Jeff Tweedy has elevated the art of songwriting in the American tradition during his 32-year-long career—first as a cofounder of Uncle Tupelo, and then, since 1995, as the leader of Wilco. Both bands were planted firmly in the roots music tradition, drawing on folk, rock, psychedelia, blues, gospel, and other pages in the songbook of history. And today, Wilco is an ambitious group that straddles the terrain of the Byrds, the Band, Coltrane, Pops Staples, the Minutemen, and Pink Floyd—in a balance that fluctuates from album to album and, sometimes, song to song.

Throughout Wilco’s evolution—over the course of 10 studio albums, a double live set, and collaborative recordings with Billy Bragg and others—Tweedy’s songwriting has been the nucleus of the band’s music. It is marked by poetic yet relatable introspection, and wit that’s sharp and wry. Tweedy’s gifted pen has earned Wilco seven Grammy nominations, including a win for Best Alternative Music Album for 2004’s A Ghost Is Born. But Wilco has typically operated as a unit when it comes to arranging songs, and has benefitted especially from the talents of a pair of bona fide virtuosos: lead guitarist Nels Cline and drum phenom Glenn Kotche. The group leaves a distinctive sonic thumbprint, with whorls that bear the character of all six of its members.

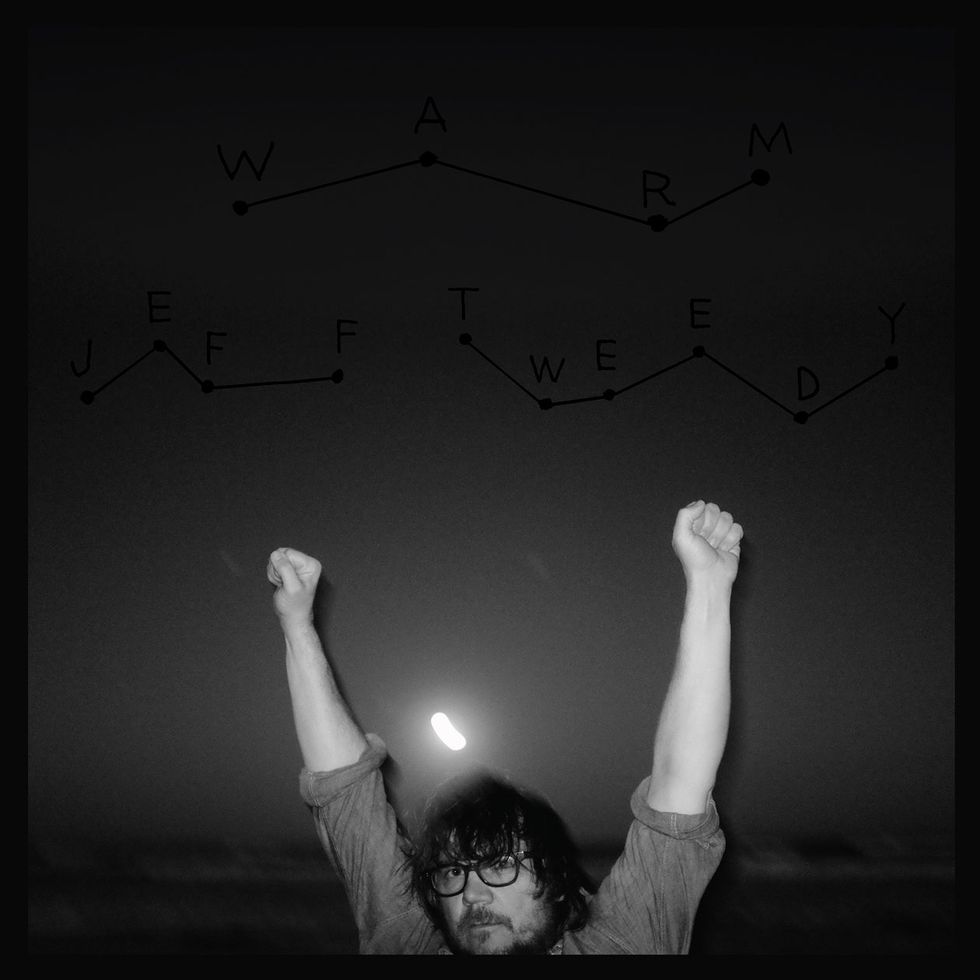

Now, with his new debut solo album, Warm, Jeff Tweedy emerges for the first time as a musician truly carrying the full weight of his own art. It follows 2014’s Sukierae, an album he penned and tracked with his son, Spencer, on drums, under the Tweedy moniker, but Warm is unadulterated.

Longtime fans already know Tweedy as a fervent champion of the guitar and an excellent player in his own right, but he’s typically abdicated any fireworks on Wilco’s albums to Cline since the guitarist joined in 2004. “I’m a passionate guitar lover,” Tweedy explains, “but I’ve always hesitated to spend too much time talking about my playing, because I don’t feel particularly insightful or like I have any kind of interesting technique to share. It’s much more philosophical for me than it is for Nels—even though Nels is a deeply emotional player and not just some mathematician or something.”

The truth is, Tweedy sells himself short as a player. Any doubt that he has a unique voice on the guitar should be quelled by Warm. Its sparse arrangements are built around his rock-solid acoustic rhythms and laced up with clever faux pedal-steel bends and delicate, creative passages on electric guitar. And speaking of guitars, anyone who’s seen a photo of Wilco’s legendary Chicago headquarters/studio the Loft can attest that Tweedy is a gear fiend, with a treasure trove of rare, vintage, and just plain cool guitars, amps, and more lining the walls. Nonetheless, the list of equipment used to track Warm is spare, although it includes rare vintage items like his beloved 1930s Martin 0-18 and an Italian Wandre Polyphon Beta.

PG recently spoke with Tweedy about creating Warm, his guitar passions (which include a love of dead acoustic guitar strings and top-loading Telecasters), and how he found the confidence to simply be himself as a musician.

You own an incredible collection of rare guitars. Were any of them particularly important to writing the solo album?

Not so much on the writing end, but I recently got a ’58 whiteguard Fender Esquire with a top-loader bridge that I tracked most of the electric guitar on the record with, so that was a pretty important guitar for this album. It suits my playing a lot better than other Tele guitars for some reason. It’s just that much more responsive.

I found it to be a lot more dynamic than some of the traditionally configured Teles I have, and I’ve never really had an Esquire to do an A/B with my other Teles before. I was kind of shocked by how much more I took to the Esquire, because I love a lot of my Teles and I’m not particularly against any guitar, to be honest, but it really opened up some of the fake pedal steel that I hadn’t really done before.

You don’t speak much about your background as a player.

I don’t have much technique to rely upon, so I’ve shied away from doing many interviews about guitar playing, specifically. But I do love it and I do work at getting better. Not necessarily at scales or the traditional things that people use to measure their aptitude as a guitarist … but I work hard to be able to play what I want to hear.

I had a revelation a while ago, when I was beating myself up at some point. A lot of guitar players are measured by how well-rounded they are these days. Can they comp jazz chords? Can they do Albert Lee licks? Guitarists seem to have to have a pretty big tool chest now, but my favorite players—like Hubert Sumlin or someone like that…. He was never measured by whether or not he could emulate anyone else’s style! He was simply Hubert Sumlin, you know? That revelation has given me a lot more confidence to just turn that side of my brain off and focus on communicating with my tools.

I love talking about guitar, I love tone, and I love getting it to sound the way I want it to sound, but at the same time, I’m not overly precious about it. I do believe a performance has much more to do with why things sound good than a lot of people are willing to give it credit for. I find it really funny when people try and chase down the exact gear someone used to get a sound—when they feel like they absolutely need to cop that tone.

TIDBIT: Tweedy played all the guitar and bass, and much of the drums, on his solo debut. “I found it really invigorating to be forced to confront my limitations and see how close I can get to something that I’m hearing in my head,” he observes.

There’s a whole industry built around providing that for people, but the fact is that most of those people making these classic records were just using whatever they could get their fucking hands on, you know? You want to sound like Link Wray? I think you should play like Link Wray on whatever gear you can afford or find. One of my favorites is Nick Drake, who has a Guild M-20 on the cover of Bryter Layter, but I don’t think he ever played that guitar! There’s an example of a guitar that shouldn’t be hard to find, but has become hard to find probably in part because of that record cover.

Despite that, you and your cohorts in Wilco have amassed a truly incredible collection of gear. Did you experiment much with guitar tones on this album, and is option fatigue ever an issue when you have so many choices?

I can remember what combinations of things we own sound like, and I really surprise myself when we go back to recordings that we started three or four years ago and I remember specific combinations that were on each track, and stuff like that. I have more of an aptitude for that than playing scales. I really enjoy the process of getting sounds, but I also really prefer to move quickly, and it’s more important to me to get a sound that’s inspiring as opposed to going for the best sound.

For all of the gear that’s at the Loft, I use a shockingly small amount of it, except when I have to recall a specialized thing that I’m aiming for. I go through periods where I’m really into a specific setup, and for the last couple of years, it’s been a Princeton Reverb. For the most part, I’m pretty content to have this unadulterated, badass signal path that I know is going to, at the least, allow me to get an idea down quickly. If it needs to be something more elaborate or I feel like I need to make some kind of specific sonic statement, then I’ll start plugging things into the chain and playing around with that sound. For a couple of years before I got into the Princeton, I was using a Fender Champ almost exclusively and that’s all the sounds on [Wilco’s 2015] Star Wars and the Tweedy record.

For the general process that I’m enjoying at the studio these days, I’m permanently set up and ready to go with a sound that I really love, but then there’s all of the gear we have. That’s a collection, yes, but it’s more about it being an inspiring, working set of tools. That’s the predominant reason why, when you see pictures of the Loft, there’s so much gear out and available. It’s important for me to be able to have that spontaneous moment where you walk by something and put your hand on it for no reason, and the next thing you know, you’ve picked it up and been inspired to play something. I think it’s something in the subconscious that inspires you to pick up a particular instrument, for whatever reason it’s speaking to you that day. That’s the kind of work environment we’ve tried to foster at the Loft—just having these tools out, handy, and available to everyone.

Would you mind walking us through your core signal path on this album?

It’s mostly that top-loader ’58 Esquire straight into a silverface Fender Princeton Reverb. It’s not a drip-edge model, but I don’t know the specific year. I used an AEA N22 ribbon mic, for the most part. I know that amp really well, and where it drives in a way that’s pleasant to my ear, and I’ll sit on the couch and play and hear it through the studio monitors. For certain songs, I’ll adjust settings on the amp to get what I want out of it. It really is super straightforward.

The bedrock for Warm was Tweedy’s 1930 Martin acoustic with absolutely dead strings. “Sometimes I have to change the high E and B strings because they stop being intonatable when they get super, super gross,” he says. “But the rest of them are just disgusting. They’re horrifying and no one else in my band wants to pick up my guitar.” Photo by Tim Bugbee

The bedrock of the album is acoustic guitar. What did you use?

My main guitar for years has been a ’30s Martin. I’m not sure what the specific year is, but it’s an 0-18 and it’s pretty beat up. It’s been broken and put back together a few times. It still has the original bar frets. There’s not much left to them, but I’m really dreading having to make that change, and I’m going to put original bar frets back in it when I do refret it because I’m just so used to it.

Do you use specific strings to make it playable, with those old, small frets?

No, just dead strings. [Laughs.] I never change strings unless I absolutely have to, so it’s honestly been so long that I don’t know what’s on it. They’re most likely D’Addario, because we’ve been getting strings from them for so long. They’re fairly light gauge, because it’s such an old guitar and seems to respond better to a little bit lighter gauge than I’d put on some of my other guitars. But not super light. Sometimes I have to change the high E and B strings because they stop being intonatable when they get super, super gross, but the rest of them are just disgusting. They’re horrifying and no one else in my band wants to pick up my guitar.

Why do you prefer dead strings?

It creates a guitar that’s somewhere between a classical and a steel string, to my ear. It has a more narrow spectrum of overtones, which can get in the way, for me. I always feel like my singing voice is being upstaged by a new guitar that rings like a bell. My singing voice is like a frog or something, you know? I don’t want to put that up against this pristine-sounding instrument. I’d rather have an instrument that feels and sounds a little downtrodden.

Is your songwriting approach for a solo album different than how you write for Wilco?

It really doesn’t change that much. I don’t ask much of myself when I’m in the writing phase of things. I just like making stuff. I try and stay in a frame of mind where there’s a minimal amount of judgment going on, from my observing ego or whatever you want to call it. I really love making songs up and I’m in a fortunate position where I have a studio and a lifestyle that allows me to come to the studio every day and make stuff up, so I accumulate a lot of material. The process from there is really, “can I put these songs across by myself?” That was the primary concern with putting out a solo record. The genesis for most of this material has been the same for a long time.

Did you enjoy handling all of Warm’s guitar?

I found it really invigorating to be forced to confront my limitations and see how close I can get to something that I’m hearing in my head. In a lot of cases—especially on this record—I had to really take the time to teach myself how to do things and learn what bends would create the effect I was looking for, like a pedal-steel part. I know I don’t get it right always, but it’s exciting. When people misread things and I play my idea of a pedal-steel part, not an actual pedal steel, in a lot of ways that’s more emotional than hiring the hot-shit pedal-steel player and having them do their best shit, you know?

It’s a different process when Nels and I get together to work on Wilco songs, and it can actually be kind of daunting having the amount of options an incredible player like Nels brings to the table. It can be a struggle sometimes to narrow it down to what exactly you want to hear, so it ends up being a much different process for Wilco.

You’ve spent a long time working with Nels. What have you learned from that?

Playing with all of the guys in Wilco—and especially Nels and Glenn, who have really solid music backgrounds and read music and understand theory—has made me a lot better as a player. It’s made us all better, when it comes to working with each other. I can transpose and I can do a lot of things now that I would’ve had to really hunker down and learn how to do at some point in my life, but I didn’t. I feel pretty confident about a lot of those things now, and they’re not really so specific as learning an exercise or something from Nels that changed my life. It’s more osmosis, from just playing with really great musicians. I think the main thing that I’ve gotten from Nels, to be honest, is enthusiasm and encouragement for my playing. He’s such a champion of the way that I play. Maybe it’s because it’s so different from his own approach, but Nels is always validating me and telling me really heartfelt, sweet things about what he likes about my approach to something on the guitar or as a songwriter, and he’s just a great guy. That alone has given me so much more confidence to be comfortable in my own skin and continue to do what I’m doing.

That being said, one of the nice things about Wilco is that everybody wants to get better. We’re all always trying to get better! It’s so much fun to get better, you know? I think it’d be really awful to think that you’d figured out how to do everything you want to do on an instrument. My relationship is much more still playing with it to try and figure out what it can do in my hands, as opposed to maybe setting up a philosophy that forces me to stop exploring.

Guitars

1930s Martin 0-18

1958 Fender Esquire (top-loader bridge)

1960s Wandre Polyphon Beta

Fender Mustang bass (Alembic pickups)

Amps

1970s Fender Silverface Princeton Reverb

1960s Fender Champ

Effects

Fairfield Circuitry Shallow Water

Strings and Picks

D’Addario EPN21 (.012–.051; unwound .020 replaces the wound .23)

Custom Wilco-branded Dunlop Herco Flex .50 mm

How has working with your kids changed your approach?

Spencer and [vocalist/photographer] Sammy both listen to tons and tons of music, but I listen to tons of music, too. I’m pretty insatiable when it comes to that, and I’m always looking for new records to be excited about. That’s the way I lived my life, and outside of being a musician I think I’d still be doing that. Something really thrilling about being alive is people making shit and getting to enjoy it.

Playing with Spencer was a huge revelation. He’s kind of like Nels or Glenn. He’s a savant. He’s such a natural musician compared to me and he’s very patient with his dad and teaches me things all the time, but he’s still growing as a performer and a person, trying to consistently get what he wants out of himself. Aside from those things, which I can maybe teach him, his overall ability and aptitude is through the roof.

I love the arrangement of “I Know What It’s Like,” from Warm. Would you walk us through that track?

Yeah! It’s that Martin 0-18 as the acoustic bed, and there are a couple of layers of bendy Fender Esquire with the reverb turned way up on the Princeton to approximate a pedal-steel sound and add texture, and then there’s a couple of doubled parts played on a rare ’60s Italian-made, aluminum-necked Wandre Beta, which was played through a Shallow Water pedal, made by Fairfield Circuitry. That pedal is weird and makes everything sound like it’s on warbly tape. There are a lot of pedals that do that, but this is the one that sounds really musical, to my ears. That’s the warbly chorus thing going on in the back that’s almost a little new-wave sounding.

Those old Wandres are such wacky, interesting guitars, but never particularly inviting to play, in my experience. What drew you to that Wandre?

It’s not really a guitar, right? It has this texture you can’t get from much else. It’s between a guitar and a banjo, and I don’t know why it’s so appealing to me, but it’s all over the record. All of the little detail things that you hear on the periphery in the stereo spread is mostly the Wandre.

The arrangement and tuning on “The Red Brick” are interesting, too.

The stuff that sounds like a banjo is the Wandre, and the backwards desert blues kind of thing is the Esquire, and there’s one guitar that’s got most of its strings tuned to C and it’s droning. Then there’s one more guitar that’s in standard tuning that’s playing a riff that kind of takes it out of the key of C and makes the song a little more ambiguous sounding.

What bass is on that track? It sounds interesting.

I have a Fender Mustang bass that has Alembic pickups. It’s a real oddball, and I haven’t been able to find anything else that sounds like it. This is what ends up happening with a lot of my gear. If I develop any kind of relationship with it, I can’t get rid of it. It’s just a weird, kind of crappy Mustang bass, but with those Alembic pickups, it sounds monstrous through a Fender Champ, and that’s what you’re hearing on that song.

My favorite fuzz tone is from one of my Fender Champs that has a replacement speaker in it that I’ve never seen before. I think it’s from an intercom or something. It shouldn’t be in a guitar amp and wasn’t meant for that kind of power. For some reason, it sounds like the most incredible, gigantic fuzz tone, and everybody always asks what pedal I’m using when I play through that amp.

You’ve always had a real strength for adding interesting parts and nuanced adornment without losing the plot of a song. Any advice for singer-songwriters looking to do the same?

You shouldn’t be too precious about things. You can come up with the greatest part in the world and it might not make the song better. I’m constantly backtracking. I’ll put something on a song and live with it for a few days, and I’ll always make a point to go back to where I was before I made the transition to that different landscape and ask myself if it really made it better, or if it was better before—when it was more sparse. I’m not indecisive at all, and there are times when I just know that I’ve transformed something into something better. I think a lot of people just keep adding because they assume that’s the direction you’re always supposed to be moving in, but I think that it’s really important to backtrack from time to time.We have a phrase for it: “That’s a cool part, but it won’t affect sales.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.