King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard, a seven-piece band from Melbourne, Australia, is nothing if not ambitious. They released eight full-length albums between 2012 and 2016, have toured the world multiple times, and, for 2017, announced five more albums. “Sometimes I regret that I said that,” guitarist and lead singer Stu Mackenzie says. “I hope we can do that.”

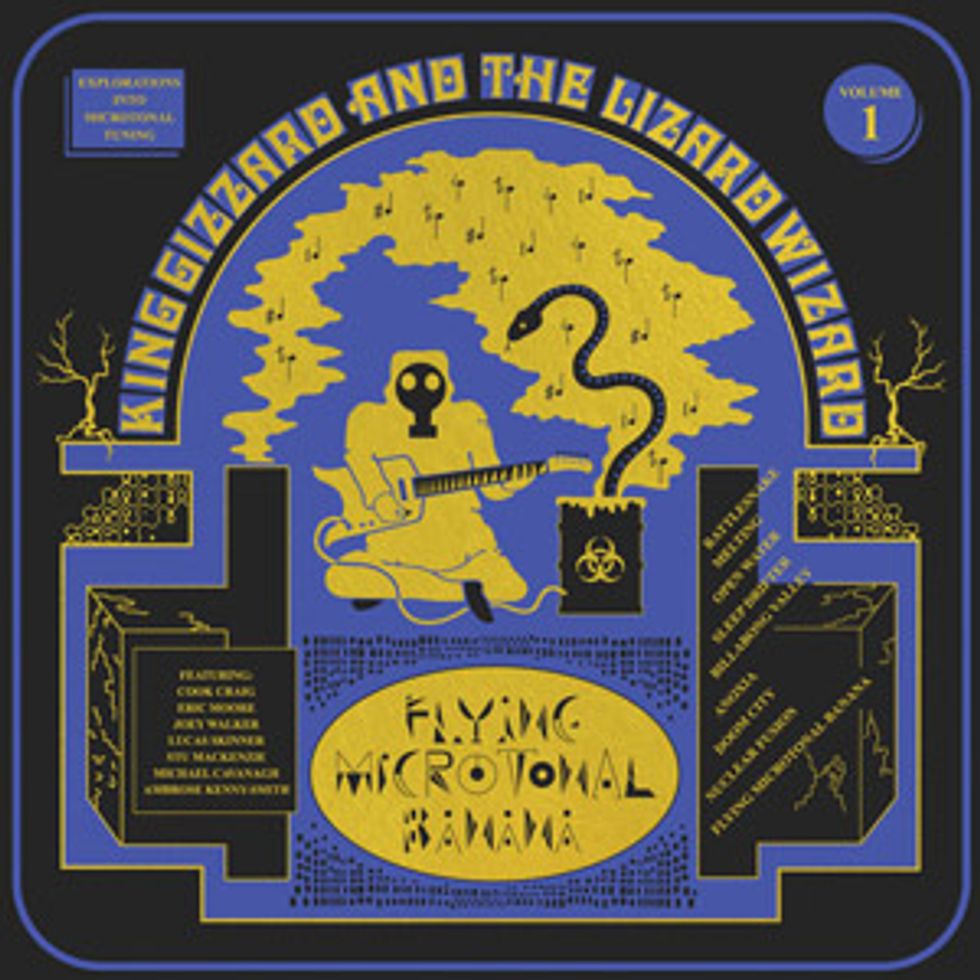

The first of the five, Flying Microtonal Banana, came out in February. As the title implies, the album explores microtonal music. To play microtones, most of the band members had their instruments modified. These mods include adding extra frets to guitars and basses, re-pitching vintage keyboards, and even altering a harmonica.

“It’s actually not so hard to modify a harmonica because you can pitch the reeds,” Mackenzie says. “We also modified a DX7, an old ’80s Yamaha keyboard, which is easy to pitch the notes individually on. We had quite a few microtonal instruments in the end.”

For King Gizzard, microtones are just the tip of the creative iceberg. “The second release is going to be the weirdest record we’ve ever made,” Mackenzie says. “It’s very narrative-driven and a lot of the story is narrated throughout.” That’s to be followed by a collaboration with Mild High Club’s Alex Brettin. And then? “I don’t know,” he replies. “We’ve got three albums happening. Four and five are too futuristic to think about at this point.”

Ambitious projects, a schizophrenic approach to album making, and doing things differently are what the band is about. Their line-up includes three guitarists and two drummers (plus bass, keys, and, obviously, harmonica). Their discography includes Quarters!, a 2015 release comprising four songs that each last exactly 10 minutes and 10 seconds; Paper Mâché Dream Balloon, the same year’s collection of short, acoustic, psychedelic songs; and Nonagon Infinity, 2016’s thematic and infinitely looping album. They play garage, intricate prog, free-form improv, noise, and pop. Pick your favorite label—it probably fits.

That eclectic nature also applies to their choice in gear. Their amps—Fender Hot Rod DeVilles and a Roland JC-120—may be standard fare, but for guitars they prefer ’60s Yamahas, custom creations from Melbourne-area luthier Zac Eccles, and a Hagstrom 12-string, among others. “I bought a new guitar last week, which I am excited about,” guitarist Joey Walker says. “It is a 1965 short-scale jazz guitar—a Burns London. It might be making its appearance fairly soon onstage.”

King Gizzard’s tastes are diverse—or better, eccentric—and that could prove distracting. But while the band is very much a collaborative effort, they aren’t leaderless, and Mackenzie is the ensemble’s ringleader. “Stu would be like the project manager,” Walker says. “He provides a lot of ideas. Everyone in Gizzard is a great musician in his own right and there are heaps of ideas from everyone, but having a leader has been very important to our cause.”

We spoke with Mackenzie about that cause. We also talked about managing a large ensemble, modding guitars to make them microtonal, songwriting and improvisation, and the importance of setting goals before composing an album. And we spoke with Walker (see accompanying sidebar) to get his take on these topics as well.

King Gizzard has three guitar players. Why is that and how do you keep from stepping on each other’s toes?

In a lot of ways, it is an accidental band. Early on, when the band was forming, we were all playing in other bands. This was a project we put together with no pressure. It was just supposed to be fun, super-lighthearted, and early on it was a completely improvised thing. It wasn’t improvised in the sense like the Grateful Dead. It was improvised in that we had songs that had one chord, one word, and whoever was around—sometimes it would be three people, sometimes it would be 10—and we would bash away on that one chord for however long it felt right. Just scream and go psycho. It was this chaos, clusterfuck thing. The seven people we have now are the seven who stuck around. That’s why we have such a bizarre line-up. We were all friends before this band. It was never supposed to last this long. It somehow took over.

The first album King Gizzard recorded to tape, Flying Microtonal Banana was tracked in the band’s studio on a simple 1/2-inch 8-track Tascam.

It sounds like the guitar parts are very worked out.

That’s true now. I am going back to 2010 to 2011. It took us a few years to work out how to play with three guitars. As you said, it’s tricky to not step on each other’s toes. I guess I started thinking in threes in terms of arranging guitar parts. You can often have one guitar sitting in the pocket and have two sitting on top. You can get some cool sounds like that.

Do you purposefully use different instruments and amps to distinguish your tones?

I don’t think that’s something we’ve ever actively thought about. At the moment, we all play pretty different instruments. I am primarily playing 12-string. The other guys are playing 6-strings, but again, they’re different. Joe [Walker] and I both use pretty standard amps: Fender DeVilles. Cook [Craig] usually has a Roland JC-120 these days. That’s a good question. Maybe it’s something we should think about more? [Laughs.]

Thinking in threes, what are some of the things you’ll do when arranging guitar parts?

A lot of time the music is pretty noisy and pretty messy. All three of us are chugging on the same chord. Or all three of us are doing high, noisy melodic stuff at the same time.

You don’t do much traditional soloing.

I don’t know if that’s deliberate or if that’s just what we’re drawn to. There are some guitar solos in all the music we’ve recorded, but not very many. It’s never been something I’ve been particularly drawn to. I feel like that has already been nailed. There have already been so many amazing electric guitarists, it’s hard to think, “I want to put my stamp on that.” I think they probably nailed it in the late ’60s—that’s a long time ago now. When you think about it, it’s funny to have a band with three guitarists and not really do very many guitar solos.

What was your introduction to microtones?

I have a few unusual, especially Middle Eastern, instruments around. I have a setar, which is a Persian instrument with a skinny neck. [Editor’s note: The Persian setar is a different instrument from the Indian sitar.] It has moveable frets. I have a bağlama, which is really cool, and I’ve played that a lot. It is Turkish and has movable frets, too. I guess the two instruments are fairly related on the musical family tree.

In a lot of different musics not originating in Europe, the tonality can shift—even from piece to piece. Not in the sense that we’re used to, where it goes from major to minor or from one key signature to another, but the actual arrangements of the notes—where they’re placed or where the frets are—can change. I based the fret arrangement of my Flying Banana guitar on a bağlama, though not exactly. A bağlama isn’t exactly 12 tones per octave, or even 24 tones per octave. It’s got a lot of “in-between” notes and a lot of different flavors and sounds. I stuck to 12 notes per octave and just added a few quarter tones. It was easier to modify the fretboard that way. Also, it felt like it would be easier to play with instruments I was used to. I’m lucky enough to have a friend who is a guitar maker. He said, “I’m going to build you a guitar. Let’s work on something together.” I was like, “Sweet. I’ve got this idea. Let’s do this microtonal thing.”

The ignition point for the band’s new album, Stu Mackenzie’s microtonal Flying Banana guitar is equipped with extra frets and tuned (low to high) C#–F#–C#–F#–B–E. Photo by Matt Condon

So the guitar has a standard fretboard with some quarter tones thrown in?

You got it. It probably averages a quarter tone every second tone and it is arranged in a way that makes sense to play the quarter tones that I wanted. If I were to do quarter tones over the entire neck, it would make the guitar look too confusing, as if I was playing a different instrument. I’ve got a Strat at home that is completely quarter tones all the way up. It is much, much harder to play. I play the Banana guitar in a half-open tuning that’s similar to the bağlama. Low to high, it’s C#–F#–C#–F#–B–E.

The whole band got their frets adjusted like that, too?

Yeah we did. That guitar was the original. I was playing it for about six months or a year or so—that’s where all these tunes came from. When it felt like, “Maybe there is a record worth of songs here,” I said to the other guys, “Do you each want to potentially ruin a guitar?” I said to buy really cheap guitars and get them modified. We ended up with three modified electric guitars, a bass guitar, and a harmonica.

Getting a fretless guitar wasn’t an option?

A fretless guitar would have been cool, but we didn’t have one when we made this record. It was something we talked about—especially a fretless bass. I think Cook actually bought one, but that was just after we made this record.

A lot of your music is in odd meters. Is that on purpose or do the riffs just come out that way?

I think a little of both. Some of our earlier recordings are pretty much all 4/4. But there are a handful of songs—or parts of songs—that went into other meters. They were kind of accidental. The first time I remember doing a song in an odd meter with King Gizzard was “Float Along - Fill Your Lungs,” which is off our third record. It’s all in five. It’s got a long count five and a short count five layered on top of each other, which is the way I count it. When we were making that song, it was based off this riff that, to me, was really intuitive, but when trying to relay it to everyone it became completely convoluted and confusing. I guess that is the nature of playing in odd meters. It was a pretty tricky song for us to record at the time, but once you get the bug for it, it becomes more second nature. Sometimes you’re thinking, “Maybe we should try something in some odd meter.” But most of the time when you have an idea for a melody or a rhythm in an odd meter, you don’t realize it’s in an odd meter.

So it is organic?

Yeah. It’s a funny thing: 4/4 is great and definitely has a place, of course, but once you start diving into the odd meters, it can be pretty addictive. It’s almost like it seeps into your consciousness.

You mentioned the tuning on your Banana guitar. Do you try other tunings as well?

Yeah, sure. The Banana is tuned to a semi-open thing. Going back to “Float Along - Fill Your Lungs,” that was in a funny tuning. I wish I could remember what that was, but I had two strings in a row that were the same note and one of them was super floppy and you could do these wild bends on it. I don’t remember what it was anymore, but it was an open tuning and it was all firsts and fifths. It had more of a droning thing to it. My 12-string is almost always in standard, and my other guitars are in something else.

Stu Mackenzie’s Gear

GuitarsHagstrom F12 12-string

1967 Yamaha SVG800 Flying Samurai

Flying Banana Microtonal Guitar built by Zac Eccles

Amp

Fender Hot Rod DeVille

Effects

Boss TU-2 Tuner

MXR Carbon Copy

Boss DD-3 Digital Delay

Dunlop Cry Baby Wah Wah

Devi Ever Torn’s Peaker

Strings and Picks

.011 sets, any brand, for 6-strings

.010 sets, any brand, for 12-string

Dunlop Nylon Standard .88 mm

What type of guitar is your 12-string?

It’s a Hagstrom F12 from 1966. That’s my main regularly fretted guitar at the moment and has

been for a while. That is the guitar on

Nonagon Infinity and anything since then. I love it and hate it at the same time.

How so?

It’s got really high output and the pickups are microphonic, so I pick up a lot of noise. You can yell into them and it will come through the amp. They can be really cool or really terrible with high gain and distortion because you get so much outside sound coming into them. But that also makes for really interesting sounds that you can’t do otherwise. I had a small pickup fitted into the middle position. I thought I would use it all the time when we were delving into higher-gain stuff, but I never use it. The original ones sound way better.

I noticed that live—maybe it’s because of those pickups—you hold that guitar over your head, point it at the amp, and get instant raging feedback.

I like to have the amp fairly close to me. I play off it a fair bit. It is the kind of guitar that if you stand a certain way, it will take off. That may be unusual because it is a fairly light, not hollow, very solid guitar. But I guess it is the nature of those pickups.

How do you approach the studio?

The recording process has been part of the creative process as well. We’ve done it a lot of different ways. When making Flying Microtonal Banana, we got a little space in Melbourne. This was the first record that we properly made ourselves with all our own gear and my little 8-track tape recorder—that was cool. It was basically everyone in one room pointing toward each other. The studio is one rectangular room. There is a desk with the tape machine and the techy stuff on one side, and we set up on the other side of the room. We had a couple of baffles that are on wheels and we separated things a little bit.

Part of the process with this album was that the songs weren’t overly rehearsed. Of the nine tracks, seven came together this way: I would have a semi-structured idea for a song with a bunch of parts—probably some vocal ideas, but not all of them. Then we would get together in the morning and I would go over it with everyone. We would jam on it for most of the day, it would probably change a lot from the original idea, and by the afternoon we would roll the tape and have the take. It was a good loose way of capturing the vibe. There is always a magical vibe when you first nail the song and that was what we were going for with this one.

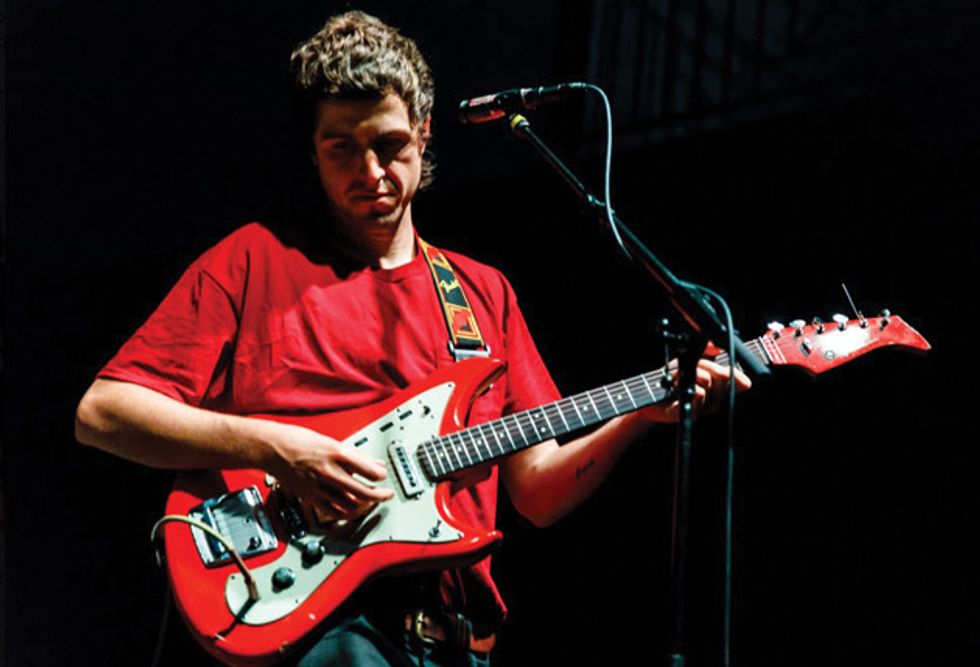

The seven-piece King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard strikes a careful balance within its triple-guitar pandemonium, with Stu Mackenzie (shown here assaulting his Hagstrom electric 12), Joey Walker, and Cook Craig artfully and

intuitively layering riffs and tones. Photo by Matt Condon

You recorded to tape? No Pro Tools?

This one we did to tape, which is just a half-inch machine and very un-fancy. It is a little Tascam machine. It went into the computer after that and we did some digital overdubs. But the main tracks were recorded to tape, which is interesting—doing seven people to eight tracks.

Do you just use your live gear or do you experiment with different amps and guitars in the studio?

We definitely are experimenting. For Flying Microtonal Banana, I just used one pedal, which was a wah. Live, I have a few more. I like the idea of having a simpler setup—especially having a drier amp, no reverb, and no delay. There is a little bit of that added in the post stuff. We are not using a whole heap of wild effects. We’ve got pretty small pedalboards and we use fairly stock standard amps—nothing that anybody couldn’t do.

You guys embrace challenges and that’s part of what makes the band so fun.

I’ve always been drawn to making records in general. I love recording and mixing. I like the whole process. Working with the other guys in the band—that’s what I am drawn to, the collaboration element. Playing live is amazing and I love that, too, but I’ve always been first and foremost drawn to making records. And I’ve always wanted to have a reason to make a record. It never made that much sense to make the same record over and over again—although AC/DC did that and they did that fairly well, so maybe there is a time and place for it. But we’ve never wanted to do that. Every record we’ve made has been for a reason, or at least to challenge ourselves, or to try something that we’ve never done before. Every record has some kind of conceptual thing attached to it. Often it’s something really simple that is challenging to us. I find it a lot easier to make music if I have a vague understanding of the destination.

Meaning an overall goal and not just a collection of songs?

If we just wrote whatever songs and recorded them, I think our music might have been a bit more straight. Maybe not … it’s hard to say. Some people have the mindset that the human brain is this magical place. That you should have respect for it and do what comes out of it or do what comes out of your emotional state. But I look at it more from the point of view of the architect or the painter. He knows what he’s painting. He’s not just getting a bunch of colors, closing his eyes, and slapping them on the canvas—though some people do that, too.

YouTube It

King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard invite you into their studio for some rock ’n’ roll show-and-tell, providing a close-up look at Stu Mackenzie’s Flying Banana microtonal guitar, Joey Walker’s custom T-style Thinline, and Lucas Skinner’s modified bass. Note the extra frets on each of these instruments and hear the melodic mayhem they generate.

“We got the wah-wah pedals to make our fuzzed-out guitar solos be more wild and more all over the place,” says Joey Walker, one of King Gizzard’s three guitarists, “but I quickly realized there is so much more you can do with it.” Photo by Matt Condon

With three guitarists in King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard, the onus is on each player to keep things under control while maintaining some semblance of sonic identity. “I have my wah pedal on the whole time during a set,” guitarist Joey Walker says about how he distinguishes his tone. “I roll off tone or find color within my tone, judging by how forward or far back my wah pedal is. I also like to get a constant oscillating thing going, which is quick vibrations on the wah pedal. We got the wah-wah pedals to make our fuzzed-out guitar solos be more wild and more all over the place, but I quickly realized there is so much more you can do with it. I love the control it gives me.”

Joey Walker’s Gear

Guitars1965 Yamaha SG-3

Godin Richmond Dorchester

1965 Burns London

Modified T-style Thinline copy (for microtones)

Amp

Fender Hot Rod DeVille

Effects

ZVEX Fuzz Factory

Wampler Faux Analog Delay

JHS SuperBolt

Jim Dunlop Jimi Hendrix Signature Wah

Strings and Picks

D’Addario XL sets (.011–.046)

Dunlop Nylon Max Grip .60 mm

The guitarists also vary their amp choices, though those differences are subtle. “Cookie uses a Roland JC-120,” Walker says about co-guitarist Cook Craig. “He likes having that bright, really clean tone.” Stu Mackenzie and Walker both use Fender Hot Rod DeVilles. “Stu’s is different in that he has it on the overdrive setting,” Walker says. “I have it on the clean channel, but that’s because I have an overdrive pedal and Stu doesn’t.”

Carving out distinctive tones is one part of the puzzle; when and how to improvise is another. “Our first records were more garage rock, three-chord songs,” Walker says. “Then we started getting weirder. We’d set a framework for the jam, but often that would be at the expense of the audience. Sometimes we’d get it right and it would work, but other times it would be a bit flat. We realized that when we were writing and trying to explore a song, improvisation would be the most important element to it. But now we set the structure in stone when we play it live. There are a lot of people on stage and we don’t want to step on each other’s feet. But we’ve recently spoken about how we miss that improvisatory element. We might start incorporating that into our live show again, because it was so much fun.”

And if managing a large, improvising ensemble wasn’t enough, the band is also exploring microtones. “Stu bought a bağlama, which is a Turkish type of lute with movable microtonal frets,” Walker says. Zac Eccles, a Melbourne-based guitar builder and friend of the band, built Mackenzie’s yellow microtonal Banana guitar. “Stu had been mucking around with his Banana guitar for a while and had come up with these ideas. We were like, ‘Maybe we should build an album around it.’ Cookie, Lucas Skinner—our bass player—and I went out and bought some fairly low-quality guitars. Zac put some extra frets on and it ended up being really cool. It reinvigorated my interest in guitar to a certain extent, because it was another avenue to go down.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)