B’lieve I’m goin down... is Kurt Vile’s sixth album and the eagerly awaited follow-up to his 2013 breakthrough Wakin on a Pretty Daze. Recorded at seven different studios over more than a year of couch surfing and late-night sessions, it’s a trippy and revealing portrait of a singer-songwriter whose reverence for classic sounds is shaping a new breed of indie rockers.

When Kim Gordon declares she’s your biggest fan by writing the press bio for your latest album, you’re probably doing something right. As an almost accidental working-class hero of Philadelphia’s sprawling music scene, Kurt Vile deserves every accolade he gets, even if his quirky brand of woozy, psychedelic folk-rock is on the verge of shattering the underground ceiling and going mainstream. A recent two-night stand of packed shows at New York City’s Webster Hall tells the current story: Vile and his backing band the Violators are a musical force to be reckoned with, but the hype has nothing to do with “selling out.”

Put simply, Vile has tapped into a need—a quasi-spiritual calling, if you will—to make music that’s primal yet provocative, rebellious yet revelatory. It’s this innately down-to-earth throwback quality, drawing from influences as far afield as Bob Dylan, Neil Young, John Fahey, Royal Trux, and Pavement, that drew Gordon to his orbit and places Vile at the vanguard of a rising tide of 30-something artists—including his former bandmates in the War on Drugs (fronted by ace guitar-slinger Adam Granduciel)—who are looking to the ’70s rock canon and its ’90s revival to remake the future, all while staying true to do-it-yourself principles.

“For me, when I’m playing any instrument, it’s fun to not be bothered about theory or traditional technique,” Vile explains. “There’s all these obvious things you know anyway, even if you don’t know them by name. I mean, I’ll capo something and put it in a different tuning, and I’ll intentionally not think about the notes. I like the idea of not knowing too much about music, but just trying to be musical. You can pick up anything—a banjo, a guitar, a piano—and just find the notes. That’s the beauty of it. It’s sort of punk rock, but it’s more of a melodic, musical thing—like utilizing the two and figuring it out for yourself, and just keeping at it. By default, you’re gonna develop your own style.”

Since he was first signed to the venerable Matador label in 2009, Vile has made it his trademark to chase new sounds with a well-honed sense of curiosity that’s just as insatiable as his apparent lust for guitars. It all started at age 14, when his father, a fan of Doc Watson, Rusty & Doug Kershaw, Charley Patton, and other blues and bluegrass greats, gave him a banjo—a fateful choice for a kid who was already watching most of his friends jump feet-first into rock bands. As it turned out, the instrument defined his playing style before he’d even found one.

“Obviously that helped out my perspective in general,” he says. “If I’d had a guitar first, I probably would’ve gotten lessons and been stuffed in the barre chord box, whereas the banjo, with the open tuning—like on the song ‘That’s Life, Tho’ [from the new album], it’s not a far cry from that. It’s very Appalachian. But I’ve always favored open G because that’s all you need to start playing music. You’ve just got to adapt that to the guitar later in life. I played banjo for maybe a year before somebody gave me a guitar—maybe even a little more. But all my friends were starting in bands, so I’d pick up their guitars. I was writing songs for guitar before I actually owned one, and then one day a guitar just showed up at my house.”

Kurt Vile now has two ’64 Jaguars: one for standard tuning, one for open tunings. “Pretty much every electric song on the album is that guitar,” he says. Photo by Nathan Edge

Vile also had a Regal resonator guitar as a kid, and that instrument defined his early lo-fi sound on his debut compilation Constant Hitmaker and the follow-up God Is Saying This to You.... “You can hear it on songs like ‘Slow Talkers’ and ‘Can’t Come,’” he notes, “and there’s plenty of others, but I stuck with that resonator as basically my acoustic sound. I considered it my acoustic after a while.”

With 2009’s Childish Prodigy, Vile raised his game by bringing his touring band the Violators into the studio (whose lineup then featured Granduciel on numerous guitars and electronics) and delivering a knockout mix of jagged, Crazy Horse-style riffs, cavernous reverb, and kinetic beats, all hammered home in songs like the 7-minute road-trip jam “Freak Train” and the lead-footed “Hunchback,” which was about as archly Tom Petty-ish as Vile might ever dare to sound.

He teamed up with producer John Agnello, known for his work with Dinosaur Jr., to track 2011’s Smoke Ring for My Halo. Composed almost entirely on a Martin dreadnought, the album was much more acoustic-based than anything Vile had done previously, with finely articulated fingerpicking on songs like “Baby’s Arms” and the haunting ballad “Peeping Tomboy.” As his guitar collection grew to include such exotic pieces as a DiPinto Belvedere Deluxe and a vintage Greco Les Paul copy, Vile continued to tour relentlessly and expand his horizons. Chasing something new and different, he joined Agnello again to create the undulating wave of sound that colors Wakin on a Pretty Daze. Together, they crafted what many considered to be Vile’s masterpiece—a spacious foray into beautifully flanged guitars (“Wakin on a Pretty Day”), classic rock riffs (“KV Crimes”), dreamy folk-pop (“Shame Chamber”), and cosmic Americana (“Goldtone,” aptly featuring his Gold Tone resonator) that plays as a cohesive “concept album” from start to finish.

“I was writing songs for guitar before I actually owned one,” says Vile, “and then one day a guitar just showed up

at my house.” Photo by Marina Chavez

With b’lieve I’m goin down..., Vile wasn’t seeking to top the success of Wakin on a Pretty Daze. “I think the sound of Wakin probably had to do with John Agnello’s production, as far as it being a different kind of guitar wall. This album is more stripped-down, more open because there’s less going on. Sometimes one guitar can seem louder than five guitars, you know? That’s one role it can have, anyway. But in general, it has to do with all kinds of things—the production, the playing. It’s always hard to put a finger on it, but depending on which track it was, we kept it pretty much insular and within the band this time.”

In fact, two of the Violators—guitarist/bassist Rob Laakso and recently recruited drummer Kyle Spence (of J Mascis and Harvey Milk fame)—handled the bulk of the recording, with the legendary Rob Schnapf (Elliott Smith, Guided by Voices) stepping in to produce the album’s two bookends, “Pretty Pimpin” and “Wild Imagination.” Along with multi-instrumentalist Jesse Trbovich (also a member of the Violators), musical guests include Warpaint drummer Stella Mozgawa and Beachwood Sparks’ Farmer Dave Scher, whose lap steel flavors “Wheelhouse,” the album’s arguable centerpiece, and the brazenly outlandish (in a good way) “Lost My Head There.”

Tracked in studios from Brooklyn to Joshua Tree, b’lieve I’m goin down... captures the feeling of restlessness that seems to fuel Vile’s vivid imagination. As much as he may seem spaced-out, distracted, or “oiled-up,” as he likes to refer to his state of mind during an all-night recording session, Vile can’t shut down his brain, whether he’s strumming at home on his couch or racking up frequent flyer miles. From the mournful banjo melody that propels “I’m an Outlaw” to the unusual West African-style tuning of “Wheelhouse” (more on that later) to the deftly picked Gold Tone on “All in a Daze Work,” goin down is a catalog of influences that coalesces around Vile’s uncanny ability to write songs that hit you at gut level.

“I think it’s all about the subconscious domino effect,” he offers. “Everything just influences the next thing, and without giving it a name, it all starts to blend together. If you don’t ask questions, the riffs, the songs, the sounds all develop on their own, you know? Don’t try to analyze it too much. I’ve been playing long enough to know that if I don’t think too hard about what I’m doing, it just keeps coming.”

What are the main guitars you recorded with?

There’s a great company in Philadelphia called Vintage Instruments, and since they have a history of fixing vintage acoustics, they have these Martin custom jobs. I have two Martins from them—one is a 00 version that’s based on Martin’s Philadelphia Folk Festival Anniversary Edition.

And then my main electric guitar is a ’64 Fender Jaguar sunburst, which I bought in 2011 [at Gruhn Guitars in Nashville] when I was on tour. I’ve started concentrating on that in general. A lot of people get stoked on buying tons of different guitars, which is awesome, but I just thought, “How can I get inside this thing and make it my main electric guitar?” So I really focused on getting familiar with it, so much so that I just bought another ’64 Jaguar for the road. So now if I want all the different tunings, with help from my guitar tech I can keep playing the whole set with the Jaguar. Pretty much every electric song on the album is that guitar. There may be a few exceptions, but that’s what I’m concentrating on.

Kurt Vile's Gear

Guitars and Fretted InstrumentsTwo ’64 Fender Jaguars (one for standard tuning, one for open tunings)

Martin custom 00 hybrids

Martin DC-16RGTE (played live)

Gold Tone PBS-D resonator

Buckeye 5-string banjo

’61 Guild Starfire (for playing around the house)

Amps

’67 Fender Bassman

Fender Deluxe Reverb (blackface reissue)

Effects

Trbo Booster (designed by Jesse Trbovich)

Russian Big Muff

Mountainking Electronics OCM digital noise generator

Line 6 FM4 Filter Modeler

MXR M169 Carbon Copy

Dunlop wah

Strings and Picks

D’Addario EXP14 light top/medium bottom bluegrass acoustic (.012–.056)

Ernie Ball Beefy Slinky electric (.011–.054)

You tracked a clutch of songs at Rancho de la Luna in Joshua Tree, and you’ve talked about jamming with [Malian blues-rock band] Tinariwen there as the inspiration for “Wheelhouse.”

Yeah, I came up with some weird tuning that morphed out of jamming with them at Rancho. I’m not going to tell you what it is because it’s so weird that I want to keep it a secret [laughs]. But people will be able to figure it out on YouTube. At the time we recorded it, this was a brand new song, and I wrote the lyrics really quickly. I was just easing into it with Stella [on drums] and Farmer Dave [on lap steel]. Rob [Laakso] plays a bass outro at the end of the song, but originally he recorded just the three of us. So the guitar part has this weird arpeggio, and then everybody locks in, just reacting off of each other. They hadn’t heard the song really at all, but they responded to the lyrics. Farmer Dave does these weird, awesome things where he listens to the lyrics and tries to get that sound out of his guitar, basically acting out what you just said. So that’s our magic moment captured in the desert.

We may have used a Supro [amp] on the guitar sound for that. Rob fine-tuned the sound and got some good reverb. He also brought in an Aqua-Puss analog delay pedal that’s hardly open—mostly it’s just pure electric guitar, with lap steel and keyboards from Dave, and Stella’s raw-sounding drums. It’s just a pure sound, and that’s why I love it. With the way Dave is playing these washes around the minimalism of the guitar, you can hear that there’s not that many tracks, but it’s trippy and loud anyway. That’s the idea. There’s a lot more mileage in a song like that, when a single guitar can go almost right into your soul.

For his stage acoustic, Vile favors a Martin DC-16RGTE. Photo by Lindsey Best

With all the different studios you record in, does a sense of place ever find its way into a song for you?

Yeah totally, it does, but you couldn’t put it in words. A song like “Wheelhouse” is sprawling and wide open, and it’s not far-fetched to say that it sounds like the California desert. Your surroundings influence you in mystical ways that if you thought too hard or tried too hard to explain or put into lyrics, it’s like you’re asking too much, you know? Just let it happen, take the influence and don’t even ask about how it gets in there.

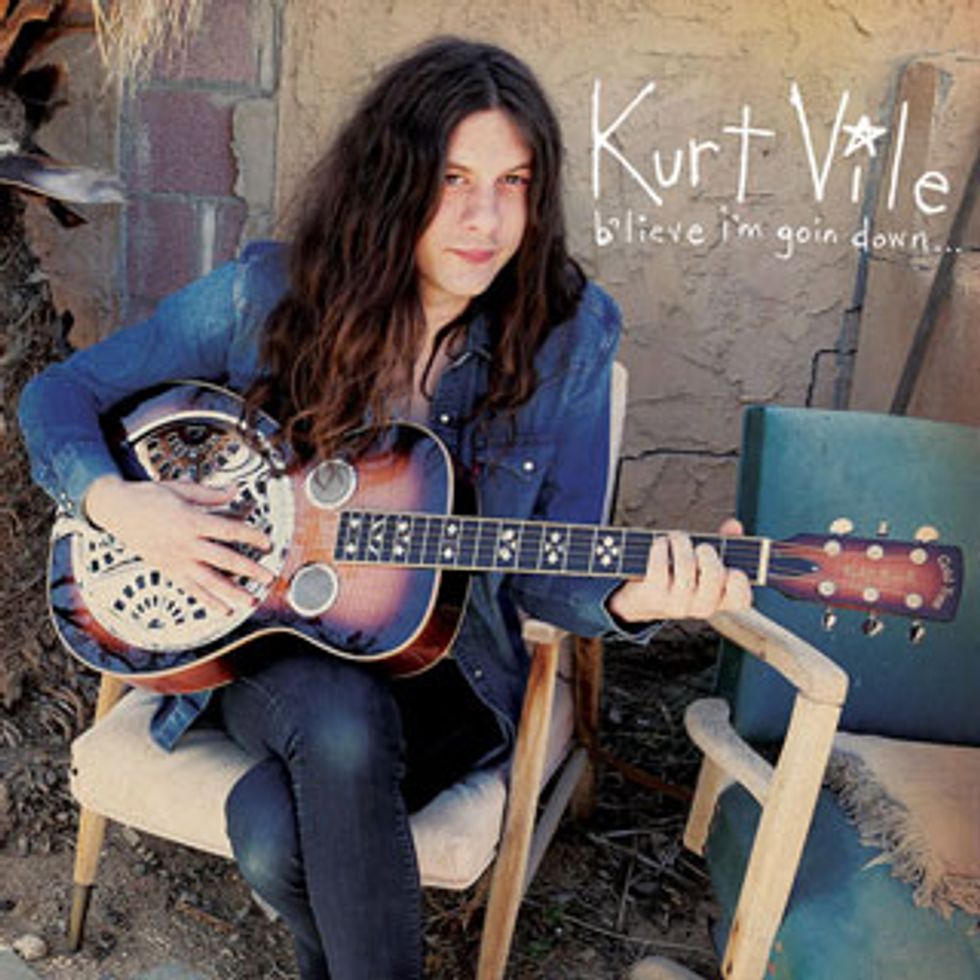

You’re pictured on the cover of b’lieve I’m goin down... with your Gold Tone resonator. How did you record that for “All in a Daze Work”?

Rob Laakso did an amazing job on that one. We recorded at Thump in Brooklyn. I remember coming from a lot of recording on the West Coast, and I had this one phobia where I couldn’t get my guitar in tune, and I think it was really just because I was cranking everything in headphones and it was all amplified. So on that song I basically said, “Screw this. I wrote this song on my couch, and it’s not like I had headphones and all this stuff hooked up.” So I just played it and sang it into the mic live. [See “Keeping It Honest” sidebar.] I did a bunch of takes, but I think we just went with the first or second. We also recorded this whole outro with drums and everything with a melody I added to it, but that didn’t make the official album. Instead that’s the title track on the triple LP edition.

How about “Pretty Pimpin,” recorded with Rob Schnapf—how did that come together in the studio?

I started that on the Dobro, and then I fell in love with an acoustic Rob had at his studio [Mant Sounds in Silver Lake, a neighborhood of Los Angeles]. It’s an old ’50s Gibson, like a ’57 J-45. All of the elements of the song—the bass, the drums, and my guitar and vocals—were sounding great, but once I picked up the J-45, I was just nailing it on the first take, you know? It was just right in the pocket, and Rob was like, “That sounded awesome. Now do it again.” So it’s just two J-45 parts. At one point it had electric guitars, too. Rob handed me this old Telecaster he had, and I don’t often play those. But the song got real definition with the acoustics, and that cool stereo spread. That’s all Rob Schnapf.

You’re also playing the banjo on “I’m an Outlaw.” That part does a lot to define the personality of the song.

Just this past year I got another one from a custom company called Buckeye Banjos. Greg Galbreath makes these amazing handmade banjos, and my friend Nathan Bowles—he plays banjo, but he also plays drums in Steve Gunn’s band [and formerly in the Violators]—has one. There’s like a five-year waiting list to get one of these. Greg makes them for the Avett Brothers and a lot of other people. He basically sold me his personal banjo, I guess because he believed in what I was doing. He’s just such a cool guy, and I believe in him and his banjos, that’s for sure.

YouTube It

Hear a track from Vile’s new album and catch some evocative Los Angeles street scenery. Oh yeah: One of his two ’64 Jaguars gets lots of screen time, too.

“Dust Bunnies” has a great sound to it—almost like it came out of John Lennon’s Imagine era with Phil Spector.

Kyle Spence would appreciate that. That song came out of a slow demo—the first experiment I ever did on Pro Tools, right around the time I’d recorded “I’m an Outlaw” in my space in Philly. And then we tried to do it without any direction whatsoever as a full band version—just blown-out guitars and a drum machine. We realized if we just slowed it down and made it more sloppy, it could work. And conveniently by that point, it was like 5:30 in the morning [laughs], so I just sang and played live again.

Everything about that song is pretty lazy and sleepy, but then the very last thing I did was play those Wurlitzer parts really fast. The idea was just to move really fast, but the feel is about capturing the soulfulness. Often when you do it, you feel like you’re just having fun, and the song is cool, but it’ll take a lot of work when you realize that the looseness—and the words, when they come—gives these tracks real character.

That’s another one of the things I discovered in making this album. Years ago, I’d write a guitar riff, and then write the lyrics, and I’ve got this song. But now, I’ll play one note on a guitar or a piano, and it turns into this melody in my head, and I can hear a million things going on, whereas before it was more one-dimensional. I feel like I can even hear the song before it’s done, with all the chord changes. Part of it’s inspiration and part of it’s memory. If you think too hard, it’ll get cluttered. If you don’t, you can write 10 songs at once at your leisure.

Keeping It Honest

When the red light is on and tape is rolling (or more accurately, when the playhead is moving), it should go without saying that you have to be able to trust your engineer and your producer. To record and mix the entirety of b’lieve I’m goin down..., Kurt Vile worked with eight different people, and yet there’s a seamlessness to the overall sound of the album. Airy and ethereal in some places, blown-out and hard-hitting in others—the record has an identity all its own.“That’s the world I’m trying to get in,” Vile says. “All these things happen to get the sound just right for you—but what happens to me, maybe because I’m sort of a paranoid individual at times, is that once all the official stuff is set up and the light goes on, that’s when I don’t deliver [laughs]. So I’ve got to break down the barriers all the time: ‘Okay, I’m gonna play this song and I’m nervous anyway, so here it goes.’ And then you hear it back, and it’s like, am I singing too soft? I have no idea, but when you have a competent engineer who’s also your bandmate, ultimately it turns out right.”

In this case, he’s referring to Rob Laakso, who became a full-time member of the Violators in 2011, but has known and worked with Vile since his earliest sessions for 2009’s God Is Saying This to You... . Laakso refers to his no-nonsense approach to recording as “honest,” in that the only goal is to capture a performance that’s true-to-life.

“I think a lot of it is probably in what you don’t do,” Laakso explains. “I don’t have any crazy, esoteric miking techniques that I’ve invented, or any secrets that I don’t share. There’s no sound replacement, no Auto-Tune or anything like that. We’ll edit between takes sometimes, but that’s it.”

He takes the recording of Vile’s resonator on “All in a Daze Work” as an example. “We used a Neumann U 67 on it, and there was another condenser on his vocal—maybe a [Neumann] 47 or a 48. I was just going through the instrumentals for the record, and it’s kind of funny. There’s a lot of bleed in my so-called microphone mix on that song, but those two mics give it that sound.

I had them both backed off just to breathe a little bit, but it was a pretty dead room we had set up at Thump in Brooklyn. For the resonator, the 67 was pointed at around where the body joins the neck. We would occasionally adjust that based on the vocal bleed, but if they played nicely together, that’s where we left it.”

On other occasions, Laakso had to rely on instinct—and a travel bag of just-in-case essentials. “One thing was definitely handy for the pitch vibrato that Kurt wanted on the clean guitars,” he recalls. “We weren’t hauling our own amps around, so I was able to cobble together a pretty decent one out of the Eventide ModFactor. I remember at one studio, there was a Watkins Tremolo amp that we were all excited to use, but it made a horrible humming sound and wasn’t working right. Then across the room they had a Gibson stereo tube amp and that wasn’t working right either, so I busted out the Eventide and had a pitch vibrato that made everyone happy. That definitely appears on the record—almost any pitch vibrato you hear on the album, it’s probably that.”

Laakso did the bulk of his engineering and recording at Rancho de la Luna in Joshua Tree, where four of the album’s 12 songs were tracked. “Kurt really liked the atmosphere and the head space of being in Joshua Tree. He knew that before he went out there. He’s never said this explicitly to me, but I’ve noticed he likes to capture a vibe. I don’t like using the word, but that’s what it is, so that’s what I went for. Maybe I’m biased, but when I listen to those songs, I’m definitely taken back to being in that room and that desert air.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)