“I get nervous if I have my shoes on when I am playing,” says Andy White, the guitar half of the psychedelic, krautrock-style, jam-centric duo Tonstartssbandht [pronounced: tone-starts-band]. “For some reason, playing with shoes on just feels weird.”

How weird? That’s hard to say, but playing barefoot has helped the guitarist figure out a few tricks and use it to his advantage. “I want to be able to know I have the option to do what I need to do on the fly or, at the very least, feel myself grounded,” he adds. “It all comes down to pedals at the end of the day. Even if it’s not tweaking them, but just activating them, or turning them off.”

A duality—part mystical, part practical—describes White’s musical ethos as well as the history and evolution of Tonstartssbandht, which he founded in 2008 with his older brother and drummer, Edwin. The duo’s most recent release, Petunia, marked a new phase in their development, as they eschewed fuzz and lo-fi sonics in favor of cleaner tones. Despite capturing live instrumental takes, the album is very much a studio creation. The brothers took advantage of the downtime afforded by Covid—holed up together in their hometown of Orlando—and experimented with gear, holding out for perfect takes, and even built an iso booth.

“It definitely felt alien,” White says. “It was very weird, and I’ve second-guessed myself a lot of the time. ‘Should it be taking this long? Should it sound so high fidelity? Are people going to hate us or think we sold out?’”

Tonstartssbandht - Pass Away (Official Video)

Relative to the rest of their work, Petunia sounds like it was captured with Steely Dan-like precision. Their previous effort, Sorcerer, was recorded under completely different circumstances that illustrate the brothers’ ability to embrace serendipity and circumstance. “Sorcerer was recorded at our old place, when Ed and I were both living in Brooklyn in a big, shared living and art space called Le Wallet, in Bushwick,” White says. “If you could build a vocal booth within a vocal booth, you would not be able to escape the noise, because the building was surrounded on three sides by the elevated M train. I didn’t mind sleeping there, but you would not be able to get a quiet take unless you timed it perfectly for when the M wasn’t running for five minutes or so. We knew we were working with the ambient noise of a train going by, or a roommate making dinner across the room who wants to shout or something. There was no avoiding that.”

The much more delicate sound of Petunia is a fresh entry to the band’s discography. The album opens with “Pass Away,” a dreamy, spacious, falsetto-laden jam that grows and grows, and yet never forgets it’s supposed to groove. White layers chord extensions over an ostinato bass figure that’s played with his thumb and—check it out—isn’t overdubbed. In fact, none of the guitar parts are. Even the hypnotic, uneven delays that complement the melodic, upper register double-stops on “What Has Happened” were recorded as one complete take. White was able to create a rich, detailed sonic image by carefully dialing in his amps, plus mixing.

“I’ve second-guessed myself a lot of the time. ‘Should it be taking this long? Should it sound so high fidelity? Are people going to hate us or think we sold out?’”

“I have trouble sometimes,” he says. “If I set up mics in a room and I think, ‘This sounds nice and heavy for a two-man band,’ when I listen back to the recording, I can be disappointed because it doesn’t quite capture how heavy it sounded. If I am left to my own devices to mix—like we were on our previous albums—it’s just a lot of trial and error with EQ in post. With Petunia, we had all the carefully recorded takes to work with, and that’s why we brought it to other people to mix. It took us long enough to figure out how to record it how we wanted to, and we didn’t want to fuck up what we worked on so hard by trying to mix it ourselves.” That also paid off by showcasing the haunting qualities within White’s voice, which spins warm melodies and charms in airy falsetto for most of the album, but can drop into a growling attack when it’s time to bare teeth.

White uses two solid-state Lab Series amps—he has both the L5 and L6 models—which he finds break up to his liking and cover a broad tonal range. The Lab Series is from Gibson’s Norlin era, the 1970 to 1986 period when the company was producing some of its wackiest products, including offbeat guitars like the Marauder and Corvus, and solid-state amps that featured, for the time, cutting-edge electronics designed by sister Norlin company Moog. You don’t see Lab Series amps around that often, and for White, they’re perfect. “Some guitar guys tell me they have a tube sound without the finicky-ness of tubes, and I’ve always found them to be very reliable. I try to get a nice boost-y heavy bass from the amps, and when it comes to recording it, it’s luck and trial and error.”

The brothers White: Edwin (left), drums, and Andy (right), guitar.

White runs the two amps simultaneously and bounces his signal between both—not a dry signal in one amp and wet in the other—creating a ping-pong effect and fattening the sound. You can hear that in action on Petunia, especially on songs like “All of My Children” and the aforementioned “What Has Happened,” where he also leans heavily on an Electro-Harmonix Super Pulsar.

“It uses a quarter-note tremolo really hard—like a strobe—and then one repeat 100 percent wet and dry delay on the dotted quarter,” White says. “I used to dial that in on the fly on a live show and it would take forever to get it exactly right tuning the tremolo ratio and getting the delay to hit it just at the right swing. Now I just adjust the Super Pulsar and tune it to make it exactly how I like, and then save it as a preset.”

Andy White's Gear

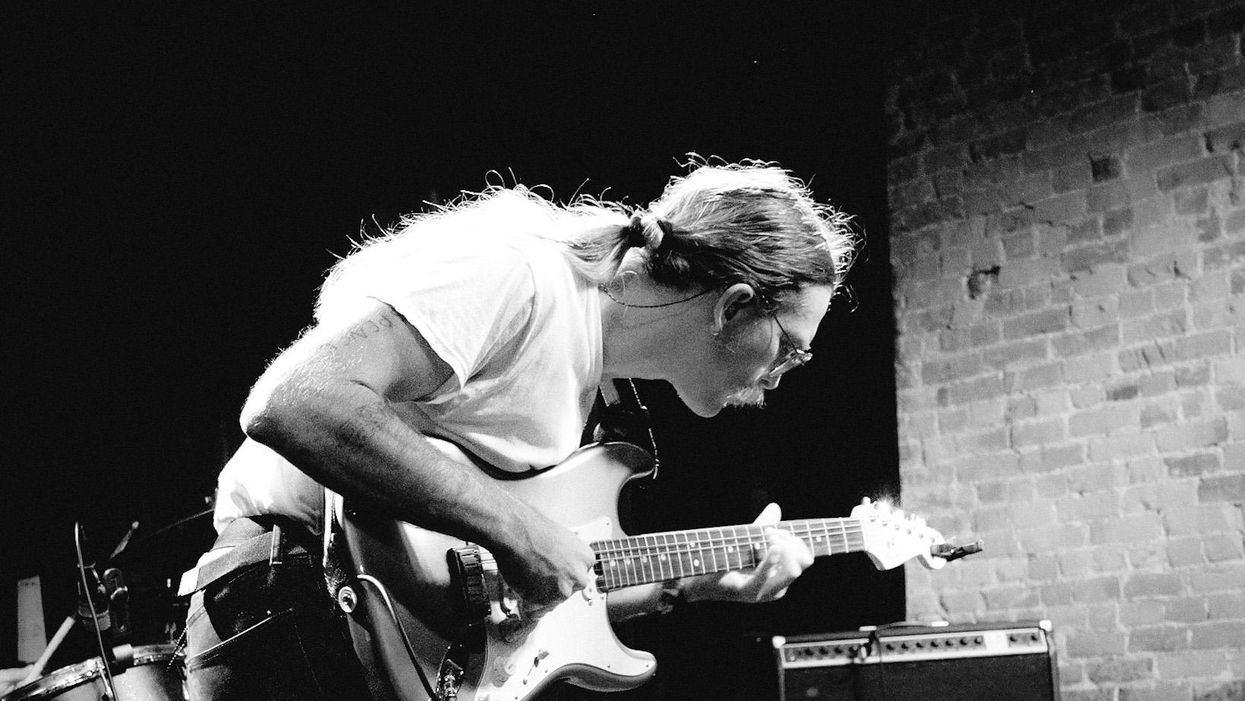

Seen here at Brooklyn’s Market Hotel, Andy White splits his Strat’s signal into two vintage Gibson Lab Series amps to achieve maximum tone density and psyched-out ping-pong effects.

Photo by Tod Seelie

Guitars

- Danelectro 12-SDC

- Early ’70s Gibson SG with Bigsby

- Fender American Elite Stratocaster

Amps

- Lab Series L5 2x12

- Lab Series L6 1x15 bass combo

Strings

- Ernie Ball Power Slinky (.011–.048, for 6-strings)

- Ernie Ball (.010 sets, for 12-string)

Effects

Boss TU-3 Chromatic Tuner

Boss GE-7 Graphic Equalizer

Boss OC-3 Super Octave

Electro-Harmonix Little Big Muff

Electro-Harmonix Super Pulsar

Electro-Harmonix Stereo Memory Man with Hazarai

DigiTech X-Series DigiDelay

Boss RV-6 Reverb

TC Helicon VoiceTone Create (for vocals only)

White’s recently developed pragmatic approach to gear applies to his guitars as well. He relies on three: an SG and a Danelectro 12-string that are tuned to D standard, plus a Strat tuned to a hybrid C# tuning of his own invention (C#–G#–C#–F#–G#–B), with its bridge stopped up with cork to disable the tremolo.

“I went to the local guitar guy in Orlando and had him set up my guitar in that C# tuning,” he says. “I can’t believe that I am 32 and I just figured out that may be a smart thing to do. It was very rewarding. I took three guitars on the road. I just couldn’t be bothered spending so much time tuning and retuning on stage, and it paid off. I think my brother really appreciated not sitting on the drums whistling to himself while I tuned in the middle of a live show.”

The guitarist fingerpicks with a raw style, using just his thumb and index finger, with his other fingers anchored to the pickguard. He plays with the flesh, or pads, of his fingers and doesn’t use his nails or fingerpicks.

TIDBIT: The White brothers made the best of the dearth of gigs incurred by the pandemic and took their time recording Petunia, creating the most high-fidelity and detailed recording in the band’s extensive discography

“I got into fingerpicking on an old nylon-string that was my first guitar,” he says. “I don’t remember a specific moment when I was like, ‘This is what I am going to do now,’ but I do remember that playing guitar for me was about using a pick—playing power chords or big open chords—and then one day I tried playing around with fingerpicking and realized I could use my thumb and index finger and that it wasn’t that hard. I started writing and fingerpicking as much as I could, and then I got into John Fahey and Davey Graham and that kind of British folk and blues fingerpicking. A few years later, when I was playing with my brother in Tonstartssbandht—our music, at first, was like noise and drone and vocal-looping based. Slowly but surely, and maybe it had to do with being able to express myself with tuning the amps correctly or finding the right guitar, fingerpicking became something we could comfortably do together. He could rip on the drums and I could fingerpick, and it wouldn’t sound too much like a hot mess. It was cohesive.”

Cohesion aptly describes the duo’s improvisations. They don’t jam in the soloist/accompaniment sense, but rather more in the group-focused style of ’70s-era krautrock bands like Can and Popol Vuh. “There are only two of us,” White says. “If only one of us is soloing, it’s going to sound pretty fucked up. We do our best to sound like a full band. If I am not playing chords and singing, I want to play leads like Michael Karoli. That feels funny—saying that Michael Karoli is my favorite guitarist—because you don’t listen to Can records for the guitars; you listen for the whole sound.”

“If only one of us is soloing, it’s going to sound pretty fucked up. We do our best to sound like a full band.”

Similarly, thanks to their combination of a practical, work-centric focus and just letting things happen, you listen to Tonstartssbandht for the whole sound. But the comparisons end there, because the members of Can, for the most part, usually wore shoes—you knew that was coming back—which, as White said, isn’t his M.O. He prefers the spiritual high and knob-twisting practicality of keeping his shoes off even if that does have its share of problems.

“It has come back to bite me,” he says. “If you play a smaller place with grounding issues, you get electrocuted that much more if you’re not wearing shoes. My dad has told me in the past, ‘Before you go on the road, go to Home Depot and get an insulated rubber mat to stand on in case you’re playing a place that has bad electricity. But as one is wont to do with their father, I hear his advice and think, ‘Shut up dad! That’s a stupid idea.’ But it’s actually quite a good idea. I should probably do it someday.”

“Falloff” by TONSTARTSSBANDHT live at Market Hotel, Brooklyn, NY, October 28, 2021

Witness the full effect of Andy White’s fingerpicked stereo sound in this vibe-y take of “Falloff,” from 2021’s Petunia.

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.