“I grew up listening to all music, and that’s where my playing came from—country, rock, blues, and the gospel feel,” explains Herman Hitson. These varied yet inextricably linked influences probably explain why it’s hard to pigeonhole Hitson’s guitar playing, which is often described as some magical combination of funk, blues, and psychedelic rock. However, “soul,” or perhaps even “spiritual,” might be more apt, especially when considering his own assessment. “I look at my guitar playing as part of my soul—what’s coming out of me. It takes a person a long time to find themselves, because we come up mimicking everybody else, and after years and years, you’ve got to find yourself.”

Musically speaking, Hitson arguably found himself decades ago. It’s just taken the rest of the world 50-plus years to catch up.

Hitson might be the most consequential, influential guitarist you’ve never heard of—even though it’s quite possible you’ve actually already heard him. For example, the 1966 song “Free Spirit,” which was released in 1980 as the title track of a posthumous Jimi Hendrix album, is most likely Hitson. It’s one of many instances that seem to epitomize the kind of career oversights and near misses that are all too common for many underserved and exploited Black blues masters of the 20th Century. His backstory also includes a near fatal heroin addiction, run-ins with the law under the suspicion of murder, and even working as a snake-clearer in the sugar cane fields of South Florida, armed with a flamethrower.

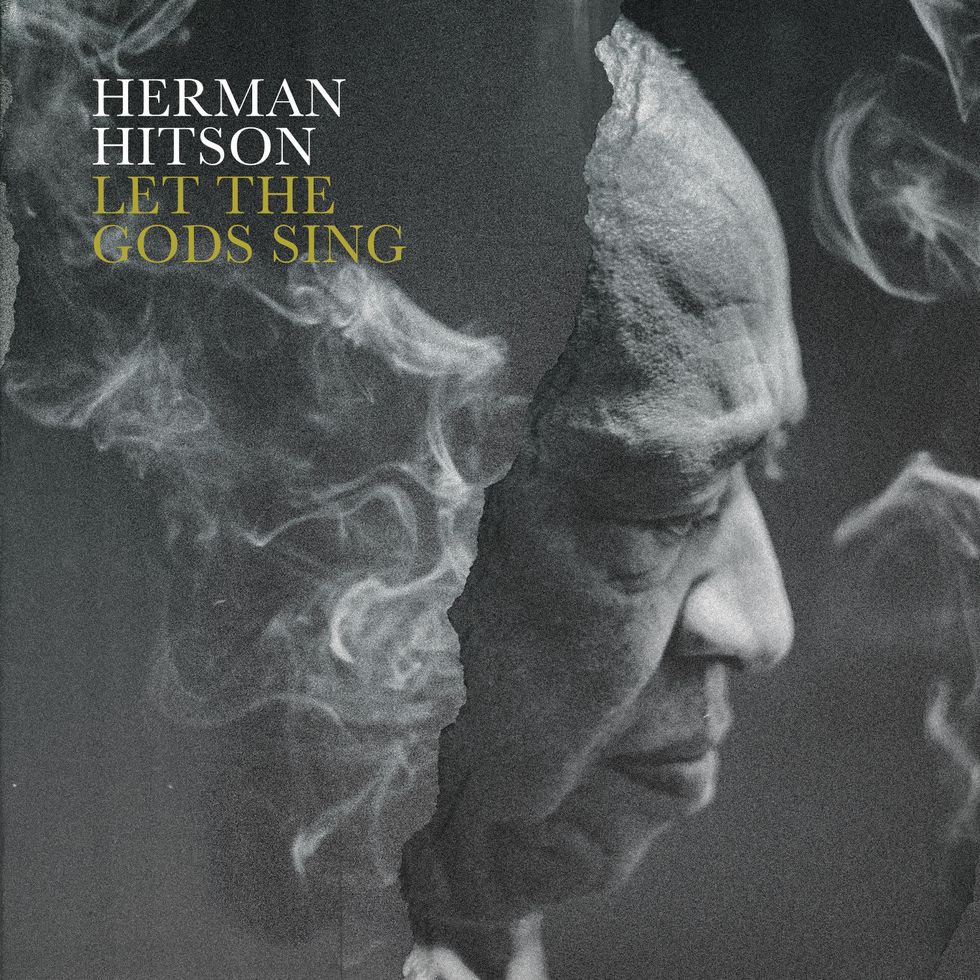

Herman Hitson - Let The Gods Sing (Official Music Video)

Though his musical career often ran parallel to, and intersected with, his more famous contemporaries—like James Brown, Jimi Hendrix, and B.B. King—Hitson’s path was not quite as linear in terms of success, or even acknowledgment. The myth, heartbreak, and redemption that appears to define his life story is countered by the tangible fact that Hitson is truly a bona fide, gunslinging guitar player of the highest order, channeling an innermost connection to the divine through his chosen instrument in ways the rest of us often only ever dream of doing. Simply put, as a blues musician, Hitson walks the talk. He doesn’t appear motivated by fame and fortune, but rather a seemingly innate desire to connect with God through music. He is what his producer/guitarist Will Sexton calls “a cosmic communicator and wah-wah guitar whisperer.”

Recently, Big Legal Mess released Hitson’s latest album, Let the Gods Sing. Produced by Bruce Watson and Will Sexton at Delta-Sonic Sound in Memphis, Tennessee, Let the Gods Sing captures the adventurous, musical spirit of Hitson, whose eclectic mix of funk, rhythm & blues, and soul is elevated by righteous grooves drenched in wah-infused psychedelia. The otherworldliness of the album lies in Hitson’s musicality—always inspired and seemingly off-the-cuff, his guitar performances resonate like sermons channeling some higher power. Let the Gods Sing features new versions of Hitson’s back catalog, including songs like the funky, frenetic “Ain’t No Other Way,” “Bad Girl”(originally recorded in ’68 and written by his longtime bandmate, singer/guitarist Lee Moses), and the Hendrix-attributed “Suspicious!”

“My guitar playing was improving real good, man, because I was working regular. And that’s when I met this little fella, Jimi, you know Jimi Hendrix, and we’d sit down and play together and learn different licks and stuff like that.”

On these new iterations, Hitson’s wah-heavy solos are melodic and lyrical, filled with the kind of emotion that can only be derived from lived experience, not just technical expertise. And though he’s clearly the bandleader, the songs have a great ensemble feel to them, indicating that Hitson’s ambition to connect is not only spiritual, but interpersonal, too.

Hitson was born in 1943, in Philadelphia, but grew up in Ocilla, South Georgia, at a time and in a place when there really was no such thing as Black radio, he says. “All I could hear was country and some Black gospel.” Interestingly, Hitson was a singer before he was a guitarist, which may account for his lyrical sense of phrasing on the guitar. A move to Jacksonville, Florida, paved the way to singing. It was there that he first joined the doo-wop group the Stereophonics and began to get a taste of traveling regionally as a working professional. Eventually, the Stereophonics hired a guitarist, who first inspired Hitson to pick up the instrument, but he says he was primarily influenced in those days by the Black blues players who sat by the front doors of barbecue joints and bars in Jacksonville, “just playing the blues,” he recalls. He maintains he was still only about 15 years old at the time.

Let the Gods Sing was produced by Bruce Watson and Will Sexton at Delta-Sonic Sound in Memphis, Tennessee. It features newly recorded versions of songs that have been in Hitson’s repertoire for decades.

Though he learned a lot from his experience with the Stereophonics, he regrettably never got to record anything with them, so when the opportunity to go on tour presented itself, he jumped at the chance. “I had never did that, man,” he says of touring. “I had played around Florida, and a few places in Georgia, so I left, and ended up in Atlanta—that was about ’60, ’63.” Hitson says that arriving in Atlanta in the early ’60s was like visiting Las Vegas for the first time. “Only this was all Black,” he remembers. “The clothing stores, the banks, and the Royal Peacock, where I could hear this guy singing, coming out of the windows, I can hear the voice, I recognize it, and it was Major Lance, and he was singing ‘Monkey Time.’”

Newly influenced by his surroundings, and the musical likes of the Tams and Jackie Wilson, coming to Atlanta was clearly a pivotal venture for Hitson. “All these guys I wanted to meet [when he was still living in Jacksonville], they was coming to my dressing room to meet me. I’d be walking down Auburn Avenue, and you might run into Sam Cooke, Gorgeous George, Wilson Pickett—everybody, man.” Eventually, he says he was approached by Arthur Collins’ manager. “He came to me and asked me, would I like to be recorded,” he recalls. “And I said, ‘Of course,’ because I had never recorded before, you see? So, he asked me did I have at least two songs that we can do, and I told him yes, but I didn’t [laughter]. I wasn’t gonna tell him I didn’t have no song [laughter].” What Hitson did have was a letter he’d written to his wife back in Jacksonville. And so he used those words for what became “Been So Long,” a crooning, soulful ballad credited to Hermon and the Rocking Tonics that garnered Hitson his first fleeting taste of popularity.

Herman Hitson's Gear

Herman Hitson names every guitar he plays "Sweet Rose." Here he's playing a Tele at the 2018 Bob Sykes BBQ & Blues Festival in Bessemer, Alabama.

Photo by Roger Stephenson

Effects

- Dunlop GCB95 Cry Baby Wah

- EMT 240 Gold Plate Reverb

Strings

- D’Addario EXL110 Nickel (.010–.046)

Because this was during the era of singles and 45s, these vinyl discs included an A and a B side. For “Been So Long,” the B side was a tune called “Georgia Grind” that “sounded like James Brown somewhat,” he sheepishly admits. “I didn’t know my record was playing nowhere, really, until I began to get fan mail, and many people really thought that was James.” And so, when Hitson was booked in Augusta, Georgia, James Brown’s hometown, the Godfather of Soul paid him a visit. “I always called him Mr. Brown, ’cause he never called me Herman, he always called me Mr. Hitson,” says Hitson. “He came to me and said, ‘Look brother, there ain’t but one James Brown [laughter].’ We became good friends, man.”

By the time this first encounter with Brown took place, Hitson’s guitar prowess had also begun pricking up ears on the Chitlin’ Circuit, a collection of performance venues throughout the Eastern, Southern, and upper Midwest areas of the United States that provided commercial and cultural acceptance for African-American musicians, comedians, and other entertainers during the era of racial segregation in the United States through the 1960s. “My guitar playing was improving real good, man, because I was working regular,” he says. “And [that’s when] I met this little fella, Jimi, you know Jimi Hendrix, and we’d sit down and play together and learn different licks and stuff like that. And so, that’s how it’s been with me and my guitar, Sweet Rose.”

“Sometimes you can hear the note and you can see colors that don’t have no names.”

Though Hitson refers to his guitar as “Sweet Rose,” it isn’t any one specific instrument, but rather the name that he bestows upon all his axes. “My name was ‘Sweet Rose’ at first—people called me ‘Sweet Rose’ with the ladies,” he explains. “I grew up and got out of that, but I used that same name for my first record label [Sweet Rose Express Records]. After that, I named my guitar Sweet Rose. The first one was a Guild. This was in ’69. Semi-hollowbody. It was a good guitar; I really miss it. The guitar that come in after that was also the same name. They all had the same name, like all of B.B. King’s guitars are going to be Lucille. Me and B.B. King talked about that. He said, ‘I got one woman, and her name is Lucille. I don’t need to name the guitars any other name.’” Throughout his career, Hitson has played Gibson, Fender, Guild, and Gretsch. “I had plenty of guitars and they all named Sweet Rose,” he chuckles.

As for Hendrix and the “Free Spirit” debacle, Hitson says “they,” likely referring to record company execs and/or radio personalities, always associated his playing with Jimi’s. “They put Jimi’s name on some of my stuff,” he says. “The thing is, they did that stuff. And they kept that stuff hid somewhere. I didn’t know where it was—I had forgotten about it. I would think about it sometimes, but then I found that them cats had put that out and put my name on the back, and under some of the songs, it had Jimi’s name—Jimi was my friend.” During their time together on the Chitlin’ Circuit, where they first met, Hitson says he’d sit all night in the hotel with Hendrix, just playing and talking. “I was telling him, man, he could sing. He always said, ‘Man I can’t sing.’ I said, ‘You can sing. If you think you have to sing like Jackie Wilson, well, you got a problem [laughter].’ I said, ‘If you sing like you, people are gonna love you.’ He was great dude, man. I really miss him.”

Herman Hitson in the studio with producers Will Sexton (middle) and Bruce Watson (right).

Photo by Tim Duffy

Let the Gods Sing features newly recorded versions of songs that have been in Hitson’s repertoire for decades. For example, he originally recorded the title song around ’66 or so. Perhaps the most illuminating takeaway from the title is that it alludes to Hitson’s spiritual beliefs, which directly inform his approach to the guitar. “I see God in music,” he explains. “I see God in music because music will give you comfort. It will relax you. It will put you in different moods. I look at the music the same way people look at the prophets. The prophets got 12 disciples. And so, in music it’s 12 notes: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, and then the sharps and flats.”

For Hitson, there’s also a connection between music and the biblical struggle of the 40 years in the wilderness. The story is a reference to the plight of the Israelites and their search for the promised land. Hitson, who converted to Islam in 1971, looks at his relationship with the guitar similarly. “That’s why I don’t never take all—what you call—errors, out,” he says. “I leave something in there to show the struggle. So, that’s the way that is, man—pain and expression. It’s a spiritual thing. If you’re talking about a religion, that’s what I do religiously—music.” One could argue that creationism is essentially at the heart of Hitson’s spiritual and musical perspectives. “I look at God in everything in the creation,” he explains. “How the wind blows the trees—you can see the trees dancing. This is where I see God. But you can’t see God—you can [only] see spirit in people. So, the spirit of God, that’s what I look at. And so, that’s how I play, and that’s how I see music. Sometimes you can hear the note and you can see colors that don’t have no names.”

“I look at my guitar playing as part of my soul—what’s coming out of me. It takes a person a long time to find themselves.”

The music, and magic, of Let the Gods Sing is further elevated by the fact that the album was recorded old school, as in live, in just two days, and deftly performed by a backing band (dubbed the Sound Section by Watson) consisting of Will Sexton (guitar), Mark Edgar Stuart (bass), Will McCarley (drums), Art Edmaiston (horns), Al Gamble (organ), and Marcella Simien (vocals/guitar).

“Those guys were pros,” says Hitson. “So, it was easy for me to play with them. We can look at each other and we can tell where we’re going from there.” It was the first time Hitson recorded with an all-white band. Previously, “It was always all Black, or it was integrated,” he says. Most of the tunes, having been previously recorded, were sent to the musicians in advance. “It didn’t take long because everything was easy to follow, and the spirit was there, man. When the spirit is in there, everything is made comfortable, and it’s easy to think, with no distraction. And so, everybody just played their butts off.” Recently, Hitson became part of the Music Maker Foundation, an organization led by Tim Duffy committed to supporting carriers of America’s oldest roots music traditions. “I really feel good about it,” Hitson says of the relationship. “I’m very glad that they chose me, and I’m hoping this album here can bring me back into where I need to be.”

Hermon Hitson - Hot trigger

Herman Hitson lets his wah-wah do the talking on his song “Hot Trigger,” which has sometimes been attributed to Jim Hendrix. It’s easy to hear a relationship between this song and Hendrix’s “Pali Gap,” perhaps reflecting their friendship and occasional late-night jams.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)