It's not easy to maintain a 40-year career in the underground, let alone one that's remained both highly influential and continuously creative, innovative, and satisfying. Yet Thurston Moore is back with a formidable new album, Rock n Roll Consciousness. Within his many years in Sonic Youth and beyond, Thurston has used the roots of rock 'n' roll in a way that bends the light into a kaleidoscopic mixture of post-punk awareness, psychedelia, noise, and composition.

Rock n Roll Consciousness touches upon styles that have been prevalent throughout Thurston's career. The album's opening track, “Exalted," cooks up a delicious stew of guitars that touch upon '70s rock and skronky free noise, matched by a groove that would easily fit within a Sonic Youth record (no surprise, as Sonic Youth drummer Steve Shelley is back behind the kit). “Cusp" plays out in a long jam that brings to mind the sprawling sections of Sonic Youth's seminal Daydream Nation.

“Aphrodite" recalls the edgy, angular “no wave"-influenced sound of the early '80s. Moore's been working with the same group of musicians since his 2014 solo album, The Best Day. Besides Moore and Shelley on drums, the quartet includes English guitarist James Sedwards on lead guitar and the rock-solid Debbie Googe, longtime bassist for the legendary My Bloody Valentine.

“You should interview James [Sedwards]—he's the real guitar player. I'm just the composer!" was Thurston's opening remark during our in-person conversation backstage at the Constellation Room in Santa Ana, California. Moore was open and candid, looking deeply at his rock roots and the musical journey he's embarked on since moving to New York City smack dab in the middle of the late-'70s punk scene. Sedwards, a phenomenally tasteful, brilliant guitarist in his own right, sat in and provided crucial information regarding the band's recording process and gear.

I hear a lot of '70s rock influences on the new album, in a really good way.

James Sedwards: [Laughs.] There can't be a bad way.

It's a West Coast-sounding, groovy kind of lead guitar style, especially. Do you ever think about that aspect of it, or am I way off base?

Sedwards: I didn't, no. It was certainly not thought out. The material was recorded and developed so fast, there wasn't much time to consider it a great deal.

Moore: I don't think there was purposeful reference to '70s guitar leads. I'm not speaking for James, but it's not like we reference that kind of playing the way, say, Black Crowes would reference it or something. Nothing against the Black Crowes, they're very tasteful in their referential playing. It just happens in the moment.

I'd never really seen James play, until he played with me. When I wanted to start developing a band, I asked James if he wanted to be involved with the beginning of it. Which was just two guitars playing instrumentally with some compositions I had. Just knowing through our discussions what he was interested in, which ran the whole gamut of Teenage Jesus and the Jerks to Led Zeppelin.

That, to me, showed we're really in the same ballpark. So, I showed him some of my rudimentary minimalist chord structures and the only real challenge was putting your brain in this place where the playing is not standard tuning. Which he picked up immediately because he had a realization of what those tunings were, through his interest in Sonic Youth, Glenn Branca, My Bloody Valentine, and Velvet Underground.

When we did The Best Day, the first album with those first songs, I realized as we recorded it and right afterwards that I didn't really tap into James' technique as a lead guitar player so much. I knew it was there. I think it was during the sessions, I said, “I'm going to start playing the lead on one of these songs," and then I realized, “Oh."

Secret weapon. I knew that the next songwriting bout, I would want to make room for that kind of expression as far as James is concerned. Because I certainly don't play with that technique. I never have. It's not that I wouldn't want to. I just never got studious with it. Generally, I like that it's completely unorthodox from my playing as far as how I approach it, lead-wise. My leads are usually free-noise based.

“I wanted to take the guitar sounds I really liked but do something else with them so they were this raging thing that was almost an artful heavy-metal thing, without the corniness of heavy metal." —Thurston Moore

I was listening to Gábor Szabó last night and drew some comparison to your leads.

Moore: My leads? Maybe some picking concepts could be considered Gábor-style. I mean, he's incredible, of course. When I think of the dexterity of Gábor Szabó, I think James could come close. He's much more studious with his version of the guitar.

Are you using the same tuning for everything on the new songs?

Moore: It's sort of a defined way, the economy of the band. Right now, one guitar each is pretty much what we can afford to be playing. Which kind of doesn't mean anything. When Sonic Youth started, we didn't even think about that. We just kept playing different tunings that required different guitars. At the beginning of Sonic Youth, it was like those guitars were defining the songs that were being written on these guitars, which have certain characteristics. We would lose the guitar, it would break or get ripped off or whatever, then the song would not be the same because that guitar didn't exist anymore. I really like that.

We had enough money and we'd go out and have 16 guitars stuffed in a van in some cases. I feel like I've already done that. At some point, it came to a situation where the guitars became more …. they're better guitars. It was around the time of Sister where we were getting into black Jazzmasters. Even at that time, Jazzmasters didn't have the value they'd have in later days. There weren't many people on the Jazzmaster tip. It was a jazz guitar. The only people I remember at the time …. Tom Verlaine was the model for the Jazzmaster.

Sonic Youth icon Thurston Moore doesn't stray from this '64 Jazzmaster, which he acquired while on tour in 2003. He modded it with a Mastery bridge and trem, Antiquity II pickups, and bypassed the rhythm and tone control.

Photo by Chris Kies

When I was 13 in 1988, not only did I find a copy of Marquee Moon, but I also saw Sonic Youth for the first time. I was obsessed with the Jazzmaster. I got my first one not too long after that for about $300. Things have changed.

Sedwards: You were lucky.

Moore: We didn't think anything of it. We got them because they were good guitars we could afford. We had Mustangs, which were too small. The Jazzmasters I liked for my height, my wing span. Sort of like, “Oh, this feels right." This balance between the Jazzmaster and the Jaguar. I preferred the Jazzmaster. I wasn't quite sure why. Lee [Ranaldo, Sonic Youth's other guitarist] was way more into Jaguar territory. Then when we started seeing bands like Dinosaur using Jazzmasters and using them very well. I remember J [Mascis] being fetishistic with guitars.

What's the tuning you're using?

Moore: The one we're using now is C–G–D–G–C–D.

Rock n Roll Consciousness neatly sums up your career. No matter how far out Sonic Youth traveled musically, there was always the anchor of classic rock songwriting beneath the creative sheets of sound.

Moore: I always liked the balance between the orthodox and the unorthodox. Certainly, me and Sonic Youth had that. Lee was coming out of being a fairly academic guitar player when I met him. He had years playing in cover bands. He was a Jerry Garcia freak. Then when he saw the Talking Heads and Television, he was at the age where he got more into that aspect of punk rock, the more guitar-centered bands.

As opposed to say, the Dead Boys or something like that. He loved it all, like we all did. He was really into what David Byrne was doing, what Verlaine was doing, what Richard Lloyd was doing. That really radicalized him, coming out of his Grateful Dead love and Riders of the Purple Sage. That's where he comes from—there are pictures of him with Deadhead hair, smoking a pipe in front of a hippie Volkswagen.

—Thurston Moore

Yeah, I remember that on the Bad Moon Rising CD.

Moore: Yeah, yeah, yeah. It's in there. So, when we started playing together I was very concept-based. I wanted to do stuff as a songwriter and be in a band. The guitar was just my tool. I thought I could do whatever I wanted with it. I always played guitar to some degree, but not studying it so much. I had an older brother who did. In a way, I let him do that. He took care of that for me. I was more into songwriting and the guitar was just there. I wanted to be a drummer at first.

Really? What happened with your drumming career?

Moore: I attempted to take lessons, but I realized I had no sense of hand-foot coordination. That had to be natural or not at all.

Did your older brother show you any licks when you were starting out?

Moore: Yeah, yeah. I still know them. There were certain things he showed me, like a move that Jimi Hendrix always did. To take this kind of climb. I still can do that. If I play a standard-tuned guitar, that's one thing I'll do. I play it poorly but I know what it is.

Who were you listening to in the pre-punk days?

Moore: Deep Purple, Bachman-Turner Overdrive [laughs]. Montrose [laughs harder].

I recall in Guitar Player magazine in the late '80s, during the Daydream Nation-era, you said Zappa, Sabbath, and Deep Purple were influences.

Moore: Yeah. Zappa, Sabbath, Purple, Floyd.

Thurston Moore's Gear

Guitars1964 Fender Jazzmaster (All of Moore's Jazzmasters have a Mastery bridge and tremolo.)

Fender Thurston Moore signature Jazzmaster

Amps

Peavey Roadmaster head

Marshall 1960B 4x12 cabinet

Effects

Pro Co Turbo RAT

Jim Dunlop Jimi Hendrix Octave Fuzz

Electro-Harmonix Metal Muff

Sovtek Big Muff

Ernie Ball VP Jr.

Boss TU-3W

MXR Phase 90

TC Electronic Hall of Fame Mini

Do you still enjoy a lot of that music?

Moore: Yeah. When I was looking at pre-punk, I was like 15, 16. By the time I was 18 or 19, I started getting into punk. I was 20 in 1978, so you figure when I was 18 or 19, it was beginning. I think by the end of 1976, early '77, I got rid of all my Zappa and Floyd and Sabbath. I literally boxed 'em up and moved to New York. The only records I had were Ramones, Pistols, Patti [Smith]—that was it. Whatever was happening from that ground zero point. Then, seeing those records, at some point in '79 or something, at my mother's house in the basement, they were almost like these big, moldy giants. It was like I had erased them from my mind.

I remember looking at them like, “Oh god." They scared me a little bit. All these old dinosaurs were sleeping in the basement. Those two years, '77-'78, were just so radical and just stepping completely away from that. If a band would play at CBGB that smacked of any of that, they would get hooted off. You'd have people yelling and making fun of them. Like, “Hot fucking tuna. Get out of here, you're stinking up the place." Some flash guitarist would come in and it was like, “Get off the stage. You're bumming us out. I don't want to see it." It was interesting to see that reappraised, eventually. It became a radical thing into its own. To me, that happened with the hardcore bands, like Black Flag getting into Sabbath.

Oh sure, when they went into their instrumental jamming period.

Moore: And Dio. It wasn't so much them talking about jazz, which was okay because jazz was just so odd and something else. But to talk about pre-'70s, long-haired rock was a little audacious. Mascis was big on that, too, with Dinosaur Jr. When Dinosaur first started, J had longer hair. He was wearing beads. He was playing extended leads as if he was Tony Iommi, coming out of punk rock or something. He was startling at first. You know, “No, no, don't do that." But it was so good. It was so weird. That was the beginning of it. Greg Ginn and Black Flag, also. He was just so spastic. I never thought of him as a typical lead guitar player, but he was so special. J was playing as if he was studying Led Zeppelin, which he was.

What are some of the records that were defining guitar moments for you?

Moore: I would say the first five Led Zeppelin records made me more curious. I never really listened to Led Zeppelin records and thought, “I want to play like that." It was just astounding music. The thing that really caught my awareness intellectually with guitar was Neil Young's Decade, the triple album. His choices of his history. I remember buying that record. It was a big purchase in a way. I was with my brother and I said, “I think this is one of the most interesting guitarists." He just said, “Oh really?" He wasn't quite sold on that, because he was all about Hendrix. And so that's the first interest I had in somebody playing guitar, per se.

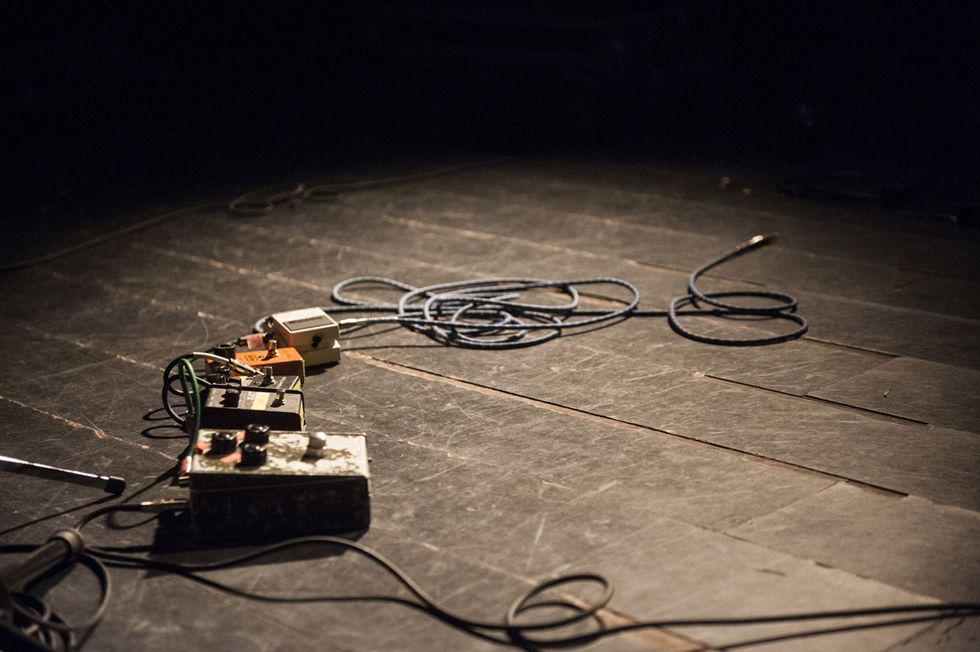

Moore's pedals while touring Spain in 2012 included a Sovtek Big Muff, Pro Co Turbo RAT (his most used pedal), MXR Octave Fuzz, MXR Phase 90, and a Boss tuner. He's used Sovtek Big Muffs since the '90s, but used an Electro-Harmonix Metal Muff on his latest album. Photo by Jordi Vidal

That ties in with how you were saying earlier that you consider yourself a songwriter, not a guitarist. Neil Young really uses the guitar to reinforce the meaning of his songs.

Moore: He's such an interesting guitar player because I don't think he considers himself to be in the same league as somebody like Jimmy Page or Eric Clapton or even Jerry Garcia. Because he's a little bit self-defeating. He says, “I play the same thing every time. I play the same chord. I play the same lead every time. It's all about being in the service of this song." The song transcends it into something else. I got that, in a way. James, what guitar players did you hear and you were like, “I want to do that?"

Sedwards: The first Led Zeppelin album was a big eye-opener. The usual stuff really. I remember hearing the Hendrix Peel Sessions.

Yeah, that's great stuff.

Sedwards: Just hearing this trio creating this massive wall of noise and thinking, “How do you do that?" Listening to Hendrix's rhythm playing. The first two Stooges albums. Never Mind the Bollocks by the Sex Pistols. I could go on and on, really. Sonic Youth, because I felt similarly, like the stuff I loved was very old. When I first started playing the guitar in the late '80s, hearing something like Sonic Youth made me think, “There is hope for this instrument."

James Sedwards has been Thurston Moore's lead guitarist since 2014's The Best Day. Here he's rocking 2015 Riot Fest with a first series '59 Jazzmaster owned by Moore. Photo by Chris Kies

That was exactly how I felt in that era, because I was into '60s music for the most part. Then bands like Sonic Youth and Dinosaur came in. It was raw and not overproduced.

Moore: I first saw Glenn Branca play in '78 or '79. I saw him play in a couple of groups. There was a group called Theoretical Girls and there was a group called the Static. Both were odd and interesting and there was a community downtown of these weirdo bands. I saw him play at a loft space that we played on Bleecker Street. He had his six-guitar ensemble, and it was five 6-string electrics and a bass, a drummer, and himself. He was one of the guitarists.

I would always go up there and hear things. I knew he was on the bill. I was slightly curious because he was lording around town at that point and putting a lot of flyers up and it was all about guitar music. He would be this statement: “Guitar music at Tier 3." Rhys Chatham's guitar trio as well. It was all about guitars. That was curious to me, that they were doing that. I wasn't quite sure how to take it.

I remember being there, and then he began to perform and it really blew my mind. It hadn't been blown in a while. Because it was accomplishing something I had in my own mind. I wanted to do something with guitars where it had this sound: like taking the guitar sounds I really liked off Steve Jones' playing and Never Mind the Bollocks, but do something else with them so they were this raging thing that was almost an artful heavy-metal thing, without the corniness of heavy metal.

I had no idea they were playing alternative-tuned guitars. I never even thought about changing the traditional tuning to anything else and working with it. So I was thinking it would be great to play something that sounded like that, and there it was. I was levitated and I would go see them a few times more and eventually realized it by talking with either him or some of the other guitar players or just whoever. Lee Ranaldo, who I'd just met, was playing in different bands.

Was Lee Ranaldo playing with Glenn at that point?

Moore: Not at that point. In that, Glenn was tuning those six guitars into one guitar. It was like six strings. To me, that was really interesting. I'm not quite sure if it was the standard tuning where he was the E and the next guy was the A. Each guitar was one note with, like, a multiple simple gauge. So one guitar would have all high E strings on it, all non-gauged strings. I think you would call that the soprano guitar. I didn't really realize it at first. You can imagine what that would sound like—all .009 gauge strings tuned to a high E, like aaaahhh. That was just so fantastic sounding to me, coming out of little amps in a small room, and it was loud so the amps were full on. Although the volume was an element, and he was working with volume to create these other sounds that would use ... what do you call it? Resultant overtones?

That was one of the first times I really thought of wanting to focus on the guitar more than just writing songs and recording them. I answered an ad in the paper to play with [Branca]. That's when Lee was playing with him. I saw Lee at the rehearsal, but I didn't get the job at first. I went to his apartment and he said, “I do a lot of things where I double strum. Do you know what that is?" I said, “What do you mean, double strum?" He's like, “You know, when you double strum." I was like, “Well, that's all I do." He's like, “Not everybody can do that." I was like, “Why not?" So, he showed me some things, and I was just like, “Uh." Then he just looked at me like I don't know what.

James Sedwards' Gear

Guitars1959 Fender Jazzmaster

Amps

Peavey Roadmaster head

Marshall 1960B 4x12 cabinet

Hiwatt DR103 head

Hiwatt SE4123 4x12 cabinet

Fender Hot Rod DeVille

Effects

Boss TU-2

Jam Pedals Wahcko Plus

Pete Cornish P-1 fuzz

Pete Cornish G-2 distortion

Pete Cornish SS-3 preamp

Jim Dunlop Jimi Hendrix Octave Fuzz

Dinosaural Tube Bender

Pro Co Turbo RAT

MXR Phase 90

JAM Pedals WaterFall

Boss DD-2 Digital Delay

MG Music That's Echo Folks

Analog Man ARDX20 Dual Analog Delay

DigiTech PDS 1002 Digital Delay

He later told Kim [Gordon, bassist/vocalist in Sonic Youth], because Kim knew him. She was writing a story about him and some other downtown musicians for an art magazine at that time. When I met her, we were talking about him and I said, “Well, he never called me back." She goes, “Oh yeah, he told me about you. He said he thought you were really wild and he didn't want to be the person to contain you." I was like, “Contain me, contain me! I want to play with this guy."

Then I got the call. I don't know; maybe it was political. Maybe Kim put in a good word for me or whatever. I don't know what it was, but then I got the call and I got contained. We had a bit of a thorny relationship because sometimes he was very demanding about what you were supposed to do. It was very specific and explicit. Which I was okay with. I think there were some moments where I challenged him.

Would you say your time with Glenn, plus your discovery of compositional direction, has been one of the biggest milestones?

Moore: It was definitely significant. It also put me into a community of other players who were interesting and intriguing musicians who'd come from different places. Ned Sublette was playing with them at the time and he was coming out of this long history of being involved with music scenes with La Monte Young. At the same time, he played with Rhys Chatham, who was the angel to Branca's devil, as far as that was concerned.

They'd been in a band together, which I saw. So I started playing with Rhys as well. It was a bit of a pool of downtown musicians, guitar players. Rhys would pull from Glenn's pool and vice versa so we were being traded back and forth. Lee played with Rhys once. It was a really interesting time and I got to meet all these different people. You would glean all this different music history. I was definitely the youngest guy. I immediately started my own band and got Lee involved pretty fast.

Your current lineup seems like a band with great chemistry. While recording the new record, did it have an organic band feel, like everybody's giving their input and pushing everything to a high level?

Moore: It did. We've all been in bands for years.

James, what are some of the bands you've been in?

Sedwards: Well, I have my own band, which is called Nought. I've done a couple of bands that have made it over here. One was called Country Teasers. I toured here with a band called Wacko. Bands you may not have heard of.

Guitarist James Sedwards and bassist Debbie Googe (My Bloody Valentine) play with Thurston Moore during the

2014 BIME Festival in Bilbao, Spain. Photo by Jordi Vidal

Thurston, you've been playing with Steve for so long. Does being locked in with such a solid drummer free you up to go places?

Moore: There's certainly that trust we have in each other, that we know each other. First and foremost, he's a very good drummer. There's nothing rote about his playing. He's very creative. He's not an intentional experimental drummer—let's put it that way. He's really into classic rock 'n' roll playing. He's very interested in the challenge of playing in a band that has a real intensified avant-garde discipline. He's a Beatles freak. He's a Motown freak. He's so immersed in music lore and history and listening and reading and playing. The fact that his favorite drummers are swing drummers and soul drummers is great. He's ethical and responsible, and he doesn't drink or smoke or do drugs. I was like, “If you want to swing, you've got to get drunk. You got to get high. You got to get in the dirt a little bit." He proved me wrong on that. “I can swing the fuck out of these drums and keep the time and throw whatever you want to throw at me."

I always took it for granted. Before Steve, we had Bob Bert playing drums. There were a few other drummers who came in and out, some better than others. Then when Steve came in, immediately this concision came in. It was like, “Whoa." People said, “Your band has jumped up a few notches because of that kid. He's holding you together." Because between Lee, me, and Kim, a lot of dynamics were pushed and pulled with the different levels of our playing. Steve became this great element in the band, as far as being the timekeeper and with rhythm ideas.

The anchor, as Mike Watt would say.

Moore: The anchor. I took it for granted and then after I started playing with other drummers, I realized I really missed Steve. Where I didn't have to turn around and go, “Where the fuck are you?" When James and I were playing together as a duo in London, one of the earliest things we did was supporting Lee's touring group at that point, which was Steve Shelly and Alan Licht. Steve heard the Best Day material. It was just instrumental at that time, I think, and he immediately said, “If you want somebody to play drums with this stuff, let me know." I was like, “Yeah, you're certainly the first person I would want to play drums."

How did Deb get into the picture?

Moore: It was James' idea. It was a good idea.

She works out so well—especially moments when that fuzz bass comes on. It's like My Bloody Valentine right there.

Sedwards: I knew her before the group. When we were getting a drummer, it seemed we needed a bass player. She'd just come off a year of touring with My Bloody Valentine, and not doing much as far as I was aware. She just seemed to be the perfect person.

What guitars were you both using on the record?

Sedwards: We're both using Jazzmasters, the ones we tour with.

Thurston, yours is a '64 or something like that?

Moore: My Jazzmaster is …. What year do you think mine is?

Sedwards: I think '63 or….

Moore: I think it's '63. [Editor's note: There are many Fender inconsistencies from this time period, but this guitar's label indicates it was made in 1964.] The gold one James is playing is a guitar I've had for a long time. That's a first series Jazzmaster.

Sedwards: That's a '59.

So almost a birth year guitar for you.

Moore: Yeah, being born in '58, I was born the year Jazzmaster was born. Sometimes I get the guitars mixed up. I was talking to the Sonic Youth guitar techs who really look at the guitars. I think the history is, the gold Jazzmaster is a guitar that was given to me via Patti Smith after Sonic Youth got its equipment notoriously ripped off in California [in 1999].

YouTube It

Thurston Moore and James Sedwards chime and choogle on '59 and '64 Jazzmasters, lighting up this cut from Rock n Roll Consciousness.

The Patti Smith Group had their equipment ripped off at some point in the '70s, so she was very understanding of the grief we were going through. She was doing a show in Northampton, Massachusetts, with her group and staying at our house.

She said, “I know what it's like. I want you to have one of our guitars." I said, “You don't have to do that." She told her guitar tech, “Go get that guitar." It was that gold Jazzmaster, and I was like, “This is really sweet." I held onto it for a long time. I remember telling Tom Verlaine that she gifted me this guitar. He's like, “I can't believe she gave you that gold Jazzmaster."

Envious?

Moore: He always eyeballed it, I guess. I was very appreciative. I think she's just like that. I talked to Kevin Shields and he's like, “Oh, she gave me a guitar, too." When she works with people, that's one of the cool things Patti Smith does. At some point, we had the neck taken off to look at the guitar. The luthier who was doing it froze because it was penciled 1959. He was like, “No, no, no, this can't be happening. They only penciled the first series." He was like, “I can't believe I'm looking at this. I've looked at 6,000 Jazzmaster necks and I've never seen this before in my life." It does look beautiful.

The three guitars I always remember were the blue and the red Jazzmasters and the Mustang modified with three pickups.

Moore: The blue Jazzmaster was my most central guitar. That, and my pedal setup was just really refined. That was kind of a bummer. Like my Peavey head [getting stolen].

Do you have any of those Peaveys anymore?

Moore: Yeah, yeah. James found one a couple of years ago that we keep here in the States. They're wonderful.

Sedwards: That's what we used on the record.

So, the mighty Peaveys live on!

Sedwards: Yeah, yeah. There's two over in London that we use in Europe. We've got three.

Moore: The Peavey Roadmaster.

Any effects that either of you especially like that you've been using recently?

Moore: James is much more effects-centric than I am. I use three different variables of fuzz, a Turbo RAT. The bigger overdrive pedal that I use sparingly, is it a Metal Muff?

Sedwards: Yeah, Metal Muff.

You've used the RAT for a long time, right?

Moore: I always used RATs and then I graduated to Turbo RATs, which are rugged and dependable. They sound big—they have a good sound. I have a few different outlying pedals like a phase shifter and a chorus pedal, but I rarely go near them. When I play improvised music—like completely free and improvised devoted music—I'll use more of an array of pedals, usually.

Any noise-improv works on the horizon?

Moore: I live in a London community where that's a prevalent activity, so I play gigs like that every other week or so in small little clubs with different players. English players like John Russell or John Edwards, with some drummers I play with, and Al [Licht] is a friend of James and mine.

Then there's people who come through town. Different noise players will Facebook message me and say, “Hey man, you want to do a duo?" I'm like, “Of course I do." My booking agents say, “No, you can't be playing there. You can't do that." The promoters say, “You were just here playing for zero Euros. Why should we give you anything to come back here?" I'm like, “Sorry." The idea is I would have a different name when I go do these gigs so it doesn't screw up the rock-band thing.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)