Arnold Schwarzenegger. Crosby, Stills,

Nash, and Young. Yngwie Johann

Malmsteen. Minor seven flat five.

Can you guess what the four names above have in common? I’ll tell you. They all have six syllables. Ar-nold-Schwarz-en-egg-er. 1-2-3-4-5-6. That’s a lot of syllables to have in a single name. I’ve only got three in mine: Paul- Gil-bert. 1-2-3. All those names have double what I have. I’m a bit jealous, but that’s not why I brought this up. I want you to think about this: What does your brain do when confronted with a six-syllable name such as “minor seven flat five?” I know what my brain does. It shuts right off. That’s too many syllables! Especially when I’ve got simpler alternatives to rely on like minor and major (both with just two syllables). This leads me to a story.

A year or so ago, I was giving a lesson to a student. After exchanging a few pleasantries, he said that his regular private teacher wanted to know if I could play any m7b5 arpeggios. It seemed like less of a musical request and more like some kind of guitar-jousting challenge. Something like, “Yeah sure, you can play widdly-widdly with your rock band, but can you play an arpeggio that takes six syllables just to pronounce?”

I managed to squeak out something good enough to defend my reputation. But since then, I’ve delved much deeper into this arpeggio, and I truly love how it sounds. This month, I want to show you how to play it, and why it sounds so good. First of all, I have to comfort you by telling you that it’s an easy arpeggio. Why do I say that it’s easy? Because it only contains four notes. Only four! It has more syllables than notes, for crying out loud. We can breathe easily and safely turn our brains back on.

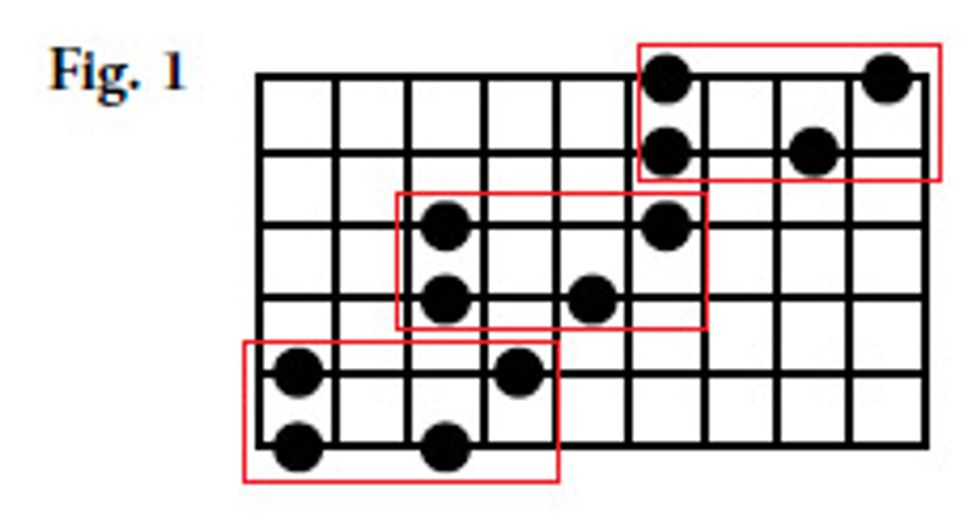

Now I’ll give you the benefit of my research and take you to Fig. 1, which shows the easiest fingering that I’ve found. See, I wasn’t lying. It has just four easy notes. This requires a couple of position shifts, but the shape always stays the same.

I should point out that I’m starting the arpeggio on the b7 (E), not the root (F#). The main reason for this is simply because I really like the shape. I think it’s easy to play, easy to visualize, and still covers all the notes I want. If I rebuild the fingering to start on the root, the shape becomes more difficult and the sound doesn’t improve in any noticeable way. So I’m staying with the easy one!

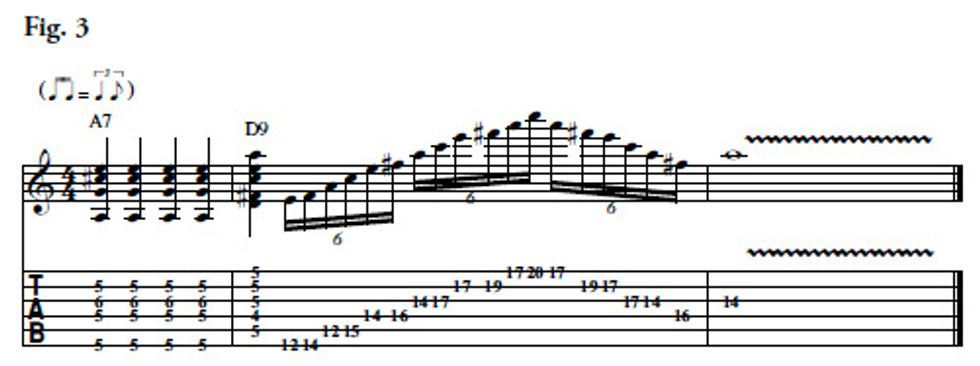

That’s a lot of finger talk. Let’s turn on our ears and listen to the arpeggio in context, by playing it over a chord. Our chord will be a D9, which is a common sound in blues, funk, rock, and jazz. In Fig. 2 and Fig. 3, you can check out the voicing I use along with our arpeggio in context.

I think that’s a nice sound. But you may have noticed something odd. The chord is in D, while the arpeggio is in F#. How does that work? Here is where I should whip out some heady music theory to explain the details of chord substitution, intervals, and extensions. But I’ve made an executive decision to use a metaphor instead, and one that involves Ted Nugent, lots of food, and of course, the IV chord.

Playing a solo over the IV chord is like going to a Thanksgiving party at Ted Nugent’s house. Here’s why: You know that Ted is going to have a turkey. He’ll have proudly plucked it out of the forest with his bow and arrow or possibly even his bare hands. Either way, rest assured that there is a turkey in the oven roasting away. So you, the guest, don’t have to bring any turkey to the party. You might want to bring some cranberry sauce, mashed potatoes, green beans, or strawberry rhubarb pie. But you don’t need to bring any turkey. Uncle Ted has that under control.

After much playing and listening, I’ve discovered that the same is true for the IV chord in a blues progression. The bass, rhythm guitar, piano, or organ will be playing the root (the metaphorical turkey) of the IV chord. So you don’t have to play it in your solo because it’s already there. It sounds more sophisticated to play the musical equivalents of cranberry sauce, mashed potatoes, green beans, and strawberry rhubarb pie, while leaving the turkey to the accompaniment.

The notes in our F#m7b5 arpeggio are the cranberry sauce, mashed potatoes, green beans, and strawberry rhubarb pie. If you look at the four notes in this arpeggio they match up exactly to the notes in our D9 chord, with one exception. There is no D note in our arpeggio. We’re not playing the root in our solo. We didn’t bring the turkey! If you’ve studied music theory, you know this is called a substitution. If you’re a guitar player, you can just think of it as moving a shape a certain number of frets to get a nice new sound.

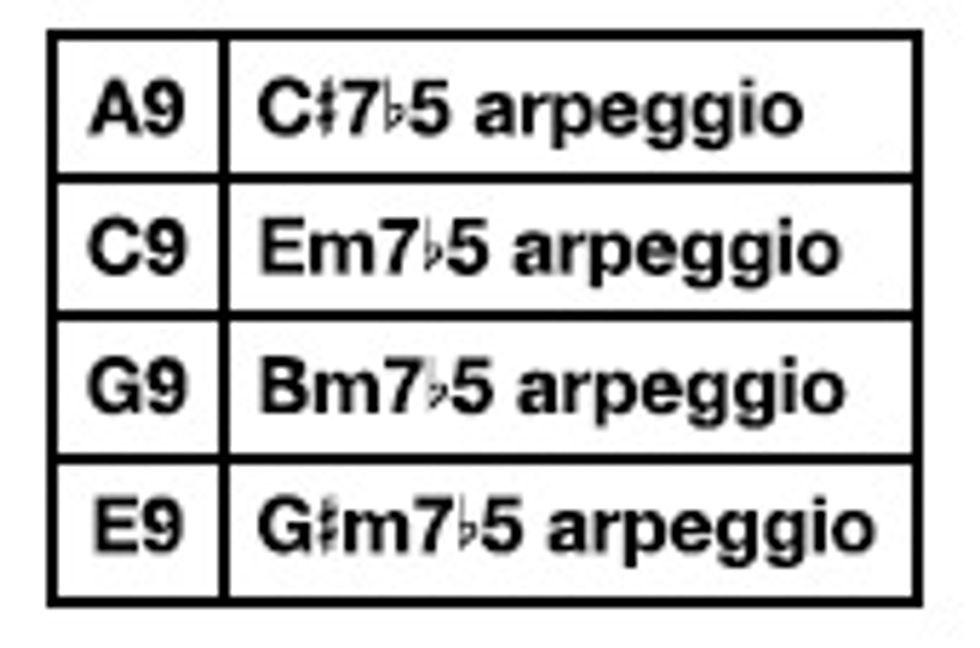

To digest this idea, let’s repeat what we already did, but in some different keys. First play the chord, then play the arpeggio.

There is some math at work here, and I’m tempted to start rattling off some notes and numbers. But I think the best way to “get it” is just to play these examples a few times. I’m going to spare you the explanation and trust that you’ll play these chords and arpeggios for five minutes. Even in that short time, the pattern should become quite obvious, and you’ll no longer need any wordy explanation. Your fingers and ears will already have it. How do you know when you have it? Just try playing dominant 9th chords in some other keys and see if you can figure out where to put the arpeggio. I’m betting that you’ll nail it. I’ll give you five minutes to test it out now.

You’re back. Now let’s do a variation. Since this arpeggio shape is fresh in your mind, I want to show you one more substitution idea. This is where guitar players have a maddening advantage over piano players. On a guitar, it’s quite easy to play a chord and move it up and down chromatically. All you do is lock your hand into the shape and move it up or down a fret. On a piano, chromatic movement requires different shapes. This can be difficult to play and also difficult to visualize. I suggest taking 10 smug seconds to gloat about this. Piano players have so many other advantages, so it’s nice when we can have one too.

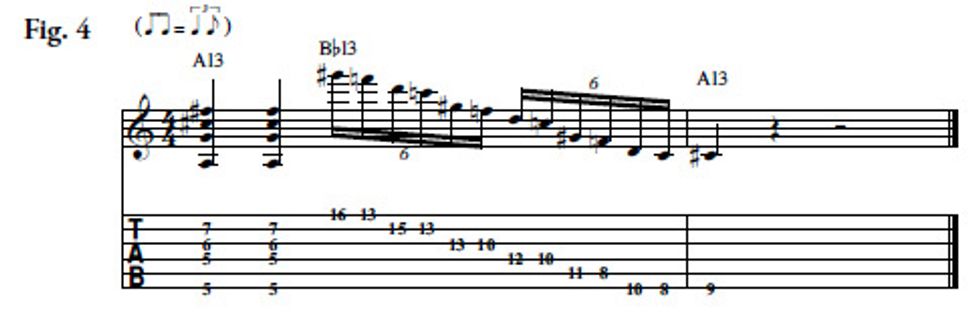

All right. Gloating over. In a blues progression, there are lots of opportunities to do this kind of chromatic movement. It adds a nice tension and release to our old familiar progression. Now let’s use the m7b5 substitution we’ve been playing to outline some of this chromatic movement. In Fig. 4, I want to focus on the Bb13 chord. To outline this chord (without the turkey), I’ll play a Dm7b5 arpeggio. I want to use the same shape that I showed you earlier, but for variety let’s start on the high note this time. Isn’t that cool? I’ve never sounded so sophisticated in my life. All I did was go up a half-step for a moment and leave out the turkey.

I was so excited when I started experimenting with this sound that I decided to search for more fingerings and variations. I’ll quickly show you a couple of my best discoveries.

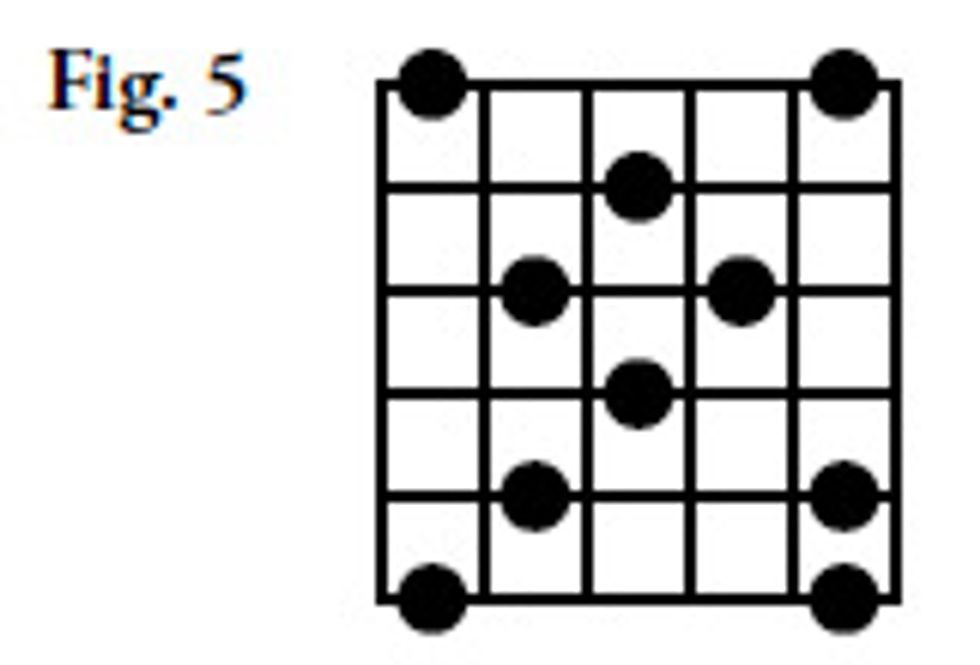

First, I found a more typical fingering for a m7b5 arpeggio. I say it’s “typical” because it stays in one position. For me, the fingering shown in Fig. 5 is not as easy to play at top speed, but it’s in such a convenient location that I still find myself using it a lot. In Fig. 6 I play it over the IV chord and also over our chromatic chord move.

Please make good use of these powerful sounds, and if you missed my column last month [“The Super-Hendrix Scale,” July 2011], I encourage you to go back and have a look. It’s all about soloing over the V chord in a blues, and this will connect very well with the ideas about the IV chord in this column.

And if nothing else, remember that there are only four notes in an F#m7b5 arpeggio. Don’t let that long name clobber you.

Paul Gilbert purposefully began playing guitar

at age 9, formed the guitar-driven bands

Racer X and Mr. Big, and then accidentally

had a No. 1 hit with an acoustic song called

“To Be with You.” Paul began teaching at

GIT at the age of 18, has released countless

albums and guitar instructional DVDs, and

will remembered as “the guy who got the drill

stuck in his hair.” For more information, visit

paulgilbert.com.

Paul Gilbert purposefully began playing guitar

at age 9, formed the guitar-driven bands

Racer X and Mr. Big, and then accidentally

had a No. 1 hit with an acoustic song called

“To Be with You.” Paul began teaching at

GIT at the age of 18, has released countless

albums and guitar instructional DVDs, and

will remembered as “the guy who got the drill

stuck in his hair.” For more information, visit

paulgilbert.com.

Can you guess what the four names above have in common? I’ll tell you. They all have six syllables. Ar-nold-Schwarz-en-egg-er. 1-2-3-4-5-6. That’s a lot of syllables to have in a single name. I’ve only got three in mine: Paul- Gil-bert. 1-2-3. All those names have double what I have. I’m a bit jealous, but that’s not why I brought this up. I want you to think about this: What does your brain do when confronted with a six-syllable name such as “minor seven flat five?” I know what my brain does. It shuts right off. That’s too many syllables! Especially when I’ve got simpler alternatives to rely on like minor and major (both with just two syllables). This leads me to a story.

A year or so ago, I was giving a lesson to a student. After exchanging a few pleasantries, he said that his regular private teacher wanted to know if I could play any m7b5 arpeggios. It seemed like less of a musical request and more like some kind of guitar-jousting challenge. Something like, “Yeah sure, you can play widdly-widdly with your rock band, but can you play an arpeggio that takes six syllables just to pronounce?”

I managed to squeak out something good enough to defend my reputation. But since then, I’ve delved much deeper into this arpeggio, and I truly love how it sounds. This month, I want to show you how to play it, and why it sounds so good. First of all, I have to comfort you by telling you that it’s an easy arpeggio. Why do I say that it’s easy? Because it only contains four notes. Only four! It has more syllables than notes, for crying out loud. We can breathe easily and safely turn our brains back on.

Now I’ll give you the benefit of my research and take you to Fig. 1, which shows the easiest fingering that I’ve found. See, I wasn’t lying. It has just four easy notes. This requires a couple of position shifts, but the shape always stays the same.

I should point out that I’m starting the arpeggio on the b7 (E), not the root (F#). The main reason for this is simply because I really like the shape. I think it’s easy to play, easy to visualize, and still covers all the notes I want. If I rebuild the fingering to start on the root, the shape becomes more difficult and the sound doesn’t improve in any noticeable way. So I’m staying with the easy one!

That’s a lot of finger talk. Let’s turn on our ears and listen to the arpeggio in context, by playing it over a chord. Our chord will be a D9, which is a common sound in blues, funk, rock, and jazz. In Fig. 2 and Fig. 3, you can check out the voicing I use along with our arpeggio in context.

I think that’s a nice sound. But you may have noticed something odd. The chord is in D, while the arpeggio is in F#. How does that work? Here is where I should whip out some heady music theory to explain the details of chord substitution, intervals, and extensions. But I’ve made an executive decision to use a metaphor instead, and one that involves Ted Nugent, lots of food, and of course, the IV chord.

Playing a solo over the IV chord is like going to a Thanksgiving party at Ted Nugent’s house. Here’s why: You know that Ted is going to have a turkey. He’ll have proudly plucked it out of the forest with his bow and arrow or possibly even his bare hands. Either way, rest assured that there is a turkey in the oven roasting away. So you, the guest, don’t have to bring any turkey to the party. You might want to bring some cranberry sauce, mashed potatoes, green beans, or strawberry rhubarb pie. But you don’t need to bring any turkey. Uncle Ted has that under control.

After much playing and listening, I’ve discovered that the same is true for the IV chord in a blues progression. The bass, rhythm guitar, piano, or organ will be playing the root (the metaphorical turkey) of the IV chord. So you don’t have to play it in your solo because it’s already there. It sounds more sophisticated to play the musical equivalents of cranberry sauce, mashed potatoes, green beans, and strawberry rhubarb pie, while leaving the turkey to the accompaniment.

The notes in our F#m7b5 arpeggio are the cranberry sauce, mashed potatoes, green beans, and strawberry rhubarb pie. If you look at the four notes in this arpeggio they match up exactly to the notes in our D9 chord, with one exception. There is no D note in our arpeggio. We’re not playing the root in our solo. We didn’t bring the turkey! If you’ve studied music theory, you know this is called a substitution. If you’re a guitar player, you can just think of it as moving a shape a certain number of frets to get a nice new sound.

To digest this idea, let’s repeat what we already did, but in some different keys. First play the chord, then play the arpeggio.

There is some math at work here, and I’m tempted to start rattling off some notes and numbers. But I think the best way to “get it” is just to play these examples a few times. I’m going to spare you the explanation and trust that you’ll play these chords and arpeggios for five minutes. Even in that short time, the pattern should become quite obvious, and you’ll no longer need any wordy explanation. Your fingers and ears will already have it. How do you know when you have it? Just try playing dominant 9th chords in some other keys and see if you can figure out where to put the arpeggio. I’m betting that you’ll nail it. I’ll give you five minutes to test it out now.

You’re back. Now let’s do a variation. Since this arpeggio shape is fresh in your mind, I want to show you one more substitution idea. This is where guitar players have a maddening advantage over piano players. On a guitar, it’s quite easy to play a chord and move it up and down chromatically. All you do is lock your hand into the shape and move it up or down a fret. On a piano, chromatic movement requires different shapes. This can be difficult to play and also difficult to visualize. I suggest taking 10 smug seconds to gloat about this. Piano players have so many other advantages, so it’s nice when we can have one too.

All right. Gloating over. In a blues progression, there are lots of opportunities to do this kind of chromatic movement. It adds a nice tension and release to our old familiar progression. Now let’s use the m7b5 substitution we’ve been playing to outline some of this chromatic movement. In Fig. 4, I want to focus on the Bb13 chord. To outline this chord (without the turkey), I’ll play a Dm7b5 arpeggio. I want to use the same shape that I showed you earlier, but for variety let’s start on the high note this time. Isn’t that cool? I’ve never sounded so sophisticated in my life. All I did was go up a half-step for a moment and leave out the turkey.

I was so excited when I started experimenting with this sound that I decided to search for more fingerings and variations. I’ll quickly show you a couple of my best discoveries.

First, I found a more typical fingering for a m7b5 arpeggio. I say it’s “typical” because it stays in one position. For me, the fingering shown in Fig. 5 is not as easy to play at top speed, but it’s in such a convenient location that I still find myself using it a lot. In Fig. 6 I play it over the IV chord and also over our chromatic chord move.

Please make good use of these powerful sounds, and if you missed my column last month [“The Super-Hendrix Scale,” July 2011], I encourage you to go back and have a look. It’s all about soloing over the V chord in a blues, and this will connect very well with the ideas about the IV chord in this column.

And if nothing else, remember that there are only four notes in an F#m7b5 arpeggio. Don’t let that long name clobber you.

Paul Gilbert purposefully began playing guitar

at age 9, formed the guitar-driven bands

Racer X and Mr. Big, and then accidentally

had a No. 1 hit with an acoustic song called

“To Be with You.” Paul began teaching at

GIT at the age of 18, has released countless

albums and guitar instructional DVDs, and

will remembered as “the guy who got the drill

stuck in his hair.” For more information, visit

paulgilbert.com.

Paul Gilbert purposefully began playing guitar

at age 9, formed the guitar-driven bands

Racer X and Mr. Big, and then accidentally

had a No. 1 hit with an acoustic song called

“To Be with You.” Paul began teaching at

GIT at the age of 18, has released countless

albums and guitar instructional DVDs, and

will remembered as “the guy who got the drill

stuck in his hair.” For more information, visit

paulgilbert.com.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)