One of the things I’ve always been really

fascinated by is the idea of “finding

your own voice.” What does that mean?

Where do you find it? Most importantly,

when have we reached a level where it’s

appropriate to begin the search?

When I was a teenager, having been playing for about six years or so, I started to notice that it seemed like some players were born with a natural talent for being unique. They were composing and improvising innovative music all the time, while the majority of us had to stay focused on learning the fundamentals before we could even begin to contemplate something different. On the flip side, though, I’ll never forget the feeling of picking up the guitar when I was five and having the sense that the instrument contained infinite potential, as though it was overflowing with unique and interesting applications. I started to wonder if maybe having a unique and individual sound was really reserved for the elite few, or perhaps there was something I could be doing to encourage a more creative and fresh musical approach like I felt at the very beginning.

This pursuit led me to explore one of the most profound areas of creative expression—how we practice. Over the past few years, I’ve become increasingly interested in how our musical development unfolds when we’re driven by sincere curiosity, rather than a regimented routine that’s always rooted in achievement.

As jazz guitarists, there are certain prerequisites we have to master in order to begin developing our personal relationship to the music. We need to understand the physical mechanics of how to play the guitar, gain an intimate knowledge of the fretboard, and acquire a firm understanding of scales, harmony, rhythm, and improvisation. The unifying factor that can encompass all of these elements is the act of playing a song. As in so many genres, songs act as the platform on which musicians connect. It’s the musical environment in which we get to realize our relationships with one another, with our instruments, and with our underlying creative impulse.

In learning a song, you are given an opportunity. You can choose to focus on learning the melody, the chords, or both together—perhaps in a particular orchestration like a chord-melody arrangement. Each of these approaches will grant you access to the musical world that lives within the composition. If you learn a song by committing one specific arrangement to memory, however, you often end up defining your role in the relationship as one thing, which down the road can cause you to feel trapped, or unable to expand upon your relationship to the song as your playing and knowledge of music increasingly develops. In essence, it’s perhaps most liberating to learn songs the way a classical conductor might learn a symphony. If you study the complete picture of a tune, you will be free to experience the beauty of all its dimensions.

One of my favorite ways to go about this is by using a technique I learned from one of my greatest guitar heroes and teachers, Tuck Andress. To paraphrase, Tuck talked about breaking a song up into its three primary dimensions: melody, bass, and harmony. In most jazz standards, the melody and bass act as a kind of framework that stays constant no matter how the piece is interpreted. However, the harmonic content—meaning the voicings you choose—are subject to change, and will vary from player to player.

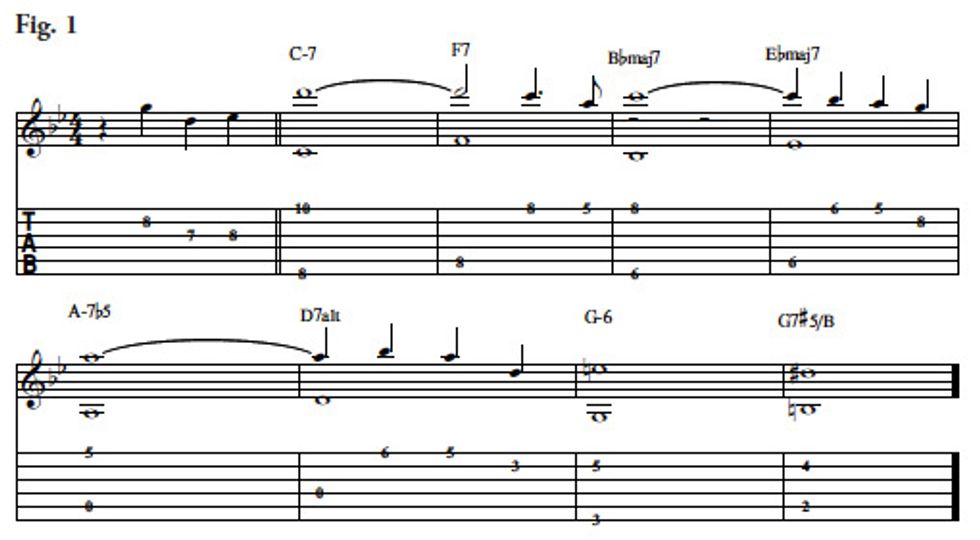

So given that jazz players are encouraged to improvise within the structure of the song, Tuck talked about learning how to play the bass and melody of the song simultaneously before we include the harmonies. This way, we establish a kind of general architecture for the piece, allowing us to fill in the chords as we wish. You can see in Fig. 1 what this basic architecture looks like.

or download example audio

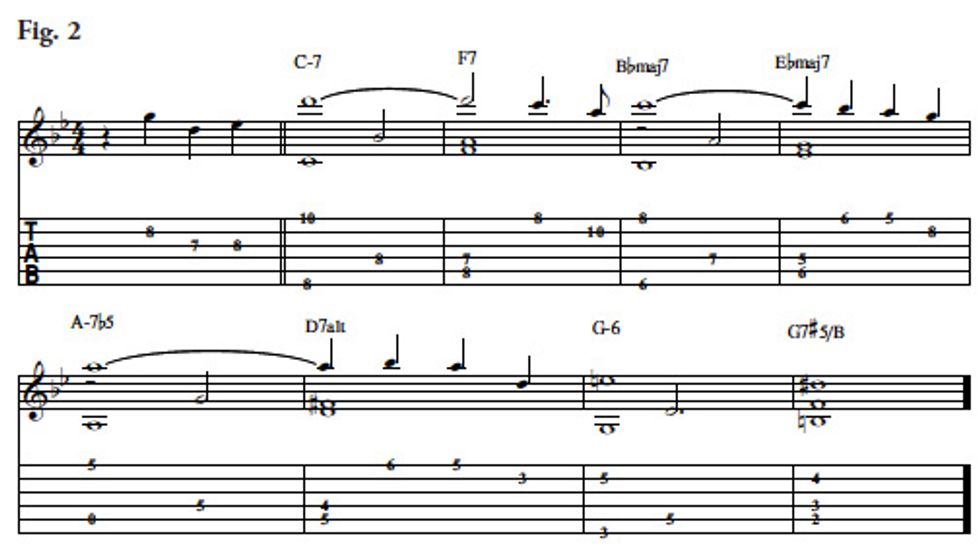

Once you feel comfortable with outlining each measure with the melody and bass, it’s time to add a third part. The purpose of this step is to begin adding color to the basic structure. The key here is to start small and to think in terms of melodic phrases, more than stacking chord tones on top of each other to create voicings. If you are playing a Cm7, you may want to play something that highlights the b3 or b7 of the chord. Conversely, you may chose to keep the tonality more ambiguous by playing lines that center around the chord’s 5, 9, or 11. This line acts as a counterpoint to the bass and melody.

In Fig. 2, I embellish the original version with some basic harmony. It happens to imply harmonic motion, but should also form a melodic figure in and of itself. If you want to explore the art of inner voicings even deeper, I encourage you to check out J. S. Bach’s four-part chorales.

or download example audio

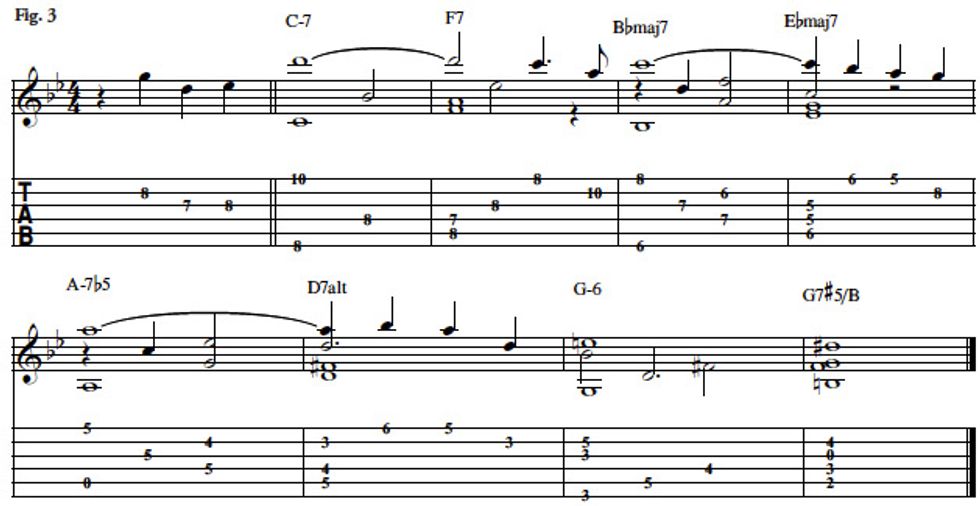

Lastly, start playing with what happens when you add another voice to the mix as seen in Fig. 3. Does it enhance the harmony? Does it take away? Does it paint a harmonic picture strong enough that if the bass were to drop out, you would still hear the voice leading? How does this inform your sense of soloing over the changes? Does the line between improvising and playing the song start to blur?

or download example audio

What I find so beautiful about this approach to learning a new song is that you become acclimated to its melody and overall structure in relation to an ever-changing set of harmonic circumstances. And what makes this approach even more special is how you can accidentally discover voicings that might not otherwise have been obvious choices. In essence, during these formative stages, we’re allowing ourselves to make friends with the music, rather than taking ownership or falling prey to it. From that perspective, anything is possible.

Julian Lage

Julian Lage

Julian Lage is one of those rare musicians who feels equally at home in acoustic and jazz circles. He has been a member of legendary vibraphonist Gary Burton’s group since 2004, and also regularly collaborates with pianist Taylor Eigsti. Lage’s latest album, Gladwell, reflects his wide-ranging musical interests and talents by incorporating chamber music, American folk and bluegrass, Latin and world music, traditional string-band sounds, and modern jazz. For more information, visit julianlage.com.

When I was a teenager, having been playing for about six years or so, I started to notice that it seemed like some players were born with a natural talent for being unique. They were composing and improvising innovative music all the time, while the majority of us had to stay focused on learning the fundamentals before we could even begin to contemplate something different. On the flip side, though, I’ll never forget the feeling of picking up the guitar when I was five and having the sense that the instrument contained infinite potential, as though it was overflowing with unique and interesting applications. I started to wonder if maybe having a unique and individual sound was really reserved for the elite few, or perhaps there was something I could be doing to encourage a more creative and fresh musical approach like I felt at the very beginning.

This pursuit led me to explore one of the most profound areas of creative expression—how we practice. Over the past few years, I’ve become increasingly interested in how our musical development unfolds when we’re driven by sincere curiosity, rather than a regimented routine that’s always rooted in achievement.

As jazz guitarists, there are certain prerequisites we have to master in order to begin developing our personal relationship to the music. We need to understand the physical mechanics of how to play the guitar, gain an intimate knowledge of the fretboard, and acquire a firm understanding of scales, harmony, rhythm, and improvisation. The unifying factor that can encompass all of these elements is the act of playing a song. As in so many genres, songs act as the platform on which musicians connect. It’s the musical environment in which we get to realize our relationships with one another, with our instruments, and with our underlying creative impulse.

In learning a song, you are given an opportunity. You can choose to focus on learning the melody, the chords, or both together—perhaps in a particular orchestration like a chord-melody arrangement. Each of these approaches will grant you access to the musical world that lives within the composition. If you learn a song by committing one specific arrangement to memory, however, you often end up defining your role in the relationship as one thing, which down the road can cause you to feel trapped, or unable to expand upon your relationship to the song as your playing and knowledge of music increasingly develops. In essence, it’s perhaps most liberating to learn songs the way a classical conductor might learn a symphony. If you study the complete picture of a tune, you will be free to experience the beauty of all its dimensions.

One of my favorite ways to go about this is by using a technique I learned from one of my greatest guitar heroes and teachers, Tuck Andress. To paraphrase, Tuck talked about breaking a song up into its three primary dimensions: melody, bass, and harmony. In most jazz standards, the melody and bass act as a kind of framework that stays constant no matter how the piece is interpreted. However, the harmonic content—meaning the voicings you choose—are subject to change, and will vary from player to player.

So given that jazz players are encouraged to improvise within the structure of the song, Tuck talked about learning how to play the bass and melody of the song simultaneously before we include the harmonies. This way, we establish a kind of general architecture for the piece, allowing us to fill in the chords as we wish. You can see in Fig. 1 what this basic architecture looks like.

or download example audio

Once you feel comfortable with outlining each measure with the melody and bass, it’s time to add a third part. The purpose of this step is to begin adding color to the basic structure. The key here is to start small and to think in terms of melodic phrases, more than stacking chord tones on top of each other to create voicings. If you are playing a Cm7, you may want to play something that highlights the b3 or b7 of the chord. Conversely, you may chose to keep the tonality more ambiguous by playing lines that center around the chord’s 5, 9, or 11. This line acts as a counterpoint to the bass and melody.

In Fig. 2, I embellish the original version with some basic harmony. It happens to imply harmonic motion, but should also form a melodic figure in and of itself. If you want to explore the art of inner voicings even deeper, I encourage you to check out J. S. Bach’s four-part chorales.

or download example audio

Lastly, start playing with what happens when you add another voice to the mix as seen in Fig. 3. Does it enhance the harmony? Does it take away? Does it paint a harmonic picture strong enough that if the bass were to drop out, you would still hear the voice leading? How does this inform your sense of soloing over the changes? Does the line between improvising and playing the song start to blur?

or download example audio

What I find so beautiful about this approach to learning a new song is that you become acclimated to its melody and overall structure in relation to an ever-changing set of harmonic circumstances. And what makes this approach even more special is how you can accidentally discover voicings that might not otherwise have been obvious choices. In essence, during these formative stages, we’re allowing ourselves to make friends with the music, rather than taking ownership or falling prey to it. From that perspective, anything is possible.

Julian Lage

Julian LageJulian Lage is one of those rare musicians who feels equally at home in acoustic and jazz circles. He has been a member of legendary vibraphonist Gary Burton’s group since 2004, and also regularly collaborates with pianist Taylor Eigsti. Lage’s latest album, Gladwell, reflects his wide-ranging musical interests and talents by incorporating chamber music, American folk and bluegrass, Latin and world music, traditional string-band sounds, and modern jazz. For more information, visit julianlage.com.