In 1997, Mark O'Connor faced every guitarist's worst fear. He was teaching at his O'Connor Method String Camp that summer when he developed a debilitating case of bursitis in his right elbow. "Doctor's advice was that I limit or discontinue some of the activity that caused the bursitis, as the condition wasn't going to disappear entirely," O'Connor explains. As a multi-instrumentalist with a high-level violin career, he had a choice to make. "I sacrificed the guitar and mandolin to preserve my violin playing. I was very sad to see it go, but I needed to preserve my ability to play the violin, because it was the thrust of my career."

By that time, O'Connor had taken violin playing to groundbreaking new places. He'd released a string of solo records on major labels, including 1991's The New Nashville Cats, which took stock of the contemporary Nashville session scene by featuring more than 50 collaborators. His new trio with Yo-Yo Ma and Edgar Meyer had released their much-lauded debut record, Appalachia Waltz, in 1996, and he'd recently composed and recorded a violin concerto, a string quartet, and a soundtrack for the PBS series Liberty!, which featured Yo-Yo Ma, James Taylor, and Wynton Marsalis.

"It became too much about technique and not as much about what drew me to the guitar in the first place, which was its beautiful sound."

As far as career ambitions go, O'Connor's violin playing overshadowed his guitar playing, but his early accomplishments on 6-strings were also extraordinary. O'Connor started early, studying classical guitar starting at age 6 and soon moving into flamenco. He took on classical violin as a way to perform more recitals, and it was his interest in violin that helped him discover bluegrass. He explains, "I heard the fiddle on the Johnny Cash show, and it was the fiddle and fiddling I got into that led me into bluegrass guitar. I would've never known that existed in my surroundings in Seattle, if it weren't for the fiddle."

Once O'Connor fell in love with bluegrass, things started happening quickly. By age 11, he'd stopped playing classical and flamenco guitar and focused solely on flatpicking. "When I got into bluegrass and started with a flat pick, for me, that was rock 'n' roll rebellion. I was going down this path and there was no return," he says. And he soon began winning bluegrass guitar competitions, including the National Guitar Flat-Picking Championships.

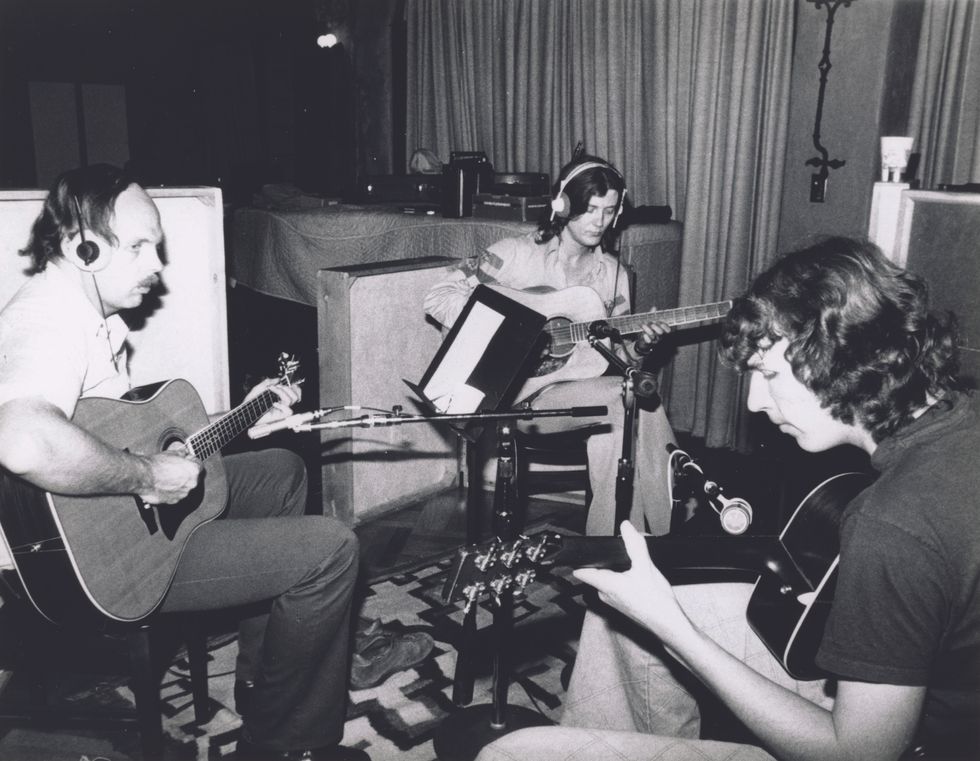

Surrounded by his inspirations Tony Rice (center) and Dan Crary (left), O'Conner cuts "Fluid Drive" for the first Markology album, in 1978. Flatpicking doesn't get any finer.

At 13, O'Connor met Tony Rice, and by the time he'd turned 15, the elder guitarist had taken him under wing. When O'Connor recorded his landmark album, Markology, in 1978, Rice played alongside the 16-year-old and helped him mix it as well. Markology was a remarkable feat that found the young prodigy holding his own amongst elders like Rice, David Grisman, and Sam Bush. It was the first recorded evidence that he'd aligned himself with the jazz-inspired ways of his collaborators and was creating his own original and imaginative voice in bluegrass, setting the world on fire with his 1945 Herringbone Martin D-28. Two years later, at only 18, he stepped into his mentor's shoes, replacing Rice in the David Grisman Quintet for their Quintet '80 album.

O'Connor's guitar and fiddle playing co-existed on equal footing for quite a while. "Throughout my childhood, it was neck and neck," he says. "The distinctions could include that there were more big fiddle contests than big guitar contests, so I found myself going to three times as many major fiddle championships. That would automatically suggest that I'm spending more time on that instrument." When he joined the Dregs, playing violin on 1982's Industry Standard, Steve Morse insisted that O'Connor play both instruments in concert, though he began to notice how hard it was becoming to maintain his technique on both, and notes, "It was just so hard to keep up everything, especially with the kind of touring that we were doing, it was just nonstop."

Mark O'Connor's Gear

On Mondays this year, Mark O'Connor and Maggie, his wife, have been livestreaming concerts from their home. She is part of the Mark O'Connor Band, which includes his son Forrest and daughter-in-law Kate Lee.

Strings & Picks

- BlueChip CT55

- D'Addario EJ18 Phosphor Bronze (.014–.059)

It wasn't long before Chet Atkins encouraged him to move to Nashville at the age of 22, imagining he'd find a career as a session guitarist, that O'Connor committed to the violin as his principal instrument. He explains, "I found myself on a Glen Campbell album playing guitar, mostly, and doing an occasional fiddle solo. Something just clicked in my mind where I thought, 'There's so many guitar players in Nashville and there's hardly any fiddle going on.' That was 1983, '84. I just took it upon myself to be the person that brought back fiddling into country music, and I became known as the top fiddler."

He quickly began playing top-tier sessions as well as making a string of major label records under his own name, and his guitar playing took on a more background role. By the time he suffered his injury in 1997, he admits, "I was kind of a little bit burnt out about it. Maybe that's what led to my injuries. Sometimes when you're not completely focused on what you're doing, that's the time that you get injured. I was going through the motions a little bit and maybe over-practicing, trying to overachieve, pushing myself maybe for the wrong reasons. It became too much about technique and not as much about what drew me to the guitar in the first place, which was its beautiful sound."

"Music is a gift, I think, to us all."

Setting aside his guitar and mandolin, O'Connor found that he could continue playing violin, and for the next two decades fiddling took over his musical life completely. He didn't touch a guitar. "I never thought I would play guitar again, and I had grown accustomed to that fact. I had other bouts of bursitis in both my hip and my knee since then, so I knew I was prone to it. I just never wanted to take the chance," he says.

In 2017—20 years after his injury—he was busy focusing on his Mark O'Connor Band, with his wife Maggie on violin and vocals, his son Forrest on mandolin, guitar, and vocals, and his daughter-in-law Kate Lee on violin and vocals. While reminiscing about his multi-instrumentalist past, his family encouraged him to give the guitar another try. "I was wondering how I could add some variety to the instrumentation for our group," O'Connor says. "My family was encouraging me to try the guitars out, maybe play some easy-going strums on one of our songs, and, carefully, I started to try out some guitar stuff."

In his early years as a bluegrass fiddle trailblazer, O'Connor, at left, performs at a festival with (left to right) Eddie Adcock on banjo, Peter Rowan on guitar, and Jerry Douglas on dobro.

Photo by Jordi Vidal

As he began testing his limits, O'Connor realized that he could do a lot more than strum some chords, and one thing soon led to another. "It was not too long before I began to take a lead line on one of the easy songs on stage," he says. "That led to my taking my old Herringbone off the wall back home and experimenting. Over two or three months, I started building up calluses, and as soon as I got my calluses, then my right hand seemed to start to coordinate a lot better. The strumming came back pretty quickly. It was just coordinating mainly crosspicking and lead stuff. And when that started coming back, the whole thing just opened up and I was inspired."

It's hard to imagine the thrill of revisiting the guitar after such a long hiatus. O'Connor describes the feeling: "It felt like a gift. All of a sudden it just felt like it was meant to be—that it was my time to play the guitar again. Music is a gift, I think, to us all. I thought about Tony right away. His sound was in my mind the whole time, and his tone, the way he projected on the guitar, the way he held the guitar and the physicality of it."

"The strumming came back pretty quickly. It was just coordinating mainly crosspicking and lead stuff. And when that started coming back, the whole thing just opened up and I was inspired."

O'Connor decided to document his progress on the guitar, creating arrangements of tunes and recording them once they were ready. "It dawned on me that I had been storing up guitar ideas this whole time, and maybe they were held in my subconscious all along, never having an outlet for them, and then they were kind of spilling out onto the guitar."

Those recordings slowly coalesced into Markology II, a title that suggests not only a sequel to his debut album, but also a renewal or rebirth of his relationship with the instrument. Much like on his debut, Markology II once again shows that O'Connor possesses one of the most unique and versatile voices in modern acoustic guitar playing. Like his fiddle playing, his approach to the guitar now transcends the more bluegrass-focused playing of his youth, and he shows off a versatility and virtuosity that is stunning.

The strings O'Connor had on his Martin D-45 when he put it aside 20 years ago were still on the guitar when he recorded the first two songs for his new album. Nonetheless, "On Top of the World" and "Ease With the Breeze" ring with beauty and precision.

From "On Top of the World" and "Ease With the Breeze"—the first tracks recorded for Markology II, using his D-28 with the same strings that had been on it since he put it down in 1997—to awe-inspiring, fleet-fingered arrangements of "Beaumont Rag" and "Salt Creek," O'Connor proves that not only has he not lost anything with regards to his technique and musicality, but he's continued to grow well beyond the already highly developed playing we last heard from his flat-top box in the '90s. This makes Markology II not only a unique entry in his large discography, but a unique entry into the canon of solo acoustic guitar records that demand close study.

While he once again plays with rare speed and dexterity, O'Connor brings a lot of awareness to his physical approach to guitar. At 59, he knows he has to take care, listen to his body, and follow its cues in order to avoid another injury. "I have a template of how to approach playing with injury now," he assures. "The main thing is that you have to just discontinue playing the moment you feel pain in the arm or hand area. I mean, literally, as soon as you feel the twinge of pain for 5 seconds, you have to discontinue. I'm very hyper-aware of my limitations in that way." With this thoughtful and focused awareness, it will be thrilling to hear where Mark O'Connor takes his guitar playing for years to come.

Alabama Jubilee | Mark O'Connor | "Markology II" (Official Video)

Mark O'Connor takes a relaxed and efficient approach to picking while he sets his JC Baxendale-built dreadnought on fire with this version of "Alabama Jubilee." His creative and melodic solo guitar arrangement leaves lots of space for clever chording and hyper-fast licks while maintaining a casual and airy feel.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)