Producer Nick Raskulinecz had just begun working in the studio with the band Halestorm when he had an inspired moment. Raskulinecz decided that, rather than play their high-performance modern Gibsons, Lzzy Hale and Joe Hottinger should go for something decidedly unrefined. He handed each guitarist a 1950s Les Paul Junior, and they got to work.

“Nick decided that we needed something out of the ordinary—these old guitars that would go out of tune if you hit them too hard and just sound nasty with their P-90s,” Hottinger says.

“We faced each other in the loud room and were soon writing this wild and forceful riff that became the breakdown in ‘Skulls’,” Hale says. “Our bass player—the only real musician in the band—walks in the room and the first thing he says is, ‘You know that’s out of tune, right?’ We’re like, ‘Yeah, dude, that’s what makes it cool. It’s so wrong, it’s right!’”

Halestorm has been perfecting its brand of wrong-and-right rock since 1997, when Hale and her brother, Arejay, then 13 and 10, respectively, began writing music and performing together. In 2003, Hottinger joined Halestorm, which signed a contract with Atlantic two years later and made a big splash with a self-titled album in 2009 that followed their live 2006 EP debut.

By the time they released their third studio album, 2015’s Into the Wild Life, Halestorm had begun to branch away from straightforward hard rock and heavy metal to include pop, country, and other influences. But Halestorm’s latest album, Vicious, is a return to form, with plenty of hard-driving, down-tuned riffing from Hale and Hottinger, some pyrotechnical soloing from each guitarist, and even the occasional power ballad.

Calling from their home base in Pennsylvania, Hale and Hottinger had lots to say about their longstanding working relationship, their propensity for improvisation, the extensive tools of their trade … and the importance of playing at ear-splitting volume levels.

Let’s talk about guitars. What’s in your arsenal at the moment?

Lzzy Hale: I’m playing pretty much all Gibsons. I got two signature Explorers, a white one and a black one. I have a double-neck SG, which is a 6-string on the top and baritone on the bottom. I have a new Firebird that’s amazing. I have a Gibson Les Paul Supreme, which is amazing. I have a really hard time leaving anything under the bed, so it all comes out.

Joe Hottinger: I like a variety of guitars. I’ve got a bunch of Gibsons that are my mainstays. I just got one of the Freddie King [1960 reissue] ES-345s, and it’s got to be one of my best-sounding guitars. Whatever PAFs Gibson Memphis made for those things, I’ve got to get more of them, because they’re just amazing. [Editor’s note: They’re MHS—Memphis historic spec—humbuckers.]

I have a new Custom Shop SG in Inverness green that Gibson just came out with. It’s a really great sounding guitar. I keep going back to it and wanting to play it more. It’s so playable and fun. I also have a long-scale goldtop from the Custom Shop, which is just a really good Les Paul with Jimmy Page pickups.

I got a Manson earlier this year, one of the MA-2s with the Fuzz Factory in it and the Sustainiac in the neck. It’s just a crazy guitar. I’m having them build me another one for Europe because we wrote so many songs on that thing. And some of the main riffs in “Vicious” and “White Dress” are done just with the sound that comes out of that guitar and how unique it is. So, I’m gonna need more of those.

What else do I have? I have a Fender Master Built Tele and a Custom Shop 1964 Strat. I have a few more Teles, a baritone Tele that I put a humbucker in, and this weird Esquire-ish Tele, which Fender built to my specs a few years ago, that I always have out on tour with me.

Hale: It gets to the point when you say, “Well, let’s hang all the guitars up on the wall,” and then you run out of wall space. That’s the point that we’re at right now.

Is it hard to decide what to play on a given tune?

Hottinger: It is hard. It’s annoying, actually, because I have a Custom Shop V and a Firebird that are both killer. But they don’t get played as much as I’d like, because I’m really into the Freddie King and SG right now. So sometimes certain guitars just sit in the vault for a while, but that’s OK.

What amps are you using?

Hottinger: I have a ’71 Super Lead that I just turn up to deafening levels and this reissue Twin Reverb that I go back and forth between.

Hale: I use a Marshall JCM 800. My guitar tech and I crank it to the point where the sound guy is slightly annoyed, but not too annoyed that he’s gonna say anything. We started putting both of our amps backwards, so that we can crank them more. It’s been really interesting, because a lot of our peers are using [prerecorded] tracks onstage right now, and we’ve just never done that. So many people come up to us and are like, “How do you get your guitars to sound like that?” Our answer is always, “Well, we plug them in and we turn them up and we actually play.” Everyone is like, “Wait, really? A real guitar?”

It seems like you make fairly straightforward use of effects, but on some of your older stuff, like 2012’s “Freak Like Me,” there are some unusual sounds happening.

Hale: It’s a kind of delay effect that I make just by using my foot on a [Dunlop JC95] Jerry Cantrell Wah. I started doing that to try to make myself a better player, because I noticed the more effects that I have, the more I depend on them. And the Jerry Cantrell Wah is great, too. I can use high heels on that one because I don’t actually have to hit a button. It’s just automatically on. And as a performer, it just creates a much better effect with the audience because they’re like, “What is she doing with her foot? Oh my god, it’s crazy.”

The more that I can draw attention to the fact that I’m doing this on my own and not just hitting a button and letting things happen, the better reaction I get from an audience. But in general I’ve become quite the minimalist over the years when it comes to effects. I’m getting most of my sound from my amp, so I roll back the volume knob and use a lot of that kind of physicality.

How has your musicianship evolved since you started relying less on pedals?

Hale: I’m relying more on the tone that I create with my fingers and paying much more attention than before to how I’m using the pick. I’ve been kind of experimenting with different positions, pick-wise, with much help from Joe. I’ll be like, “Hey, man, I want to create this kind of very tight.…” And Joe will be like, “Just angle the pick this way.”

Does it go both ways with you showing each other tips and techniques? Joe, have you learned things from Lzzy?

Hottinger: Oh, yeah—totally. I remember back to when I joined the band, 15 years ago now, she’d written the riff for “It’s Not You” and it’s got this slappy left-hand thing that I had never seen before. I said, “What are you doing?” It took me a few days to get it. It was just this really cool approach to riff writing and guitar playing that I hadn’t seen before. I ended up using it in “Freak Like Me” on the second record—the same exact rhythmic thing in the verses, which keeps the song moving and chugging along.

Lzzy has such a singer-and-piano-player approach to guitar. Her vibrato is awesome. It’s such a wide vibrato. It sounds like when [Cinderella’s] Tom Keifer does a solo. When she does her solos, it’s like a voice, which is what it should be.

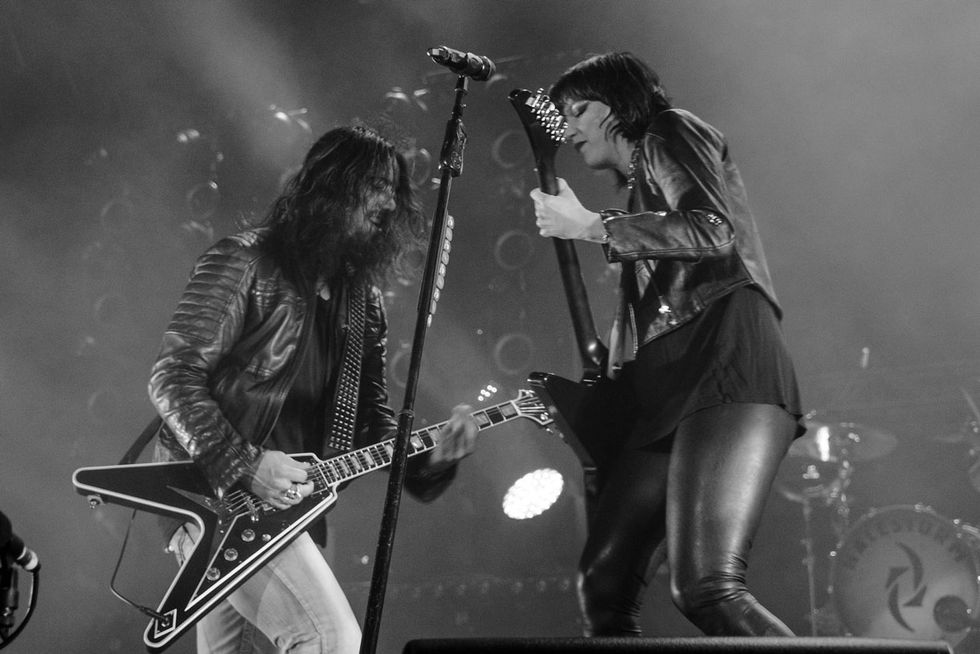

Hale recalls that until she and Hottinger met in their teens, she had never known anyone as obsessed about music as her. They immediately began having marathon late-night practice sessions. Photo by Annie Atlasman

You mentioned playing with your amps cranked. How important is sheer volume to your music, both in the studio and live? How does it affect the ways you approach the guitar?

Hottinger: To me, live … it’s everything. If I let go of the guitar, it needs to start feeding back. I have to be on the brink of a feedback meltdown, otherwise it’s dead to me. It sounds terrible and you’re just fighting to get these notes out. I hit the guitar too hard when the amp’s not cranked. I just started on this tour, for the first time, plugging in my backup cabinet and doing the Bruce Springsteen thing. I have it laying down, aiming up behind me. I don’t know what angle it’s at, but my guitar tech put it there and I love it.

I have the Super Lead turned up so loud we have to point its cab backwards—that’s the miked cab. But I also have monitors in front of my pedalboard that are blasting. That cabinet that’s aimed straight up … I can walk back to it and just get the guitar to start humming and vibrating—especially that 345, that [semi] hollowbody. It’s such killer feedback when you get back by that cabinet. So yeah, volume is everything for the tone live. I don’t comprehend how some of these bands play with Kemper [profiling] amps. It would feel so dead to me.

Hale: It’s not part of our DNA. I think it just comes all the way back to when you first start playing guitar and the first thing you want to do is get really loud and try to annoy the neighbors. For us, it was just fun to do that. We both experimented with the after-effects and the Kemper stuff. Some of it is really great for making demos and all that, but for the most part, any time that we would ever try to do it in a live setting, it’s like, “Wow, it just sounds the same [as everyone else] and doesn’t feel good.”

Lzzy Hale’s Gear

GuitarsGibson Lzzy Hale signature Explorers

Gibson Firebird

Gibson Les Paul Supreme

Gibson custom doubleneck SG (6-string and baritone)

Amps

Marshall JCM 800

Effects

Klon Centaur

Dunlop JC95 Jerry Cantrell Signature Cry Baby Wah

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball (.010–.052)

InTune GrippX

For me, if you don’t feel like an absolute rock star—like you’re 13 years old bouncing up and down on your bed with your first guitar—it affects your performance, and it affects how the crowd reacts. To me, that’s 101. That’s the basis of how you’re supposed to feel when you walk onstage.

Vicious is a return to your harder roots. Can you talk a little bit about what inspired that?

Hottinger: We’ve been saying that this record is like a rebirth for us. We went in the studio with Nick Raskulinecz, who’s just such an awesome dude and a great producer. We had written a bunch of songs and we didn’t like them, which is so stupid. They were good songs, it would’ve been a good record, but it felt like a rehash. We were like, “I don’t think this is what we should be doing.” We showed them to Nick and he was like, “I don’t want to make this Halestorm record.” We were like, “Good. We’re on the same page.” Then it was like, “Oh shit.”

Hale: Now what do we do?

Hottinger: We didn’t actually know what to do to push the band forward and push ourselves forward and maybe push our listeners and maybe, if we’re lucky, push the genre. How do you do that? He was like, “Worry about yourself. When was the last time you just sat in the room and played together?”

“Who’s got a riff?” were the famous first words of the record. I’m like, “Well, I got a bunch of riffs—let’s start there.” So we did. We just started jamming together, the four of us, and did two different two- or three-week sessions of that. We realized, “Oh, we got this. This is fun. That’s actually a cool part.”

And then over the next bunch of months, Lzzy and I really found our mojo and started writing a bunch of songs and demoing them up at home or doing it with the four of us. Lzzy would write a song and we’d figure out how to play it as a band. We just found our groove. Nick said it well: “If you’re excited about the music, then I think your fans will be excited, too, because they’ll be able to hear that.”

We’ve said it before—we weren’t trying to make a heavy record, though we wanted to make a rock record, for sure. A lot of bands in our genre have given up on rock and incorporated these pop-synth sounds, shying away from guitar rock ’n’ roll. We wanted to double down on our guitar rock ’n’ roll and make a statement that rock is still valid.

Hale: We didn’t realize that we were making a heavy record until we started playing some of the songs, like “Black Vulture,” live. That’s a huge testament to Nick, because what he did was basically take everything that we love about being in this band—all of our personalities and everything that each of us brings to the table—and then just kind of amplified that. This is the most Halestorm record that we’ve done. It’s like us—but up to 11.

There were so many moments where we were like, “Yeah, that totally rocks,” and then Nick would be like, “Oh no, no, no. I’ve seen you guys live. I’m a fan of your band. I know that you can sing higher. I know that you guys can play louder. You can play faster. I know your little brother [drummer Arejay Hale] is crazy. We gotta push it just a little further.”

Brash, bratty rock ’n’ roll attitude remains an important part of Lzzy Hale’s and Halestorm’s recipe for success onstage and in the studio. Photo by Ken Settle

Describe how you write together and how you determine the division of labor between your guitar parts.

Hottinger: There is no set way, especially in getting to the core of the song. Like “Uncomfortable” is an instrumental piece. We wrote all the music for that first, then Lzzy got tasked with singing something over it. Then, when we started recording it and playing it live, we had to figure out who’s gonna play that riff, who’s gonna play this. Neither of us is precious about our guitar parts.

Joe Hottinger’s Gear

GuitarsFender Custom Shop Esquire

Fender Custom Shop 1964 Stratocaster

Fender Baritone Telecaster

Fender Master Built Telecaster

Gibson Custom Firebird

Gibson Custom Flying V

Gibson Freddie King 1960 ES-345

Gibson Custom goldtop Les Paul (long scale)

Gibson Custom SG

Manson MA-2 with Fuzz Factory and Sustainiac

Amps

1971 Marshall Super Lead

Fender Twin Reverb reissue

Effects

Eventide H9 Harmonizer

Ibanez TS808 Original Tube Screamer

Keeley 30 ms Automatic Double Tracker delay

RJM Effect Gizmo loop switcher

RJM Mastermind LT MIDI foot controller

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball (.010–.052)

InTune GrippX

Hale: A lot of times, even after the recording is done, Joe and I will sit down and make sure that each of us is playing the part that makes the most sense. Like Joe said, we’re not precious with either of our parts. A lot of times we end up switching and swapping—you do the solo there, I’ll do this here. You’re singing over that so maybe you should do this part here—that kind of thing.

It’s fun. The two of us—we’ve been best friends for 15 years now, from the very beginning. When we first met, besides my little brother, I had never met anybody who was obsessed with music as much as I was. I was one of those people who are like, “Dude, you live and breathe this, this is not just a career choice. This is an extension of you.” He and I would literally play together and write together and listen to music together until 4 in the morning and be like, “Oh, crap, I guess we should be normal people.”

It’s awesome to know somebody on that level. A lot of times, we don’t even have to talk about stuff. We have this amazing musical language onstage now, we’re able to do these improv sections where we don’t really know how we’re gonna end things. But between the four of us, we can give each other a look and figure out how to make these moments with these crowds and then somehow bring it back around to end the song. It’s pretty fantastic to have that kind of relationship with people.

Regarding improvisation—is that something new, bringing it into your live set?

Hottinger: We’ve been doing it a few years—picking a song and just going off on it and trying to make it different and exciting every night. To me, that’s where music is alive: in front of a crowd, pure improv, just expression, the four of us speaking rhythmically at each other. I love throwing weird rhythms in an improv solo with Arejay, and he’ll talk with me. He’ll leave me with a rhythm and we’ll go on a triplet run or something—just fun moments coming together and trying to make this explosion, to make the crowd go, “Woo!” It’s really alive and exciting, because you can fail, and we have failed. We’ve had some real bad jams, like, “Whoa, let’s end this. We’ve gotta move on.”

Hale: We haven’t had the total train wreck yet, but there have been some performances where afterwards we’re like, “Wow, that could’ve been really great and it totally wasn’t.”

Hottinger: [Laughs with Hale.] Let’s not do that again!

YouTube It

Halestorm perform one of their signature songs, “I Miss the Misery,” on May 10, 2018, at the Santander Arena in Redding, Pennsylvania. Lzzy Hale rocks one of her Gibson signature model Explorers, while Joe Hottinger demolishes the solos with his Gibson Custom Shop-built Firebird.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)