The idea of branding has become the mantra of every type of business endeavor. As consumers, we often refer to our gear in terms of the brand that produced it. Once just a byproduct of good, consistent manufacturing and sales, branding is now the catchphrase for a calculated and concise series of marketing tools that businesses use to promote their moneymaking efforts.

Years ago, businesses could be divided roughly into two camps. There were businesses that made or sold goods and services, and then there were brands. The corner hardware store was an example of a business, and Ace Hardware an example of a brand. The first sells you nuts, bolts, mops, and garden hoses, while the second sells you the promise of being a helpful place to shop for that stuff. If you think this sort of distinction doesn’t work, consider that Ace is the world’s largest hardware-item cooperative. So, which came first, the branding or the brand?

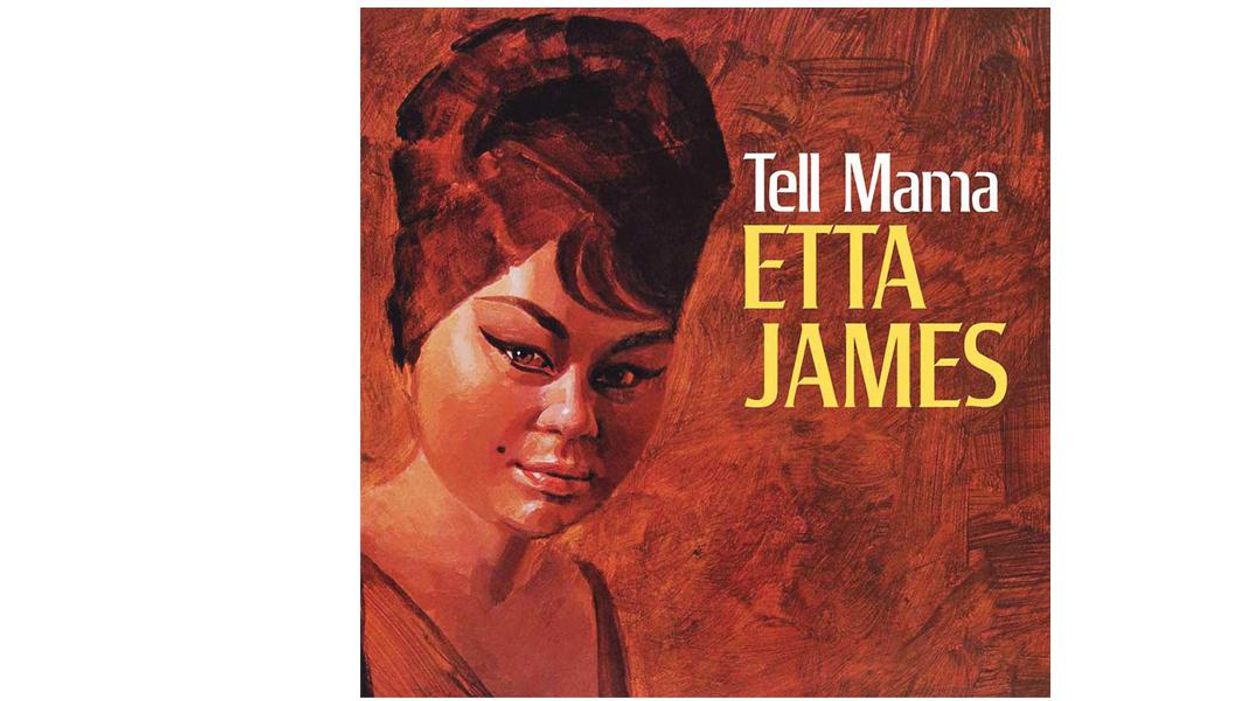

When I started playing guitar, I quickly became aware of the idea of brands. Each guitar and amp type had a name that stood for its place among the galaxy of musical products. Intrinsically, my young mind started to make associations based upon visual cues such as advertising, record jacket photos, television appearances, and magazine articles. The human brain tries to make sense of what it encounters, and, therefore, I began to categorize products.

Gibson guitars were for old men who wore suits and played jazz. Fender guitars and amps were for dudes who surfed and drove hot rods. Gretsch seemed to straddle the ground between British mop-heads and country pickers. The cheap brands I saw when my family shopped at department stores were mainly Silvertone, Harmony, and occasionally Supro. These I knew were for beginners. I was vaguely aware of the off-brands like Guild and Kay, but they just didn’t figure into my early guitar lust, because my heart belonged to Mosrite, the King God of instrumental twang. Acoustic guitars? They were for hillbilly music and almost beneath contempt.

In retrospect, I can understand my thinking, but what amazes me is how little I understood about the design and manufacturing realities behind the names. This demonstrates the power of brand loyalty. You could have told me that Semie Mosely had killed Kennedy, and I still would have wanted that Mosrite.

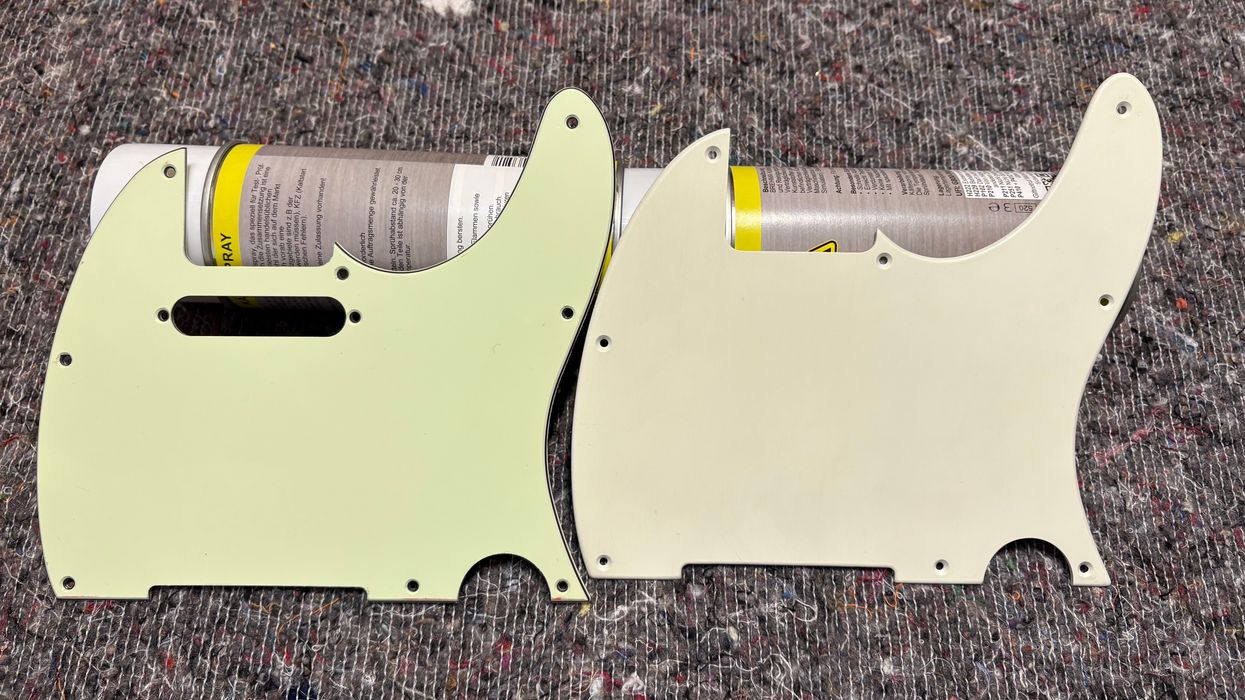

Today, there are more builders of guitars, amps, and effects than ever before, with each one attempting to stake a claim in the impossibly crowded landscape of the MI business. For better or worse, we have a huge number of options, and sometimes it’s hard to dodge through the hailstorm of publicity for products that basically all do similar things. When you are shopping for butter, the choice is pretty simple. Attempting to pick out a pedalboard switcher, however, can be like planning a wedding—a lot of handwringing for not a whole lot of return. So how does a builder, artist, or even a retailer build a brand? And even if they do, will it matter? When everything and everyone is a brand, is anythinga brand?

Most any course in marketing will outline the steps you need to take to construct a brand. First, create a logo, and then stick it on everything. Never mind if it’s a good logo. (Apparently this doesn’t matter.) Next, create a tagline for your brand. A tagline is what tells your potential customer who you are and what they can expect from your brand, something like: The World’s Most Awesome Guitar Pickups. This will set your product apart from competitors and also remind you and your employees of why you exist.

This leads us to your mission statement, the credo that your brand lives by and must always live up to. If you are a design-based brand, your mission statement might be something like: We will always be at the bleeding edge of dope design, and pledge to deliver the most fashion-forward guitars for our customers. Having a well-thought-out mission statement will help you at every step of the way. For example, when you are contemplating designing a new product, you can step back and ask, “Does this represent the most dope, fashion-forward design statement we can make?” If it does, you’re cleared for takeoff. If not, go back and start over. This way, your customers will know what they are signing up for, and that creates brand loyalty.

You see, it doesn’t matter what direction you choose with your product. It doesn’t matter where you make it, or even what it sounds like. Brands are free to be manufactured in a giant factory in China or assembled from parts by a novice in a suburban garage. That’s not the point, especially if you have hats and t-shirts. The internet can spread your message instantly, so pick a brand identity and get going. It only matters that you remain true to it. “Hey, get off of my lawn,” is my mission statement. And it seems to be working.