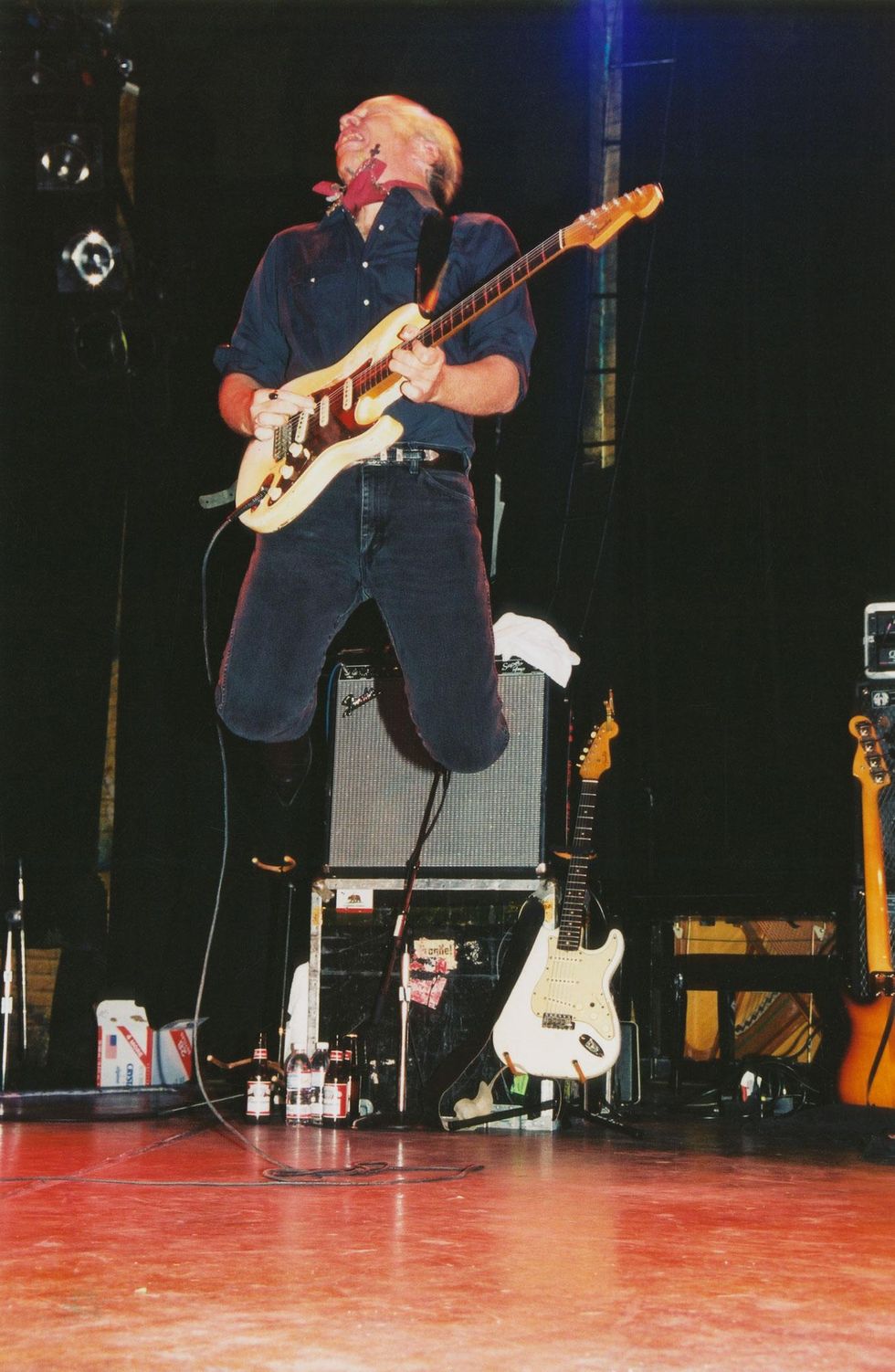

Is Dave Alvin a guitarist or a medium? Listening to him play live, it’s hard to decide. Sure, there’s a custom copy of his beloved ’64 Strat in his hands, pumping loud and salty through an ’80s, Paul Rivera-made Fender Concert. But, rather than simply playing, he seems to be channeling every foundational 6-stringer from the 1940s through the 1960s.

As Alvin revisits songs from his catalog with the Blasters, or his two recent albums with his brother, Phil, or from his brief stint with the band X, or his own deep discography of nearly 20 albums, ghosts are audible in his aggressive thumbpicking. Amidst the cascading melodies, pointed accents, and transcendent dialog of his solos are flashes of everyone from Carl Hogan to Pete Cosey. Alvin explains it this way: “My playing is a combination of Sun Records, Johnny ‘Guitar’ Watson, Chess Records, T-Bone Walker, and that kid with his first guitar in the garage. I try to approach it like that, because, to me, guitar is a magical thing.”

“My earliest memories are of sitting in my Mom’s Studebaker and spinning the dial. Southern California was wide open, musically.”

There’s more to Alvin’s magic than his ability to draw on history or haints to shape a style that shakes every centigram of meaning from each note. He’s also a profoundly good songwriter, in the North American tradition that extends from Tom Waits, Leonard Cohen, Bob Dylan, and Jack Elliott to the original cowboy poets clustered around their campfires with guitars. Alvin’s songs evoke the open expanse of the old frontier and its modern landscape, as well as the heat and diesel of factory towns and the working-class people who occupy them. Just scrape the surface of the 67-year-old’s catalog—his recent releases, the compilation From an Old Guitar: Rare and Unreleased Tracks and the reissue Eleven Eleven, are a good place to start—and the American spirit resonates through what you’ll find. Over the decades he has written about the deaths of Hank Williams (the Blasters’ “Long White Cadillac”) and Johnny Ace (“Johnny Ace Is Dead”), the pain of love’s irrevocable loss (“Harlan County Line”), the wilds of the gold rush (“King of California”), the gilded age of labor unions (“Gary Indiana 1959”), life on the margins (“Thirty Dollar Room”), and the quiet desperation of hearts fading cold, in X’s most poignant song, “4th of July.”

Dave Alvin - Murrietta's Head

“The first songs that struck me when I was a kid were all stories,” Alvin explains. “‘El Paso’ by Marty Robbins, a lot of the Coasters’ records, Elvis, of course, and Carl Perkins’ ‘Blue Suede Shoes.’ There was a plethora of story songs in the ’50s, in a variety of genres. Whether it’s ‘Saginaw, Michigan’ by Lefty Frizzell or ‘No Particular Place to Go’ or ‘You Can’t Catch Me’ by Chuck Berry. What attracted me to story songs is you can say a lot of stuff, without hitting people over the head. You don’t have to go, ‘I’m against this’ or ‘I’m for this,’ because then you become a one-dimensional songwriter. In a story, you kind of slip it into people subconsciously. It’s a little sneaky, but, since Aesop’s Fables, telling stories makes sense of the world. If you go back and listen to all the great folk songs—I mean real folk songs, like ‘Black Jack David’ and ‘Shenandoah’ … themes that have been around for centuries—they’re telling stories.”

Alvin ascribes his songwriting prowess to “trial and error. When I first started writing songs, I had to—unlike the average singer-songwriter—sell them to the Blasters, and they were very strict, because for them doing original material, like ‘Marie Marie’ and ‘Border Radio,’ was outside of their comfort zone. Bringing in original work was scary. My brother, Phil, and I would have big arguments over chord progressions. We had a couple of fisticuffs over minor chords, and so I’m reticent to this day about bringing in new songs. I still expect the Blasters’ reaction.”

The Alvin brothers grew up in Downey, California, just south of Los Angeles. “Nineteen-fifties Downey was different than ’60s Downey,” Alvin relates. “In the ’50s, before the freeways and all had taken over everything, it was semi-rural. There were a lot of orange groves and people were riding horses. There were areas around the San Diego River that were literally wild. And there was AM radio, which, of course, continued into the ’60s. My earliest memories are of sitting in my Mom’s Studebaker and spinning the dial. Southern California was wide open, musically. Whether it was on the radio, or on TV, or in the local restaurants, or lounges, or bars, you could hear everything from Western swing to rhythm and blues to rock ’n’ roll. There was a lot of surf music, and I don’t mean the Beach Boys variety. I mean the Fender Jaguar, a Fender Strat, a Fender Mustang, a Fender P bass, and a drummer kind of surf music—no vocals. I have really pleasant memories of waking up on Saturday mornings and hearing two or three surf bands in the neighborhood, all rehearsing in their garages.”

A close-up view of Alvin’s ’64 Strat. Although the guitar has a vibrato bridge, Alvin, who plays hard, prefers to eschew it onstage.

Photo by Chip Duden Photography

But Dave and Phil also pursued another important path to musical enlightenment. “The story goes that if you were Black in Mississippi, you went north, and if you were Black in Louisiana or Texas, you went west,” Alvin explains, “because there were so many aerospace jobs and a slightly ... slightly … less segregated vibe out here. My brother Phil and I were little record collectors, collecting 78s and 45s, so we loved blues records, and we figured out that not only were some of these people still alive, but they were playing a mile away. If you didn’t act like an idiot, you could maybe sneak into a bar and see ’em, and that’s what we started doing.”

“I was learning; it was rudimentary, but it was good stuff: Chuck Berry, Carl Perkins, Johnny ‘Guitar’ Watson. Put those together and it worked.”

With a neighborhood full of bands and a head full of blues, R&B, and primal rock, the Alvins formed a series of groups. Or, at least initially, Phil, who is two years older than Dave, did. Most of these bands played primarily in the garage, and eventually Dave was allowed to join on sax and flute—although he was also coming up on guitar. One night, he got his lucky break. Phil’s band was booked to play a wedding and needed another guitarist. Dave was called in. “I had an early evening gig, playing at a mental hospital in Long Beach with my own little noisy band,” he recounts. “After we were done, I packed up the Twin and the Les Paul knockoff I had borrowed, and I drove to this wedding reception, and the people loved it. Bill Bateman was playing drums, and that was the first gig of what became the Blasters.”

Inspired by his blues heroes, Alvin uses a thumbpick much like most plectrum-employing guitarists tend to use a flatpick. It’s one of the reasons for his pointed attack and ultra-responsive tone.

Photo by Chip Duden Photography

The Blasters were a sweat-soaked speedball who roared onto the L.A. punk turf in ’79 alongside X, the Germs, Black Flag, Fear, the Circle Jerks, and pretty much every other outfit in Penelope Spheeris’ documentary The Decline of Western Civilization. With their dirty roots in gut-bucket American music, perhaps they were most akin to the Delta-blues-inspired Gun Club, who were also on the scene. But they had muscle and crunch and focus that made them unique. Roughly a year into their tenure, after befriending blues legends like Big Joe Turner, Sonny Terry & Brownie McGhee, and T-Bone Walker, they added one to their band: tenor saxist Lee Allen, who was a key figure in the development of rock ’n’ roll in the ’50s as part of New Orleans’ studio community.

With Phil as vocalist and Dave as songwriter and spark plug, the Blasters played hard and constantly. “What happened onstage was, my brother and I had developed two totally different types of guitar playing,” says Alvin. “His was based on fingerpicking but also he wasn’t a single-string guy. He could do it, but it wasn’t his deal, where it was mine. Because I was learning; it was rudimentary, but it was good stuff: Chuck Berry, Carl Perkins, Johnny ‘Guitar’ Watson. Put those together and it worked. Even my brother had to admit it. He was like, ‘We got something here.’ Our friend, the late blues harmonica player James Harman, knew that I needed a guitar if we were gonna have this band. In a Santa Ana, California, pawnshop, he bought a ’64 Fender Mustang for me, for, like, $70. That would have been around March of ’79.”

When the Blasters made their first album, 1980’s American Music, “James had a white ’61 Strat that he swore belonged to Magic Sam, so that’s what I played on that record. And then on the first album we did for Slash Records, the one with the sweaty face on it [1981’s The Blasters], James brought me a ’56 Les Paul goldtop. The Mustang didn’t really appear on records until the second Slash album, Non Fiction.” And for ’85’s Hard Line, Alvin played a ’51 Broadcaster owned by the band’s guitar tech, who went by Tornado. “I was a fry cook,” Alvin notes. “I didn’t have money for fancy guitars and amps, and, if I did, I wouldn’t have known what to buy.”

The classic ’80s Blasters lineup, from left to right: drummer Bill Bateman, pianist Gene Taylor, Phil Alvin, bassist John Bazz, Dave Alvin with his ’64 Strat, and the legendary saxist Lee Allen.

Photo courtesy of Dave Alvin

That Mustang, currently on display at Nashville’s Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, became a stage favorite. “It was light and very good at deflecting beer bottles,” Alvin says. “If you look closely at that guitar, you’ll see where there is a slash across the upper cutaway. That is from a beer bottle at the Cuckoo's Nest [in Costa Mesa], when we were opening for the Cramps in, like, January/February 1980. Blammo! And if you look closely at the paint job, you’ll see glass embedded all over that guitar, from me holding it up going, ‘Not gonna get this guy, pal.’”

“I didn’t have money for fancy guitars and amps, and, if I did, I wouldn’t have known what to buy.”

Seeking a less combative home for his songs, Alvin left the Blasters in 1986—although he’s played reunion shows and tours with the band since, and recorded two duo albums with his brother. The next few years were busy as he shifted toward building his own outfit. He replaced guitarist Billy Zoom in X, and contributed “4th of July” to X’s 1987 album, See How We Are. Alvin had started his musical association with John Doe and Exene Cervenka from X in 1985, when he joined them in folkie spinoff the Knitters for the album Poor Little Critter on the Road, and he pitched in again for the follow-up, The Modern Sounds of the Knitters, 20 years later. In ’87, he also released his first solo album, Romeo’s Escape, which added new compositions to reprised versions of the Blasters’ “Jubilee Train,” “Long White Cadillac” (which Dwight Yoakam also cut), and “Border Radio,” and allowed Alvin to begin his journey as a vocalist.

Thirty-six years and 14 studio albums later, he has a singing voice like polished oak, with the warm tone and wise phrasing of a seasoned barroom confidant, intent on getting every nuance of his stories across. He also has a Grammy, for his 2000 album Public Domain: Songs from the Wild Land, and two more nominations, and starting in 1995 began publishing his writings: two collections of poems and lyrics, and last year’s New Highways: Selected Lyrics, Poems, Prose, Essays, Eulogies, and Blues, which covers all those categories as well as poignant autobiographical tales.

Dave Alvin’s Gear

The Blasters were known for their sweat-soaked, high-energy performances. Here, Alvin’s playing through a Fender Super Reverb, before his switch to a Rivera-built Concert.

Photo courtesy of Dave Alvin

Guitars

- 1964 Fender Stratocaster (studio only)

- Replica of his ’64 Strat built by Drac Conley (live)

Amps

- Rivera-built Fender Concert (live)

- Fender Vibroverb reissue (recording)

Effects

- TC Electronic Hall of Fame Reverb

- Boss BD-2 Blues Driver (modded)

Strings and Picks

- D’Addario EHR350s (.012–.052)

- Thumbpick

For many of those years, Alvin’s 6-string companion was an ivory 1964 Stratocaster he’d purchased in the early ’80s. “I needed a great all-around guitar,” he says. “It took me a while to get over my gun-shyness about taking it out on tour and all that. But once I got used to it, our relationship together deepened. I started figuring out what it was capable of doing, and what I was capable of doing. But it eventually got to where the rosewood on the fretboard was just a veneer, so one of my dear friends, Drac Conley, built me an exact copy. Because I knew my Strat had to be retired from the road. I hate to say it’s even better, but it’s capable of more stuff.”

These days, Alvin’s clean tone, with just the right amount of crunchy breakup and crisp, punchy attack, is a signature committed roots music fans immediately recognize. That attack is mostly the result of his furious thumbpicking. “When I was a kid going to see certain players at the Ash Grove [a now-gone L.A. club that focused on songwriters], when I was trying to figure out this magical thing called guitar playing, I would see Reverend Gary Davis—one night on a double bill with Johnny ‘Guitar’ Watson, and they were both playing blues-based music from an entirely different direction, and they were both thumbpick players. And then Brownie McGhee would use a thumbpick. I’d see people like that and wonder ‘what is that?’

“My brother played with no picks, but my thumbs were too sensitive to pull that off. Then, I had this other problem: I was clumsy with a flatpick. I can hold a flatpick and strum, but to do anything else? So, when I really started trying to be a serious guitar player, I gave up on flatpicks,—‘Get rid of this shit’—and the thumbpick came absolutely naturally to me. And so, what I’ve done for years is, I use a thumbpick and on my index finger I have an acrylic nail. Not one of the press-on ones. It’s one I’ve built up with whatever vile stuff they use. And because of the strength of the index fingernail, I could really make use of what the guitar can do. If I really want to play an aggressive solo, I will hold the flat side of the thumbpick with my index finger, as if it’s a flatpick, and bend the notes doing that, so it gets extra push. If it’s a quieter song, I’ll use the index finger only to play single-string solos. Or I will play chords with only the index finger or use the skin of the middle finger to strum if I’m doing a tender ballad.”

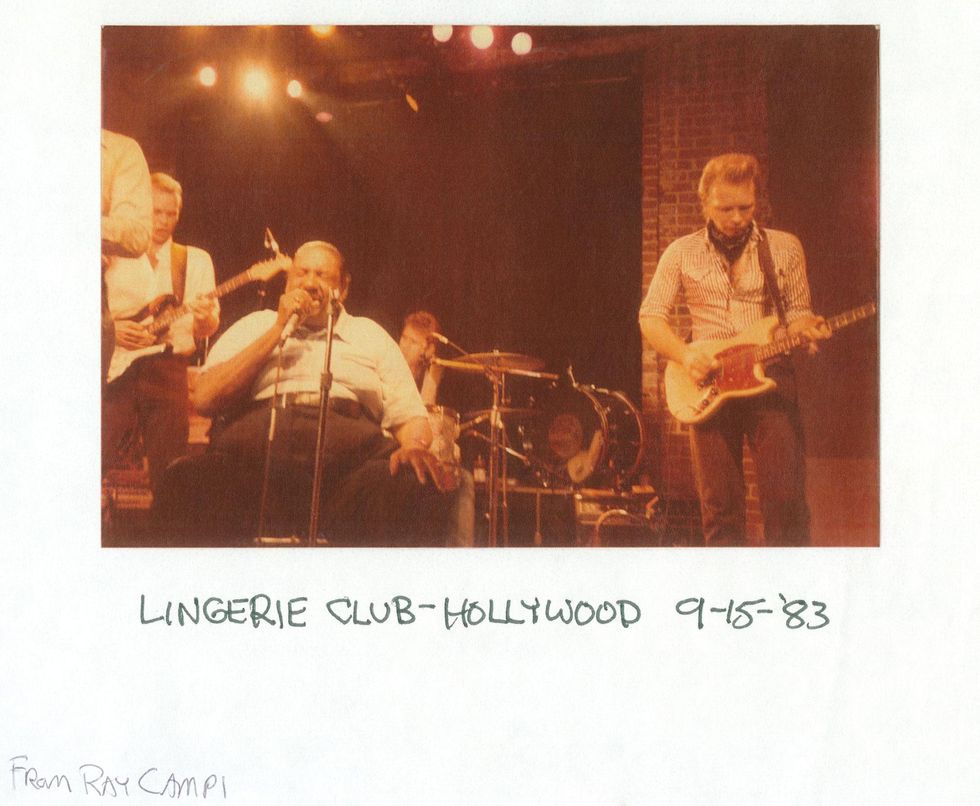

The Blasters back up the great blues shouter Big Joe Turner in 1983 at Club Lingerie, a Sunset Strip venue that was an essential part of the L.A. punk and alternative rock scene. The room closed in 1995.

Photo courtesy of Dave Alvin

His only pedals are a TC Electronic Hall of Fame Reverb and a Boss BD-2 Blues Driver. “Once I start singing, I don’t want to have to worry about what my feet are doing,” he says. “I can take my pinky and slide up the guitar volume, or move the pickup selector to get different tones, but when I’m on stage it’s so exciting that I can’t bother with pedals.”

His other ace is volume. Alvin opens up his amp so its full voice can be heard, and he can achieve sustain, feedback, ringing overtones, and distortion organically. “In one of my road cases, there’s a sign that I made, apologizing for the volume and the damage, but if you’re gonna sit there,” he says, chuckling, “you’re asking for it.”

In 2020, Alvin opened up another new vista, by revisiting a different kind of old music: psychedelia. Working as the Third Mind, Alvin and cohorts Victor Krummenacher, Michael Jerome, and David Immerglück tore a page from the paisley textbook and covered songs by the Butterfield Blues Band (“East-West”), Alice Coltrane (“Journey in Satchindananda”), the 13th Floor Elevators (“Reverberation”), and other twisted troopers. It’s elegant and visceral, and was likely a surprise to many of Alvin’s longtime fans, but Hendrix is also part of his DNA, even if he found it unapproachable until now.

“In one of my road cases, there’s a sign that I made, apologizing for the volume and the damage, but if you’re gonna sit there, you’re asking for it.”

“I’m a barroom guitar basher, but I thought, ‘Let's go down the rabbit hole,’” Alvin says. “When I was around 12, I saw Jimi Hendrix twice, and about a year and a half later, I saw Big Joe Turner and T-Bone Walker with the Johnny Otis Orchestra, and those were the nights! With The Third Mind, I’m less Jimi imitator than using techniques he and Michael Bloomfield used, like manipulating the pickup selector and leaning into the volume.”

That same year, he was almost permanently sidelined by colorectal cancer. He’d spent nearly 12 months on the road and was feeling exhausted. “I was thinking, ‘Maybe I just can’t do this anymore,’” until his diagnosis cleared up the mystery. The cancer had migrated to his liver as well.

Dave Alvin & The Guilty Ones "Harlan County Line"

Dave Alvin leads his band through “Harlan County Line,” the opening track on his Eleven Eleven album—rife with his deft thumbpicking and snappy, biting, clear tone.

“It was extremely difficult,” Alvin allows. “The chemotherapy caused this terrible neuropathy in my feet that still hasn’t gotten better, and they kept saying ‘Well, it’ll take about another year,’ but my hands.… I could not play guitar for about seven months. It was too painful. Touching the guitar was razor blades because my hands were swollen. I won’t say that I had to completely relearn how to play guitar, but I honestly had to teach myself how to play guitar again. The synapses weren’t firing correctly for a long time—between the fingertips and the brain. So, it meant playing a lot of scales, which I still do now. And the scales really helped the neuropathy in my hands, which are no longer swollen. I’m able to play shows. I’m about 90 percent where I was before the chemotherapy.

“It’s not like I’ve ever said, even when I wasn’t sick, ‘I don’t need the practice, I’m pretty good, I can outplay that guy,’” he continues. “I’ve had my ass handed to me by so many guitar players over the years that I’m still just.… Well, by the time I kick the bucket, I would like to say I don’t suck. I wanna be the best as I can be on guitar.

“The one thing I will say is that I’m very lucky, in that I’ve had fans that have stuck with me through a lot of changes. But all of my changes have been organic. I’ve stuck to my guns, taking, basically, the same idea we had when we started the Blasters to the extreme: 'Let’s see how long we can do this and not work a day job.'”

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Luis Munoz makes the catch.

Luis Munoz makes the catch.