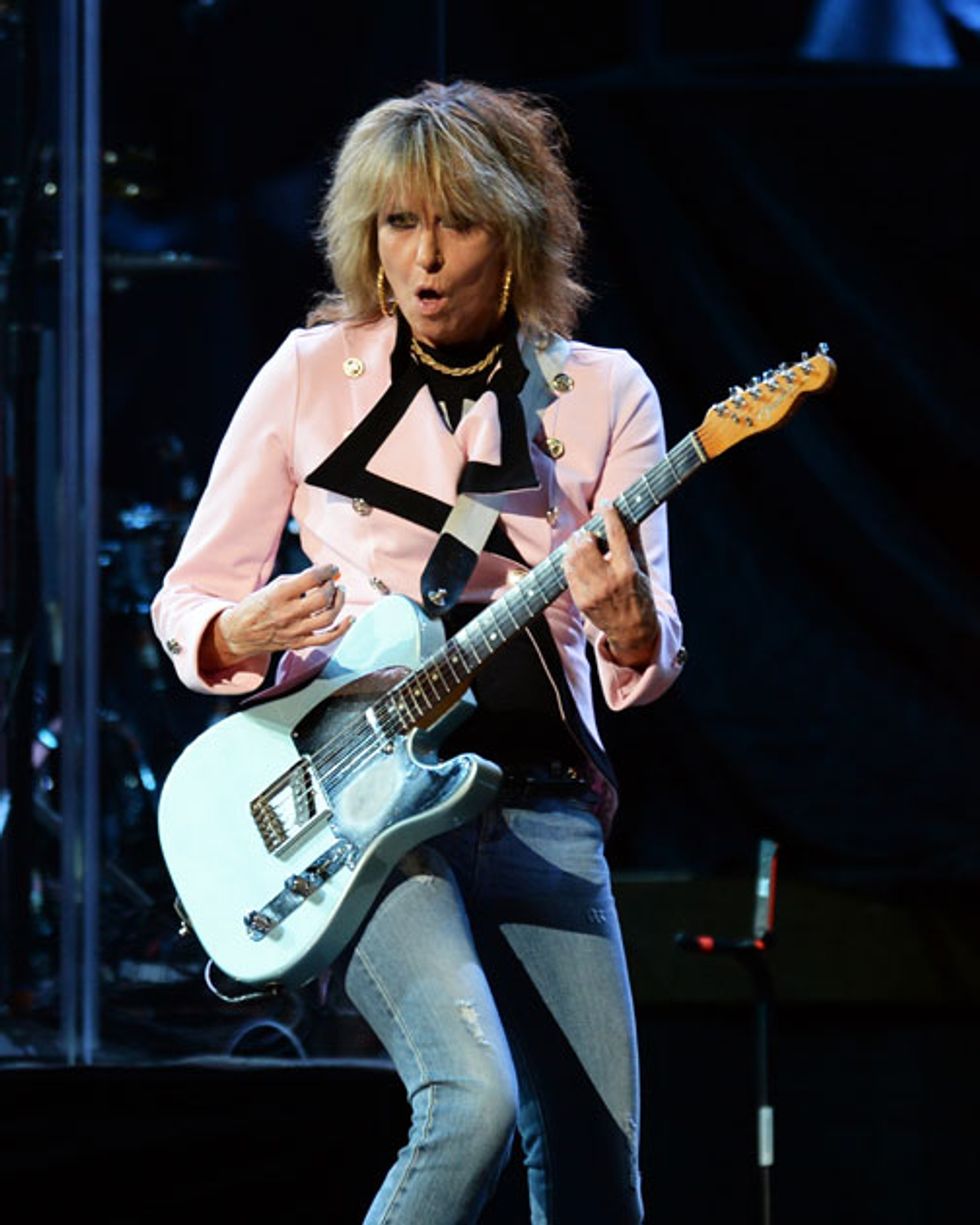

“There’s not a day that goes by when I don’t think, ‘This is fucking great,’” Chrissie Hynde replies when asked about her 36-year run with the Pretenders. She’s right, of course. Growing up in Akron, Ohio—the Rubber City, where she attended Firestone High School—Hynde wanted nothing more than to be in a rock band. And for more than half her life she’s led one of the best through a dozen incarnations—all of them dependent on her poetic writing, her smoky and commanding voice, and her partnerships with a variety of fellow guitarists that have created a perfect union of artful rhythm playing and terse, conflagrant solos, leads, and licks.

Those fretboard collaborations have bristled and purred through truly extraordinary songs. They range from the punk-inflamed and bellicose early classics “The Wait” and “Tattooed Love Boys” to meat-and-potatoes rockers like the title track of the band’s new album Alone to elegant and reflective ballads like “Hymn to Her” from 1986’s Get Close and “Almost Perfect” from 2008’s Break Up the Concrete.

“I’m not really very guitar savvy,” Hynde says. “I just do the job. But I won’t talk to fashion magazines or Esquire or Rolling Stone—all the ones I think have gone the wrong way. So I’m delighted to talk to a guitar magazine.”

She’s also clearly delighted to play guitar, and while Hynde isn’t likely to engage in a deep conversation about orange drop capacitors or tuning machine gear ratios, she is an impassioned and skilled musician who sometimes talks about the guitars she’s owned over the years as if they were pets.

“I didn’t learn to play rhythm guitar by default because I couldn’t play lead,” Hynde explains. “I never tried to play lead. I was a rhythm guitar fan right from being inspired to play by listening to James Brown, where the rhythm was the anchor of the whole song and everything was based around it—sometimes on only one chord. That really turned me on. I like things that never change. I’ve discovered that with the least amount of chord changes you can come up with the most melodies and stuff, and I’ve stayed on that.”

Premier Guitar caught up to the great Pretender in Nashville the morning after Hynde and her band opened for Stevie Nicks in an early November concert at the Bridgestone Arena. Hynde talked about some of her favorite instruments, recording Alone in Music City with Dan Auerbach at his Easy Eye Studio, her band’s current lead guitarist James Walbourne, and what she looks for in a 6-string sparring partner.

I first saw you in 1980 at Toad’s Place in New Haven, Connecticut, on your debut U.S. tour, and you were playing a Telecaster. You’re still playing Telecasters. What interested you in that model and what’s sustained your interest over the decades?

I like the feel and look of it, the necks and everything. But the first electric guitar I had was a Kay—a semi-hollowbody. I was a teenager trying to play [the Butterfield Blues Band’s] “Born in Chicago” and stuff on my own. I didn’t want to jam with anyone, because they were all guys. I missed out on that. I just like to get straight into it—although I really regret that, because that’s where all the fun is and where you can go on a journey with the rest of the band. My excuse is that I was a girl and I never really felt like, you know, wanting to. I would maybe go for it now, but it never comes up. Jams aren’t me.

So I had that Kay electric, and then I had a fantastic little Gibson Melody Maker. I loved that guitar. It was in the boot of a car and got stolen, so a guy I was working with leant me his Melody Maker, and I went into a guitar shop to have the machine heads fixed or changed, and I saw my Melody Maker that had been stolen the past week. They said, “How can you prove it?” I got it for my 21st birthday.

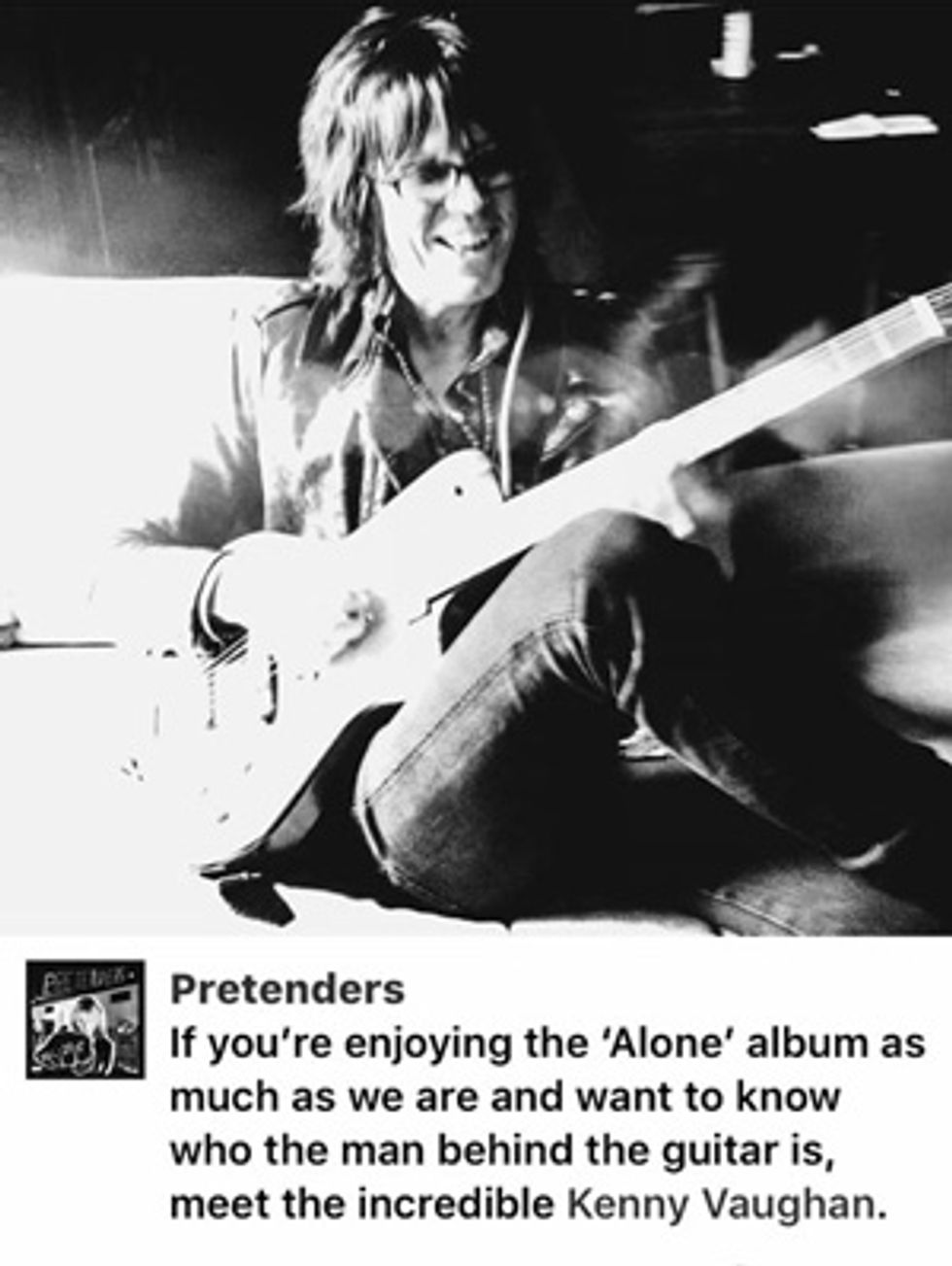

Chrissie Hynde gave Nashville guitar ace Kenny Vaughan a ringing endorsement on Twitter during the recording process.

Then I had an SG—that was a nice, light nifty little thing. James Walbourne is the other guitar player in my outfit and he’s doing amazing things on an SG. And then I don’t know how I got the Tele. Maybe I thought it looked cool or something. But when I first picked one up I thought, “I’ll never be able to carry this for an hour.”

I have a few. I’ve had a couple made … a Zemaitis … but the one I’m using now, I don’t know what year it is. I got it a long time ago and it was already old. They had two in this shop in New York. Maybe in Manny’s. There was one with the original finish and one with spray paint. They said the one with the original finish was worth more. I said, “Give me the other one.” Only because I hate collectors’ things. I’m anti-collector. I thought, “Give me the shitty one.”

I just do the job with my guitar and I’m not as diligent with it as I wish I was. I also found a $200 Stratocaster not long ago. My office had them to sign to give to some charity, and I picked it up and said, “I love this guitar.” So they gave me one and I played it a while at home, but I’m aware of the fact that no one wants to see me playing a Stratocaster. Not that I’m that image conscious, but when I said I was going to bring in a Strat, I could see a look in my guys’ faces, so I thought, ‘Oh, oh. Maybe that’s not such a good idea.’ ”

What did you play on Alone?

I don’t really play on the album. I play on one song. We recorded the album in two weeks. Dan Auerbach plays on all of it, and Kenny Vaughan. I just kind of brought in some demos. I wasn’t very well for those two weeks and wasn’t sure I’d get through the sessions. I was on cortisone. It was changing seasons and I had a bronchitis kind of thing. From being an ex-smoker, smoking all my life, I couldn’t even talk. And Dan said, “Don’t worry about it. We’ll do all the vocals in the last few days.”I was literally crying when I got back to the hotel after the first day, because I was so sick.

[Bassist] Dave Roe would pick me up and take me back to my hotel every day. We’d play the demos, which I sent to Dan before the sessions, and Dave would write out a chart, pass it out to everyone, we’d do three takes, and move on to the next song. And I might croak out a guide vocal.

I played on “Gotta Wait.” That really is a rhythm-driven song. I might have played on “Chord Lord,” too. But I’m playing all the songs now, because we’re doing them live.

“I never tried to play lead,” says Hynde. “I was a rhythm guitar fan right from being inspired to play

by listening to James Brown.” Photo by Larry Marano

You’ve worked with a series of distinguished guitar players. What are you looking for in a guitar foil?

I want excellence. But it’s not about who’s the best; it’s about who does the right thing. I like a guitar player who can hold down the fort with a nice rhythm part, a nice arpeggio, and then let it rip. James is a wild card, so that’s great. I see my position as a singer as being there to set up the guitar player. I orchestrate the band and keep them on their toes, because if it gets polite or you’re going through the motions—game over. It’s not rock ’n’ roll and it’s not fun anymore. If you’re playing for an extended period you have to be very mindful of that. So I’ll come in at a different place or end songs in different spots, or tell James to keep going or cut a solo. He always has to be ready to switch the plan.

I like bands. I’m not, for the most part, interested in individuals. It’s the band dynamic that turns me on. And there you go. The line-ups have changed, but the spirit of the thing has remained the same.

How did you and Dan come to work together on this album?

We’ve met over the years in passing. I don’t think we ever had a conversation. I’d admired him from afar and seen the Black Keys a couple of times. I didn’t listen to the stuff he was producing. I’d seen him play guitar and that was all I needed to know. You don’t know what’s going to happen until you get into the studio anyway, and I didn’t have a real idea about what I wanted. I never do. You just take the songs in. And Dan is absolutely the producer of the moment.

He’s super organic and really traditional, and if you’re traditional in a rock thing, you’re going to be experimental. He sees an album as a two-sided vinyl LP. That sets a kind of boundary so it doesn’t get lost up its own ass. Look at the difference from when people were working with eight tracks and then went to 48 tracks? Less is more.

not such a good idea.’ ”

Dan brought in his Nashville team, including guitarist Kenny Vaughan and bassist Dave Roe, to play on Alone. How different was that from using your own band?

It had a good vibe, just like with my band. The first thing I noticed about all these guys is that they really just want to play rock ’n’ roll. When I walk into the room, they know they’re safe—they know it’s gonna be a rock thing. That’s the impression I get. Everyone wants to be in a rock band, like they did when they were 16.

How has your guitar playing evolved?

I don’t think it’s evolved at all. I’m in exactly the same spot I was at when I was 22. I’ve played more because I’ve gone on tours. I absolutely fucking love guitar, but I don’t dig it that way.

I mean, I started painting a lot this year. Once I start that, I can do it for four hours and not look at or listen to anything else, and not lose focus. Shit, if I did that with a guitar, I’d be a hotshot player by now. But it’s not my medium. For me, it’s more writing songs and singing.

How do you compose?

It’s the rhythm, a few chords, and the melody.

What amps are you using these days?

Two Ampeg Super Jets. I like small amps. I like the sound of the rehearsal room. If you can recreate the sound of the rehearsal room and keep it relatively contained onstage, then the house guy can crank it and control the sound, and that gives him a lot more to play with. If it’s too loud, it’s a mess onstage. We consistently get compliments on our volume.

Chrissie Hynde’s Gear

Guitars1965 Fender Telecaster

Fender Custom Shop Telecaster

1998 Fender Squier Telecaster

1964 Fender Telecaster

Amps

two Ampeg Super Jet SJ-12T reissues

Effects

Fulltone Fat Boost

Boss CE-2 Chorus

Boss TR-2 Tremolo

Boss TU-2 Tuner

Shure wireless

Strings and Picks

D’Addario EXL120s (.009–.042)

Scotty’s medium nylon

Do you use effects?

I use a chorus pedal and stuff, but my guitar tech switches that on the side, so I don’t need to think about that so much.

How did you decide to make another Pretenders album instead of a solo album, like 2014’s Stockholm?

None of them have been solo albums. They’ve all been Pretenders albums, but with different line-ups. For the last album, I went to Sweden and the guys I work with usually were all doing other things. So I thought, “I’ll call it a solo album.” This album also has a different line-up, but when my manager played it for someone, he said, “Oh, it’s great to hear the Pretenders again.” So my manager, Ian [Grenfell], said, “What do you think about calling it a Pretenders album?” So I wrote Dan to ask him what he thought about it, and he said, “Call it whatever sells the most records.”

Your voice has continued to become richer, warmer, and more controlled. How has your singing grown?

I don’t know what to say about that, really. I just do what I do. I don’t know technically how to talk about singing. I don’t train or warm up or rest my voice. I think singing is psychological. The things that are unique about singers are probably the things they don’t like about their voices. I don’t think there were any comps on this album. I just sang the songs a couple times and Dan took the best take. You can tell on one song that I’m hoarse—“Blue Eyed Sky.” I sound like I’m on death’s door, but I got used to it and said, “Oh fuck it.” And I quit smoking a few years ago, and that’s obviously a huge benefit.

You’re having a great career. What do you think when you look back at what you’ve done?

I’m just glad I got away with it, to be honest. I’m on the road and I’m in a nice hotel and I can order room service. Fuck it. When I’m on tour, I’ve got a tour manager who will carry my bags, and when it’s over, I go home and I live above a shop on my own and I can do some painting. I live a very, very ordinary, almost kind of reclusive life at home. And nobody knows who I am. I’m pretty much the same as when I moved to London in 1973. I just do my thing. It feels great! It’s always felt great to be in a rock band. It’s what I wanted when I was 16. I didn’t think it would happen.

YouTube It

In this guitar-laden performance of “Holy Commotion,” the first single from Alone, the Pretenders are joined by the album’s producer, Dan Auerbach, on the BBC’s Later … with Jools Holland. Auerbach plays a Gibson Trini Lopez model as James Walbourne picks the song’s melody riff on a 1950s parts Fender Stratocaster that was a gift from Chrissie Hynde, who strums one of her workhorse Telecasters. And that’s Eric Heywood laying down extra texture on pedal steel.

Laying into a Telecaster that’s now departed his touring arsenal, James Walbourne slams it down with Chrissie Hynde at Chicago’s Riviera Theatre during the Break Up the Concrete tour. Photo by Tim Bugbee / Tinnitus Photography

James Walbourne: “Run Everything Loud and Rock Out”

The Pretenders have a lineage of distinguished lead guitarists, beginning with the incendiary but self-destructive James Honeyman-Scott and continuing with Billy Bremner (Rockpile, Nick Lowe, Dave Edmunds), Robbie McIntosh (Paul McCartney, Roger Daltrey), Johnny Marr (the Smiths), and Adam Seymour (Katydids). That gives the band’s current string-slasher, James Walbourne, 10 pairs of shoes to fill—but the biggest belong to Honeyman-Scott, who helped define the Pretenders’ savage-to-soothing sound on 1980’s Pretenders and ’81’s Pretenders II.“When I first joined the band, it was great to discover all of Jimmy’s parts,” Walbourne says. “He was a great stylist, really, and to try to make those parts my own a bit, without changing up the character of the songs, was a challenge. But Chrissie made it clear that she wanted me to bring my own thing to the table.”

Walbourne’s own thing is, well, nearly a bit of everything. Before joining the Pretenders he played with Americana roots outfit Son Volt and was a member of the Kinks’ frontman Ray Davies’ solo band, navigating the singer-songwriter’s new works and classic-rock catalog. He met his wife, Kami Thompson, while playing on the sessions for her mother Linda’s 2007 album, Versatile Heart.

James Walbourne’s Gear

Guitars1963 Gibson SG Junior with Maestro Vibrola

1968 Gibson Firebird with Maestro Vibrola

1958 Fender parts Strat

1950 Fender Tele Relic

Gibson Les Paul Classic

Amps

two Fender ’68 silverface Deluxe Reverb reissues

Effects

TC Electronic Flashback X4 Delay

ZVEX Box of Rock overdrive

Crowther Audio Hotcake distortion

MXR Custom Audio Electronics Boost/Overdrive

Dunlop Cry Baby wah

Tone Bender fuzz

Boss CE-2 Chorus

Boss TR-2 Tremolo

Strings and Picks

D’Addario EXL15s (.011–.049)

Dunlop Tortex .73 mm

“I’ve played with him quite a bit, so it’s definitely rubbed off,” Walbourne relates. “Now, being in the Pretenders lets me play rock guitar, and the Rails gives me the opportunity to do everything else I enjoy, so I get to have a lot of scope.

“Chrissie is a great rhythm player,” Walbourne continues, “but it’s kind of funny, because sometimes she gets so lost in performing that she forgets which fret she’s on. But she’s always inspiring. She writes aggressive lyrics that really bring out an aggressive edge in my guitar playing, and I love that she can go from extreme rock to doing a ballad seamlessly. She’s a natural, and she can also write some really complicated rhythms, like in ‘The Phone Call.’ To get your head around a song like that takes some time. The bottom line is, her guitar drives the band—even Martin. Besides that, she’s just amazing to be around. When we’re not onstage we always talk about music and have quite a good time, really.”

It also took Walbourne some time to wrap his head around chorus pedals, which Honeyman-Scott made a staple of the Pretenders’ foundational sound with his ringing chord stabs and arpeggios in numbers like “Mystery Achievement” and the band’s first single, “Brass in Pocket.”

“To me, they were the Devil’s pedal,” Walbourne says. “I couldn’t stand them, really, but Jimmy made it work. He was fantastic with the chorus and used it to really create his own sound, instead of that horrible singer-songwriter chorus approach. So now I can’t be without one.”

Another essential element for Walbourne’s tone is volume. “I run everything loud and just rock out on it,” he says. “I turn everything up on my amps and guitar, and I don’t touch my volume and tone pots except for some swells on ‘Hymn to Her.’ I don’t like to fiddle around. I just like to concentrate on playing.”

Dave Roe plays his Lemur Music Jupiter upright at Easy Eye Studio. He ran the bass through a custom DI, a console sidecar, and a compressor.

Kenny Vaughan and Dave Roe: Inside the Alone Sessions

If you check the credits on Dan Auerbach-produced albums by the Arcs, Nikki Lane, Ray LaMontagne, and Lana Del Ray, you’ll notice the names of guitarist Kenny Vaughan and bassist Dave Roe. They’re regularly drafted for sessions at Auerbach’s Easy Eye Studio because they’re among Nashville’s sharpest and most versatile players, and they likely appeal to Auerbach because of their ability—although it’s practically an insistence—to think outside of the box. Plus, they have tone for eons.

During their regular Monday night gigs together at Nashville’s 12 South Taproom, Roe and Vaughan’s sets rip from surf music to jazz to swamp blues to R&B to classic country to originals to, really, just about anything that crosses their minds. Today Vaughan’s most high-profile gig is with Marty Stuart’s Fabulous Superlatives, where he and Stuart regularly engage in virtuoso crossfires. Early on, Vaughan was a student of Bill Frisell and he left an indelible mark on the music of Lucinda Williams during his tenure in her band. Roe held the bass chair in Johnny Cash’s group for 12 years and has played the same role for Dwight Yoakam and, more recently, John Mellencamp. They’re also in demand throughout the broad spectrum of Nashville’s recording scene.

Vaughan praises Auerbach’s approach: “Dan takes each song as a separate entity, and maintains a focus on the song until he sees it through. He doesn’t fall prey to letting other tunes on the project affect the one he’s sculpting at the moment. There’s none of that foolish, ‘Oh, we can’t do that because we did that on the last song’ mentality, which is something that drives me nuts. He looks for the essence of each song, and that takes work. Sometimes you have to admit that you’ve gone down the wrong road and you need to break it down and start over.

“Recording with Chrissie was great,” Vaughan adds. “She’s easy to work with and very open to trying things out. She’d stand there and sing live with the band, and we’d all get shivers when that voice came through the speakers.”

For each song, Vaughan was “assigned a position: electric guitar, acoustic guitar, sound effect guitar, baritone guitar, etc.—and then we’d look for the right instrument and amplifier to make it happen. I don’t use a pedalboard, but there are hundreds of pedals around if you might need to try one. I don’t recall using one.” A highlight: “I played my Dan Dunham Junior Watson model through a cranked tweed Gibson GA-5 on the rock tune with all the chords [“Chord Lord”] and the solo went down live in one take. It was a roller coaster ride.”

“If anything was out of the ordinary about the sessions,” says Roe, “it was just that it was Chrissie fucking Hynde! Working with Chrissie was unbelievable, on so many levels. From day one, I’ve always been a Pretenders fan, and she’s one of the best singer-songwriters ever. Once I was able to step back from that, it turned into a really enjoyable place to be. She was delightful, extremely intelligent, and a really fun hang. Chrissie totally handed the reins to Dan, trusted him and us, and it went great. To hear that voice in the phones was sublime and inspiring.

“I also loved hearing her stories about the Pretenders starting out in England,” Roe continues. “Most everyone associates them with the British punk and post-punk explosion of the late ’70s, so one of the striking things for all of us was the realization that the Pretenders never related to that at all. They had that punk energy for sure, but it surprised them to find that they were lumped into that. I think that the playing level in that band was far beyond any of that.”

Roe used Auerbach’s vintage Fender Mustang with La Bella flatwound strings that he almost always uses for Easy Eye recordings. “The way that the bass sits in the mix on those old records is what he goes for. He loves to say that you can ‘see the bass,’ and I get that,” Roe relates. “Modern music, especially the stuff that comes out of Nashville, is overloaded with a sort of false low end that really doesn’t allow for much movement. I like that as well, but it’s not right for everything.” Roe also played his Lemur Music Jupiter upright, a 3/4-size bass with a 7/8 body strung with “the classic Nashville upright setup—flats on the bottom, and gut G and D.” He also employed a Collin Dupuis custom DI through a channel of an Altec 9300 console sidecar through a Universal Audio LA-3A compressor. The Jupiter was miked with a Funkwerk Leipzig RFT 7151 through an Old World Audio U33 compressor for color, not to compress.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)