Discovering the bass, says Esperanza Spalding, was like “waking up and realizing you’re in love with a co-worker.” Although she moved to upright bass at the tender age of 15, the 27-year-old winner of Best New Artist at last year’s Grammys was already a classical concertmaster with 10 years of violin study and performance experience in her hometown of Portland, Oregon.

Switching to bass carried a slightly scandalous whiff in Spalding’s previous circles, but it didn’t matter—the appeal of jazz greats like Slam Stewart, Scott LaFaro, and Leroy Vinnegar had won heart. Indeed, even more than her prodigious talent, heart—her ability to “transmit a certain kind of personal vision and energy that is all her own”—is what Pat Metheny once described as Spalding’s “X factor.”

That certainly extends to her bass playing. As demonstrated on her second album, 2010’s Chamber Music Society, whether she’s playing a 7/8 or 3/4 upright double-bass, Spalding shows a technical command that’s as at home with the colors of Bart—k and Webern as it is with the ghost notes and broad swaths of sound that Paul Chambers laid down on “Kind of Blue.” And then there’s her fretless electric work, which has an energy and phrasing reminiscent of Jaco Pastorius on “Teen Town” and “Come On, Come Over,” with a loaded lower-mid attack and heavily syncopated lines that suggest the middle ground between popping and rest-stroke.

Spalding—a mix of African American, Welsh, Latin, and Native American ancestry— is both lovely and instantly endearing. She’s as likely to express herself humbly as she is to be firm about her many strengths and her point of view. That combination is part of what makes her latest album, Radio Music Society, such a compelling hybrid and such an arresting listen. Fusing Afro- Cuban, bop, chamber music, jazz vocalese, and R&B with the dizzying chanteuse streak of her elastic vocals, the album is shot through with savvy lyrics that take on real-world subjects like racial pride and identity (“Black Gold”), the nature of friendship (“Cinnamon Tree”), and the price of war (“Vague Suspicions”). And then there’s the fact that she sings in perfect Portuguese.

If all that sounds improbably mature and totally kick-ass for someone still in their mid-20s, well, it is. Still, given that Spalding is the first jazz artist ever to win a Grammy for Best New Artist—and the youngest instructor ever hired by her alma mater, Berklee College of Music—it does help cement the less-than-vague suspicion that Spalding is something of a smoldering cross between a Jaco Pastorius and an Adele.

You began on the violin and upright

before picking up electric bass. How

does the one inform the other—what’s

the hand-off?

Functionally, there are a lot of things

that translate across the two, but the

situations I’ve played electric in are so

distinctly electric. I wouldn’t have tried

to do that music on upright, and vice

versa, so it’s hard to tell. I will say that

things that are second nature for me on

upright, I really need to think about

on electric.

Fretless bass is a very difficult instrument

to play well—you almost need

experience with an upright to do it.

Well, I play fretless partly because frets

defy my capacity to understand. Never

having played a fretted instrument,

the frets just… wow—I don’t know

where to begin on a fretted instrument!

With a guitar, I’m down with that. I

get it: For chords, it helps you stay in

the right place. But on the bass, with

melodic movement and lines, it really

trips me up.

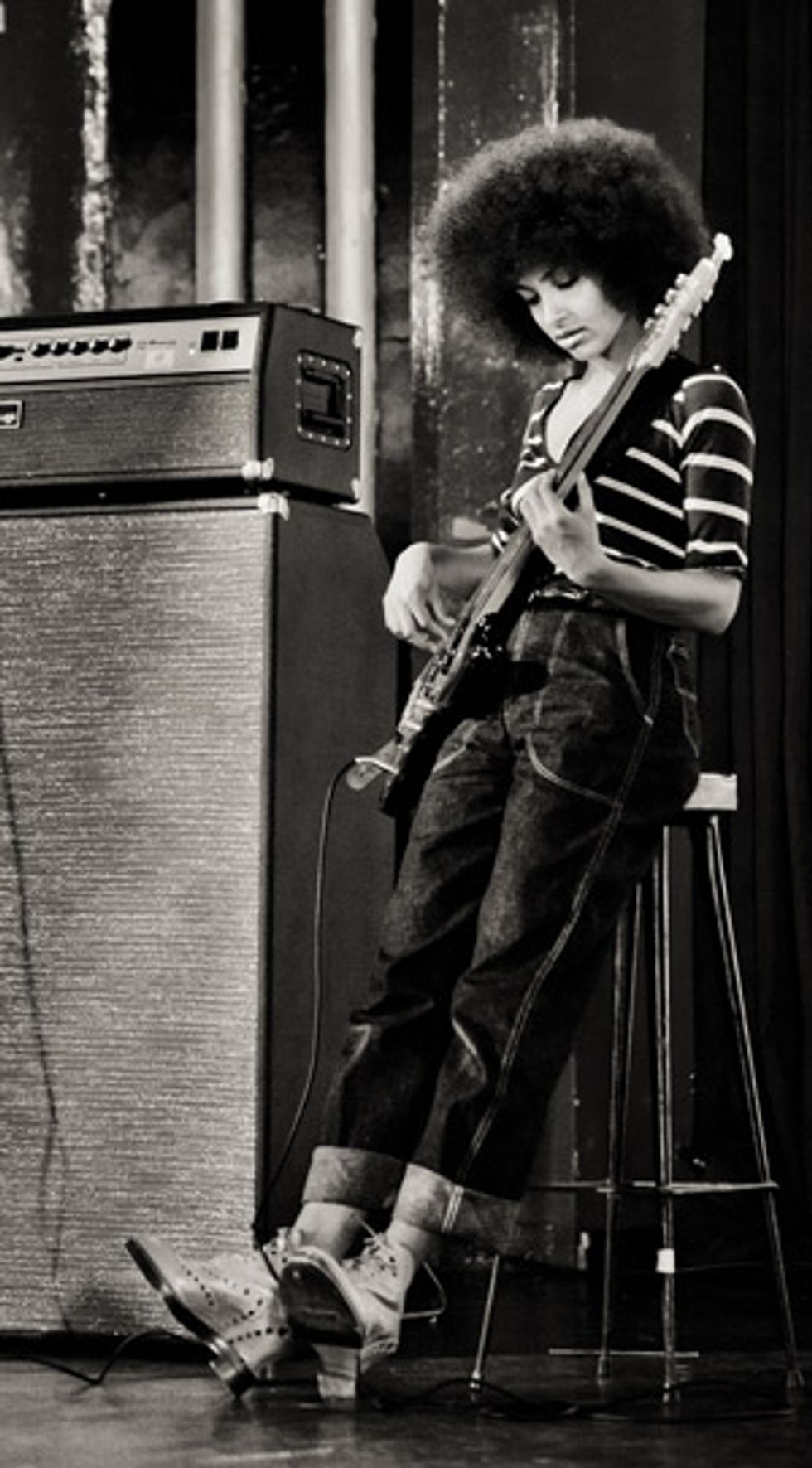

The Fender Jaco Pastorius Jazz

bass appears to be a good fit

for Esperanza Spalding, whose

chops have been compared to the

legendary Jaco. Photo By Carlos

Pericas, Courtesy of Montuno

Why?

It’s a whole different philosophy of being in

tune. If you grow up playing violin, everything

is about how you get to the right note

in time. Then, if you land on the wrong

note, how do you quickly adjust? All these

things really revolve around intonation.

Intonation becomes about distance and

time—how much time do I need to get a

particular distance across the fingerboard?

And your ear guides so much of what you

do when you’re playing a fretless instrument:

So much depends on being able to

quickly hear how close you are to the pitch.

Which instruments are you mostly

playing these days?

For electrics, I’m playing a Fender Jaco

Pastorius Jazz bass and a Godin A5 Semi-

Acoustic 5-string, which has an L.R. Baggs

undersaddle ribbon transducer. The Godin

is really cool—it just sounds beautiful. It

was different for them, and different for

me, so they encouraged me to experiment

with it. For uprights, I play a 7/8 double

bass. It’s the one bass I’ve always used.

Luthiers can’t come to a consensus on who

made it or when, but evidently it was an

orchestra bass for years until the owner

died and the family sold it. It’s just really

alive and really open—super resonant. But

I don’t travel with it. On the road, I just

ask for a 7/8 or 3/4 bass, hope it’s cool,

and go for it.

You’ve played with some legendary musicians,

including Stevie Wonder, Prince,

and Herbie Hancock. But for jazz nuts, a

couple of them—[legendary jazz drummers]

Billy Hart and Jack DeJohnette—

are just … “Holy crap!”

That’s how I feel—woo! I mean, they’re

my friends, and I love and admire them,

so if I feel I have something to offer them

by being on the project, why not invite

them to play on my album? I asked Billy

to play on my album after a gig at the

Village Vanguard, and he said, “Sure kid,

but you’re never going to call me.” But of

course, I did, and he just came in and laid

down that crazy, beautiful groove on “Hold

on Me.” I got to know Jack from doing a

few gigs with Herbie Hancock. We hit it

off—just had a really beautiful rapport as

human beings, talking about music and

life. It was like, “Let’s do this—I’ll play

on your record [DeJohnette’s new Sound

Travels], and you’ll play on mine.”

Jack is such a musical drummer—it’s as if

he’s playing a little orchestra.

That’s something I really like about Terri

Lyne Carrington, too. It’s not like, “I

worked out a bunch of shit on the drums,

and I’m going to play it.” It’s more like she’s

orchestrating around the kit, so it sounds

like multiple percussion instruments being

played at once. And yeah, Jack is the same

way. He’s not locked into patterns. He

comes up with the right combination of

notes and rhythms for the context of every

moment, and that’s really rare.

You take on some pretty potent topics,

and you also do something very few

young songwriters do—you write about

stuff other than yourself.

I talk about myself an awful lot, doing

so many interviews, and I’m just not that

interesting to myself! I find a lot of inspiration

in the people I know and the world

around me, and if I’m going to spend all

this time that it takes to put together a

song that I’m happy with, it’s got to keep

me interested. The songs that capture my

attention—the ones that really feel done in

the end—are the ones where I have to really

dig to find out what it’s talking about.

“Cinnamon Tree” was a real challenge. Sure,

the metaphor was there first, this little nickname,

but how to unpack that, turn that

little phrase into a song and a story about

friendship?

You’ve been quoted as saying you write

songs and albums in fragments, yet your

albums hang together very nicely—

despite being stylistically diverse. How do

you pull that off?

Well, I make a record because the music

seems like it’s got something to tell.

Through the process of unpacking the

songs, step by step, you’re just trying to

do service to the music. So if it seems like

some dissonance is in order, then that’s

what you do. If it’s a good place for a

simple IV-I cadence, I’ll do that. There’s not

a guiding principle that comes from outside

the music. The guiding principle comes

from within each song and from within

each ensemble.

So you take it one song at a time, without

any sort of overarching theme?

Yeah—whether it’s Esperanza Spalding,

Chamber Music Society, or Radio Music

Society, it’s been a song-by-song process,

and then when I look at the final list of

songs, I figure the ensemble will give it

the color that will connect the whole

album. The same is true for bass lines and

bass playing.

I’ve talked about this in terms of playing with [veteran jazz saxophonist] Joe Lovano, regarding playing between the two drummers. With that group, there’s no single approach that works. There’s no specific way of playing that you can count on. I’m just listening. In fact, I try to almost pretend that I’m not playing at all—just to listen, from the outside, to the full sound coming off the stage. Then, as an arranger/ composer, I want to place the bass part so that it will do the most good for the music happening at that moment. And it’s different every night—even the same song can be really different, night to night.

There’s a great line [Thelonious] Monk wrote about how he’d heard a lot of universities had a class called “Communications.” And he said, “I don’t know what that class is for, but I hope they teach deep listening and loving speech!” Communication is ultimately what everybody has signed up for when they get on the bandstand. They are there to communicate honestly and truthfully and even compassionately. You are trying to contribute to a flowing conversation in time, so you listen in order to be better able to speak, and to ask questions, and to make sense.

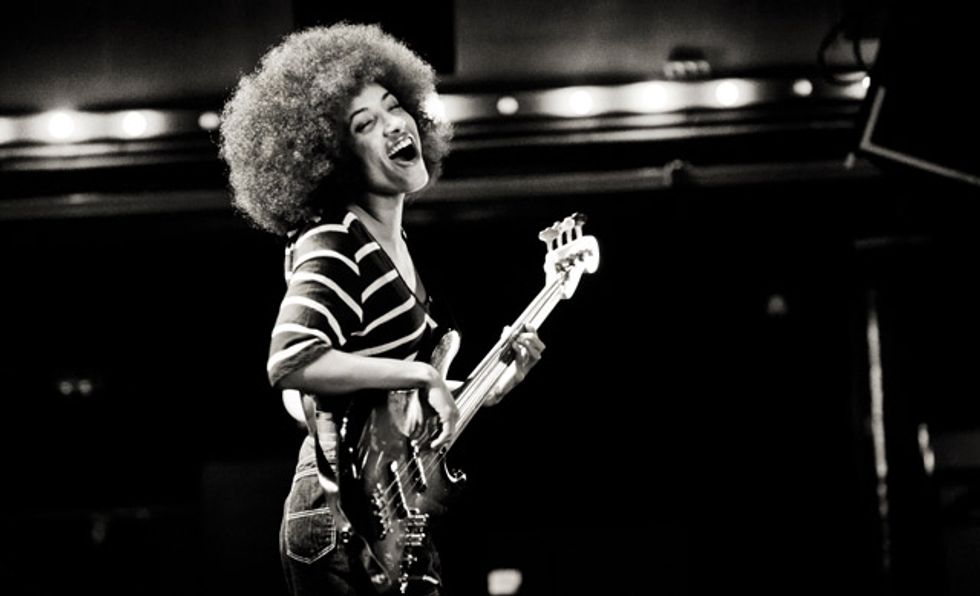

Spalding’s approach to

playing with jazz’s elite is to

listen to the other players

and forget that she’s playing

at all. By Carlos Pericas,

Courtesy of Montuno

What sorts of questions?

You can offer opinions. You can ask,

“Could you describe that further?” Or,

“Have you ever looked at it from this

perspective?” Or you can say, “No, no,

no—I’ve heard that shit before and I don’t

agree!” It’s like there’s a flowing, morphing

conversation, so of course you have

to listen—just like you would if you were

talking to someone you really cared about

and you wanted to know more about what

they were saying. And it’s not just jazz.

Great pop bands are made up of musicians

who exercise all those same skills. That’s the

foundation of music.

YouTube It

Check out Ms. Spalding in action in the following YouTube clips.

Shot live in San Sebastian, Spain, in 2009, this clip shows

Spalding and her band playing a spirited version of “I

Know You Know,” plus some inspired blowing on both

upright and electric.

At this January 2009 tribute to Stevie Wonder at the White

House, Spalding is stunning in so many ways—with her

slippery upright playing, her sultry voice, her classy couture,

and her beautiful smile.

In this gorgeously moody clip, Spalding proves she’s as

adept with a bow as she is playing fingerstyle—and the

vocal work is mind blowing.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)