Of all the lucky things one gets to do in life, surely camp is one of the best. What’s not to like? You get to decamp (ahem) from your real life and flee to some beautiful hideaway. Strangers become fast friends, and there’s an invigorating intensity to the shared purpose, whether it’s weaving lanyards, learning archery, or, in my case, playing bass.

The Warwick Bass Camp is unlike any event in the world. First, the setting. Warwick is headquartered in Markneukirchen, Germany, a bucolic little village near the Czech border, surrounded by lush forest and rolling, cow-dappled hills. Its beguiling Central European charms aside, Markneukirchen has a rich heritage in instrument making, dating back centuries. And while this tradition still continues in all its mom-and-pop glory, with small lutheries and brass instrument makers scattered about, Warwick (and its sister brand, Framus) has brought a decidedly modern edge to the local trade. Its carbon-neutral factory (a music industry first) is a gleaming Teutonic masterpiece, all brushed stainless and exotic hardwoods. Picture a Porsche dealership, but instead of 911s, the showroom is packed with boutique basses.

The wünderbar architecture is a good clue to the financial resources at play here, as the camp made clear. Whether it’s the resort-like (if slightly surreal) hotel—a former Communist party retreat, according to the scuttlebutt—or the daily catered meals, or the ever-present, ever-cheerful staff, Warwick has undoubtedly invested heavily in making its camp a nearly luxurious affair. Said President Hans-Peter Wilfer, “When we invest in the community like this, it’s good for the whole industry. This isn’t about getting people to play Warwick. It’s about creating an amazing experience for the campers that they can then share in their own communities. It’s good for all bass players.”

This investment is perhaps most obvious in the sheer density of iconic talent assembled to teach the campers. When John Patitucci, Victor and Regi Wooten, Leland Sklar, Steve Bailey, and Stuart Hamm (among many other bright lights) can hang for the week, you know the organizers are deeply invested in the event.

The camp began with the first of what would be five dinners at the Alpenhof, a German restaurant and hotel straight off the Universal backlot: waitresses in bust-squeezing peasant dresses, men proudly rocking lederhosen, and enough beer and sausage to sate half of Milwaukee. The coolest thing about the place, as we’d soon discover, was the dining room stage, which would play host to ridiculously cool jams between students, between teachers, and between students and teachers the whole week long. After introductory remarks by Wilfer and a few of the teachers, and some post-chat jamming, it was off to bed for much-needed sleep.

And So It Begins

I yawn myself awake, self-satisfied that I’ve managed to get a decent night’s sleep, jet lag be damned. Tummy rumbling for breakfast, I arise to shower and head out, errantly glancing at my watch as I peel back the covers. Oops. It’s 1 a.m. Blech. Not to belabor the point, but this was a first glance into what the European attendees have over us Americans: sleep. If you’re thinking of attending next year, do yourself a favor and come early. Acclimate. Have a stroll into town. Feel human. It makes all the difference.

Once camp began, it was basically all-day clinics, augmented with much informal hanging. I couldn’t possibly cover the full breadth of the material on offer from the amazing array of clinicians, so I’ll touch on the stuff that touched me most.

John Patitucci

Interestingly, bass virtuoso John Patitucci focused his clinic session on rhythm. “The truth is, nothing else matters comparatively,” he told students at Warwick’s annual bass event.

Of the many big-time pros who double on acoustic and electric, John Patitucci is the gold standard. His resume is as broad and extensive as his knowledge is deep. From Chick Corea to the L.A. session scene to Wayne Shorter, few bass players exude the skill, versatility, and positive spirit of a true professional like Patitucci.

Interestingly, for someone as well-versed in harmony and its application in jazz and classical music, Patitucci’s clinic primarily focused on rhythm. “Rhythm is essential,” he said. “Most players simply don’t pay as much attention to developing their rhythmic skills as they do theory. But the truth is, nothing else matters comparatively.” Patitucci marked Wayne Shorter cohort Danilo Pérez as a major influence on his own rhythmic development. The Grammy-winning Panamanian pianist is a master of the syncopated, complex rhythms of Latin America. Said Patitucci, “Before I started to hang with Danilo, I could play Afro-Cuban pretty good, but in my heart, I knew it wasn’t totally happening. He turned me on to really digging into clave and understanding how it works in an ensemble.”

“A player needs to have a great feel,” he continued. “To lay down a big wide beat that’s easy to build on, you have to know when to play straight, when to play a swing or triplet feel, and when to play a combination of the two. Ask yourself, can you play in a wide variety of tempos and make them all feel great?”

Patitucci went on to describe the woodshed habits that make a player get better. “Transcribe great bass lines from recordings. Use your ears and memorize the lines. Listen to Bach. We also need to develop our ears to respond to harmony quickly, intuitively, and emotionally. Rhythm and harmony influence each other in subtle ways. You can always hear the difference in drummers who respond to the harmonic shifts in the music, as opposed to the ones who play a particular beat no matter what happens around them.”

Moving into the harmonic realm, Patitucci stressed the importance of total fretboard awareness. Fig. 1 shows a brief melodic minor exercise he shared with the class. One powerful tip he offered was using triads as a way to avoid the scalar rut. In the case of G melodic minor, for example, instead of playing a scale-based line, consider the tonality as the combination of three triads: G minor, C major, and D major. It’s an excellent way to create more interesting and dynamic lines.

Victor Wooten

Needless to say, living legend Victor Wooten is an adept clinician. Beyond his illustrious playing career, Victor is the brains behind the long-running Bass Nature Camp. His warmth and insight were inspiring; his attitude is always one of the student. “I learn as much from you as you do from me,” he told us. “So take notes, and I’ll do the same.”

Accompanied by his scary talented 12-year-old son Adam on cajon, Victor began the clinic with a funky, mid-tempo I-IV groove. Once he set it up, he pointed to students in the room to contribute something to the budding groove. Some immediately locked in; others struggled to find the key; still others played too much or too little. Inciting individuals to play along, Victor would modulate the key without warning, forcing students to use their ears to adapt to the new tonal center. Most students couldn’t quite keep up.

The point of this exercise, Victor pointed out, was to underscore the importance of listening. “When you’re in a conversation, what do you do? You listen. Playing is the same as talking. We’re in the rhythm section! Approach it that way. If you play a good groove, there are no wrong notes. There’s only 12 notes, and if you’re comfortable with all of them, why do you need the key? If you can really feel the impact of all 12 notes, and deliver the notes with a good groove, there’s zero percent odds of you playing something wrong. Find the key in yourself! Notes don’t matter if it doesn’t groove.”

After this illuminating exercise, Victor wrote his list of the 10 equal parts that make up music:

1. Notes (this includes all of music theory) 2. Rhythm 3. Dynamics 4. Articulation 5. Tone 6. Phrasing 7. Technique 8. Feel 9. Space 10. Listening“Two through 10 add up to groove,” Wooten said in summation. “If they’re right, one can’t be wrong.”

Steve Bailey

Fretless 6-string bass wizard Steve Bailey is a singular talent. His deeply developed vocabulary on his extraordinarily tricky instrument is unique. As comfortable laying down a fat groove in a funky jam as he is using artificial harmonics and subtle articulation to create lyrical, gorgeous melodies, Bailey is a true innovator.

Given his reputation for solo and dual bass (often with longtime collaborator Wooten), Bailey shared a story about the professional risk of developing a reputation for solo playing. “Early in my career in L.A., I got a call that Steve Vai was looking for a new bass player and wanted me to come down and jam. Excited, I packed up my stuff and headed out to his studio. Steve introduced himself and asked me to play some solo bass. So I went for it, man. I was in the zone. I closed my eyes and did all my good stuff. Really feeling it. I was so excited when I opened my eyes. Only problem was Steve wasn’t there. Worried, I asked someone else in the studio where he went. Apparently he got on his motorcycle and took off about 30 seconds after I closed my eyes and got in ‘the zone.’ The lesson is: Don’t miss the gig. Be careful about how you play, and what you play. Steve Vai wasn’t a solo bass gig.”

To Bailey, good bass playing can be boiled down to the four T’s: Time, Tone, Taste, and Technique. “Get that stuff together, and you’re good to go.”

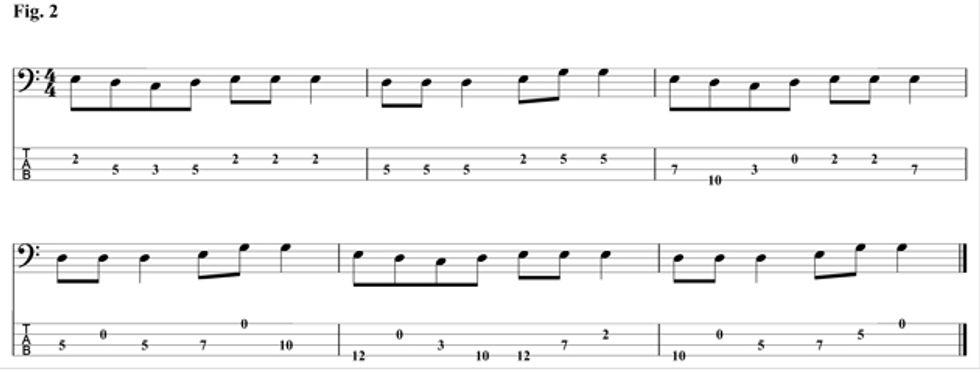

Given the sheer size of his fretless 6-string’s wide, unlined fretboard, a lot of students were curious how he developed his intonation. First, he likes to practice with his eyes closed: “Use your ears as the guide.” Then, he offered a great practice routine for developing fretboard awareness and accuracy. Example 2 shows the first two bars of “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” first in the most conventional position. The exercise requires playing that same melody, but varying the position of each note across the entire fretboard. Check out the tab for a few examples of how this works, and be sure to apply the concept to other melodies for maximum benefit.

Alphonso Johnson

The opportunity to hear, hang with, and generally observe the masterful Alphonso Johnson was a personal highlight of the trip. Simply put, Alphonso contributed inimitably funky and tasteful bass to several ensembles and artists who redefined 20th-century music, including Weather Report, Wayne Shorter, and Billy Cobham. Beyond his bulletproof resume, Alphonso is one of the warmest people you’ll ever meet, always ready with a smile and a heartfelt word of support.

He emphasized that bass playing should start with the root, like a tree. A thought-provoking handout provided some relevant wisdom: “Everyone wants to be daring, creative, and original. Everyone wants to do things in new ways. But unless we return over and over again to the basics, we will have no chance to truly soar. Do not forget the root. Without it, we can never issue forth true power.”

Thoroughly convinced, the class then got Alphonso’s list of tools to embellish our performance:

1. Strong downbeat 2. Syncopation 3. Legato and staccato 4. Call and response 5. Attitude

To demonstrate the potential that each facet on the list can offer, Alphonso flipped on a drum machine and improvised the line in Example 3. He divided the room in half and had one side play Bar 1 and the other Bar 2. Slowing down to teach the students who couldn’t quite nail it, Alphonso patiently explained how the line demonstrated each part of the list. It was especially fun when he asked the students to apply some attitude. I got a good glimpse of some international “bass face.”

Stuart Hamm

Bassist Stuart Hamm concentrated on teaching his fellow bassists the importance of physical health and breathing.

Solo bass pioneer Stuart Hamm may be renowned for his sophisticated tap technique and the remarkable self-accompanied tunes his chord-plus-melody concept enables, but his clinic was really focused on maintaining our physical selves for long, rewarding, and pain-free musical careers. While he did start with a stirring mash-up of the Beatles’ Abbey Road B-side and Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata,” he quickly pivoted to tips and techniques to prevent nerve and muscular pain.

Most important to Stuart is proper breathing technique. Burdened with laying down a good groove, making the changes, and enhancing a tune, bass players often forget to breathe as their brains tackle formidable musical challenges. One simple but effective exercise he described was playing a simple major scale, inhaling on the way up and exhaling on the way down. Not only does this reinforce the subconscious relationship between the breath and notes, but it also has an undeniably calming, meditative quality.

Jonas Hellborg

John Patitucci and Jonas Hellborg performing at one of the nightly concerts.

Swedish bass virtuoso Jonas Hellborg is one of the instrument’s great thinkers. His inspired career has seen him anchoring the Mahavishnu Orchestra, partnering with the late, great guitar wiz Shawn Lane, and collaborating with Indian classical musicians in a variety of compelling settings. Beyond playing and performance, Hellborg is a self-taught amplifier designer and audio engineer. Hellborg largely designs Warwick’s line of amps and cabinets in his lab at Warwick HQ.

Hellborg’s clinic followed a different track than most of the other teachers. He was adamant that the setting was a seminar and discussion, not a performance. Thus he didn’t play. Instead, he initiated a fascinating back-and-forth about the fundamental nature of music. It’s hard to summarize, but the following are some of his most salient points:

“What is bass? A guitar? A double bass? A role? Who do you want to be? What do you want to sound like?”

“Why do you play music? For me, it’s a necessity. If I don’t, I get physically sick.”

“Music is about interacting with human beings. We need input for an ordered output. The brain is a Petri dish.”

“Music is an aural endeavor. It all begins with sound. It’s not physical. Our ears are our tools. Think about how you create a sound. You can just play a G. But where on the string? What part of the finger? How do you angle it?”

“There is a gravitational relationship between all pitches. Math, sound, and logic. Music is about life. It’s what we experience. Music about music is pointless. You can’t do it without craft. You have to acquire the art of it. You don’t have to work on individuality; we are all mirrors. All the light in the universe is already there.”

I wish space allowed a comprehensive report on each and every clinic. Leland Sklar regaled his class with tales from deep in the session trenches, even breaking out a Warwick semi-hollow body for a jam on the Bill Cobham fusion classic, “Stratus.” Meshuggah bassist Dick Lövgren explained some of the polyrhythmic concepts that lie beneath his band’s über-complex metal. And on and on. Frankly, the camp had such extreme bass talent, it’s going to take months to process and unravel the insights provided.

And So It Ends …

All good things must come to an end, and in the case of Warwick’s Bass Camp, it ended in fire and thundering bass lines.

Camp concluded with a beautiful dinner in Warwick’s pristine auditorium, featuring performances by many of the week’s teachers. After dessert, we all retreated to the balcony to see a stunning fireworks show (with a funky bass soundtrack, of course). As 100 bassists gazed up at the sky in unison, it became clear: This was a special event, and the bass world is better for it. It’s a good thing, then, that Warwick is already committed to next year. Until then, check out Warwick’s YouTube page for tons of video from the event (youtube.com/user/warwickofficial), and start pinching those pennies. Next year promises to be even bigger and better. Be there, or be square.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)