George Pajon Jr. is pedal-obsessed. For him, time off means hiding out in his studio, working his way through every setting on every pedal he owns—and he owns a lot of pedals—logging each tone he thinks he may be able to use, and making careful notes in order to recall the sound later when needed. When he’s working in the studio or in a rehearsal, he scrolls through his files, pulls up options to share with his many A-list collaborators, and looks for the tone that often makes the difference between a good-sounding track and a hit. He does know the difference, by the way, since he has a regular gig as the touring guitarist with the Black Eyed Peas, and also plays on their albums.

That obsession is also a big part of his writing process with Cairo Knife Fight, his duo with New Zealand-based drummer, vocalist, keyboardist, and kindred-tonal-spirit Nick Gaffaney. “When Nick and I decided we were going to start writing, I started stockpiling sounds,” Pajon says. “I am lucky enough to own my own studio, so I hired an engineer to mic my whole rig and then literally nailed down those mics into the floor so they wouldn’t be touched.” As he experiments with pedals, he runs Pro Tools. “If I stumble on something I like, I scream in the mics, ‘This sounds like a chorus,’ or ‘This sounds like a bridge.’ I mark the session, put it into a notepad on my phone, write the number, and then describe what the sound says to me. There are 72 hours of that.”

Once he has ideas and the skeleton of a Cairo Knife Fight song, he goes back to the cave and starts programming, which takes about one week per tune. He also does everything—each nuance, layer, or quirk—with the understanding that he has to be able to duplicate it onstage, and that also informs the design of his ever-evolving and ever-growing rig.

Cairo Knife Fight has been around since 2004, with two full-length albums and a handful of singles to their name. Since Pajon joined in 2015, they’ve released “Churn,” a single which came out earlier this year. “The first songs we wrote, we will release in the coming years,” he says. “We have 22 finished songs.” On “Churn,” Pajon’s guitar burns with intermittent bursts of djent, thrashing rhythm parts, and incisive melodic lines, while decorated with impressively exact, pop-infused vocals by Gaffaney. His playing, at its most torqued, sounds like sonic flashcards quickly overturned in series—disparate tones tail one another, and yet each somehow seems to fit the tune at hand with surprising logic.

Pajon joined the Black Eyed Peas in 1998. It’s his Dick Dale-style riffing and tone sculpting you hear on the pop outfit’s hit, “Pump It.”

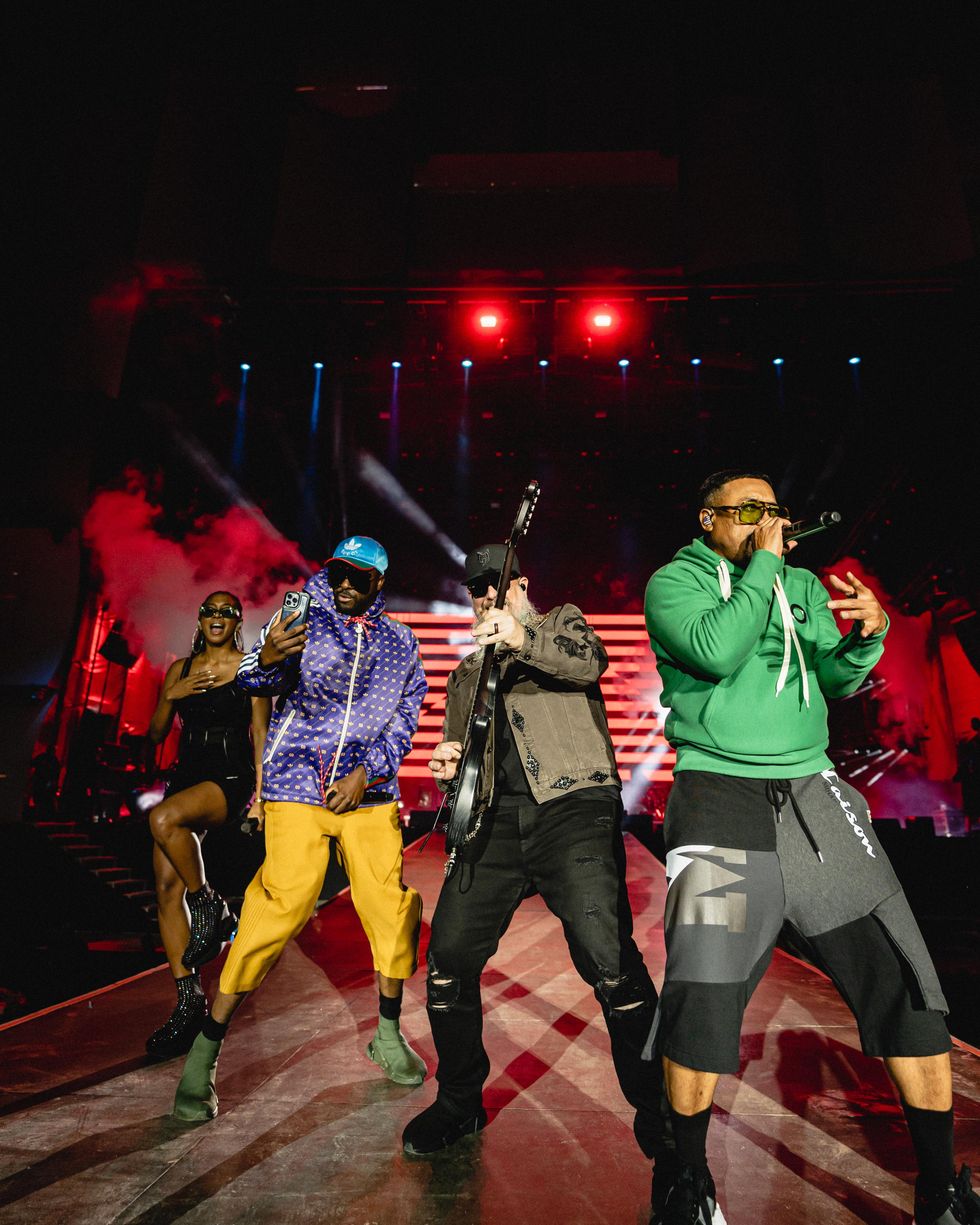

Photo by Sterling Hampton

With Cairo Knife Fight, Pajon approaches arranging like a classical composer. His songs do often have verses and choruses that repeat themselves, but he always makes some kind of variation—be that a tonal shift, an additional riff, a harmony, or taking something out—in order to challenge the listener and keep the song moving. “When you listen to ‘Churn’ from beginning to end, the parts never repeat themselves,” he says. “If you really listen to what the guitars are doing, there’s no cut-and-paste on that song. When I record the guitar parts, it’s a full take. When I double the parts, it’s a full take. I believe that when you listen to a song it should be a ride. The beginning should take you to a different place by the time you get to the end. There’s constant movement in the way I approach writing. That’s why I have all those tools.”

Given Pajon’s passion and dedication to those tools, it’s fortunate that he’s also close with amp legend and tonal wizard Dave Friedman. “I sit with Dave and brainstorm,” Pajon says. “I am really a tech nerd, so I create a PowerPoint spreadsheet with the pedals laid out and how I want the signal flow to be. Dave then tells me, ‘There’s no way we can do this, so we’re going to have to invent something to create what you’re trying to do.’”

Pajon’s rig—the one he uses with Cairo Knife Fight—is already in its 17th iteration, and that doesn’t include the refrigerator-sized unit he has that’s loaded with more than 60 pedals (Friedman wired that up, too). For his work with the Black Eyed Peas, he uses a Fractal Axe-Fx amp modeler and effects processor, which he never stops tinkering with. Pajon is the son of Cuban immigrants and came of age as a guitarist in late-’80s Los Angeles. He hung out on the Sunset Strip when hair metal was the rage, and made the shift in the early ’90s when hair abruptly became grunge. His first loves were Black Sabbath and Iron Maiden, but he discovered a broad range of artists and styles thanks to an open-minded uncle who turned him onto the great guitar-centric acts from the ’60s and ’70s, as well as artists like Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder, and many others.

With Kiwi drummer Nick Gaffaney, Pajon writes guitar and bass parts that he can perform live, loop, and trigger. The duo doesn’t play to backing tracks—everything is done in the moment.

Photo by Michell Shiers

That deep listening exploration came in handy when he first met the Black Eyed Peas. He was with them in the studio for a one-off session, but that quickly morphed into what’s now a 25-years-and-counting relationship.

“I first joined the Black Eyed Peas in October 1998,” Pajon says. “Will [William James Adams, Jr., better known as will.i.am] asked me to come in and play guitar on a song. He was sampling a rock record, and I said ‘Why are you sampling that?’ He said, ‘It’s cool, why not?’ I said, ‘But you’re going to give away all the publishing to that other band. Let me come up with a part that’s similar to that.’ He said, ‘You can play stuff like this?’ I essentially mimicked that style, and he threw away the sample. Then he was like, ‘Do that again,’ and he would give me directions, ‘Change it here, change that chord there.’ That was our relationship.”

That versatility, as not just a player but a master of feels and tones, played a big part in creating “Pump It,” one of the band’s biggest hits. “We were in Japan on tour,” Pajon says. “Will bought a bunch of CDs and he was listening to Dick Dale’s ‘Misirlou.’ I was one of the first guys in the band who had a mobile recording studio—I had the first [Avid] MBOX. At the time I was signed to EMI as a writer, and I would write with different people all over the world. Will knew I had the studio with me, and we were on the bullet train, and he said, ‘George! I need to use the Pro Tools.’ I gave it to him. He samples that Dick Dale song and creates the song ‘Pump It.’

“Fast forward, and we’re finishing that record, Monkey Business, and during that time, it was common for the label to sync one of the songs with a movie or a TV show or a commercial as promotion for the new album. One of the songs they picked was ‘Pump It.’ They had to get clearance from Dick Dale, and he said ‘no.’ Will calls me and says, ‘We have to rerecord Dick Dale’s part.’ I was like, ‘You want me to recreate that?’ I told him, ‘Call Lon Cohen [of Lon Cohen Backline in L.A.], get the same guitar Dick played and the same amp from that time. I’ll do the research.’ We rented those amps and that guitar and I replayed the whole thing. It’s not a sample. It came out so good. Will’s ears are really fine-tuned and he got the EQ just right. But when you listen to that, it’s me. It’s not Dick Dale. We redid those parts for that commercial. In the end, what got released has all the parts that I created for the commercial.”

Cairo Knife Fight sounds nothing like the Black Eyed Peas. It’s heavy and layered, and sits somewhere between progressive metal and grunge. For Pajon, who tells tales of watching the Mars Volta every night with Fergie and members of Metallica while touring with them in Australia in the early 2000s, it’s the perfect sound.

George Pajon Jr's Gear

Pajon has developed a sophisticated system for testing and cataloging new tones and sounds. He spends his days off playing his pedals on every setting possible, then makes a note of how each setting could be used in the future.

Photo by Michell Shiers

Guitars

- Grosh Retro Classic with Evertune Bridge

- Grosh Retro Classic Vintage TKnaggs Severn X with Floyd Rose

- Fender Custom Shop Lush Closet Classic Telecaster with Evertune Bridge

- PRS SC245 with Evertune Bridge

Amps

- Friedman Dirty Shirley Mini

- Friedman BE-100 Deluxe

- Two Rock Custom Reverb Signature V3

- 3 Monkeys Orangutan

- Custom Morgan GP 70R

- Ronin Audio Research K7 GT4-P88

- Form Factor Audio Bi 1000Di

- Form Factor Audio 1B15L-8 cabinet

Pedalboard 1

- Pigtronix Infinity 3

- Devi Ever FX Ruiner

- HexeFX reVOLVER DX

- RJM Mastermind PBC/10 loop switcher

- HexeFX VarioFree The Tone PA-1QB

- Strymon TimeLine

- G-Lab PB-1 power supply

- Midiman Thru 1x4

Pedalboard 2

- Strymon BigSky

- Strymon Mobius

- Pigtronix Infinity 3

- Friedman Buxom Boost

- Friedman Buffer Bay

- Dirty Boy Pedals Fuzzy Boy

- Red Panda Tensor

- HexeFX reVOLVER IV

- EarthQuaker Devices Arpanoid

- ZVEX Fuzz Factory Vexter

- Beetronics Swarm

- Friedman Fuzz Fiend

- CostaLab Booster Plus

- Malekko Downer

- Fortin Mini Zuul

- EarthQuaker Devices Bit Commander

- RJM Music Mini Effect Gizmo X

- Strymon Zuma

- Strymon Ojai

Bass Amps Pedalboard

- JHS Little Black Amp Box

- Voodoo Lab Control Switcher

- Boss BB-1X Bass Driver

- Electro-Harmonix B9

- Disaster Area Designs DMC.micro

- Chase Bliss Blooper

- Darkglass Alpha Omega Ultra

- Source Audio C4 Synth

- RJM Music Mini Effect Gizmo X

- Strymon Zuma

Strings & Picks

- D’Addario, various gauges

- V-Picks Nexus

Since the band is just a duo, loopers are essential when playing live. “On my current pedalboard, I have 10 loopers, if you count all the pedals that actually have a looping function. But I am only looping with three of them,” he says.

Pajon also has a wall of amps, and a guitar tuned to A–D–G–C–E–A to cover the bass parts, which are run through a separate bass amp and pedalboard. “When I am writing a part, it has to be a layer that I can trigger later,” explains Pajon. “It can’t be a 10-bar layer or a long layer that plays through the whole song. It has to be something that only happens for a bar because I need to be able to trigger it live. We don’t do anything to playback. Everything is done live. When we record, I do minimal overdubs to create more of a sonic landscape, but when I do those overdubs I am very conscious that I have to recreate that sound live, whether it’s putting it in a looper or me actually playing it.”

Pajon’s attention to detail, dedication to finding the correct sound, and innate compositional sense—regardless of the genre or project he’s working on—help explain his longevity in the industry and his ongoing working relationships with a variety of artists. His Grammy wins and other awards testify to those qualities.

“I am not a side guy with the band,” he says about his longtime association with the Black Eyed Peas. “Those are my parts. The reason I’ve been in the band so long is I’ve been playing my parts this whole time, that I wrote, that I played on those records. I was in the studio with them creating this music. And that all started from my knowledge, from my uncle turning me on to a whole new flavor of styles.”The Violence of Action Live at Kingsize Soundlabs

At this live studio session with Cairo Knife Fight, watch Pajon’s right foot as he almost constantly loops and triggers parts.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)