In mid-’60s Europe, if you were hip and dug music, swinging London was the place to be. The Beatles were there, as were the Stones, the Who, the Small Faces, the Kinks, and every other great British band of the day. The British blues boom was flourishing, too—Eric Clapton and Peter Green, the Yardbirds, Alexis Korner, John Mayall. Chas Chandler brought Jimi Hendrix to London to launch his career. Youth, money, fashion, style, music, art—the stars aligned, forces converged, and London was the epicenter of cool.

But London had its outliers, too. Timebox, a small band with a minor hit, was playing the clubs. They were known for their live shows, which were manic, unpredictable, and nothing like their radio-friendly singles. Their guitarist, Ollie Halsall, was emerging as London’s guitarists’ guitarist. He was different. He played faster. His note choices were unusual. His phrasing was unique. He was fearless, reckless, impulsive, hysterical, and listening to him was an adventure. The people who saw those shows still recall them with awe.

Fame eluded Halsall, but his influence was enormous. XTC’s Andy Partridge summed him up in an interview for PopDose in June 2009: “Once I heard [Halsall’s] guitar playing, I was, like, ‘Oh, I need to be able to play like that.’”

Catching the Vibes

Halsall was born on March 14, 1949, in Southport, England, a small city just north of Liverpool. His given name was Peter, but everyone called him “Ollie,” a play on the pronunciation of Halsall (pronounced ’Alsall).

Halsall started playing the guitar at 7, but it wasn’t long before he decided to take up the drums instead. He joined his first band, the Music Students, at 13, but that didn’t last either. Clive Griffiths, a school friend, was living in London, and he invited Halsall to join him. Griffiths wanted Halsall to join his new band, Take 5, but playing vibes, not drums.

Halsall didn’t know how to play vibes, but that didn’t stop him. “I always wanted to be a vibes player,” he told Melody Maker in January 1972. “I used to listen to Milt Jackson all the time. Griff knew that, and he sensed I was a natural musician because I was a pretty good drummer.”

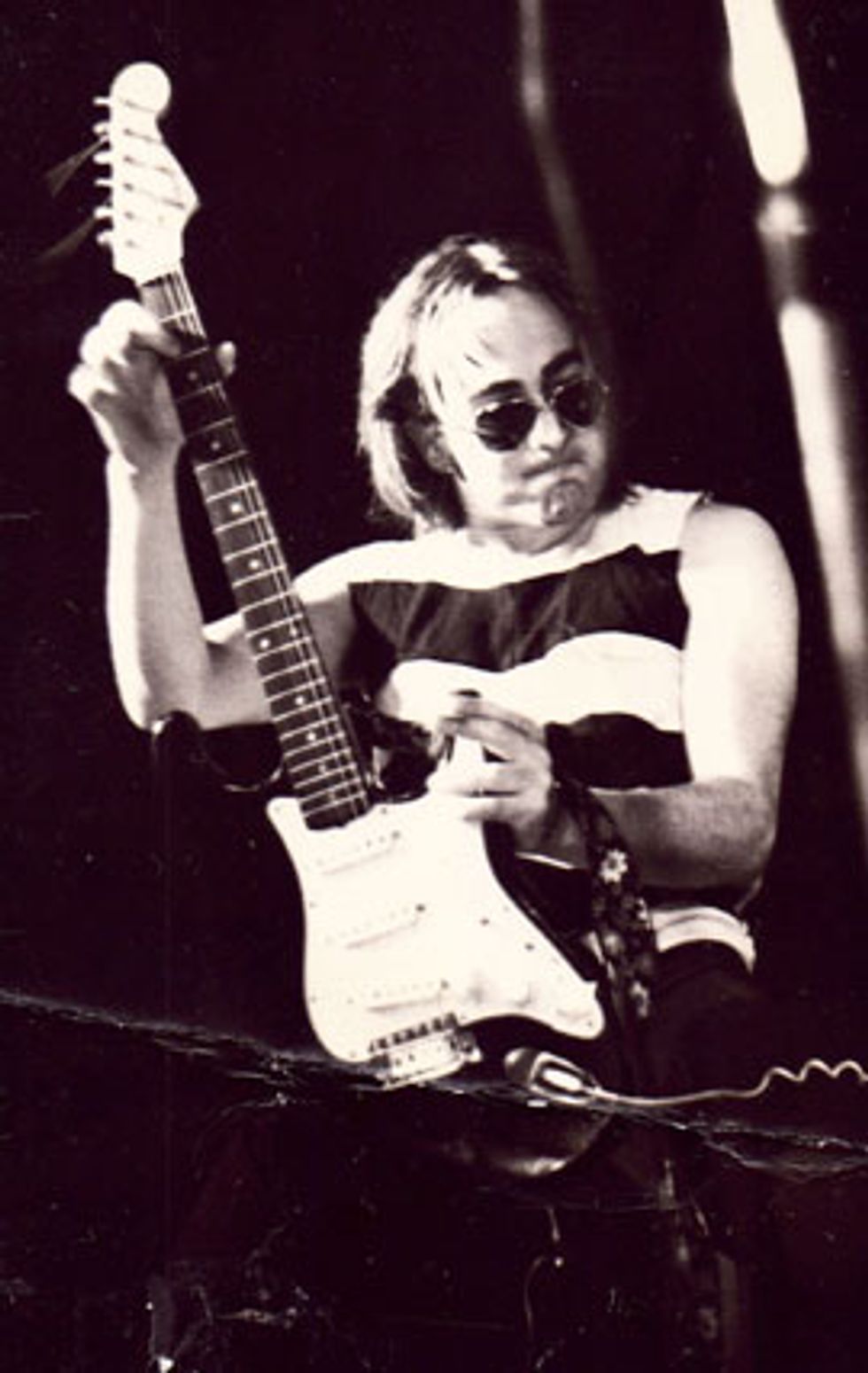

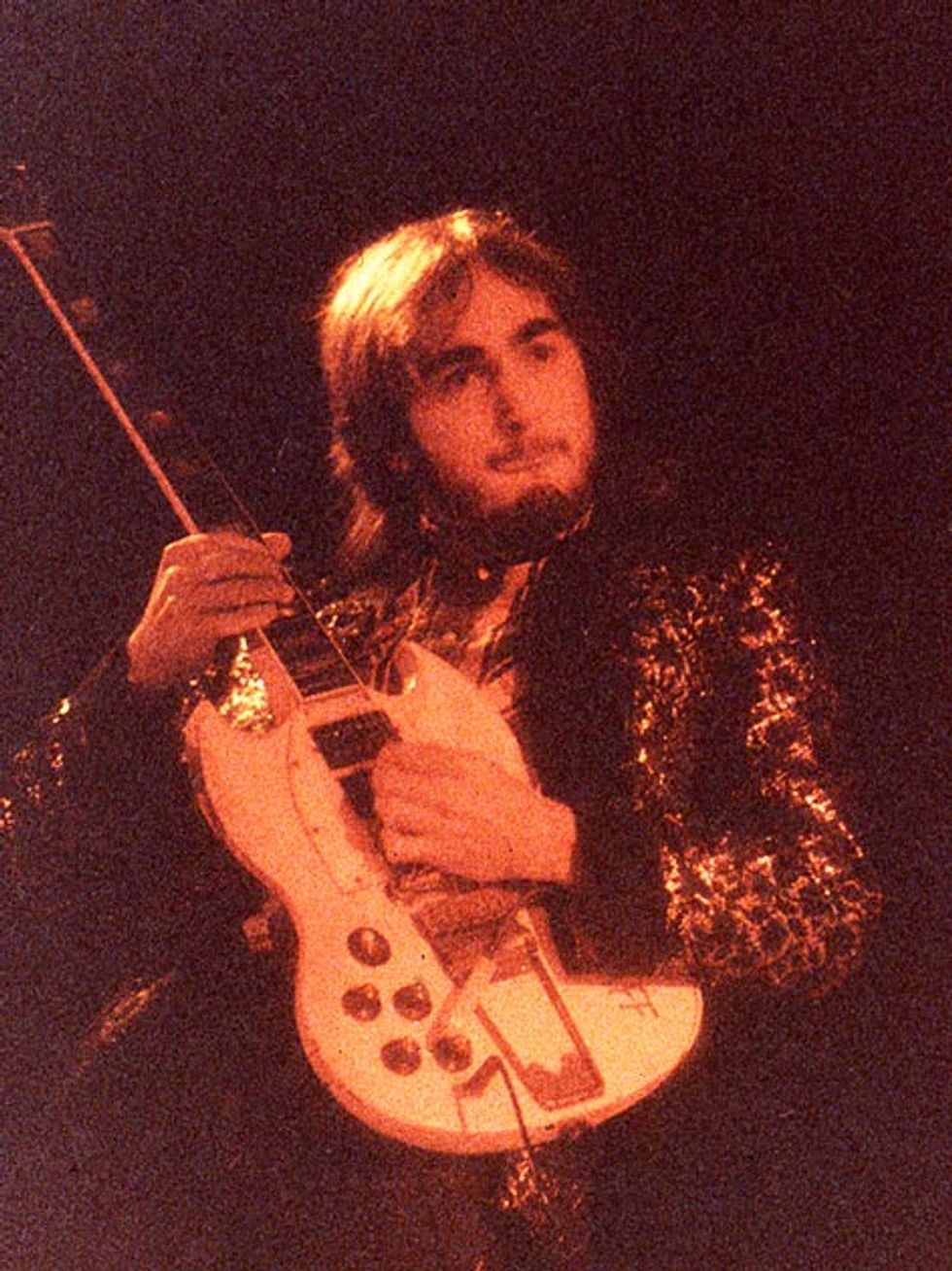

Halsall onstage in 1975 at The Black Swan in Sheffield. Photo by Bob Beecher.

John Halsey, the drummer in Halsall’s bands Timebox and Patto, remembers a different chronology, though Halsall’s achievement was no less impressive. “Ollie looked at a piano keyboard, cut strips of paper to match, and laid them on his bed,” he told Terrascope in 1992. “He bought some vibes beaters with his pocket money and learned to play like that. After a while he told his parents, ‘I can play them now.’ They took him to a music shop in Liverpool, and he could. He turned pro when he was 16.”

Take 5 morphed into Timebox. Their sound was the sound of Swinging London. They wore matching outfits. Their songs were radio-friendly. They signed to Deram (a subsidiary of Decca). And their single, “Beggin’”—a Four Seasons cover—peaked at number 38 in the UK.

Kevin Fogerty, Timebox’s guitarist, quit in 1967, and Halsall took over. He wasn’t a guitarist, but that didn’t seem to matter. He practiced and got good. Fast. “Ollie and I always used to share rooms,” Halsey said in that same Terrascope interview. “He used to sit up half the night just running [scales] up and down the neck. I'd be trying to get to sleep, and he’d be doing his scales over and over.”

Timebox’s evolution followed a similar trajectory to other British bands of this time period: They released radio-friendly singles (including the great B-side, “I Wish I Could Jerk Like My Uncle Cyril”) but got heavier and more experimental in their live performances.

Unfortunately Timebox’s singles failed to chart, which became a problem, and they weren’t a blues band. Their music got more avant-garde, they were more open-ended and improvisational, and they played in odd time signatures. They were zany.

Keyboardist Chris Holmes quit in 1970 and the remaining members, sick of their dual identity, renamed the band “Patto,” after lead singer Mike Patto.

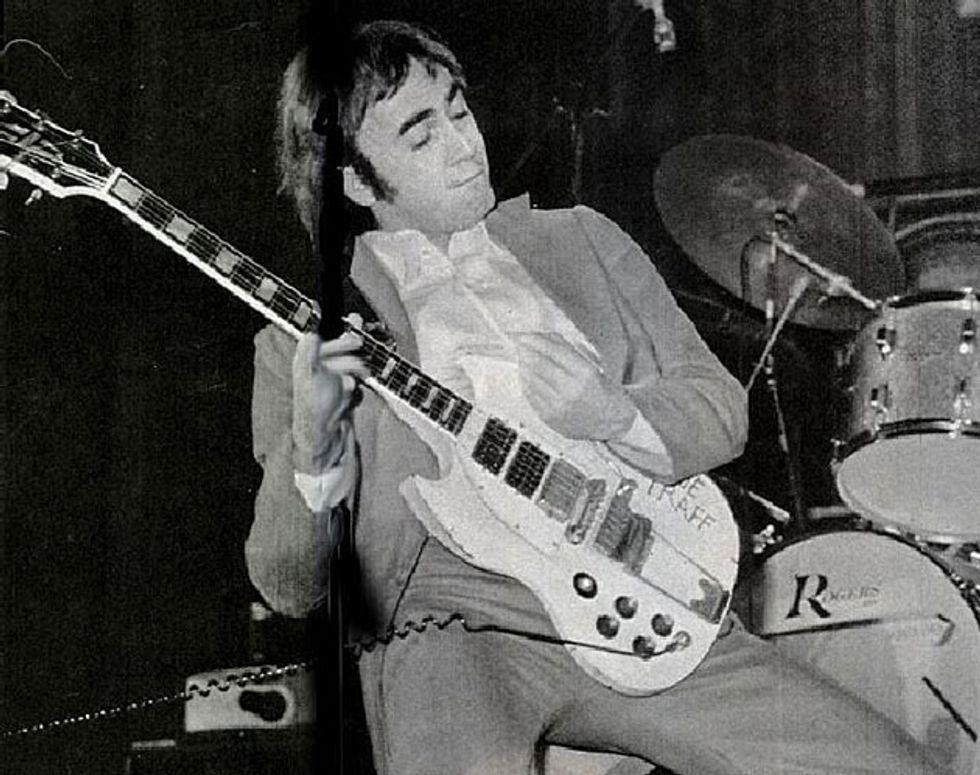

This white Gibson SG Custom was made lefty for Halsall by one of his roadies. Halsall wasn’t the only guitarist to play a white lefty SG: Hendrix had one, too.

Mod Squad

As the guitarist in Patto, Halsall was a monster. He was so nimble that other musicians took notice. “I’m just a simple bloke,” he told Melody Maker in 1972. “But I tend to freak guitarists out, put the willies up them.”

But he wasn’t just fast—his harmonic sense was different. He was a blues-based player, but he wasn’t limited to minor pentatonic runs. He added extra notes, goofed with the tonal center, and left tensions unresolved. And in addition to the notes he chose, he had an eccentric sense of phrasing. Halsall played repetitive figures in unexpected places, took off on tangents mid-thought, and seemed addicted to the unpredictable.

Halsall started playing guitar as a mature and working musician. He already had the skills for making music: a solid sense of time, a trained and developed ear, and an understanding of harmony, chords, melody, and phrasing. He didn’t think like a guitarist, and that made him different.

He also didn’t listen to guitarists. “The only player I find myself listening to is Django,” he told Melody Maker in November 1971. “I tend to listen to horn players and pianists, especially Cecil Taylor. I’d like to play guitar like Cecil plays piano.” He admired Taylor’s power, clarity, and precision, and he purposely wanted to incorporate that into his own playing. “I want to get the infinite power from guitar with his solid hand action,” he said. “That is what I’m working on.”

Patto’s small but fanatical cult following was limited to London and a few towns in Northern England. They made a few radio appearances, too, until the BBC banned them. “They didn’t show up for a radio session,” archivist Barry Monks told Premier Guitar. “The BBC ban was for radio and television—and that had serious repercussions.”

Specifically, it meant that Patto never appeared on the Old Grey Whistle Test (the premier English program for “serious” rock), which hampered their ability to reach a wider audience. “An appearance on the Old Grey Whistle Test would have been a big deal for them,” says Monks, who moderates a website devoted to the Halsall. “But it never happened.”

At the time, it seemed the ban was just a minor setback. From 1971 to 1973, Patto were the next big thing. The New Musical Express said in January, 1972, “If the lip service paid to them from within the confines of the music business were sufficient, then Patto would be giving the proverbial elbow to more established purveyors of electric rock.”

Patto signed to Vertigo (the progressive subsidiary of Phillips), released two albums, toured as the opening act for the Faces and Ten Years After, and gigged locally. Their madcap live shows were legendary, and their musicianship turned heads as well. “Guitar player Ollie Halsall is most definitely the most underrated guitar player in the country at present,” Ray Telford wrote in Sounds in August 1972. “He is also no slouch on any kind of keyboard.”

Patto’s second album, Hold Your Fire, is a guitar tour de force. “The second you hear Ollie’s flash lead guitar you are made aware of the fact that this is no neo-Cream imitation or anything of that kind, but an English rock band with distinctions far beyond those of mortal Americans,” Jon Tiven wrote in his review in Fusion in July, 1972.

Hold Your Fire oozes great guitar playing, but the solo on “Give It All Away” is exceptional. Halsall let loose, and his solo encompasses the traits that defined his style: lightning speed, outlandish yet accessible.

It seemed success was just around the corner. Since Patto’s strength was their live shows, their third album, Roll ’Em Smoke ’Em Put Another Line Out, recorded for Island Records, attempted to capture the magical spontaneity and lunacy of Patto in concert. Halsall plays piano—sans guitar—for about half the album, but his guitar playing on “Loud Green Song” more than makes up for it. To quote a reviewer for the website Julian Cope Presents Head Heritage, “When the Blues had a baby and they named it Rock ’n’ Roll, even they, down-with-the-kids parents they were, could not have foreseen the teenage delinquency of Patto’s ‘Loud Green Song.’ If you haven’t heard Patto’s ‘Loud Green Song,’ YOU HAVE TO HEAR PATTO’S ‘LOUD GREEN SONG.’”

The song in question wails in sonic weirdness. From its opening riff to the lengthy breaks between verses, the twisted tonality, and the abrupt ending, “Loud Green Song” stamped Halsall as a guitarist like no other. The playing is downright nasty. It was raw, naked, unvarnished, and—for 1972—years ahead of its time. It took heavy metal another 10 years to catch up.

Patto toured the U.S. and Australia opening for Joe Cocker. They played the largest venues of their career and were an audience favorite. But in a case of bad timing, Island released Roll ’Em Smoke ’Em Put Another Line Out after the tour ended, and sales were weak. “You know, we absolutely went down a storm on that Joe Cocker tour—played almost every night, some of the biggest venues in the States,” drummer Halsey told Ralph Heibutzki in an article for Ugly Things. “[The album] was released the week after we left—by that time, everybody’s seen another two bands.”

Patto returned to the same small English venues they’d played before they went on tour. The band went into the studio to record their fourth album, Monkey’s Bum, but Halsall’s heart wasn’t in it. He walked out mid-session. The party was over.

Patto never found their audience. Starting as Timebox, they came from the same scene as the bands they toured with, but Patto evolved into something very different. They didn’t write hits. They weren’t a Top 40 band. They weren’t a beefed-up blues band. Patto had more in common with the Mothers of Invention and Captain Beefheart. But L.A. is far from London, and no one made that connection.

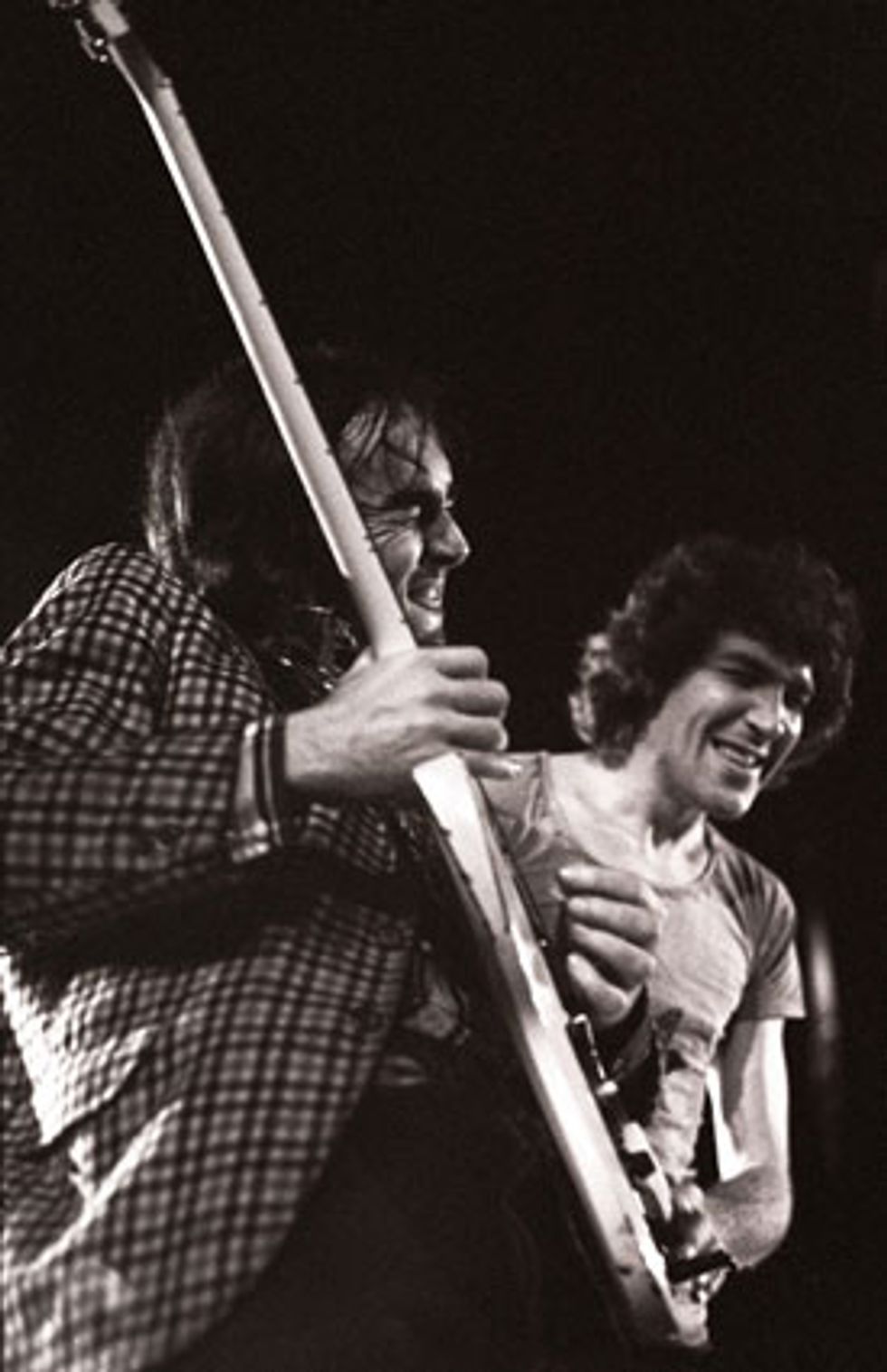

Fans familiar with Ollie Halsall’s guitar work might be surprised to learn he played the “Paul McCartney” guitar parts for the Rutles, a Beatles spoof band. Halsall is shown here jamming with Kevin Ayres at Hurrahs in New York during a 1980 tour.

Post-Patto

Halsall’s next band was Tempest, where he replaced outgoing guitarist Allan Holdsworth. The split was amicable, and for a few weeks Tempest featured both Halsall and Holdsworth. The BBC promoted and recorded a concert of that lineup in London in June 1973 (you can hear it on Under the Blossom: The Anthology, a Tempest compilation).

Halsall and Holdsworth were very different musicians. As Jon Hiseman, Tempest’s drummer and leader, told Dmitry Epstein in a 2004 interview, “Allan was very meticulous, very clear. He had a vision about what he was trying to do. Ollie was a lunatic.” He meant that as a compliment. “In any circumstance he’d find a way to make it work.”

Tempest post-Holdsworth toured as a trio—lead singer Paul Williams left along with Holdsworth—with Halsall on guitar and vocals. They toured Europe and recorded the album Living in Fear, but it didn’t last. Tempest broke up, and Halsall started doing session work. He also began working with Soft Machine’s Kevin Ayers. “I was in AIR London studios, working on the Tempest album, and Kevin was there also,” Halsall told Trouser Press in 1976. “I was just sitting around, and [producer] Gerry Bron had his pocket calculator out, fooling around. Kevin came down the corridor and asked if there was a guitarist in the house. He needed a solo put on a song (“Didn’t Feel Lonely Till I Thought of You”) on the Dr. Dream album.” That was his first session with Ayers. It was an association that lasted until the end of Halsall’s life.

Patto reunited for three sold-out shows in 1975. The concerts were benefits to raise money for the family of a former roadie murdered in Pakistan. After that, Patto—the band—never worked together again, but Halsall and Mike Patto did. Their new band, Boxer, with drummer Tony Newman (Jeff Beck, Rod Stewart, David Bowie) and bassist Keith Ellis (Van Der Graaf Generator, Juicy Lucy) signed a five-record deal with Virgin.

Boxer was a heavier band that had potential to be huge. Its members were seasoned pros with a serious work ethic and financial backing. Their songs were straight-up, in-your-face mid-’70s rockers. The cover for their first album, Below the Belt, was designed to generate controversy and press (a naked woman, spread eagle, with a raised fist covering, well, almost nothing).

But despite the press, money, and support, Boxer didn’t last. After recording their second album, Bloodletting, Halsall was either fired or quit—different people tell different versions. Regardless, with Halsall’s departure, Nigel Thomas, Boxer’s manager, confiscated Halsall’s guitars and amps—including his iconic white Gibson SG Custom—to cover his losses. Halsall was left with nothing. And as a tragic footnote, Mike Patto died of lymphatic leukemia in 1979.

Halsall hit hard times. He still did sessions, but he was broke. He relied on borrowed guitars. He toured the U.S. with John Otway, who’d had a huge U.K. hit, the half-spoken comedy love song, “Really Free.” In an ironic twist, Halsall’s biggest session was as the “Paul McCartney” character for the Beatles-spoof band, the Rutles. However, Halsall’s contribution was anonymous. In the film, All You Need Is Cash, Eric Idle played “McCartney,” lip-synching Halsall’s vocals and miming his guitar parts.

Success in Spain

Despite professional setbacks, Halsall kept at it, spending the ’80s as a musical journeyman. Peers respected him as a seasoned veteran and reliable sideman. He adapted to new styles and trends. And he finally bought a guitar: a cherry red SG that he modified similarly to the white SG Custom from his Patto days.

Halsall worked a lot in the ’80s, and his biggest gigs were with Kevin Ayers and the Velvet Underground’s John Cale. But he didn’t play with reckless abandon like he did with Patto—he stuck to the song. “My style has changed,” he told Guitar Player in April of 1989. “There are less notes than before and the sound is clear.”

In 1980 he toured with Bill Lovelady, an old friend from Southport with a chart hit (“One More Reggae for the Road”). Also in that band was vocalist/keyboardist Zanna Gregmar. When the tour ended, Halsall and Gregmar moved to Spain to be close to Ayers. Halsall was based in Spain until he died.

Halsall and Gregmar also formed a band, Cinemaspop, playing synth-heavy European techno. They were big in Spain. Their recordings didn’t feature guitar, although Halsall played guitar live. And yet, according to Monks, Halsall loved Cinemaspop. “They were successful and made a lot of money,” Monks says.

Ayers recorded Still Life with Guitar with Halsall in early 1992, and they performed in England that April. A month later, Halsall was found dead in his apartment in Madrid, reportedly after suffering a drug-related heart attack. His death was a shock. According to Monks, Halsall was anti-hard drugs, and substance abuse wasn’t something associated with Halsall. Even back with Patto—despite a third album called Roll ’Em Smoke ’Em Put Another Line Out—Ollie wasn’t a big drug user. That album title was just a joke.

A small memorial was set up in Mallorca, the Spanish island where Halsall hung out with Ayers. Except for a small group of loyal fans, most people have never heard of him. But Halsall’s legacy lives on—and grows over time. Halsall rumors abound: A shred label was trying to find him to record a solo album. The Stones considered him as a replacement for Mick Taylor. Eddie Van Halen was a fan. What’s true? Who knows?

But one certainty remains: Halsall was a great guitarist—a true original and a pleasure to listen to. As Andy Partridge told PopDose, “[Halsall’s playing was] like a beautiful gift, where you’re opening a box, and you think you know what might be in it, but then you’re, like, ‘Oh, that is phenomenal! What a lovely little surprise!’”

Ollie Halsall Essential Listening

This clip features Halsall on vibes with Timebox. “Beggin’” was their biggest hit and peaked at No. 38 in the U.K. Halsall’s vibe playing is stellar. Dig the band’s matching outfits.

“Give It All Away” is from Patto’s second album, Hold Your Fire. The guitar breaks are inventive and unusual, but the solo starting at 2:24 is exceptional (and really fast). Keep in mind, Halsall didn’t use effects during this period. His sound is just a guitar and overdriven amps (two Fender combos, usually a Princeton and a Super Reverb, one plugged into the other).

The guitar weirdness starts at 0:50 and just keeps getting better on “Loud Green Song” from Patto’s third album, Roll ’Em Smoke ’Em Put Another Line Out.

A mature and older Halsall plays an unconventional solo starting at 0:55. The sound quality is poor, but this video offers a taste for what Halsall was up to late in his career.

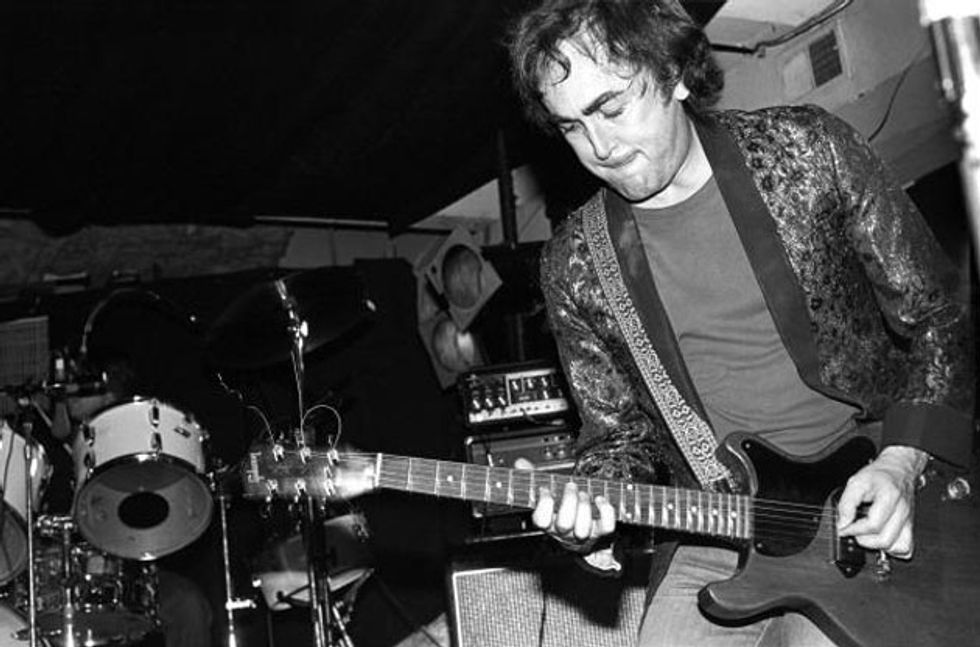

Photo by Lloyd Goodman.

Ollie Halsall’s Ad Hoc Lefty SG

The guitar usually associated with Ollie Halsall was a white 1967 Gibson SG Custom. The guitar came with three humbuckers and a Vibrola tremolo unit.

Since Halsall was left-handed, Barnabus (Barney) Swain, a roadie for Patto, converted Halsall’s SG from righty to lefty. Swain carved a new chamber for the electronics and moved them to the guitar’s new lower bout. Halsall didn’t want the knobs to mirror a right-handed model. Rather, the knobs for the bridge position—on the bottom on a right-handed guitar—were on top next to the bridge. The knobs for the neck position were nearer the floor. The 3-way toggle was kept “upside-down” as well (neck down/bridge up). The original cavity was filled with wood. The new lower horn—part of the double-cutaway—was cut deeper for easier access to the upper frets.

Halsall let the Vibrola arm hang loose, dangling over the bridge pickup, and he dealt with tuning issues on the fly. (In the ’80s, he replaced the Vibrola on a different SG with a Kahler locking system to keep it in tune.)

The words “Blue Traff” were carved into the upper bout. The phrase reportedly paid homage to a never-released album Halsall recorded with Robert Fripp in 1972. Why blue traff? Spell Traff backwards and remove an “F.” Got it? It makes a blue flame when you light it on fire. Boys will be boys, as they say.

Halsall’s SG was found in a repair shop in 2006 and restored to its Halsall-era condition. The complete story of the guitar’s restoration, as well many details provided for this edition of Forgotten Heroes, can be found at Barry Monks’ website/archive for all things Halsall: www.olliehalsall.co.uk/

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.