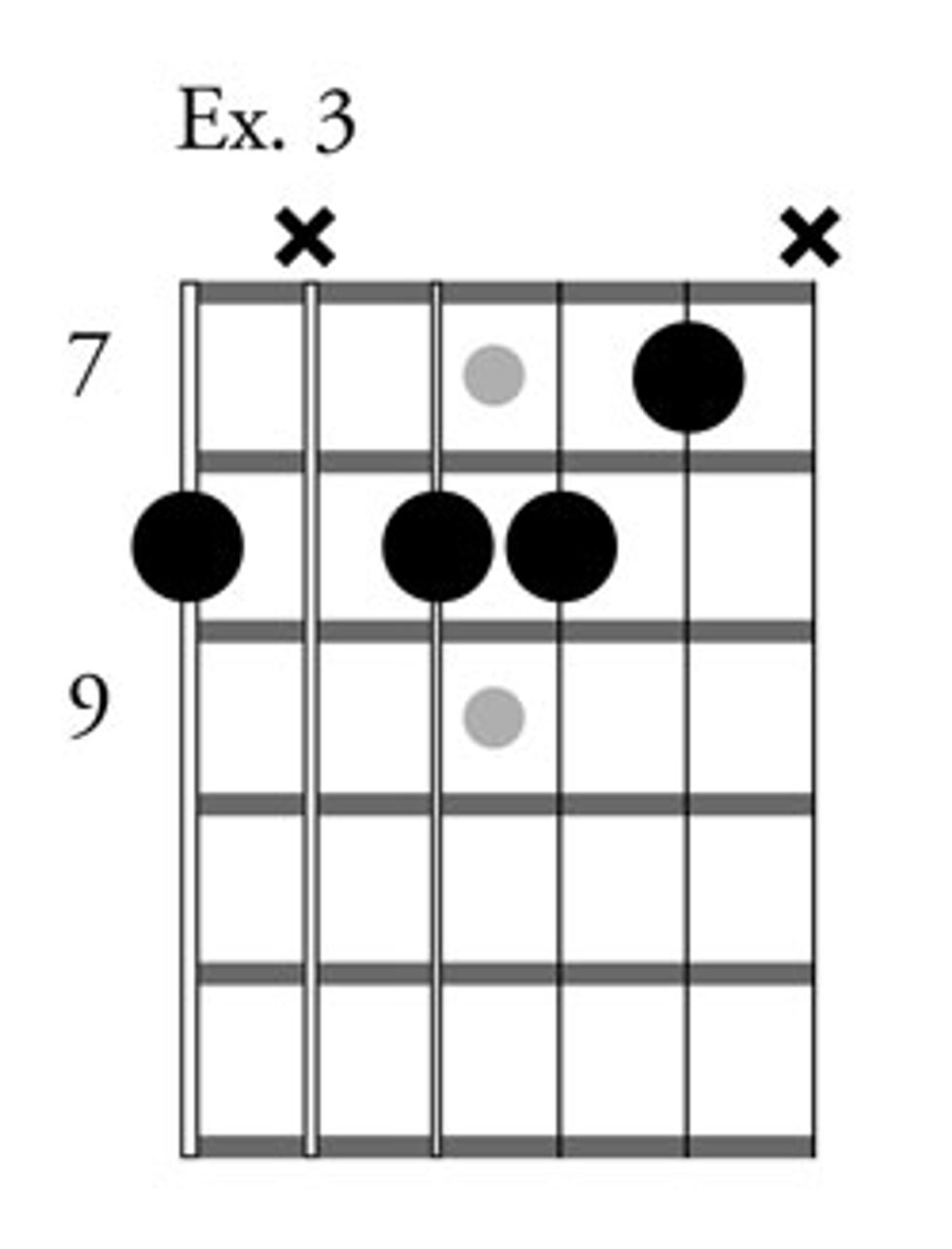

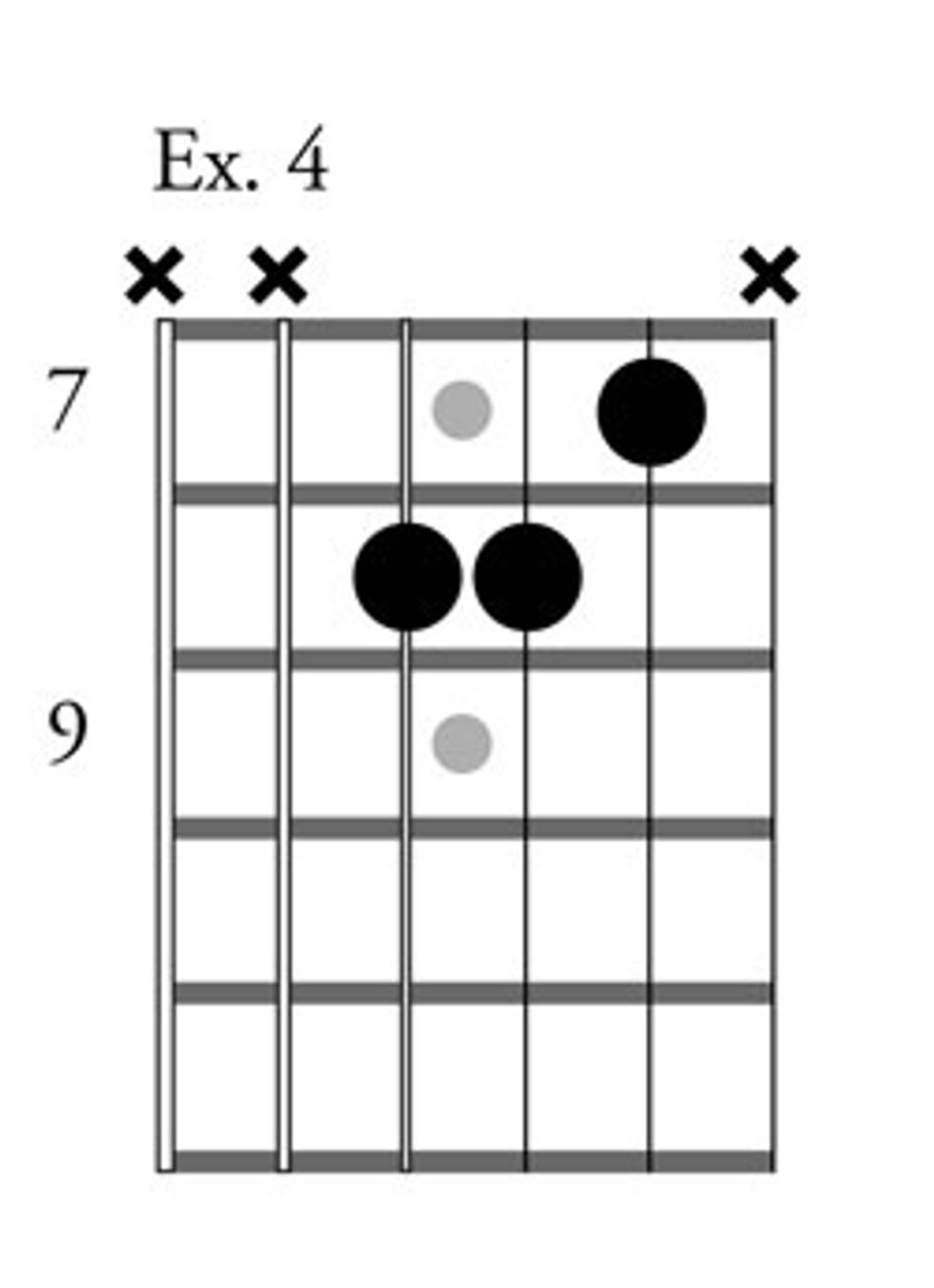

To move from D major to a D minor chord, we lower the 3 (F#) to the b3 (F). Ex. 3 shows a minor triad with a low note on the 6th string. Ex. 4 refines that voicing a bit.

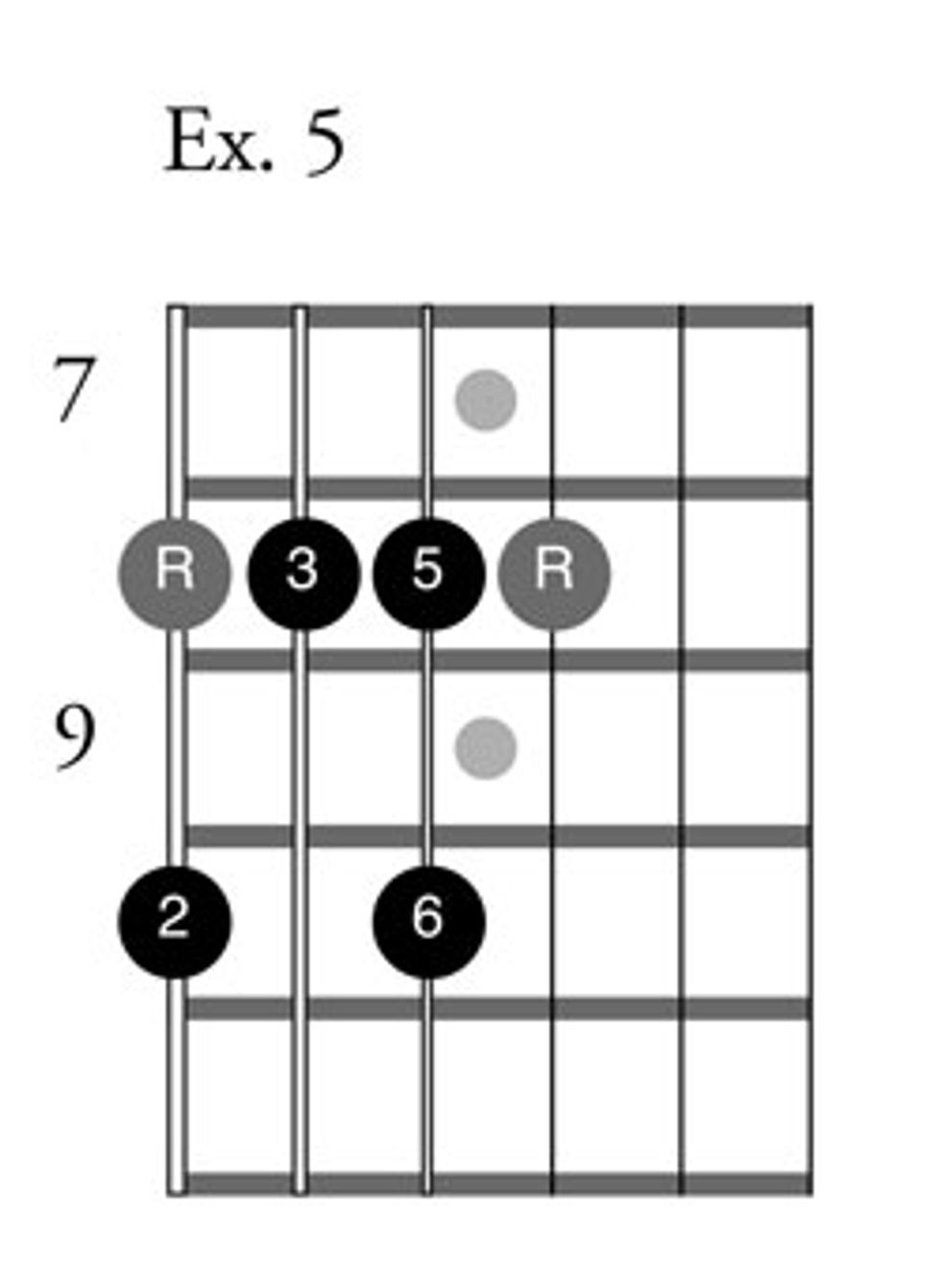

You can see in Ex. 5 that you don’t have to move around too much to add some major pentatonic colors to the major triad shape.

Ex. 6 extends the box to end on the 5th of the scale.

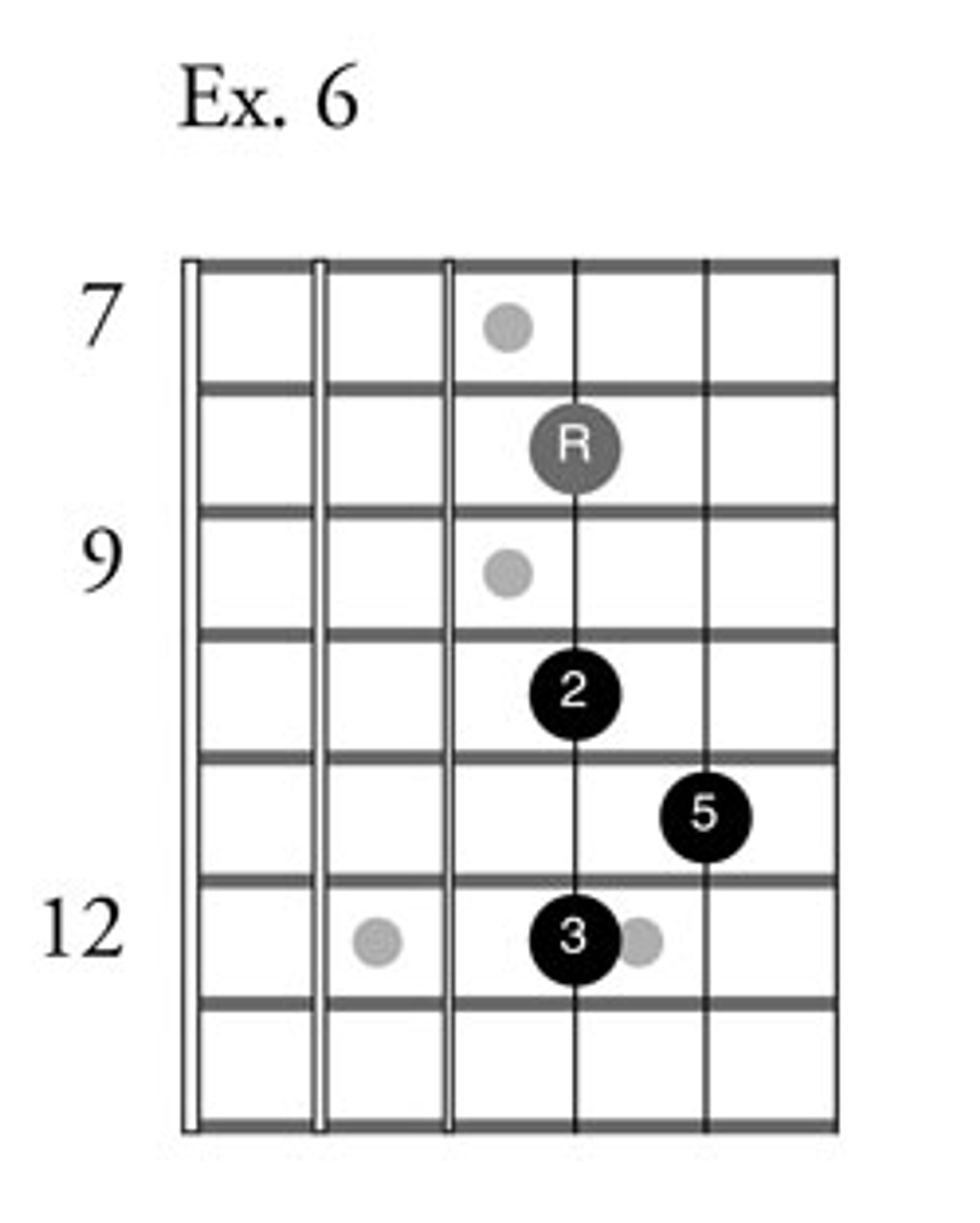

Ex. 7 shows a box for the D minor pentatonic scale (D–F–G–A–C) in the F# tuning. Again, Ex. 8 extends the box ending on the 5 of the scale.

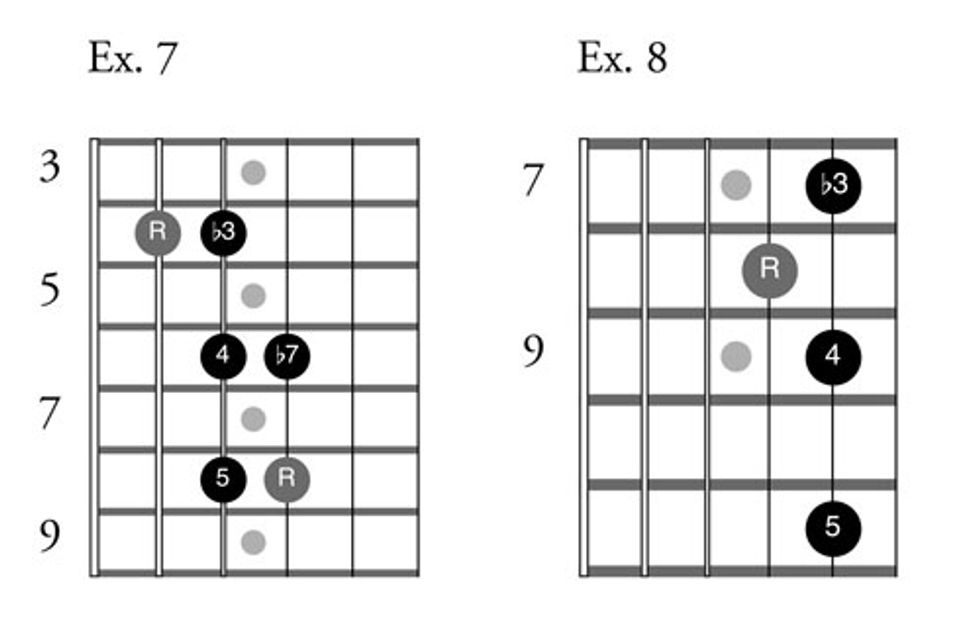

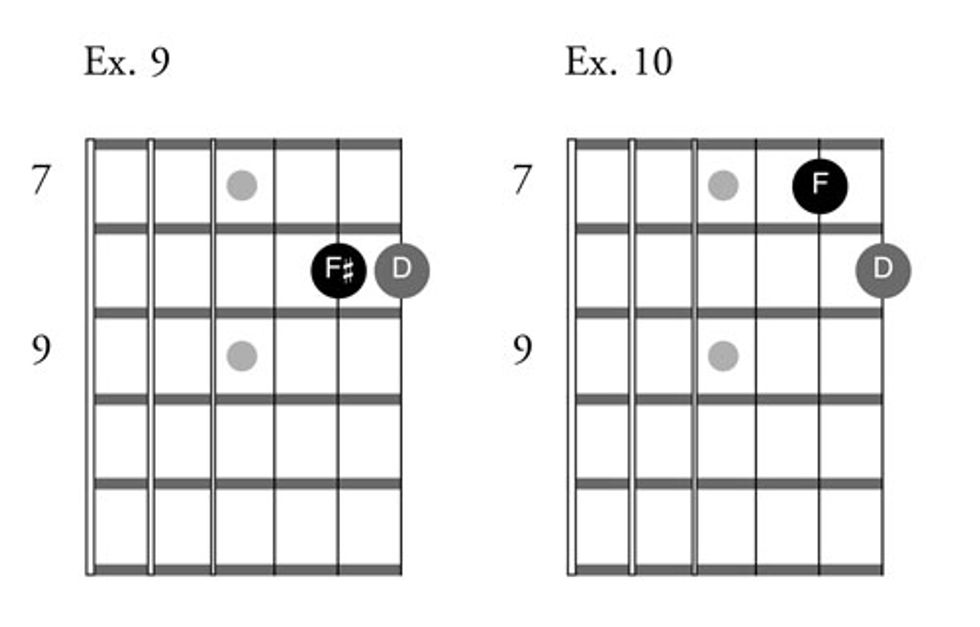

Moving sixths around in the F# tuning is pretty easy. You can play them on the top two strings. Ex. 9 outlines a D major sound from the 3 (F#) of the chord, and Ex. 10 outlines a D minor sound starting from the b3 (F).

Just by looking at these shapes, you can see the convenience of this tuning for coloring chords à la Mayfield. The tuning can influence the performance. However, it doesn’t mean we can’t play Mayfield-inspired music in standard tuning.

The Translator

In this lesson, I’m going to translate his F# tuning moves into standard tuning. It’s not always practical to use open tunings in a live setting. I tend to use them a lot more in the studio rather than live, unless I have a guitar tech and several guitars on tour. It’s not often I can play a whole set in one open tuning.

Let’s get our decoder rings out. Don’t worry, we won’t be drinking any Ovaltine today. First, listen to “Movers and Shakers” below before we dissect Mayfield’s moves.

Stabs

A cool Super Fly-era move would be to play thirds on the 3rd and 2nd strings. I do believe it’s important not to get too fancy with chord extensions. Mayfield liked using simple triads for this effect.

You can try minor or major thirds, depending on the song you’re playing. Either a root–3 voicing or a 3–5 voicing could work. Also, think staccato. In Ex. 11 I only sustain the interval every two measures, which I’m sliding into from a half-step below.

Click here for Ex. 11

Minor Vibes

Superimposing sixths on top of a minor pentatonic riff can create some real vibe. We can use the sixths to imply a minor 6th chord or a minor 7th chord.

One thing to keep in mind is to let these intervals hang for a bit. It’s not about fast movement. In fact, this is an important point with all of Mayfield’s music. It was way more about mood rather than flashy moves.

In Ex. 12 you can hear me play a sixth (G and E) on beat one. This lasts for two measures and helps imply the chord is a Gm6. In measure 3, I play a sixth that implies a Gm7 chord.

Click here for Ex. 12

Double the Trouble

You don’t want to look like a chump. One way to do yourself a solid would be to double the bass line with a fairly clean guitar sound. You can hear this approach on a number of early-’70s Mayfield tunes.

Notice that there is a fair amount of palm muting in Ex. 13. I’m not completely deadening the string, but I am reducing the sustain by about half of its natural decay.

Click here for Ex. 13

Why Don’t You Wah About It?

Playing muted eighth- or 16th-notes with a wah can be summed up in one word: Dy-no-mite! Sure, you can occasionally put a chord in there, but don’t feel obligated to. The muted wah acts like a percussion instrument. When using the wah, you really need to think of your toe and heel position. You can create an inner melody just with opening and closing the wah.

Starting at measure one in Ex. 14, I’m putting emphasis on beats 1, 3, and 4 with the wah in toe position (fully forward). Being that this position on the wah is the brightest, it helps highlight the beat. Take note of the slow sweep on beat 2 that builds into beat 3.

Click here for Ex. 14

What’s Mine Is Yours

Hendrix borrowed many sonic concepts from Mayfield. Let’s look at one over a minor 7th chord (Ex. 15). I like to think of it as the 5 of the chord is the lowest note, then simply playing the root on top which moves down to the b7. Also, listen to the second half the first measure in the song “Transit” below.

Click here for Ex. 15

Fourths

Fourths get neglected in modern times. Importing some fourths into your soul tune can grease the wheels, if ya’ know what I mean. Can you dig it?

In Ex. 16 we’ll slide some fourths from the 2 of the scale up to the 3 of the scale. This works great over major chords. Makes sense when you think about it. We’re essentially sliding into a chord tone (3) with a harmonized fourth above it. In Ex. 17, I move the concept down a string set.

Click here for Ex. 16

Click here for Ex. 17

Five Plus One

Mayfield didn’t invent slick moves involving sixths. It can be traced back quite far in the blues and soul library. He did make tasteful use of it, though. I incorporate it over the I chord to sweeten the tea a little in Ex. 18.

Click here for Ex. 18

Don’t Show All Your Cards

One thing to note about Mayfield is that he was a master at refining parts. He didn’t use every trick he had in one song. He thought about parts. Nuance was key. He was far more concerned with creating an overall vibe to a song. His choices were textural and he didn’t fill every crack. This is a challenge for most guitarists. We often feel the need to fill every space. You’re going to want to let things breathe.

Tie into Your Own Thing

Personally, I like to see how I can implement some of these ideas into songs I’m already playing. Dust off the cobwebs from songs you have in mental storage. Let’s pull them out to see if we can shift the vibe slightly with these new approaches.

It’s going to take some time for these concepts to seep into your playing. Avoid the crash course method. Let the ideas steep like a nice cup of chamomile tea on a chilly autumn evening. Spending five minutes a day on each of these concepts will help you develop consistent growth. Within one or two months of somewhat regular practice, you’ll start to see these flavors emerge naturally in your playing.