Nancy Wilson is a bona-fide rock legend. From founding classic-rock giants Heart—alongside her sister, Ann Wilson—to four Grammy nominations, being inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 2013, and scoring films, this 6-stringer has had a legendary career. And now she is releasing her first solo album, You and Me.

Since the 1970s, Heart has been one of the most respected rock bands of all time. With hits like "Barracuda," "Magic Man," and "Crazy on You," the group showed what a pair of rock 'n' roll sisters from Seattle could do, and laid the foundation for a career spanning more than half a century.

Though the band was riding high throughout the '70s, times changed in the '80s. It became all about L.A. glitz, glamour, and hairspray. Unlike many of their contemporaries, Heart embraced the new era, reaching even higher levels of success. But it didn't come without a cost, leaving the sisters longing for home as the decade came to a close.

Nancy Wilson "Daughter" OFFICIAL MUSIC VIDEO

Nancy covers the Pearl Jam hit "Daughter."

"At the end of the '80s, it was kind of done for us," Wilson says. "It was such a different kind of era that we came from. Because of MTV, because of all the image-making and all of the glam and costumery, the corporateness of it all, we felt out of place. Even though we were bigger than ever!"

Ready for something different, the Wilson sisters headed back to the Pacific Northwest for a fresh start. Little did they know, it turned out to be perfect timing. Bands like Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, and Alice in Chains were moments away from changing the world.

"The minute you heard 'Smells Like Teen Spirit,' it was all over for the '80s. It was cooked," says Wilson. "So, we went back to Seattle. We just threw it all away after the '80s. No manager, no record company. We started another kind of new experimental band called the Lovemongers. We just went out and played clubs on our own.

"The songs are a variety of things I can do. The fingerstyle acoustic and the more personal, confessional poetic thing is one of them. And I love to do the rock thing, too."

"But the guys from the Seattle explosion, all the guys from Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, and Nirvana, were really appreciative and supportive of the history, of how we got there, and the fact that we'd kind of thrown up our hands and were kind of poo-pooing the rest of the '80s corporateness. They were right there for us on that."

Since that time, Wilson has stayed plenty busy. Heart has continued to record and tour, she released albums with the Lovemongers and her side project Roadcase Royale. She also built a celebrated film career, composing music for Vanilla Sky, Almost Famous, and Jerry Maguire. Through it all, her musical community remains a vital part of her career, helping shape You and Me, her first solo studio release.

Wilson has always preferred raw emotion and the power of great songs translated through her guitars. Fans of her previous work will be glad to hear that hasn't changed. You and Me includes raw rockers like "Party at the Angel Ballroom," the dark and heart-wrenching "The Dragon," and even a fingerstyle acoustic tribute to Eddie Van Halen ("4 Edward"). Best of all, each song is filled with gorgeous guitar tones and perfectly executed performances.

But just because the album sounds familiar doesn't mean Wilson is afraid to take chances. For instance, while most rock albums charge out of the gate, You and Me opens with its deeply personal title track, a meditative conversation with her late mother, taking you by surprise and instantly drawing you in. "It's pretty brave to start an album with something that intimate," admits Wilson. "But I thought it would be deceptively simple for the first track. It's really interior. It's a conversation with someone in zero gravity."

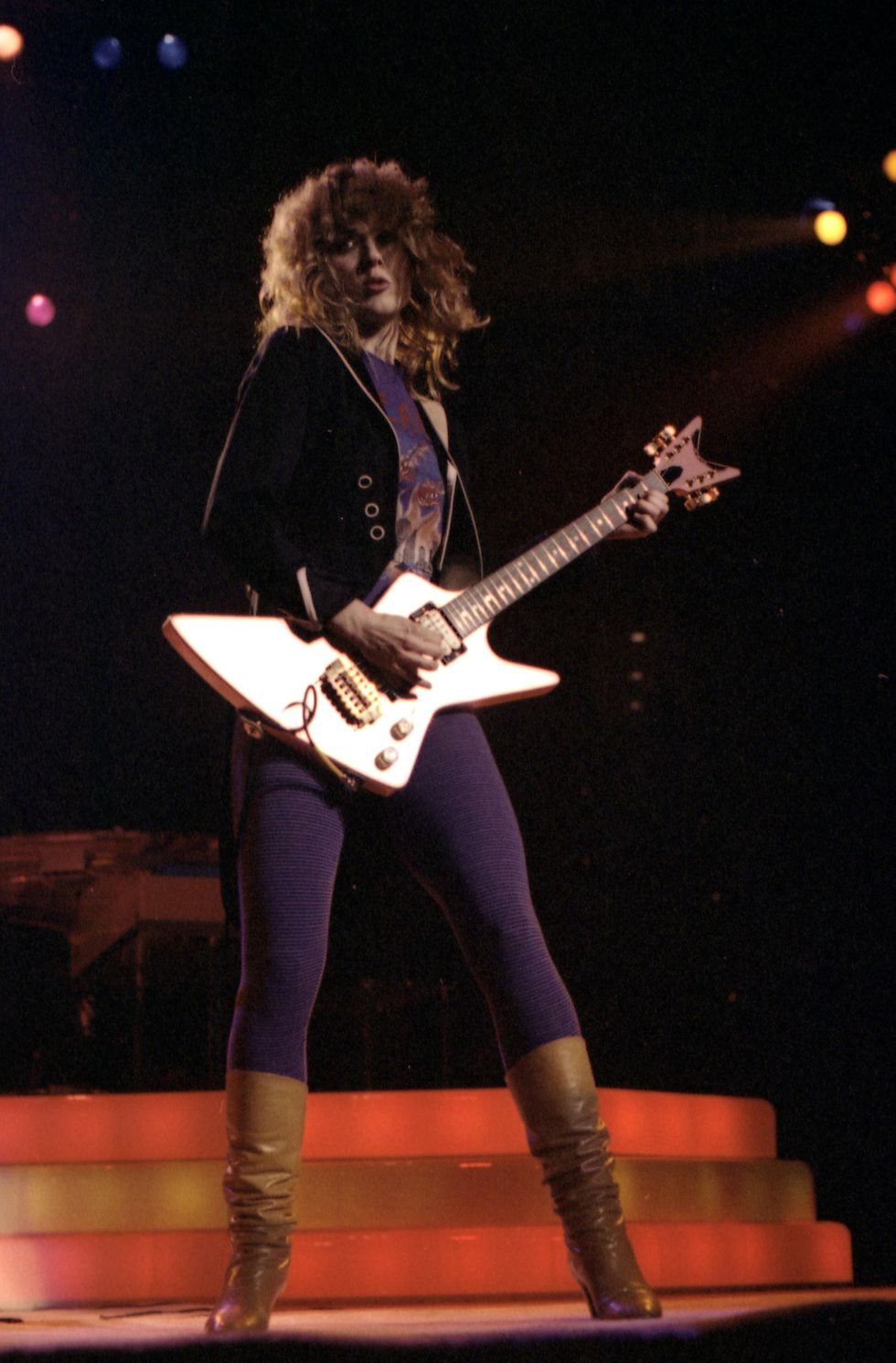

Nancy Wilson rocks a pink Baby Dean Z onstage with Heart in Dallas, Texas, circa 1982.

Photo by Stuart Taylor/Frank White Photo Agency

Wilson's fans have been waiting on a solo album like this for decades. So why now? With COVID lockdowns, travel restrictions, and the movie industry on hold, Wilson was going stir crazy. She had to create. "It was about trying to get back to writing in general," Wilson says. "So the songs are a variety of things I can do. The fingerstyle acoustic and the more personal, confessional poetic thing is one of them. And I love to do the rock thing, too."

With its wide breadth of styles, You and Me is very much a musical scrapbook, filled with new compositions, timely resurrections of older material, and covers of some of her favorite songs. "In a way, the variety on this album is a lot like a Heart album," Wilson offers. "You traverse all these stylistic statements and stories you want to tell. But it still fits together somehow."

Lockdowns and travel restrictions forced Wilson to take a different approach when creating the album. That meant swapping files online as musicians tracked their parts on their own. Wanting things to go as smoothly as possible, Wilson reached out to her extended musical family and enlisted the help of some very familiar faces.

"With acoustic, my sister and I used to do a lot of duet performances. I had to learn how to be the band by myself. I would pound on it, and put bass lines in, and do heavy rhythm stuff. I would even put in the occasional almost lead part through the rhythm part."

"Because of the shutdown, the players were mainly from the last Heart tour, and Ben Smith, who was in Heart forever before that," Wilson says. "They're all in Seattle. So, I started songs on my own and sent them to my guy in Denver [engineer Matt Sabin], who put it in Dropbox for all the Seattle guys. Then they made the rounds with the track."

With such an impersonal approach to recording, it can be tough to capture the energy and spontaneity that rock requires. But thanks to her familiar cast, You and Me is an exception. Old-school rockers like "The Inbetween" and "The Rising" sound like a well-oiled band playing a few feet from each other.

"It's shocking when I hear it now. It's such a tight-knit group of players that we're dying to play together. But we just had to do our best without being in the same room," Wilson says. "But we're so familiar with each other's way of playing that it's second nature."

Wilson and her bandmates didn't go it alone. They had help from some of the A-list friends Wilson made throughout her career. Sammy Hagar lends his voice to a cover of Simon & Garfunkel's "The Boxer," Roadcase Royale bandmate Liv Warfield sings on the Cranberries' "Dreams," and Taylor Hawkins (Foo Fighters) and Duff McKagan (Guns N' Roses) give "Party at the Angel Ballroom" its unmistakable energy.

Nancy Wilson's Gear

"I usually use my Epiphone more live than on this album, because I have a couple of those classic pieces," says Nancy Wilson, referring to her signature Epiphone Fanatic, shown here, and the '63 Tele and '60s SG Custom Junior she uses in the studio

Photo by Ken Settle

Guitars

- 1963 Fender Telecaster

- 1960s Gibson SG Junior

- Epiphone Nancy Wilson Signature Fanatic

- Martin HD-35 Nancy Wilson Dreadnought

- Libra Sunrise acoustic

Strings and Picks

- Dunlop Tortex medium/heavy

- Ernie Ball Slinky mediums

Amps

1960s Fender Deluxe

Orange Tiny Terror

Effects

- Vintage Electro-Harmonix Memory Man

- Way Huge Swollen Pickle

"I knew that I wanted to get Sammy to join in on something, because I've played a bunch with him in various situations. He came out for our Christmas show in Seattle, and I did a couple of songs with him. With Taylor, we did a few talk shows and various benefits. And same with Duff.

"Taylor actually asked me first. He was making his solo album recently, called Get the Money. He said, 'Would you come sing on my album?' And I said, 'Of course, I will! I'll drive over.' Then I was like, 'Well, I'm going to make an album now, so what do you have laying around? Do you have a jam or anything?' And he said, 'As a matter of fact, I've got this thing right here that Duff and I jammed on.' I cut it up and put it into a song and sang it. Then I sent it back to Taylor, and he put a whole bunch of, as he would say, 'rad vocals, man.'"

You can hear the joy that Wilson's guests brought to You and Me. But sadly, many of Wilson's Seattle-based friends and collaborators also share in tragedy. Through the years, they have said goodbye to such rock luminaries and friends as Andrew Wood, Mike Starr, Kurt Cobain, Layne Staley, and Chris Cornell. Wilson translates that hurt beautifully on the album's most striking song, "The Dragon." Written before Staley's death, it's a brooding plea and tribute to the former Alice in Chains frontman.

"Everyone could see clear as day that he was struggling so hard with his own addiction and that it was going to take him," Wilson recalls. "That's the emotional content behind that song. It was like, 'No, don't go down there!' But we knew it was probably already too late. Then after Layne was gone, Jerry [Cantrell] kind of disappeared on everybody for a little too long. So, we invited Mike Inez to be in Heart until Jerry revived. It's really the truest of the stories about the support group, the brotherhood, and sisterhood. It's about that group of people, the musicians in the Seattle scene. There are good people there."

You and Me is Nancy Wilson's first solo studio album. It was made during the pandemic with band members in different locations, and they used Dropbox to transfer files to each other. Sammy Hagar, Duff McKagan, and Taylor Hawkins are among Wilson's collaborators on the release.

Along with its deeply personal themes, "The Dragon" is made all the more captivating by its wide breadth of guitar tones. That's true of the entire record. And though Wilson is famed for her acoustic playing, her trusty electric is responsible for a whole lot of them.

"I mostly played the '63 Tele for rhythm and some clean stuff," Wilson says. "Like on 'You and Me,' there's one other acoustic player [Bob Limbocker] that played the main part that I fell in love with. I knew that I could just add a clean electric at a certain point in the song where the clean electric doubles the acoustic."

Though she's the first to admit that she's not a gearhead, Wilson does swear by some favorite electric guitars and amps for capturing her tones. "My '63 Telecaster is the one on the album cover. I've had it forever. I also have the SG that I play, with the wang bar [1960s Gibson SG Junior]. I usually use my Epiphone [Nancy Wilson Signature Epiphone Fanatic] more live than on this album, because I have a couple of those classic pieces. There's no replacing those types of tones and really good microphones as well. Old tube mics, old tube amps, and the '63 Tele, all with the original dirt that you're going to hear in it.

"For amps, I mostly used my Fender Deluxe, an old one. I also used my Orange head and cabinet. It's the Tiny Terror. It's a great amp, and it really works!"

"The minute you heard 'Smells Like Teen Spirit,' it was all over for the '80s. It was cooked."

For her live rig, Wilson relies on a large pedalboard. But, with lessons learned from scoring films, she got the most from only a couple of her favorite pedals throughout the album. "Doing score music really informs my songwriting and my performance. It's an exercise in what to leave out. If you're writing to a picture, and there will be dialogue, you need to be sure you're not stepping on it. You have to know when to shut up, how to hover, and how to create low moments that don't have a lot of movement.

"Like, with some of my electric rhythm playing, there's a super-heavy foot pedal that I got into using. It's called the [Way Huge] Swollen Pickle. It's huge! I learned how to mute into a more open section, then use that pedal to build into a big rock moment. It's on the Cranberries song 'Dreams' and 'I'll Find You.' You don't pull all the stops out all the time. But I only used a couple of pedals. I think it was the Swollen Pickle and an old Memory Man. It creates a delay-echo kind of tonality with almost a phase thing going on. It's very old-school stuff."

Of course, you can't discuss Wilson's playing without talking about her contribution to rock acoustic guitar. In many ways, her powerful rhythms and iconic fingerstyle pieces (the intro to "Crazy on You," anyone?) elevated the instrument to equal status next to its electric sibling.

"With acoustic, my sister and I used to do a lot of duet performances," remembers Wilson. "I had to learn how to be the band by myself. I would pound on it, and put bass lines in, and do heavy rhythm stuff. I would even put in the occasional almost lead part through the rhythm part. But I always approached it almost like a percussion instrument."

This Duesenberg Starplayer has become a staple for Nancy Wilson during Heart's live shows. It belongs to her guitar tech, Jeff Ousley, and was given to him by Elvis Costello

Photo by Debi Del Grande

Wilson's trademark acoustic playing is undoubtedly the bedrock of You and Me. And it takes the lead on "4 Edward," her solo fingerstyle piece dedicated to one of the greatest guitar players of all time. The song is an emotional journey, and both a tip of the hat to some of EVH's best riffs and the friendship between him and Wilson.

"The times when we got to hang out, we were really fond of each other as friends. He was a novelty unto himself. And he recognized that, as a guitar player, I was pretty much a novelty myself. We were one-of-a-kind in our own way, and unexpected and different from everybody else. The fact he recognized that meant everything to me.

"But Eddie didn't have a real acoustic, at least on the road. So one day, I said, 'Here's one right now. You take this. If you don't have one, here's one.' The next morning, he gifted this beautiful acoustic piece through the phone into my ear. I remember it was very classical, mostly major chord structures, like most of his stuff always was. Joyful, and elated, and inspired. A little rock, of course, and then something heavenly in there. That was the thing I was trying to channel when I tried to make a tribute song for him."

Like her tried-and-true stable of electrics, Wilson tracked these acoustic performances with a surprisingly small number of guitars. "I have a signature Martin that I play on most of the acoustic stuff. Then there's another custom-built guitar that I got in 1976 from a guitar builder in Vancouver B.C. He saw me play and built me a guitar and gave it to me for free. It's called the Libra Sunrise. I said, 'I can't afford this. This is the best guitar I've ever played!' He said, 'Just call it a 100-year loan.' I sent him a good chunk of change to pay him for the guitar decades later."

Nancy Wilson "4 Edward" Storyteller Performance

Hear the story and a live performance of "4 Edward," Wilson's solo acoustic tribute to her dear friend and guitar legend, Eddie Van Halen.

With her first solo album under her belt, millions of albums sold, a highly respected career in film, and … oh yeah… having played "Stairway to Heaven" in front of Led Zeppelin at the Kennedy Center Honors ceremony, Wilson has achieved the stuff of dreams.

Yet, 2021 finds her as busy as ever. She's preparing a performance of her classic hits with the Seattle Symphony Orchestra. On top of that, there's a Heart biopic in the works directed by fellow Seattle rocker, boundary breaker, and TV star Carrie Brownstein (of Sleater-Kinney and Portlandia). With such a lauded career, you'd think Wilson has earned some time off. But that's just not her style. Whether with new music, film, or hitting the stage, Wilson must keep moving forward, keep rocking, and keep creating.

Why?

"The simple answer is sanity. It's what keeps me sane, I believe. Basically, I'm born to create stuff. The thing that's the most gratifying, the most uplifting, and the most fulfilling in my world is to be creative and make some magic where it was not there before."

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Shop Scott's Rig

Shop Scott's Rig

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Luis Munoz makes the catch.

Luis Munoz makes the catch.