If you had the chance to ask questions about recording the Beatles, what would you want to know? In part two of our interview with producer/engineer Ken Scott, Premier Guitar turned the floor over to

Beatles-hungry musicians with a desire for details. Mr. Scott was gracious enough to respond to their queries.

How much did the room sound of Studio 2 have to do with the ambience of the White Album?

Any room has a certain amount to do with what goes on. “Yer Blues,” as we discussed [in part 1], was recorded in the small room. “Piggies” was recorded in Studio 1, which was huge. “Martha My Dear” and “Dear Prudence” were recorded at Trident, which had a totally different sound, so it’s hard to say what affect the room sound of Studio 2 had, because the album is so varied. If they were playing quieter, there was more pickup of Ringo. If they were loud, you wouldn’t hear as much of the room.

Was there anything different about the way it was set up acoustically—more live or dead?

Every session was set up exactly the same way, at least to start with. At Abbey Road you followed your predecessors, who had determined the best place for everything. On occasion we changed it slightly, but what they spent years finding out was normally the best.

Did they generally record with the floor uncovered or with rugs?

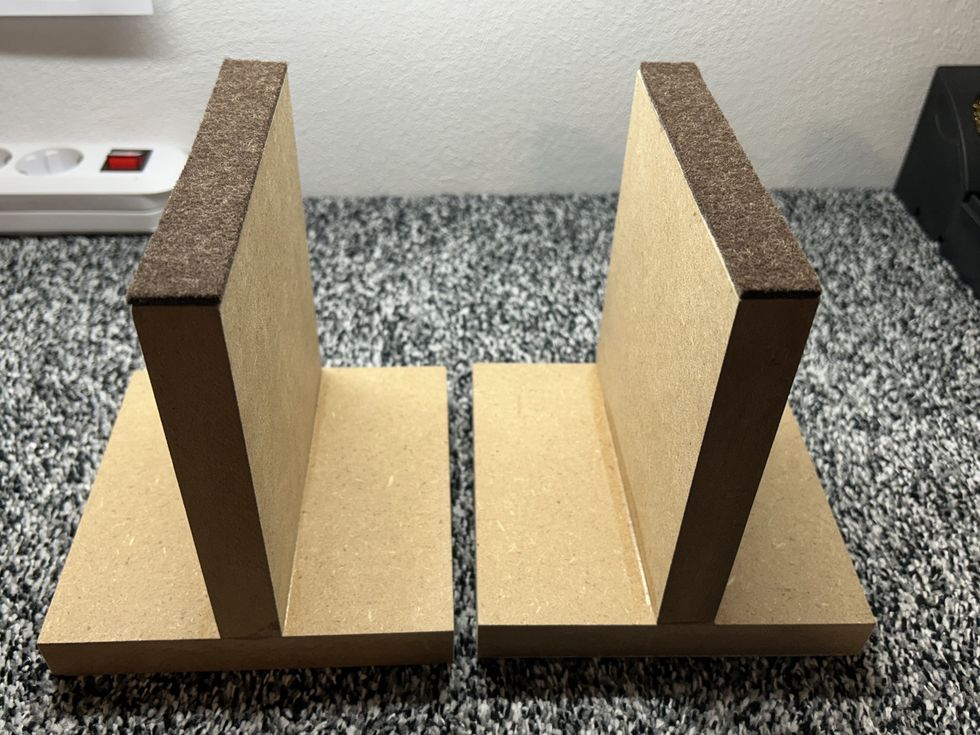

Always with rugs. In Studio 2 it helped with the drums at least not sliding forward too much. With the wood floor there was no way to stick spurs in without ruining it. Generally there weren’t rugs throughout, just under their instruments, so when needed there was enough ambience from the room.

Were there issues using sensitive condenser mics on cranked AC30s, etc.?

No, I certainly never had a problem with the U67s and U87s.

Did each Beatle have a particular intrinsic idea about what they thought both a guitar and amp should sound like? Did they walk into the studio and plug into whatever was there and just play, or did they fiddle around with settings a lot?

They would always walk in, plug in and work through the songs to determine what the songs would be. Then they might change guitars and amps, and we’d EQ it once we knew the direction of the song and what was needed. In the early days, they didn’t have much gear to mess around with, and they didn’t have the time. They were doing sessions from 2:30 to 5:30 and 7 to 10. When they eventually gave up touring, they didn’t have to worry about budgets or time anymore and people gave them plenty of gear.

On the title track to A Hard Day’s Night, is the solo on George’s 12-string Rickenbacker doubled by harpsichord or something?

That was George Harrison on the Rickenbacker and George Martin on piano at half speed. When you play it at normal speed, that’s what you hear.

What can you tell us about “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” from White Album? Any details on the crazy cool guitar solo by Clapton?

Clapton only played on the one track, and with regard to the recording, I have no recollection of him playing! It’s one of the most historical moments in Beatles history and I have no recollection of it at all! I do remember that Eric didn’t want his guitar to sound like a normal Eric Clapton guitar solo, so we used an effect designed by Ken Townsend, which was called either ADT, automatic double tracking, or phasing or flanging. Each is dependent upon how fast you moved this one dial. Chris Thomas remembers sitting and turning the dial fast every time we had to run the track, so that it would make Eric’s guitar sound weird. It’s the original tape flanging used a lot at Abbey Road.

Were there times when you felt that the White Album was a collection of four solo projects under one label?

I guess so, because at the time that overdubs were being done, it was just the songwriter there, controlling everything. The basic tracks were cut as a band. They were together and had a great time. On a couple of occasions, yes, it felt like four solo albums, but overall it was a band project.

What did John use on “Revolution” to create the fuzz tone? Was it a fuzz box or did he blow a speaker?

Neither. They were overdriving two of the mic preamps on an EMI REDD desk that was being used at the time. I was a mastering engineer at the beginning of the White Album recordings, and I happened to go to Studio 3, where they were recording that track. John, Paul and George were all in the control room and had their guitars plugged directly into the board, and Ringo was all on his own on the drums in the studio. Geoff Emerick came up with a very cool way to distort by going in one preamp to overload and into another preamp to distort it even more.

Do you have a favorite Beatles song, and is it one you worked on?

I have several favorites. “We Can Work It Out” is my favorite from Paul. From George, “Something.” From John, “A Day In The Life” and “Strawberry Fields.” From Ringo—not a Beatles song—“It Don’t Come Easy.”

What, if anything, would you have changed on the original recording of All Things Must Pass?

On the original, at the time I would have changed nothing. It was made the way George and I thought it should be made. Thirty years later, in his studio, laughing together, we would have changed it drastically. Neither of us understood why that much reverb was put on anything. We discussed doing it “Un-Spectorized,” taking off the reverb and making it more dry, but the reissue had to be as it was, and all too soon afterward, George got sick and never had a chance to do it.

What is your opinion of Let It Be: Naked?

It was a different way of looking at the album. There’s no right or wrong way to make a record. Some of it I like and some I don’t, and it’s just another look at it. It was OK’d by everyone around and connected with the Beatles, so they must have liked it. There’s good and bad about both versions. I have no problem with something like this as long as the original is still available. I feel the same about mono and stereo versions. So many people never got to hear the music the way the Beatles heard it. We did it all in mono. Stereo back then was Saturday morning with the television on the BBC channel in one corner and the radio on the BBC station in the other corner and you’d spend an hour listening to trains pass by, or a car, or the high spot, a stereo tennis game. Everything was mono until Abbey Road.

Do you prefer the mono mixes on the White Album to the stereo ones?

Probably. I’m still awaiting the mono re-masters from EMI, and I have yet to hear them. From what I remember, yes, because that’s what we spent all the time on. On the White Album they became interested in stereo mixes, because fans would buy both versions and write and tell them of all the differences, so they began making mono and stereo mixes with planned differences.

What do you think of the new remasters?

I have only heard them in stereo and they’re really good, just not as good as the original vinyl. I like vinyl; there’s a warmth to it.

What was it like when John McLaughlin plugged in at the start of a session? Steve Morse? Davey Johnstone?

When we did [Mahavishnu Orchestra’s] Birds Of Fire, John very much had his sound set. He plugged into his Marshall, turned up fairly loud and played. It was very live with very few overdubs. Visions Of The Emerald Beyond took a little more time to get the right tones, but it was still pretty basic.

With Steve Morse it was really different. Very purposefully, I wanted to spend a lot of time not just getting guitar tones per song but for each individual section—a sound for verses, then choruses, if you like, and so on through for solos. I spent a lot of time honing in with Steve, and not much of it was particularly live. I got Rod [Morgenstein] going first, with the others playing DI, and we did overdubs from there. It was very much pieced together accordingly.

With Davey, once again we were recording quickly. There was a certain amount of picking tones for sections, but a lot was done live, so we didn’t change that much. I remember working on one track on his solo album [Smiling Face] with Gus Dudgeon. I can’t remember which track, and a sound wasn’t happening. I finished up with an acoustic guitar, but it was too thin. It had a pickup on it, so I put Davey in the drum booth and fed the guitar through a Leslie. When we mixed the mic’d acoustic with the Leslie sound, it was exactly what was needed. But on Elton John’s albums it was straightforward. We did pre-production at Chateau d’Herouville in France, and from the beginning we were all working on what the songs should be. It was a very collaborative effort. As soon as Elton wrote a song, we’d do pre-production, so I’d say we had a much better idea of the guitar sound for Davey from the get-go.

Would you agree that there is an art to being a sideman?

Absolutely there is an art to it! And it doesn’t lead to being voted number one best guitar player, which says absolutely nothing about your playing.

Is anything more than 16 tracks the "devil's workshop”?

No, it’s not. If 93 tracks are 100 percent needed, that’s fine. What I can’t stand is people not making decisions and ending up with a multitude of tracks that they never use. It makes mixing far more complex. Learning on four-track, from the get-go I had to know what we were heading for, and I had to make decisions, which people don’t do these days, whether it’s four tracks or 192. It’s how we determine the use of them. If the tracks are essential, then it’s no problem. If they’re just jerking off, then basically it does become the devil’s workshop—even if it’s 16 tracks and you only needed eight and the other eight are filled with rubbish.

Here’s an example of what it used to be like, and, believe it or not, it did actually work back then. When George Harrison was recording “What Is Life” with Phil Spector at Abbey Road, they were running out of tracks, so George came to Trident where I was working, and we finished it there. Working with George was always a joy. When he did backing vocals, it was all George. It was tedious, but it was so much fun. We would double it and bounce those down, and double some more and bounce those, getting the mix as we went along. It was a real juggling act to get all the voices on using only an already half-filled 16-track tape, but we had made the decision about what was needed and went for it. Nowadays, every vocal would be on its own track and mixing would be a nightmare.

Interview: Ken Scott, Part 2: Musicians’ Questions About Recording with the Beatles

In part two of our interview with producer/engineer Ken Scott, Premier Guitar turned the floor over to Beatles-hungry musicians with a desire for details.

By Elianne HalbersbergMar 19, 2010