“Jamaaladeen Tacuma is the hardest-grooving bass player I’ve ever worked with or heard,” gushes guitarist Marc Ribot. A heavy endorsement and, no doubt, a very sincere one. The two musical iconoclasts have worked together extensively, developing a strong musical rapport over the course of their careers. But it doesn’t take a close collaborator to spot Tacuma’s unique sound. Whether holding down the groove or bursting at the seams with improvisational energy, the bassist has a signature instrumental voice and infectious feel that’s immediately recognizable.

Tacuma developed his risk-taking approach to the bass at an early age. As a young man, fresh out of high school, Tacuma turned down a scholarship to Berklee College of Music, opting to hit the road. He soon ended up getting a call from the pioneering saxophonist Ornette Coleman, who was looking to form a new group with electric funk instrumentation.

Suddenly immersed in the free-jazz innovator’s bold musical concepts about improvisation, production, and arranging, Tacuma became a pivotal member of Coleman’s Prime Time band and played on a series of unique and adventurous albums, such as Dancing in Your Head, Body Meta, Of Human Feelings, Opening the Caravan of Dreams, and In All Languages.

Tacuma’s experience under Coleman’s tutelage as well as his willingness to throw himself into new projects with zeal have served as a deep foundation for his own work as a bandleader, producer, and bass player. Ribot explains, “Somehow this huge enthusiasm he has as a person gets communicated through the bass. As an improviser, Jamaal has been through deep training with Ornette in the Prime Time band. Those two things fuse into an entirely original language of the bass—he can improvise with the most out music without losing one ounce of groove.”

Outside of his work with Prime Time, Tacuma has led a busy life, releasing a string of solo releases starting in the early 1980s with Show Stopper and Renaissance Man. He also quickly became an in-demand side musician, working with such artists as Ribot, James Blood Ulmer, James Carter, Derek Bailey, Steve Jordan, and Vernon Reid. His eagerness to explore and experiment has led to cross-cultural collaborations with artists from across Europe, as well as Turkey and Morocco.

All the while, he’s made time for younger up-and-coming artists. In Questlove’s memoir, Mo’ Meta Blues: The World According to Questlove, the drummer credits Tacuma for bringing the Roots to a wider audience by inviting them to perform at their first European festival. Tacuma continues that kind of curatorial thread to this day with his annual Outsiders Festival, where he brings together improvisors from various musical disciplines and locations to perform a series of concerts every April in Philadelphia.

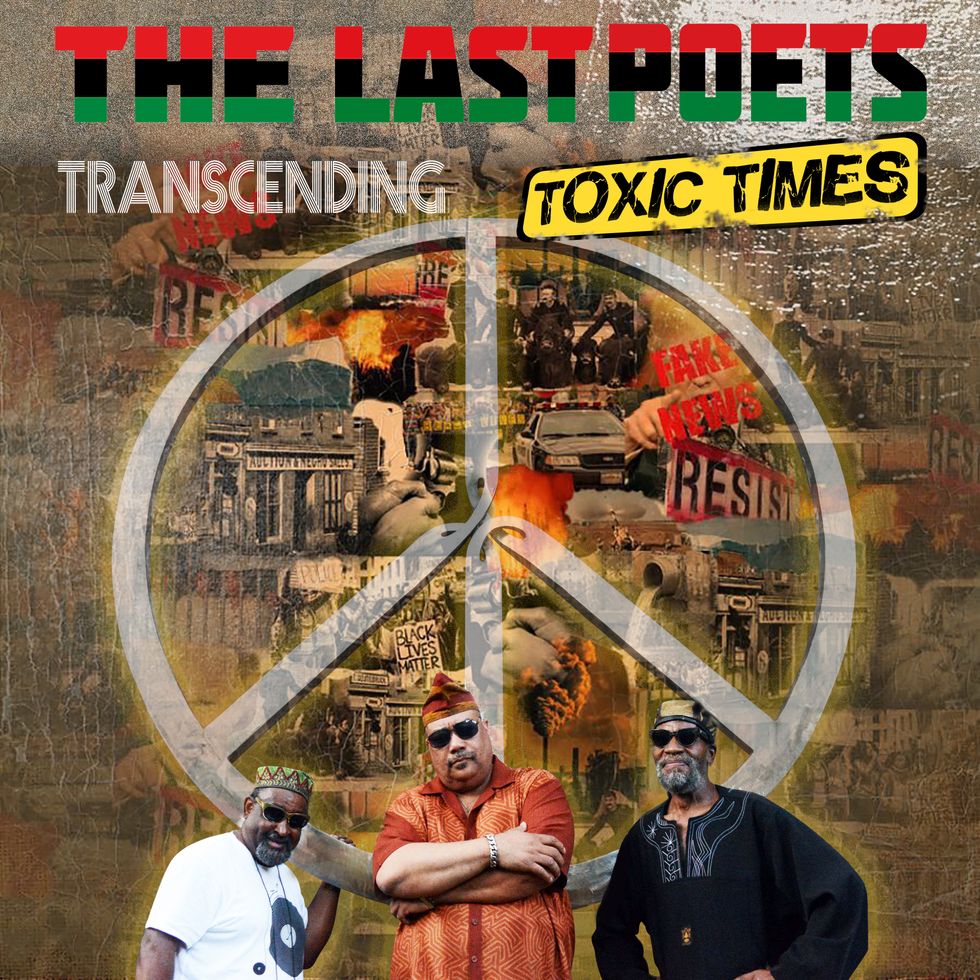

This year, Tacuma produced, wrote the music, and played bass on proto-hip-hop pioneers the Last Poets’ newest LP, Transcending Toxic Times. The result is a funky take on the legendary group’s sound. Tracks like “For the Millions,” “A.M. Project,” and “If We Only Knew What We Could Do” blend contemporary sounds with vintage grooves and, more than 50 years after the Last Poets’ self-titled debut album, the group sounds as powerful and timely as ever.

PG called Tacuma at his Southwest Philadelphia home to discuss his path as an artist, from his work with Coleman to Transcending Toxic Times, and got into a deep discussion with one of the best-dressed men in music.

How did you come to work on the new Last Poets’ album?

I’ve known about the Last Poets since I was about 16 years old. I was very excited about them and what they were talking about at the time—we’re talking late ’60s, early ’70s. They were addressing issues that affected me as an African-American man here in America. Being a little younger, I didn’t really know what was going on worldwide, but I think they were responsible for bringing all that sort of information to me, that knowledge.

Once I had a concert here in Philadelphia with a local band and they were gonna be coming on, so I introduced myself and told them that I wanted to play this one song with them, “The Creator Has a Master Plan” [by tenor saxophonist Pharoah Sanders]. So we performed that tune.

Some years later, there was this sort of 40th anniversary of the Last Poets tour with all the original members, and with myself, Bobby Irving from the Miles Davis band, drummer Ronald Shannon Jackson, and another percussionist. After that tour, in the musical set I noticed some things I would like to make improvements on. So, we go forward a few years and I had been awarded a grant from the Pew Center for Arts & Heritage in Philadelphia. With some of that money, I went into production for a recording with them.

From the first time I heard the second track on the album, “For the Millions,” it’s been stuck in my head. I think a big part of that is the way the bass and drum groove gets things started after the spoken word on the first track. It’s kind of like that’s a mission statement for the album.

I envisioned all the material that they were utilizing in the live show in a very raw and organic stage, and envisioned the idea of sequencing. What is the emotion going from one track to the next? Further down in the album, you have all of these different dynamics and you have a tune like “Young Love,” which is more of a ballad, and you have some things that were happening beforehand that sort of brought you to that point.

So “For the Millions” had a certain groove happening that was very contemporary, very upbeat, and also very percussive. I wanted to evoke a certain feeling of an original live band. Aside from a few things I did later in the production, we basically cut all the music for the record in one day with keyboards, guitar, drums, and bass.

Tacuma produced and played bass on proto-hip-hop pioneers the Last Poets’ Transcending Toxic Times, which was released this year. “I wanted to evoke a certain feeling of an original live band,” he says. “Aside from a few things I did later in the production, we basically cut all the music for the record in one day with keyboards, guitar, drums, and bass.”

You are pretty passionate about the concept of improvisation and the way the improvisation relates to music. How does that translate to production?

Working with Ornette Coleman allowed me to see how a record was done in an improvisational way. You could go to the studio, you can have already done-up compositions and arrangements and approach it that way, or you can go into the studio and you can do a recording where no one has ever rehearsed together and create a certain sound, create a certain movement in the music. In that way, you’re depending more on the proficiency of the individual artists that you have curated to perform that record.

When you have a composition, the composition kind of speaks for itself—everybody’s playing the chords, everybody’s playing the notes. When a person solos, you begin to hear a certain emotion and a certain individuality, and there’s more of that in a completely open compositional piece.

Ornette Coleman’s music has had a profound effect on so many people, and you spent much of your formative years in his band. What were you doing before you met Ornette and how did you begin working together?

I grew up in Philadelphia. I attended a development project called Model Cities, which was an organization that had after-school programs for youth and provided musical instruction and mentorship. My bass teachers were Tyrone Brown [bassist with Max Roach and Grover Washington Jr.] and [longtime Art Blakey bassist] Jymie Merritt. There were other musicians that were sort of mentors, like Odean Pope, Eddie Green, and Sherman Ferguson. They had a group called Catalyst that were the backup band for Pat Martino.

When I got out of high school, I had an opportunity to go to Berklee College of Music. I had a scholarship. I chose not to go there because I wanted to get into the thick of it and be a touring musician. I would actually say that the information that I was able to pick up off the road is a little bit more valuable than probably what I would have learned at Berklee at that time.

My very first job was with an organ player, Charles Earland, who took me on. After playing with him for about a year, I got a call from Reggie Lucas, the guitar player with Miles Davis. He and James Mtume, who was also with Miles Davis, suggested that I play with Ornette Coleman, so I went on the road with Ornette. We were supposed to go to Europe for two weeks and we wound up staying in Europe for six months.

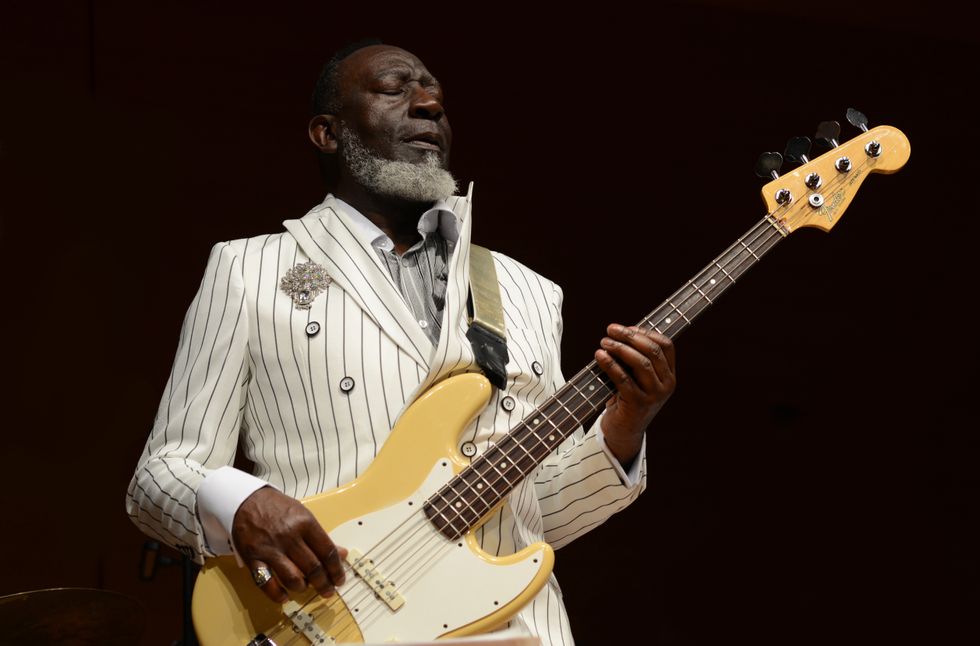

In addition to being revered for his hard-grooving lines, Jamaaladeen Tacuma is widely known as a sharp-dressed man. “Those people who are just gonna get up there in a T-shirt,” he says, “yeah, that’s fine, but it’s boring and everybody knows it.” Photo by Sound Evidence

Ornette Coleman’s music was based on his concept of harmolodics, which is the way he defined how he wanted instruments to relate to each other in his music. How did his ideas affected you and how you play the bass?

When we think of the bass guitar, we normally think of an instrument that is the anchor in the band, that provides a foundation, and plays a supporting role to everything that’s going on musically. That instrument is, to this day, not really looked upon as being an equal instrument in an ensemble. Like, we need the bass player, but when you really look at it, you have the guitar player up front, you have the saxophone player up front, you have the trumpet player up front, and the keyboardist up front, we have a vocalist up front, but, in fact, the bass guitar is the thing that is keeping it all glued together.

Ornette gave me insight into thinking about the bass as being an equal instrument in the ensemble that was free to play melody, that was free to incorporate various sounds. So the bass guitar, for me, morphed into a new way of thinking, a new lifestyle.

When I think of the bass guitar in my work and how I work with others, I think of it in several terms. If I am in a supporting role that’s going to give the foundation to the band, I’m going to drive that band and I’m going to give it everything I’ve got as a bass player. I’m gonna lock with the drummer and I’m going to just glue that thing together and keep it rolling.

When I’m thinking of myself as an improviser, I incorporate that idea, as well as the idea of being an improviser who is completely moving out of the realm of what the bass is thought to be about. I will admit that when I hear my stuff on record, I say, “This is some wild stuff,” because it is very different and all of a sudden, you hear me spin off into an improvised thing that’s based on the melody or whatever, then all of a sudden you might just hear me groove. That’s what makes it interesting to me, and those are the things I learned with Ornette.

It’s interesting to consider the role of a specific instrument when improvising. If you’re only playing your instrument in its expected roles, you might not be improvising or experimenting to the fullest potential.

Right, and you know why? Because that instrument, in my case the bass guitar, would have put shackles on me, would have put limits on me. It would make you not free. The instrument itself is actually putting you in prison.

People always thought that Ornette, or myself for that matter … we’re just playing, we’re not thinking, but that’s not the case at all. It’s mainly compositional improvising where the melody or the composition is the most important factor in the whole scene. I’m digging into that, I’m borrowing from that, I’m working through that, and I’m trying to make it even stronger than the melody.

You want to make whatever you play interesting, the way to do that is to be able to play something that is equal to the melody or absolutely better in terms of your musical ideas, and not to get tied down. Playing compositionally, you’re not thinking about these regurgitated kinds of musical gestures. You’re thinking about musical ideas, which are endless.

That allows you to play in a more personal way.

Because my ideas are different than yours. There’s no one on this planet that has absolutely the same ideas all the time. That’s what makes life so interesting. If I design a jacket, the jacket might be orange but I might make one sleeve yellow as opposed to somebody who might say I’m just going to make the whole jacket orange.

Basses

Steinberger L2

NS Design WAV4 Radius

1972 Fender Jazz

1980 Fender Precision

1960s Kay Speed Demon

DiPinto Belvedere Deluxe

Amps

Aguilar Tone Hammer 500

Aguilar DB 2x12 White Hot cabinet

Aguilar SL 1x12 cabinet

Effects

Korg ToneWorks G5 Bass Synth

JAM Wahcko Bass

JAM WaterFall Bass

JAM LucyDreamer Bass

Aguilar Octamizer

Aguilar AGRO Bass Overdrive

Strings and Picks

La Bella sets in various gauges

I’m glad you mention that, because your style is something that is really important to your work. Anyone who has ever seen you perform, going all the way back to the ’70s, knows that there is a strong connection between your visual style and your music.

The visual is important, as well as the audio. If I go to an opera and I’ve been to the same opera last year and I like the music, I don’t want to go to the opera and see the same set design, I don’t want to go to the opera and see the same costume design. I would like to see something different. That music is always gonna be the same and it’s beautiful as it is, but what gives it that extra jump is that collaboration with the set designer or costume designer who’s going to take that work to another level.

It’s the same thing when all of us as individuals are hitting that stage, hitting that television program, hitting that concert hall, hitting that little club around the way. A person is gonna come out there to see you, but they’re also going to come and see what you are wearing, what you are dealing with, and how you project yourself from a visual standpoint because that’s important as well.

Those people who are just gonna get up there in a T-shirt, yeah, that’s fine, but it’s boring and everybody knows it. It’s almost like when you go to a wonderful restaurant. Yeah, you’re going for the food, you know the food will be cool, because you know the owner, you know the person is picking the best quality-sourced food. But you know when that food hits the plate, the visual aspect is going to bring a smile to your face. I’ve always known that.

Showing up onstage dressed sharp is a way to show you’re serious about what you do.

The most important example of that was with Ornette. I think that’s why we had such a good relationship. He saw in me early that I was a young guy who not only was trying to play the best I could play, trying to create the best sound, but was also interested in the best presentation, because he did it all the time.

There’s a theater here in Philadelphia called the Uptown Theater, and that’s where I saw all the groups of the ’60s and ’70s. You had everybody looking sharp, from the Who to Grand Funk Railroad, Jimi Hendrix, Chicago, the Chi-Lites, James Brown, Chaka Khan, and Blood, Sweat & Tears. That was the thing to do because it was just part of the whole scene. That has carried with me. When you’ve got these musicians who are improvisers and want to go up onstage and just look like anything, that doesn’t make any sense.

You’ve played a lot of great basses throughout your career. All of them have looked pretty great, too!

Instruments have always been important to me from the visual aspect. I’ll really enjoy the way that they sound, but I’m not really a technician. I’ve never really been interested in all of the technical aspects of amplification or guitars. I just put my hands on it and just start rippin’. I would leave the rest up to everyone else who dealt with that. I just want to pick the thing up onstage and play it. You know, it’s all in your fingers.

When I first started playing bass, I had a white, Japanese Kimberly hollowbody bass—the coolest-looking bass I ever saw. My mother and I were walking down Erie Avenue here in Philadelphia by a pawnshop and I looked up in the window and I saw this bass and said, “If I was to learn how to play bass, I would love that.” About two or three weeks later, I come home from school and on my bed was the bass. From that moment on, I stayed in my room for one year, just learning how to play.

My second bass was a sunburst Fender Mustang with a pearl pickguard. Then I moved into a Rickenbacker bass, the 4001 stereo. I was 18 years old and that’s the bass I started playing with Ornette Coleman on Dancing in Your Head, Body Meta, and Of Human Feelings.

When I was introduced to Ned Steinberger, I was given one of the prototypes right off the table when they were quite new. I was touring with that because they were so small, it was nice. Later on, I was introduced to Chris DiPinto because I wanted a goldtop hollowbody bass, and he came up with the Belvedere Deluxe with all the bells and whistles.

You no longer travel with your basses, right?

I would always have bad luck traveling. They were always losing my luggage and they lost one of my Steinbergers in the Newark airport, so the light bulb went off in my head. I said I would never travel with any of my bass guitars again. So, when I do these jobs with these promoters, there just has to be a Fender Jazz bass or a Fender P bass. I tweak it a bit so it plays right and then I just put my hands on it and rip.

Filmed inside Philadelphia’s City Hall, this video is a rare document of Jamaaladeen Tacuma playing solo, distilling his vibe to the essentials. Using a clean tone, he runs through a theme with variations built around a walking bass line. Throughout it all, he grooves.

After one of his Steinbergers disappeared at the Newark airport, Tacuma vowed to leave his personal basses at home and rely instead on concert promoters to supply him with a Fender Jazz or Precision bass. “I tweak it a bit so it plays right,” he says, “and then I just put my hands on it and rip.” Photo by Sound Evidence

Jamaaladeen Essential Listening

James Blood Ulmer, Tales of Captain Black (1978)The tunes on this album were all composed by James Blood Ulmer, but the band and concept is essentially that of Ornette Coleman’s Prime Time band with Ulmer on guitar. Check out how Tacuma’s bass playing responds to the melody on “Moons Shine,” which begins at 3:14.

Ornette Coleman, Of Human Feelings (1982)

Tacuma’s bass kicks off “Sleep Talk,” the lead track from the third release by Ornette Coleman’s Prime Time band. This performance offers a classic example of the ensemble’s sound and aesthetic.

Jamaaladeen Tacuma, Show Stopper (1983)

Tacuma’s debut record as a leader. On the album’s title track, his work as a producer and arranger is on strong display.

Derek Bailey, Jamaaladeen Tacuma, and Calvin Weston, Mirakle (2000)

Tacuma and drummer Calvin Weston have worked as a rhythm section in countless bands and have developed a nearly telepathic improvisational language. Here they join free-improvisation pioneer Derek Bailey for a series of adventurous explorations. Tacuma grabs the reins on the second track, “What It Is” (16:35).

Marc Ribot’s Young Philadelphians, Live in Tokyo (2014)

Tacuma drives the beat and takes an extended solo on “Love Rollercoaster” from Marc Ribot’s raucous live record of funk party jams.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)