Guitars heroes don’t just play guitar. They live it, breathe it, and love it. And their lifelong fandom extends not only to the instrument but to the players they share it with. We asked 17 of today’s most interesting, inventive guitarists in a wide span of genres about their favorite peers. Their answers are thoughtful, heartfelt, and fascinating—providing insight into not only who they admire but the qualities in their heroes’ playing that inspire them, which in turn reveals much about what they love about guitar. So, plug in and read on!

Buddy Miller on Marc Ribot

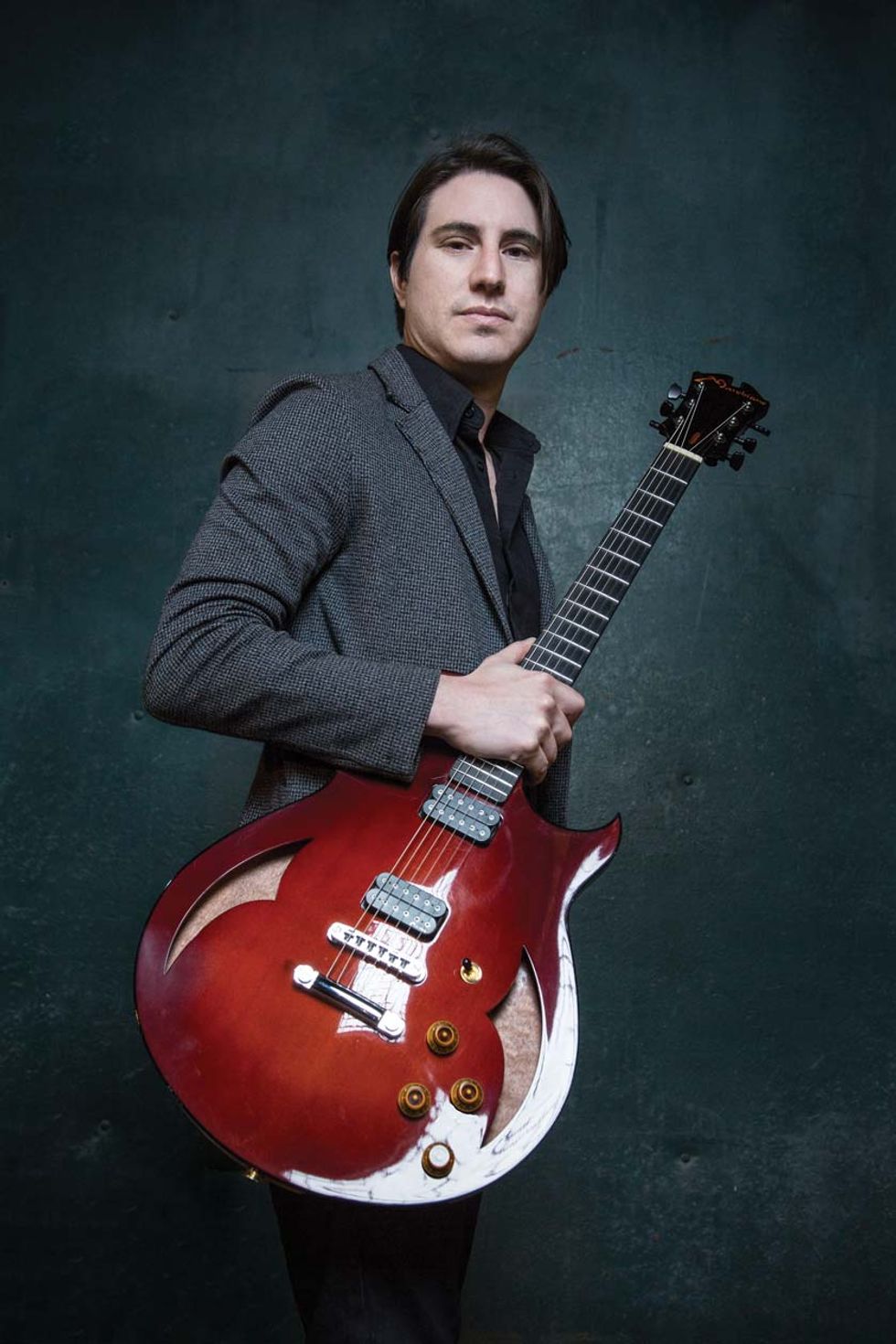

Snarky Puppy’s Chris McQueen on Isaiah Sharkey

Gilad Hekselman on Mike Moreno

Photo by ShervinLainez

Baroness’ Gina Gleason on Big Thief’s Adrianne Lenker

Photo courtesy of Abraxan Hymns

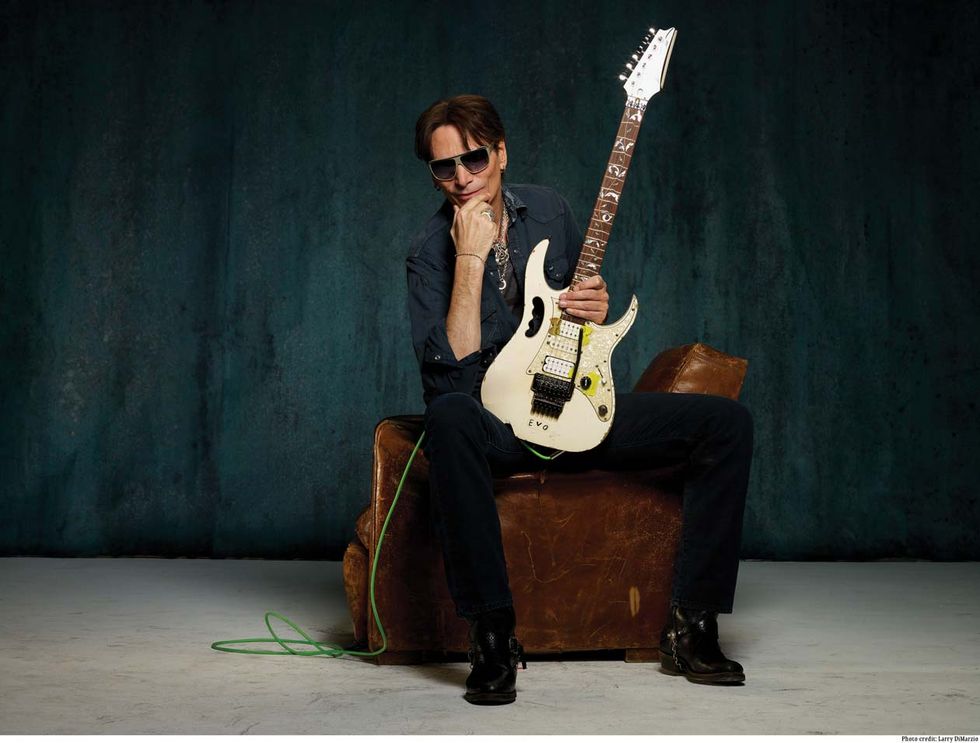

Photo by Larry DiMarzio

Joe Satriani on Steve Vai

Photo by Joseph Cultice

Photo by David Robinson

Baroness’ John Baizley on Converge’s Kurt Ballou

Photo courtesy of Abraxan Hymns

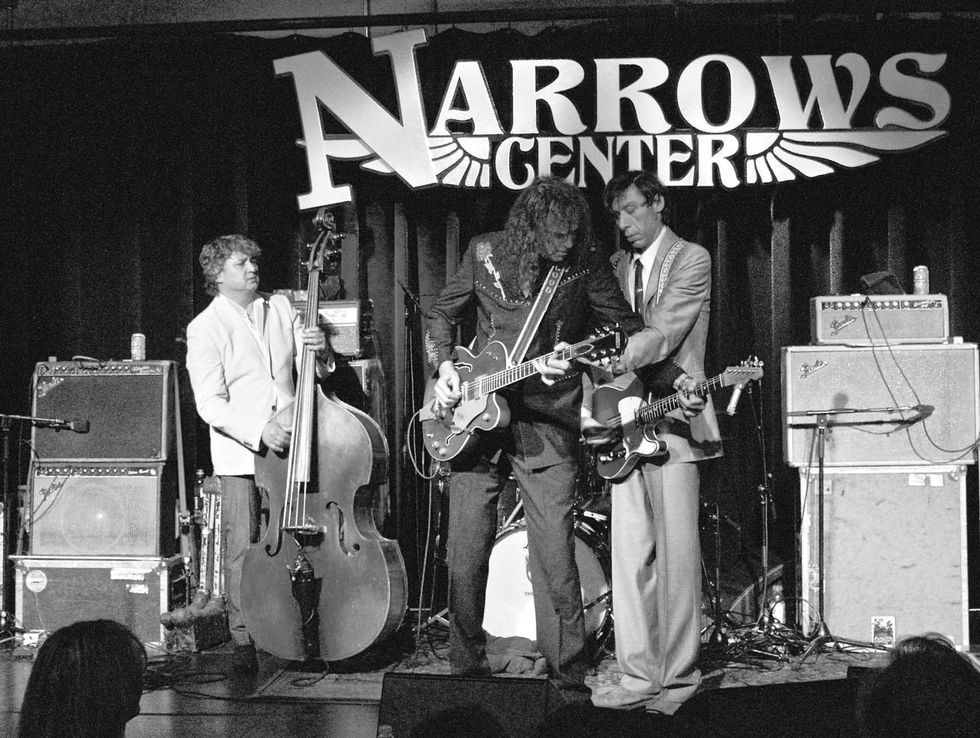

Photos by Janis Tillerson (left) and Chris Sikich (middle)

X’s John Doe on Kevin Smith, Kelli Mayo, and John Bazz

Photo by Autumn De Wilde

Kelli Mayo from Skating Polly only uses three strings on her custom Fender, but that’s all she needs. She follows the punk-rock ethos where anything is possible. I truly love her fearlessness and innovation. I play chords on electric bass and she does, too—maybe that’s why I like her.

John Bazz from the Blasters is an old friend and contemporary, but every time I see him play, I want to be him. He simplygets it. He finds new ways to say something in rock ’n’ roll or roots music that may have already been said. I don’t know any other bass player who has broken two strings in a night playing with his fingers and mounted a bottle opener on his P bass.

Photo by Bob Hakins

Kirk Fletcher on Chris Cain

Photo by Jonathan Ellis

I saw Chris the first time when I was 19 at B.B. King’s Blues Club in Universal City. I played in the opening band, and I remember him being so nice and paying me a compliment. I had no idea what I was about to witness. Chris took the stage and my life was never the same again. I was heavily into Larry Carlton and Robben Ford, as well as B.B. King and Albert King. I viewed those as two different worlds until I heard Chris. He’s not a copy of these guys but created his own signature. I think one of the big things is his effortless fluidity and horn-like phrasing. And the sweetest bends in the business. As a performer he is just top notch. His wit and sense of humor makes you forget about this crazy world.

Photo by Linda Harvey

Kurt Vile on Dallas and Travis Good

Photo by Jo Mccaughey

Dallas is the psychedelic one, and Travis, the older one, is very traditional. A show-stopping trick is that they can grab each other’s guitars and play each other’s frets. Dallas, the more psychedelic one, is like a brother to me, if my brother was the same age and we weren’t twins. Whereas Travis is definitely like the older brother that you truly look up to because it’s just unbelievable how much soul and speed he has. He plays a Gretsch-style with the Bigsby. It just pours through them both.

They’ve backed up everyone from Neil Young to Neko Case. We’ve worked together and we plan to work together more. They are the realest things out there today. They do plenty of contemporary guitar things, but I feel like they’re just not affected or altered whatsoever by the modern age, which is what I try to do as well. So, it’s just traditional but not like retro or pastiche, either, because they’re influenced by things like punk and the Gun Club, and modern things as well. They’re influenced by their surroundings, but I feel like a lot of music is affected by computers. It’s very hard not to be. Their shows are just unbelievable to see, it’s beautiful.

I’m inspired and I’m also influenced by them. I take some things from them. Their music gives me chills, in the same way that draws you to your favorite bands and records. Whatever punches you in the gut … somewhere between the guts and the heart, or both—their music does all those things.

Leni Stern on Mike Stern, Shane Theriot, and Derek Gripper

Photo by Sandrine Lee

Shane Theriot is my favorite groove master! I love the songs he writes, the way he combines New Orleans grooves with modern lines and harmony. It’s truly unique and very guitaristic. He has a super-recognizable touch on the guitar. I know it’s him in three notes. He produced Dr. John’s last album and is also one of my favorite producers.

Derek Gripper is a nylon-string guitarist from Cape Town, South Africa. Aside from having a revolutionary approach to playing Bach—in open tunings!—he has adapted West African kora music to the guitar. Some of these songs are older than Bach! It’s a largely unknown, mesmerizingly beautiful repertoire. I have studied with him for the past two years. Check out One Night on Earth, his ninth recording.

Lzzy Hale on Rebecca and Megan Lovell of Larkin Poe

Photo by Jeremy Ryan

Photo by Alysse Gafkjen

Molly Tuttle on David Rawlings

Photo by Kaitlyn Raitz

Photo by Joey Martizen

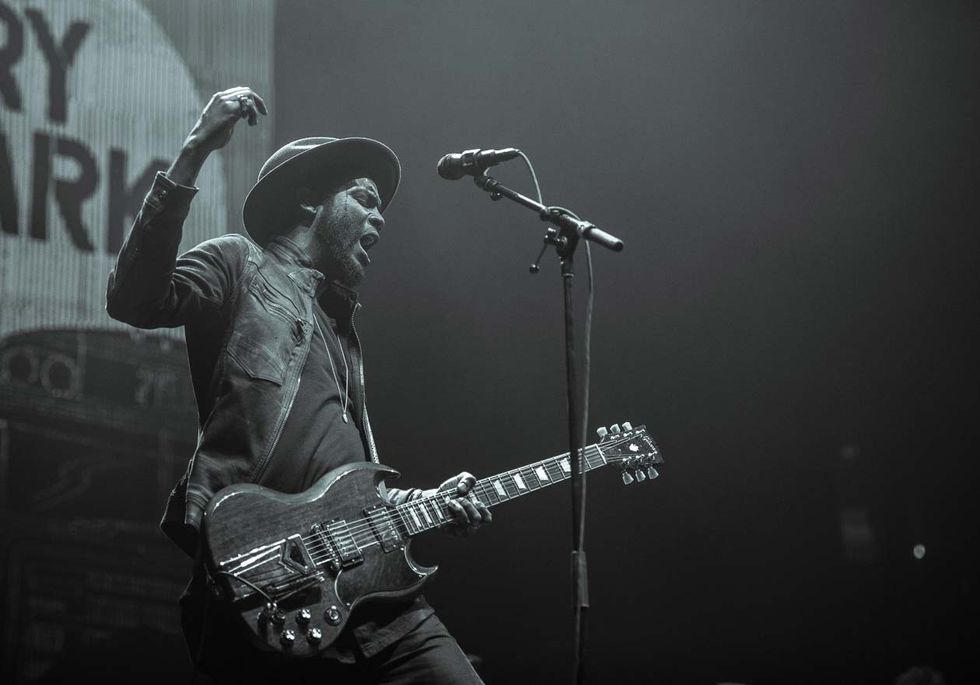

Robert Randolph on Gary Clark Jr.

Photo by Jim Arbogast

Photo by Chris Kies

Thurston Moore on James Sedwards

Jimi Hendrix breaks all the rules while having an impeccable grasp of every critical aspect of guitar playing in the instrument’s history. I use the present tense because his playing remains alive and well, and will always inform anyone looking to liberate themselves from any hint of constriction. Outliers like Derek Bailey, Keith Rowe, Glenn Branca, Lydia Lunch, Pat Place, Greg Ginn, Arto Lindsay, Lee Ranaldo, Rudolph Grey, and Masayuki Takayanagi also informed me for their resistance to critical expectations for genuine guitar skills mixed with an inherent respect for exhibition of advanced traditional technique. That balance betwixt the experimental—where the focus is sheer bloody-mindedness—and “proper” guitar playing is where I found the most sentient intrigue. Equal value could come from the Ritchie Blackmore-infused shredding of Lita Ford or the abstractions of free-jazz noise players like Sonny Sharrock, Henry Kaiser, Eugene Chadbourne, and Davey Williams.

Meanwhile, a few years ago I was introduced to James Sedwards by my sweetheart, Eva [Prinz]. She claimed a young gent on the floor just below her flat lived, breathed, and ate guitar from morning till eve. James reminded me we had first met when he and a mate snuck into the artists’ area at the 1991 Reading Festival, where Sonic Youth had played with Mudhoney, Nirvana, and Iggy Pop. James had been all of 15 years old, and he would subsequently devote attention to not only the majesty of James Patrick Page but also to noise-guitar destruction, both playful and serious. By 1998 he’d been recognized at Wembley’s National Guitarist of the Year competition, which heralded him as having, “the perfect blend of technical expertise and inventiveness,” and in 2003 he came in second place as judged by Brian May and Mr. Page himself, playing Led Zep’s “Immigrant Song” at the U.K. Riffathon guitar competition.

I knew none of this when I met the lad the second time. But when I relocated to London in 2014, James was the first musician I thought of working with. He’s a full-blown rock ’n’ roll shredder with the seemingly effortless fretboard mastery of J Mascis and Nels Cline. I asked him to employ some semblance of that lead-guitar action on a few tracks for my 2017 album, Rock n Roll Consciousness, and what transpired was mind-blowing. He would basically destroy on the very first run-through. But James isn’t looking, as far as I can tell, for guitar-hero worship. He’s looking for the glory of genuine transcendence. James’ controls are set for the future, not only on our 2019 release, Spirit Counsel, but with his Nøught project—which is an incredible display of his restless interest in high-energy shred and as good a place as any to hear his excellence.

Photo by Jan Anderson

Tommy Emmanuel on Jack Pearson

Photo by Erik Nielsen

Vinnie Moore on Randy McStine

Photo by Martin Hutch

Randy’s a real tasty and musical player and very diverse stylistically. He’s got quite a bit of technique, but always plays something that’s right for the song, with a lot of vibe that is harmonically interesting. He’s really good with subtleties like micro bends, dynamics, and little nuances such as sliding into notes à la Jeff Beck. Randy’s ideas are interesting, and he’s got some great original material on his releases. He also fronts a three-piece band called the Fringe, as guitarist and lead vocalist, and does a lot of solo gigs playing acoustic guitar and singing. There are a lot of videos online where you can hear him doing experimental stuff with acoustic guitar that’s manipulated in unusual ways with reverb and noise, as well as looping. I like his touch and tone a lot, and I would definitely recommend checking him out online or, even better, live.

Photo by Shannon Kringen

Wayne Kramer on Jeff Beck

Photo by Jeff Brinn

Beck was pushing the limits of traditional guitar playing more than any rock musician I’d ever heard up to that time. He held the key to open the door to where the electric guitar was going for me. His technical ability was head-and-shoulders above anyone else—and still is. The record Having a Rave Up with the Yardbirds revealed a future full of new music played by new musicians for a new audience, and I wanted some of it.

The MC5 was deeply influenced by this record and together we learned almost every song. The “rave up” parts were my favorite. When the band would turn the tempo over and play in double time while ignoring the key structure and just playing the guitar as a noisemaker. It was the sound of liberation. Beck prepped me for free jazz. Finally! I knew where I was going with my music. It’s a fact that music imprints on a young person’s brain during puberty in a way that is completely different from the rest of your life. The combination of raging hormones and a lust for life drilled these records into my very soul. They put me on a path that, with a few exceptions, has given me the most amazing life in music. I am doubly blessed to have lived during this period in history and still have the excitement for music I had then. It’s 61 years later and Having a Rave Up still gives me goosebumps.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)