Luke Temple has such a deep, personal connection to what he sings and writes about that it seems as if he was born doing it. Listen to the electronic-acoustic psychedelia of his band Here We Go Magic, or the avant-garde traditionalism of his solo work, and it becomes quite clear that over the past 10 years or so Temple has matured into the quintessential folk artist of our time. His lonesome falsetto has conjured comparisons to Nick Drake and Jeff Buckley, and his songcraft is weighed against other contemporary masters, including Cass McCombs. Still, musically he nods to Hank Williams and Roger Miller.

Temple’s career in music didn’t start with the concentrated, intuitive focus he possesses today. His current trajectory can be traced back to his freshman year in college. Born in Salem, Massachusetts, Temple initially got into playing with his high school friends when he picked up bass as a teenager, but when he enrolled at Tufts School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, he didn’t have anyone to make music with.

“Bass is an ensemble instrument, for the most part,” he explains. “So I started teaching myself guitar and it just evolved from there.” He even admits he was too shy, initially, to sing. “I had a sense that I could sing,” he recalls. “But, like guitar, I started because it is something you can do by yourself.” He also developed a keen compositional perspective as a painter at Tufts that he would eventually apply to songwriting. Even his deft fingerpicked licks seem to resonate from the pattern-oriented headspace he discovered in college. “My natural inclination,” he says, “was to figure out patterns [on guitar] and then write little songs from those ideas.”

After Tufts, and struggling to make it as a visual artist, Temple recorded two folk albums under his own name, Hold a Match for a Gasoline World (2005) and Snowbeast (2007), before forming the New York-based indie-rock band Here We Go Magic in 2008. Their eponymous debut was released the next year. It was recorded almost entirely alone by Temple on a simple 4-track recorder with nothing more than a drum, one microphone, a synth, and an acoustic guitar. Here We Go Magic eventually morphed into a five-piece, gaining critical acclaim for The January EP (2011) and A Different Ship (2012). But whether working with a band or alone, Temple seems to prefer a songwriting palette that blends stream-of-conscious lyrics and melodies with groove-inflected bedroom folk music.

On A Hand Through the Cellar Door, Temple’s latest album, this auricular template once again manifests itself in quirky, compelling songs. Musically, the set is a whimsical expression of minimalism featuring the trio of Temple on guitar and vocals, Ben Davis on bass, and Austin Vaughn on drums. Lyrically, Temple’s meditations on life take the listener inside the head of someone seemingly immersed within his own thoughts. On “Birds of Late December,” Temple traverses a memory he has about his parents’ divorce, while his gently twined vocal and guitar melody evokes Elizabeth Cotten’s “Freight Train.” In “The Case of Lewis Warren,” Temple sings about a former high school classmate as he channels the ’70s folk-crooner vibe of Fred Neil and Tim Hardin. “Smashing Glass” touches on the destructive aspects of anger in its lyrics, and Temple’s fluttering, nimble fingerpicking sonically paints an Eric Fischl-like figurative image. Reminiscences such as these abound on A Hand Through the Cellar Door, set in relief by the role space plays in the songs’ minimalist arrangements.

The symbiotic relationship between influence and expression in Temple’s songs illuminates an organic approach that is both familiar and refreshingly original. His storytelling demonstrates an inimitable intuition for the fascinatingly askew. And his guitar playing skips and hiccups unpredictably and effortlessly within the sparse soundscapes he creates as a backdrop for musical and personal nostalgia. Yet his trips down Memory Lane are never sappy.

PG recently caught up with Temple at his adopted home in Los Angeles to discuss the influence of musical traditions, the illusion of space in music, the cathartic aspects of songwriting, his artistic evolution, and his unpretentious oddball gear.

When you first picked up an instrument, was the catalyst to write your own songs or learn cover songs?

I always wanted to write my own music. I started just jamming with friends and improvising. We never really learned covers, even back then in high school. I always felt like it was much cooler to write my own material. Maybe it was my compositional brain coming from painting. Now, in retrospect, I wish I had come up learning more covers and, at this point, I’m interested in going back and learning more covers.

FACTOID: An element of A Hand Through the Cellar Door’s seductive sound is bleed. The album was recorded live with minimal miking, including a Telefunken U47 for vocals that also picked up Temple’s nylon-string guitar.

Why?

I think there’s strength in tradition. Whether I realize it or not, there’s always some attempt to avoid clichés—little songwriting tropes—as a songwriter. But inevitably I’m influenced. Like the 12-bar progression, for instance. There’s always room for that. It could be considered a cliché, but there’s always a different way to reinterpret that. And right there I’m being influenced by American songwriting via Scotch-Irish music that goes way back. Whether or not you’re learning covers you’re still influenced by the lineage of music that predates you. Actually going in and learning covers and different forms probably enriches your palette.

You have a strong, educated background in painting. Does that ever cross over or influence your music?

I don’t think about them both at the same time. But I’m probably utilizing the same part of my brain. There are similar considerations with regard to composition and bookending narratives and things like that. Whether it’s visual or auditory, it comes in and is processed by the brain in the same way. It goes into the darkness and then it is just information. There are a lot of similar considerations writing a record and working on a painting.

What is your songwriting process?

It usually starts off with throwing shit at the wall and then editing out the parts that don’t work and finding the narrative thread in there. It starts from a more subconscious place. Or I’ll have an idea about what I want to write about, but then I just let that spring up from the subconscious. If I don’t try to be too literal about it, it eventually just sort of shows itself. And then the rational brain takes over and you have to roll up your sleeves and get into the editing part. That’s always the hardest part for me, but it’s really important.

Why do you find that’s so hard?

Because part of me wants every tiny little pearl and jewel in there, and every little metaphor, but you have to remember not to try to impress too much and just get the idea across—the story. To get stuck in minutia can be a trap.

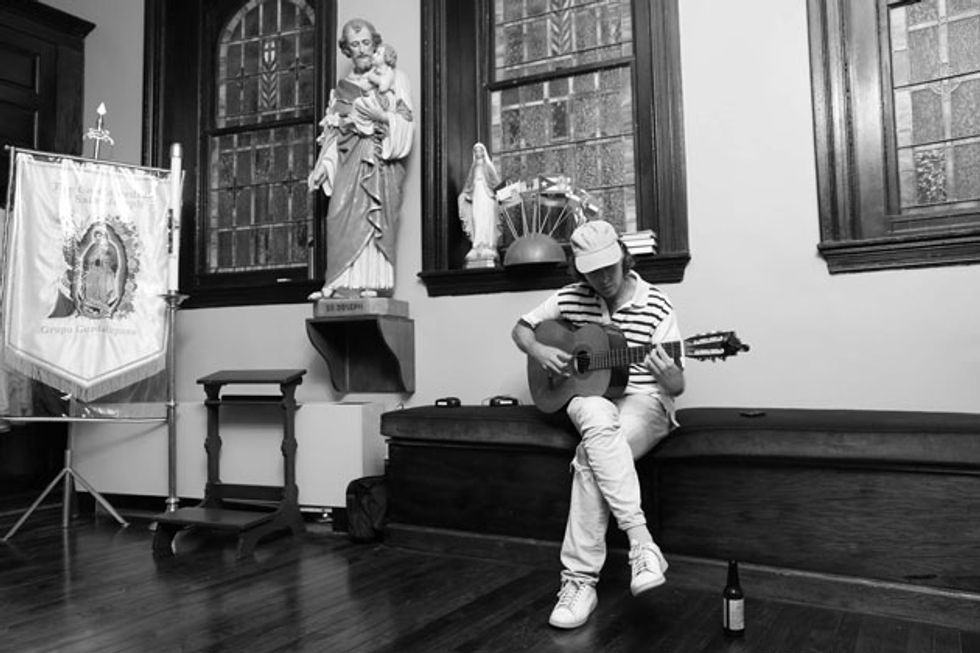

Luke Temple, warming up on his Guitarras Madrigal Modelo 98C nylon string before a November 2016 performance at the Co-Cathedral of St. Joseph in Brooklyn, pursues songwriting via inspiration and perspiration. He says he lets songs begin from a “subconscious place,” and then rolls up his sleeves. Photo by Taylor Swaim

Many of your lyrics seem to be personal tales.

There are two songs on the record, “Maryann Was Quiet” and “The Case of Lewis Warren,” that are about people I actually know. Those are true stories. Usually I start with something that I’ve been through and I have an idea about what I want to write about, but then I have to turn off my rational brain to allow the images to pop through. Just think about the situation, then free associate, and then edit it slowly together.

Do you apply the same approach to the musical components of your songs?

That’s the most intuitive part, and that usually comes first. “Maryann” started with lyrics, which is pretty rare for me. Usually it starts with the music, like some sort of rhythmic feel that I want to use, then the music, and then the lyrics.

What were you thinking, conceptually, about “Maryann Was Quiet?”

Musically I was thinking Velvet Underground. There are so many lyrics and it’s very conversational, so it seemed ridiculous to make the music too baroque or too modal. The music just needed to be really simple to tell that story.

I hear some interesting influences in “Estimated World.” Where does the rhythmic figure come from?

I was listening to some North African music, if I remember correctly, like Tuareg stuff. There’s a little guitar line in the middle of the song that is a Tuareg rip-off, in my mind, but the vocal delivery is maybe [composer] Arthur Russell, a little bit. That song is less narrative than the others. The title says it all. We’re always estimating and going on statistics, but we really have no idea what’s going to happen. That song is more about the groove—going from E to F#, back and forth. I was also thinking “Fire on the Mountain” by the Grateful Dead, which is just A to G over and over again. A lot of Talking Heads songs have that whole-step movement. It’s an easy progression to float over. I also really like holding a whole-step above in the bass while the other chordal instruments move down a whole-step, like keeping an A over a G. I think that’s a beautiful sound. That was the vibe of that song.

Tell me about the band and the recording process. The record has a real live vibe to it.

It’s just a trio—Ben Davis on bass and Austin Vaughn on drums—and we recorded it in two days. We did a bunch of rehearsing and then went into the studio and recorded it live. Everything is live. There are a couple of overdubs here and there, but the bulk of it—the vocals, bass and drums—were all done together.

playing really intuitively.

Did you write what they played or did they come up with their own parts?

I’m with Miles Davis, in that it’s not about writing parts for people. It’s about picking the right people. If you pick the right people, they are going to play stuff that works. You have to start there and let them be themselves. If they are the right musicians they are going to understand the tone. They’re going to know it needs to be sparse, or whatever kind of thing you’re working with. Those guys were the right fit for this particular batch of songs. And they loved rehearsing so there was no twisting their ears to go in and work on the songs.

There’s sparseness to the music that must be challenging to capture convincingly. You have to be loose, but tight.

The music is pretty simple, so it might seem like I just showed them the song and they just came up with the first thing on their minds, but it was a lot of work, actually. To work with such a simple palette like that, it’s like less is more. The more space you utilize the more you actually hear—the fuller it seems. It’s like this weird illusion you can create with space and that takes a lot of work. At least it did for this record.

How do you balance over- and under-rehearsing for such a session?

The first time you show something to a band, the vibe is sort of perfect because everyone is on their toes. They don’t really know what’s coming, and they are playing really intuitively. But usually people hit wrong notes or make mistakes because they don’t really understand the song—especially if it’s a bit more complex. My songs usually have little turns that no one would really be able to predict intuitively. There are certain songwriters, like Bob Dylan for instance, who would just come in and show the song to the band right there and they would be hanging on for dear life. You can hear that in a lot of his recordings.

Blood on the Tracks was reportedly done that way—at least partially.

And I feel like you can hear it. You can hear the bassist just listening or looking at Dylan’s fingers for when they’re going to change. And that adds real electricity to a recording. With a lot of my songs, you couldn’t really do that because they’re a bit more baroque in the way that they are written, so there needs to be some rehearsing.

How would you describe the phases of development in the rehearsal process?

At the beginning, the vibe is right, but inevitably there’s going to be some kinks to work out. And then there’s this whole middle period where everyone basically figures out what they want to play, but it starts to get really uptight because they are thinking about it too much. And then it gets to a point where—and maybe you’ve played it live a few times—you actually transcend that and you get back to the innocence of knowing the song so well you can relax in it and just have fun with it. And you can kind of improvise again within the parts that you’ve written for yourself. I knew it was time to record when everyone had the songs under their belts completely and we could just play with it. It’s a whole process.

Inside Temple’s Gear Sanctum

Some players subscribe to the guitar-as-hammer-and-nails philosophy—the notion that the instruments so many of us drool over are simply tools for getting a job done. Luke Temple is one of them. Despite his sonic conjuring, he says his needs are basic and he makes the most out of whatever is at his disposal, to the extent that he sometimes doesn’t remember what he’s actually used to record.

On A Hand Through the Cellar Door, Temple says he played a Guitarras Madrigal Modelo 98C nylon string that he says is on permanent loan from a friend. At home he plays and writes on an inexpensive Yamaha FG-30 12-string acoustic that is nowhere to be heard on the album. With Here We Go Magic, he relies on his trusty, well-worn 1965 Valco-made National N-644 solidbody, which is also absent from Cellar Door.

The sole amp he used on the album is a small Vox that was provided by the studio where he cut Cellar Door. He admits he doesn’t remember the amp model, or the make of the contact mic he used to translate his Madrigal 98C’s vibrations to it. Temple's own go-to amp for live shows, a Fender Concert Pro, was recently stolen. And while he doesn’t declare a preference for any particular brand of strings, he does use .011 sets on his nylon-string and 12-string guitars. He does not use a pick.

Temple explains that his well-played nylon-string Guitarras Madrigal is on “permanent loan” from a friend. It’s also all over A Hand Through the Cellar Door.

Photo by Taylor Swaim

You have to have structure to break free from. Even most jazz musicians are improvising over chord changes.

I always think of someone like John Coltrane. These master musicians practiced probably 10 or 13 hours a day in such a formal way that they just broke through some other side. His ascension on those records, from A Love Supreme on—it’s just this completely free music. In a sense, rehearsing for a record is a little microcosm of that. You want to get to the point where you’re free past the form, but it’s not like my music is free music.

You only play acoustic guitar on this record. How did you track your instrument?

We miked it and also had a contact mic going through an amp. I think it was a small Vox that was blown out a little. I don’t think we used much of that track other than to beef it up or give it a little grit occasionally. For the most part we used the guitar mic. I sang through a Telefunken U47, and that invariably picked up a bunch of guitar, also.

Did that kind of bleed cause mixing issues?

Nowadays when you mix and master a record you do a vocal version and a non-vocal version, because if you hope to sync your music to a commercial or a film, everyone always wants the instrumental version. And that was the one thing about this record I couldn’t do, because everything is bleeding into everything else. There’s no way of taking out the vocal without taking out the guitar. Or the vocal was in the guitar track. It just was impossible.

Do you prefer acoustic or electric guitar?

In Here We Go Magic I play electric, but I think I prefer playing acoustic. It’s the instrument that I write all my music on, mostly because I write at home. I actually have a 12-string I like to play a lot when I’m kicking around the house.

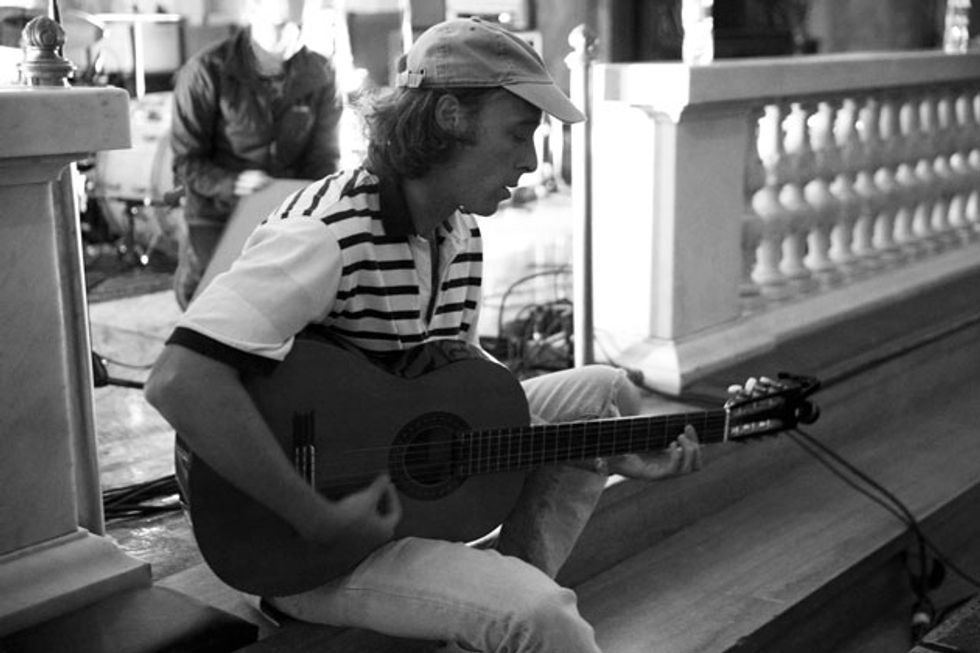

Bass was Temple’s first instrument, but when he found himself without playing partners in art school, he began to explore acoustic guitar and singing, which put him on his current path.

Photo by Taylor Swaim

You’ve done albums at home by yourself on a 4-track and in a studio with a band. Do you have a preference?

They both have their place. I’m recording right now by myself. I love working alone and just being in a world of overdubs where I play everything. But there’s something you can’t get with overdubbing that you can capture live with other human beings. It’s just a case-by-case situation that depends on the song. The more narrative songs would feel weird for me to labor over. This record needed to be conversational, so playing live with other people gives it that vibe.

Is there anything cathartic about the writing process for you?

My insides are a big jumble and my mind is constantly going. I’m constantly thinking about the next thing, so it’s hard for me to reflect and say whether something is cathartic or that I’ve worked through a problem. I’m just always on to the next thing.

But it feels that way when I perform. Writing feels like a lot of work. There’s a certain satisfaction when you finish a song, but it’s not always enjoyable, necessarily. I love doing it and I understand that I have to do it every day. I’m writing all day, every day. But it doesn’t feel cathartic until it’s finished and I perform it or record it really well and I listen back. Then it feels like a success.

YouTube It

Luke Temple’s belief in keeping things sweet and simple resonates through this solo performance of Here We Go Magic’s “Miracle of Mary” on his nylon-string guitar, recorded at the Vondel Hotel in Amsterdam in 2012.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)