No matter what’s happening around him, you can bet safe money that Willie Nelson still can’t wait to get on the road again. From the confines of his Luck Ranch on the outskirts of Austin, Texas, he’s trying to make the most of the conditions that forced him to cancel the remaining dates on his spring tour and delayed the release of his latest album, First Rose of Spring. But after speaking with him for just a few minutes, it’s pretty clear that nothing, not even a coronavirus pandemic, will keep the ever-resilient country music hero from staying focused on the future.

“I mean, for now we just have to work with what we get,” he says matter-of-factly in his amiable, zen-like drawl. “We’re up in the hill country, and everybody seems to be pretty healthy, so we’re just trying to keep it that way. But we have a few things we’re planning online, and then I’ve been going in the studio every day since I’ve been here. I have a lot of stuff happening with Micah, my son—he’s recording some. We just need to have something to do, because you can’t do nothing else, really.”

By the end of April, Nelson and his family production team had hosted four of his Luck Presents events from the ranch, including the annual Luck Reunion, which normally draws 4,000 fortunate fans to Nelson’s property for a day-long music festival. It was quickly reconfigured as a livestream called “‘Til Further Notice” and aired on its originally scheduled date of March 19. In the closing highlight, Nelson sat in his living room with his two multi-talented sons, Lukas and Micah, to play a freewheeling acoustic rendition of his longtime live staple “Whiskey River.” And a few weeks later, the three convened again to perform “Hands on the Wheel,” from Nelson’s classic 1975 breakthrough Red Headed Stranger, for his long-running Farm Aid benefit.

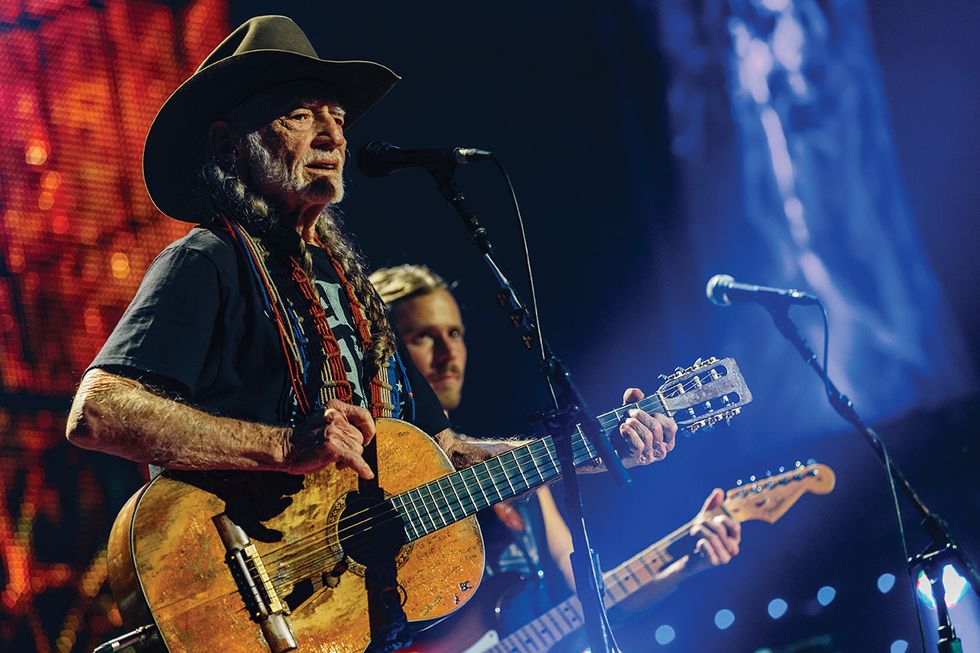

Under the circumstances, it’s a treat to get a glimpse of the Nelson family at home, but it’s also a painful reminder of what we’re missing. Willie Nelson in concert is more than just a performer. He’s an experience unto himself: a walking, talking wellspring of country, soul, blues, and jazz lore, and a profoundly gifted interpreter of music who can take a crowd of 70,000 people on an emotional journey that lingers for the rest of their lives.

There’s a bittersweetness, a sweeping sense of nostalgia, in that notion, which Nelson captures perfectly on First Rose of Spring. Produced by longtime friend and confidant Buddy Cannon, who has helped craft Nelson’s sound—and co-written a growing number of songs—on some 15 recordings going back to 2008’s Moment of Forever, the album is as much a statement of love, hope, reflection, and, yes, house-rocking and hell-raising, as it is a solemn and intimate portrait of a man fondly looking back over a life that’s been lived to the fullest.

Of course, the title song pretty much says it all. “First Rose of Spring” is first and foremost a sweet love song, and finds Nelson singing with unusual tenderness, clarity, and strength, while the brief solo he takes on Trigger—his instantly recognizable road-beaten Martin N-20 nylon-stringed acoustic guitar, which he acquired new back in 1969—crackles with the sound of Texas blues and flamenco-flavored Mexican folk, all imbued with Nelson’s confident touch and quirky, fleet-fingered licks.

“I just love Willie’s guitar playing,” Cannon says from his home just outside of Nashville. “Every time he plays Trigger, he plays something different. I mean, he even surprises himself. Sometimes he’ll play something and he’ll laugh, you know? Everything is improv with him. He doesn’t sit and think, ‘Hey, how about this lick? Let me work on this and get it right.’ He never plays the same thing. You can play the same song, same track, 10 times, and everywhere he places a note is different every time—and to me, it’s all correct. It’s never wrong.”

Nelson might wave off the praise, but it’s clear that he trusts Cannon implicitly in the studio. “Buddy and I just work really well together,” he says. “He’s in Nashville, and I’m usually somewhere else, so he’ll cut the tracks in Nashville, using the musicians he likes to work with, and then when things are ready, normally he’ll come down here to my studio. Then I’ll just go in and do my parts. It’s really an easy way to record.”

It’s also testament to Cannon’s talents that he can make the album sound like it was tracked with everyone in the room together [see sidebar, “Trigger Happy:Buddy Cannon on Recording with Willie”]. “Blue Star” and “Love Just Laughed,” in particular, both new songs that Nelson co-wrote with Cannon, stand out for the way Trigger meshes in the mix with the harmonica licks of longtime band member Mickey Raphael, as well as the buttery steel guitar played by Mike Johnson, and the lush Fender Rhodes (on “Blue Star”) by keyboardist Catherine Marx.

Nelson plays through a vintage Baldwin C1 Custom amp, which accents the lushness of the Martin while also giving it a unique bite that responds to his touch, and can cut through any wall of sound, depending on how hard he plays.

TIDBIT: Willie Nelson’s 70th solo studio album, First Rose of Spring, was produced by Nelson’s longtime collaborator, Buddy Cannon. Most of Nelson’s vocal and guitar takes were tracked at his Pedernales Studio in Texas, with Steve Chadie engineering. Additional sessions were at Nashville’s Blackbird Studio with Cannon’s trusted engineer, Tony Castle.

For all the ballads on First Rose, Nelson still went for what he says felt right, from the campfire-like mood of Chris Stapleton’s beautiful “Our Song” to the honky-tonk groove of “I’m the Only Hell My Mama Ever Raised,” made famous in 1977 by none other than Johnny Paycheck. “Me and Paycheck were good buddies,” Nelson says, “and I loved what he did on that record. But yeah, I just picked what was available and did pretty much what I wanted to do, you know? I think that’s the way it ought to be.”

Nowhere else does that intention come through more forcefully than on the album’s closer, “Yesterday When I Was Young,” made famous by the late Roy Clark back in 1969. Nelson seems literally to feel the song in his bones, while his picking of the main melody and plucking of the underlying chords conjures visions of Django Reinhardt (one of his childhood heroes) laying back on a classic ballad like “September Song”—complete with a string section to heighten the sanctified mood.

Of course, Nelson is fully conscious of the song’s implications, since it’s such a moving and heartfelt way to close the album. “I thought so, too, and I’m glad you agree,” he says. “I remember hearing Roy Clark doing it a hundred years ago. He really turned me on to that song, and I’ve loved it ever since.”

He pauses to consider the memory. Having just turned 87, and having lost so many close friends in recent years—including his longtime drummer and best friend Paul English, who passed away in February—Nelson can be forgiven for sounding a bit sentimental. The thing is, a sense of vulnerability is part of what makes his music so accessible. From his country standards “Crazy” and “Funny How Time Slips Away” to his latter-day hits “Always on My Mind” and “On the Road Again,” a palpable warmth, openness, and humanity runs through everything he’s ever recorded.

Nelson also took naturally to the ethos of the “outlaw” country sound that he’s credited with helping to invent. After all, his penchant for cannabis is well documented, and although he gave up smoking late last year, his weed brand Willie’s Reserve, launched in 2015, is currently in, well, high demand. But he’d also point out that his buddies Waylon Jennings, Merle Haggard, Billy Joe Shaver, David Allan Coe, and so many more were just as integral to the building of the mystique. The thing they have in common: They grabbed life by the throat and never let go.

Nelson picks up that thread and runs with it. “You know, Buddy and I also wrote some stuff for a new album that we’ve started,” he reveals. “One song is called ‘Live Every Day’—that’s the title. It goes, ‘Treat everyone like you want to be treated, and see how that changes your life. Yesterday’s dead, tomorrow is blind, and the future is way out of sight. So just live every day like it was your last one, and one day you’ll be right.’” He pauses again, to let the words sink in.

“It’s not bad,” he says finally.

Not bad, indeed. Read on for the rest of Premier Guitar’s candid chat with the one and only Willie Nelson.

Willie Nelson with his soulmate, Trigger, a 1969 Martin N-20 with a Prismatone pickup, at a Farm Aid concert in Bristow, Virginia, in 2016. Nelson acquired Trigger new in 1969 and has played it almost exclusively ever since. Photo by Matt Condon

How do you and Buddy Cannon write songs together when so often you’re in different places?

Willie Nelson: Well, a lot of the time we text back and forth, or on email. I’ll get an idea for a song and write a verse to it, and send it to him, and he might like it and write another verse. Then we’ll come up with a melody—he will or I will—and the next thing you know we’ve got a song.

You have some talented musicians on this album, and a couple of great guitarists in the mix, with Mike Johnson and Bobby Terry. There’s a real chemistry to how you sound together that isn’t just Buddy’s studio magic.

Yeah, that’s the way it should work. Buddy has access to all those great musicians—pop, country, jazz, whatever—and he works with the musicians that he feels can get the job done. He knows them all, and he’s got a great phone book. But I agree, the guitar players on these albums are incredible, and that’s before I put Trigger on there, so I hope I didn’t screw it up! These guys are just fantastic, and I wouldn’t want to take a note away from them.

There are some great videos online of Mark Erlewine working on Trigger. Watching him make his repairs, it really brings home how much that guitar has been loved. You’ve probably been asked a million times about what this guitar means to you, but how do you and Buddy actually record Trigger in the studio?

Well, that’s all up to Buddy and the engineers. I just bring it to the studio and try to tune it up, play what I’m thinking and let them handle it from there. And you know, with Trigger, I really fell in love with that guitar because it reminded me a lot of Django Reinhardt and the sound that he got on his [Selmer] guitar. That’s the sound that I really like, and Trigger just came out sounding normally a lot like that, and it’s a Martin. I bought it in Nashville, sight unseen, you know? I just told Shot Jackson up there [at the Sho-Bud guitar shop] to send me a Martin guitar, and that’s what they sent me. Just lucked out all the way.

When you get Trigger back from Mark, do you find yourself having to adjust to the guitar again?

No, I just expect it to be there [laughs]. Tom Hawkins is my guitar guy on the road. He takes care of the guitar and makes sure it’s there and hooked up and ready to go on every show. When it needs something, he takes it to Mark and they work on it.

Guitars

1969 Martin N-20 named Trigger (modified with a Prismatone pickup)

Amps

Mid-’60s Baldwin C1 Custom

Effects

None

Strings and Picks

LaBella 830 Folksinger strings (golden alloy and black nylon)

I hear Django in your solos, but also something distinctly south-of-the-border, especially in “First Rose of Spring.” Going back to an album like Spirit, Mexican and Spanish styles really come through in your playing. What has that influence meant to you over the years?

Oh, I’ve always laughed and told stories about that. My mother was a great gal, a great character really. She came from Oklahoma, and had a lot of Indian blood, but the closer she got to Texas, the more she told people that she was Mexican. So I don’t know whether I’m Mexican or Indian, but I don’t care, you know? [Laughs.] But yeah, I grew up listening to the music, and Bob Wills [and the Texas Playboys] was one of my favorite bands to listen to. He had some of the greatest musicians in the world, ever, and I was lucky enough to learn from some of those guys.

You’ve mentioned Jimmie Rodgers, Scotty Moore, and James Burton as some of your favorite guitar players.

[Hank] “Sugarfoot” Garland—you ever hear of him?

Can’t say I’m familiar.

Check him out. He had a big hit song called “Sugarfoot Rag.” Grady Martin [Willie’s lead guitarist on tour in the ’80s] was one of my favorite guitar players. But then, you know, you run out of names pretty quick when you start looking back. I think I’ve learned something from every guitar player that I ever listened to. Ernest Tubb had another guitar player [Billy Byrd]; his style was really simple, but I learned as much about it as I could. Django, Grady, all those guitar players had something that I could learn because I was coming from nowhere, you know?

Do you feel that over all these years you’ve gotten better as a guitar player?

[Laughs.] I hope so.

I don’t mean that to be a loaded question.

[Laughs.] No, I know what you’re saying. Yeah, I think I’ve gotten better.

Your playing on “We Are the Cowboys” brings that across. You’ve known Billy Joe Shaver for a long time, and I’ve always loved the version you did with Kris [Kristofferson] and Waylon [Jennings] because it’s so loose and heartfelt. This version is tighter, but just as bluesy. What drew you to record it again?

Oh, I don’t know. It just seemed to fit the album, and I wanted to do a Billy Joe song. He and I are big buddies and good friends. I think he’s one of the greatest writers out there. We don’t see each other that often, but we text back and forth, and I check on him, see how he’s doing. Him and David Allan Coe and all those guys are friends of mine, and I keep in touch with them as best as I can. I was gonna try to get Billy Joe into the studio with me when I did “We Are the Cowboys,” but I think he might’ve had a health issue or something, so he couldn’t come.

Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings, shown here onstage together in 1991, were lifelong friends who pioneered the outlaw country subgenre and formed the Highwaymen supergroup in 1985 with Johnny Cash and Kris Kristofferson. Photo by Ken Settle

Then there’s “Just Bummin’ Around”—a lyric in that one seems tailor-made for you: “I got a million friends / I don’t feel any older / I got nothing to lose, not even the blues.”

That’s a fun song to play, but I was reluctant to put that song in there. I knew it was a good one and I’ve sung it for years. I just wasn’t sure it fit the album. I wasn’t sure that it didn’t break up the mood too much. And then the more I thought about it, I said well maybe we do need to break up the fuckin’ mood a little bit [laughs].

Were you worried the mood was maybe a bit too dour?

Well, I don’t know. I didn’t think that, but Buddy really liked that song, so I said, you know, let’s put it in there. Why not?

I’ve read that this is your 70th album. That’s an incredible feat.

[Laughs.] Yeah. I think I was gonna be really lucky if I ever got one made.

What’s next for you? You’ve talked about another Sinatra album [to follow up 2018’s My Way] and a recording with Ringo Starr.

Well, the Ringo thing is a charity deal. It’s just a one-time thing that I did. But the Sinatra album, it’s not finished yet. I want to redo the vocals on it, I think, before it comes out, because it’ll be a while anyway. So I just want to live with it a while and let Buddy think about it, and see what we want to do with it.

And my sister [Bobbie]—she’s great. Right now we’re thinking about another gospel album. I’m just waiting on things to get a little easier out there to move around, before I get back into the studio with her and the band. But you know, we still haven’t got First Rose of Spring out, so it’s too early to start thinking about another album. We’ll get there.

Sometimes Trigger needs a rest, too. In this recent clip of Willie Nelson and his sons Micah and Lukas playing “Hands on the Wheel” for Farm Aid 2020, Willie plays one of many other Martin acoustics he’s owned over the years. In 1998, Martin introduced the limited edition N-20WN Willie Nelson signature model—now a very desirable rarity.

Austin-based luthier Mark Erlewine gives a closeup look at Willie Nelson’s famous Trigger acoustic and explains how he keeps the workhorse guitar in shape.

From left to right: Big Kenny Alphin, Hank Cochran, Willie Nelson, and Buddy Cannon at Sound Kitchen Studios in Franklin, Tennessee, during the sessions for Nelson’s 2008 album, Moment of Forever. Photo courtesy of Shannon Finnegan

Trigger Happy: Buddy Cannon on Recording with Willie

Buddy Cannon uses two rules of thumb when recording Willie Nelson and Trigger in the studio: keep it simple and capture everything.“Things can move pretty fast with Willie,” Cannon says. “One time we did 10 or 12 songs in three hours. I mean, that’s cutting tracks and everything. We didn’t even know we were going that fast. And every pass is just full of magical things that nobody else is ever gonna play like that. His guitar licks are like one-time events—they’re just for Willie. They’re not for anybody else to play. So I try to make sure that I don’t miss any of those super-magical things.”

On First Rose of Spring, most of Nelson’s vocal and guitar takes were tracked at his Pedernales Studio in Texas, with Steve Chadie engineering, while a few sessions took place at Blackbird Studio in Nashville with Cannon’s trusted engineer Tony Castle. After many years working together, they’ve perfected a stripped-down approach to recording Nelson’s performances that started with Cannon’s desire to recreate the sound of classic albums like Yesterday’s Wine and Red Headed Stranger.

“These guys all understand what I’m doing, and what I try to do is to make all these albums sound like Willie was sounding in his heyday,” Cannon explains. “I mean, I fell in love with Willie’s music back in the ’60s when I first heard him, and his records were not cookie-cutter even back then. I don’t want to change the things I love about him. It’s just kind of an issue of trust, I think. It just works out.”

When Nelson records a vocal take, he usually plays along on Trigger, so Cannon has to be set up to document every nuance. “The guitar bleeds into his vocal mic, but he may play and sing on one pass, and then do another pass right behind it where he won’t play. He just plays whenever he feels like it, and you’ve got to be ready to capture what he does, or what he doesn’t do. He also plays through the Baldwin amp. We set that behind him and put a mic in front of it. So we have the amp miked, and then we have the guitar coming in through the vocal mic. It’s usually a blend of those two, with the amp being the primary guitar sound.”

With so much to work with, and with all of it coming in a flurry of activity, Cannon and Nelson don’t have time for in-studio playbacks, or for thinking about whether a particular take was a keeper. “I usually go through all the guitar passes, and sometimes I’ll comp one together,” he says. “But I try to keep it simple. If I do comp one together, I try to make it sound like it was played live. And when we get the last mix done and hand it off to the record company, it’s time to start working on the next one. That’s pretty much the way it goes.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)