The fire and magic that happens when a charismatic frontperson and a gifted musical foil find symbiosis is truly beguiling. Elvis had Scotty Moore, Bowie had Mick Ronson, and for a few charmed, arguably career-defining years, Prince had Wendy Melvoin.

Melvoin has come a long way since her days sparring with the late icon. She started playing guitar with Prince’s band in 1983, and was a permanent fixture and cowriter on the Revolution’s three seminal albums: Purple Rain (1984), Around the World in a Day (1985), and Parade (1986). After Prince disbanded the Revolution in 1986, Melvoin went on to enjoy success fronting her own pop group, Wendy & Lisa, with keyboardist, Revolution alum, and lifelong musical partner, Lisa Coleman. The Los Angeles-born Melvoin has since morphed into a perpetually in-demand session player, songwriter, producer, and composer, with a resume that reaches far and wide into disparate spheres of the music and film worlds, and includes the likes of John Legend, Seal, Grace Jones, Glen Campbell, Sheryl Crow, and Joni Mitchell.

While Melvoin—the daughter of the legendary Wrecking Crew pianist Mike Melvoin—undoubtedly possessed impressive skills as a rhythm guitarist and hooksmith when she initially caught Prince’s attention at the green age of 19, she makes no bones about the impact her time with the innovative Master from Minneapolis had upon her development as a musician and composer. In fact, she refers to that period of her career as her “Juilliard or Harvard years.” And for anyone who’s taken the time to gaze beyond the mystical purple glare and truly analyze Prince’s Revolution-era output, Melvoin’s contributions as a texture player and rhythm ace should be immediately apparent, particularly on the magnum opus that is Purple Rain, which put forth a cadre of unforgettable singles that all featured heavy doses of Melvoin’s guitar and vocals.

While the band unfortunately never made good on the perennial reunion tour rumors that circled about through the years, Prince’s tragic passing prompted the group to reunite and put together a tour as a means to both grieve the loss of their friend and leader, and to celebrate the tremendous music they forged in his keep.

Melvoin took the time to catch up with Premier Guitar between Revolution tour dates and reflected on her time working and learning with Prince, the craft of pop guitar work, and the healing process that’s come with this tour.

Was it challenging to relearn these tunes after all the time that’s passed, and was there a lot of adjustment required to play parts that weren’t originally yours?

You know, it was really an interesting process just trying to just figure out the best way to be respectful of the material and do justice to those parts that weren’t originally mine, but without being a showboat, which is something I just absolutely have no interest in being. Prince’s soloing was super impassioned, and, of course, he did a lot of calisthenics, but when he would reach for those wild high notes, that was really like an extension of his voice or singing. So that’s kind of where I wanted to be, honoring that side of his playing. I didn’t want to be “the fast machine”—I’m not interested in the athletics, honestly.

When it comes to playing the parts I had been playing, I’m an infinitely better player than I was when I was 19. I’ve been playing for 40 years now, so I’m just a better player and that meant the task at hand itself wasn’t hard, but the emotional aspect and approach to playing those songs was something I really wanted to be mindful of.

“I didn’t want to sound like Roger McGuinn, so we modified them,” says Revolution guitarist Wendy Melvoin of her famed purple Rickenbackers of the Purple Rain era. Her Rics were loaded with G&L pickups and the guitars’ f-holes were sealed up, so there was no air moving in them. Unfortunately, Melvoin’s Rics were stolen about 25 years ago. Photo from Wendy Melvoin

As far as calisthenics go, I always felt Prince was one of those rare athletic players who was extremely dexterous, but always made every note count for something. Even when he was playing something tricky, it wasn’t banal.

Yes, it’s true! Sometimes he had moments where I’d look over and he’d be going for it and I’d laugh to myself and say, “You don’t even know what you’re doing right now!” But by the time he passed, he was undoubtedly a true master at the neck of the guitar. He just knew the thing so damn well.

What’s the most important thing you learned from working with Prince as a guitarist and a composer?

Space. Learning the definition, in Prince’s world, of what “space” really meant between five people on a stage, and the discipline it takes to not stray from script in terms of what you’re playing. Don’t start having a musical dialogue with solos, or throwing new notes in where they aren’t expected, when you’re supposed to be doing justice to a song as it was intended.

Our accepted ... even honored job, was to give him the space to be the musician he wanted to be onstage. When it came time to do things in the studio, it was a different experience, and there was a lot of give and take with that because he relied on creative ideas coming from me. But as a side guy onstage, I was there to help him be the best he could be.

I always considered Prince to be the greatest black hat chef on the planet, but he has to have the best team in that room to support him, or that meal’s going to turn out like shit. I really believe that and he just built a great team, particularly with the Revolution. I think we all walked away with an incredible amount of discipline; those were my Harvard or Juilliard years, so to speak. It definitely translated into my work ethic. I have an extremely high work ethic to this day and I work every day on my composition skills and getting better at my instrument, and that came directly from those years of strict discipline—of listening, learning, and understanding what the dialogue was between the musicians onstage and how to best function within Prince’s world.

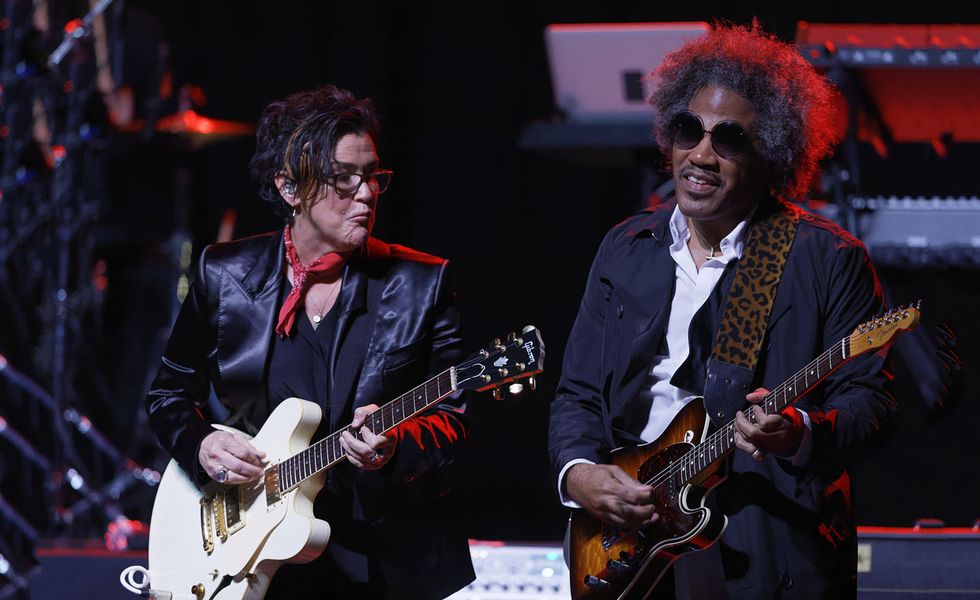

Wendy Melvoin shares licks with Rob Bacon during the Revolution’s stop in May 2017 at the Majestic in Detroit. Gibson gave Melvoin her white ES-335 in 1985, and she’s been playing it since. “That guitar was used for the entire Parade Tour and our last tour as a band,” she says. “Actually, Prince called me about 6 months before he passed and goes,

‘God! Do you still have that white 335?’ And indeed I do.”

Photo by Ken Settle

Could you describe the chemistry you had with Prince as his guitar foil?

Well, the thing he liked about me was that I never considered myself a female guitar player—I was simply a guitar player. He really respected that about me, but at the same time, if you look at things like “Computer Blue,” where I was getting on my knees and we did something similar in the onstage theatrics to Ronson and Bowie’s interaction, there was an obvious gender definition happening, but what turned it on its head is that we were very fluid in our gender roles onstage. But I never really considered myself the “chick” guitar player. I know everyone else did, but I didn’t, and so I didn’t define myself that way at all. I relied upon my playing to define myself, and that was something he picked up on.

As a player, I was able to communicate with Prince very well. I knew exactly how he worked as a guitarist—particularly that right hand of his. I knew what he wanted to hear, and I took tremendous pride in being able to sound like a part of him while still sounding like myself. The real magic, to my ears, happened when the mixture of my playing, Prince’s lead guitar, and Lisa Coleman’s keyboards jelled. It was like another language or Shakti, as far as I’m concerned. We wouldn’t have to do much verbal communication at all because the initial seed that came out of us worked so well in that environment. We had a great musical connection. It wasn’t natural, because each one of us had our own singular talents that we brought to the table, and we had to work on it, but it was unreal when it happened. Prince himself could play just about anything, though. However, he never could play like Lisa; that’s the one musician throughout his entire career that he could never play like. She has her own singular thing that even he couldn’t cop, which is a serious distinction.

I, on the other hand, was sort of the great facilitator. I could morph between styles and sounds easily. That’s why I ended up being a sought-after studio musician for such a wide variety of records and musicians. I’ve done everything from Los Lobos to Joni Mitchell to Madonna, etc. But I think my strength is morphing, and that kind of thing worked really well with Prince and I and our musical dialogue. We had the same influences, too, although he was a big Carlos Santana fan and I was not! I was a John McLaughlin fan, though they did do a great record together.

As an insider who undoubtedly saw more of Prince as a guitarist than many, was there anything you found extraordinary about his playing that might not be immediately obvious to an outsider?

If you want to see the real magic in Prince’s playing, it’s not his left hand; his picking hand was everything. You’ve got the blues dudes that use their thumb and finger, or the Albert King dudes that use their fingers to really pluck the hell out of the strings and muscle it, but Prince, when he played rhythm, could go from picking to seamlessly hiding that pick between two fingers and doing this form of almost bass slapping that would bring out these funk parts in a way that sounded like double-speed guitar, and it would always blow my mind. He was really great at that, and rhythm work in general.

He was also just so great at writing a guitar hook. He knew how to craft a guitar hook that would do exactly what was needed.

You’ve always displayed a real gift for weaving together incredibly funky guitar rhythms. Do you have a philosophy to penning those parts?

I don’t really have a philosophy, but it’s just what naturally comes out of me. I can tone it down if need be, but a lot of the time, it’ll be what’s asked of me when I go into a session. I played on a John Legend record last year that Blake Mills was producing—who, by the way, I think is the best up-and-coming guitarist I’ve ever heard—but we sat in a room together and had a musical dialogue, where we played back and forth off of each other on this one track. Because Blake would go more avant-garde with his rhythm playing, I tried to go for the more old-school, straight-ahead Telecaster through the board thing, with a compressed kind of sound, because it made for a great contrast to what Blake was doing. So if there’s an overarching philosophy Ido have, it’s in providing contrast and jelling.

On the other hand, I did a Neil Finn record a few years ago where I played every style imaginable on guitar and bass and it just happened to work really well for his songwriting. The playing I did was focused on putting weird little twists on his songwriting, which happens to be some of the best I’ve ever heard. But my goal on that record was to help his music sway a little more, instead of just being so straightforward. It’s about serving the song and the task at hand.

Wendy Melvoin’s Gear

Guitars1985 Gibson ES-335 (white)

1967 Gibson ES-335

Amp and Effects

Kemper Profiler

Strings and Picks

Various .012- and .013-gauge flatwound sets

The main guitar riff on “Computer Blue” is one of my favorites from the whole Prince discography. Could you detail your involvement in the writing of that tune, and also tell us how that doubled-lead lick in the middle that you two play came into being?

Well, the main hook at the beginning, that’s mine. Lisa and I were at rehearsal at a warehouse space and demoing music that would all wind up being Purple Rain stuff, and Prince walked in on that day and it was something that piqued his interest, so “Computer Blue” was based on that hook. We all worked on it together from there.

The triplet guitar solo part is, interestingly enough, my albatross! Every musician has their muscle memory and that lick is just Prince’s on perfect display. It was a part that he played so naturally. My muscle memory just doesn’t have the same freedom as his did, and that was just a part that came to him so easily. So, since I started playing that lick at age 19, to this day when I play it on my own, I’m not doing the part justice. However, I’ve learned to give myself a break on it because it’s just one of those things that my muscle memory won’t allow for. It’s been a real trip trying to study that particular pattern and why it was so effortless for him to play, but for me, I have to be incredibly mindful because my hands just don’t work that form the same way.

Do you recall the signal chain you used to get that giant sound on the main guitar hook on that song?

Sure do! For my guitar, it was a Boss compressor, probably a CS-1, directly into a TC Electronic distortion pedal, into an MXR boost, into a Cry Baby Wah, then my chorus, the brand of which escapes me right now, and then into a volume pedal, all of which fed into a Mesa/Boogie Mark II head on a cab with, I think, a pair of JBL speakers. I was using one of my modified purple Rickenbackers when we recorded it.

Wendy Melvoin formed Wendy & Lisa with Lisa Coleman after the Revolution disbanded in 1986. The duo have been making music together since the early ’80s. Photo by Joshua Pickering

Those purple Rickenbackers are pretty iconic in their own right. What were the modifications?

They looked like a Ric, but they really weren’t after we got done with them. They were loaded with G&L pickups, and had the f-holes sealed up, so there was no air moving in them like a stock guitar. Some motherfucker stole them out of my rehearsal studio about 25 years ago. I’m on eBay every day and I’m looking in pawnshops all over the world for those guitars. It’s a massive bummer that they’re gone.

So one of Prince’s things is he wanted me to play big-bodied guitars. For whatever reason, he liked the idea of me holding a big guitar. He had me playing this huge Gibson SJ-200 acoustic and I just hated the thing. I’d be like, “The fucking thing is too big, man!” and he’d be like, “It’s great! You gotta play it! It looks great!” I hated it. I wanted my little Teles and my little Mustangs—that’s what I wanted and that’s what I play now! The only big-bodied guitars I still have and adore are my old 335s; that’s really what I stick to. But back then, he wanted me to play these big guitars.

So we got these Rics, but I didn’t want to sound like Roger McGuinn, so we modified them. This guy at Knut-Koupée Music in Minneapolis did work on Prince’s beautiful Hohner Telecaster and my own guitars. We talked about getting them painted for the Purple Rain tour and film, and installing those G&L pickups so they’d have more sustain, and just things that made sense for the stage setup we were using. We were playing with these massive side fills, like stadium shit, and I’ve actually lost hearing in one of my ears because of those side fills! The point is, I couldn’t have any feedback because of the proximity to those side fills, so we clogged up the guitars, and that’s what they became.

I’ve seen that white Gibson ES-335 in your hands more than any guitar over the course of your career. What’s the story on that one and what do you love about it so much?

Gibson came to rehearsal back in 1985 and presented me with that guitar before we left for the Parade tour. It’s been my jewel. I have a few other 335s from 1967 that are absolutely phenomenal, too, but the white one was made for me and I now play it consistently. I only play it with flatwounds and it’s just been a dream guitar. That guitar was used for the entire Parade tour and our last tour as a band. Actually, Prince called me about 6 months before he passed and goes, “God! Do you still have that white 335?” And indeed I do.

Were you using flatwound strings back in the day as well?

No, I just started using them in the past 10 years. I keep slinky rounds on certain guitars I use in the studio, but for the most part, I really like flats. They have a sound that’s just really great for me.

Looking back, do you have a proudest moment or contribution as a player and composer from your time with the Revolution?

Oh wow. I don’t have a favorite moment, per se. I’m just lucky I had that experience, and I’m so lucky that guy was in my life, and that we did what we did. That’s what I’m proud of: that we did something powerful that was meaningful to all of us in the Revolution, and that it moved people. And that’s more apparent than ever when looking at the audiences for this tour.

From the clips I’ve watched, it seems to me this tour has been such a joyful celebration of the music and the man. I imagine it’s provided some serious closure for you as a confidant and collaborator.

It’s been a beautiful moment. We’re trying to let this awful loss for most people just land and we wanted to be together and we dug being together and that’s been the beauty of reuniting after all these years—unfortunately due to this awful, awful situation. But it has been beautiful for us to be together again with each other and this music.

Purple Rain in particular remains such a massively important work of art as an album. Do you have a favorite contribution to that record?

We spent months in a warehouse in Minneapolis just honing his ideas. He came in with his recipe and basically said, “I need to cook this, what are we going to do?” And that whole time, we all showed up and gave just our absolute best to those recipes and, to me, everything about it was just perfection. So it’s really hard to choose a single moment.

As someone who’s spent much of her career contributing guitar parts to pop music, and also witnessed the decline of guitar use in pop over the past few decades, do you have any advice to offer players interested in applying their guitar work in unexpected places in contemporary pop music?

If I was asked to play guitar on a Katy Perry record or something these days, I’d have to tell the producer that there’s just no room for it. Unless you want big power chords, I can do that, but otherwise, there’s just no room. The way pop songs are written these days, there’s 12 people with computers sitting in a room trying to mimic the latest chart-topping track, but make it just unique enough to get a pass. It’s ridiculous.

Hip-hop is the biggest commodity there is right now, and hip-hop has a better chance for interesting guitar. Anderson Paak does a really lovely job of it, for example. It’s such a vague time right now, I really don’t know. I don’t listen to pop music for guitar work anymore. Everything comes back around, though, so who knows?

On that note, is there anything that’s really turning you on right now as a producer and player in the gear world?

Well, because our tour is skin and bones, I profiled all of my boutique amps with my Kemper Profiling amp and it’s absolutely spectacular. I’m going straight through the board and all of my boutique amps are profiled perfectly. I absolutely love my little Top Hat amps. They’re just beautiful, and I’ve got great old Silvertones, and vintage Fender White Higher Fidelity amps that I use in the studio a lot, and all of them are profiled and good to go in the Kemper. I’m a small amp girl in the studio, and I just truly believe you get better sounds that way.

Your father was a studio musician and a member of the illustrious Wrecking Crew and played on records by Sinatra and a laundry list of other greats. Was he an influence on your path into studio work?

No, my dad didn’t influence me, actually! It was more my mother. My dad was really a worker. He was one of these session dudes that was out of the house from 9 in the morning until 9 at night doing three sessions a day—what they called “triples” back in the day. My mother was this huge music fan that sat me down in front of some speakers when I was kid and opened up the sheet music to things like The Rite of Spring and said stuff like “follow the cello part,” and I did, and it just blew my mind. She was the one that forced me to start guitar, and the only way she could get me to do it was to do the first two months with me, and then I was hooked in. I was six! So it was really more her that got me involved.

As far as other direct influences go, who was important to Wendy the guitarist?

That list is absolutely endless, and veers far away from just guitarists! Bowie, obviously, and the various people he had on guitar, like Mick Ronson, who might be my all-time favorite player. When I bought Mick Ronson’s first solo record and heard that song “Only After Dark,” that’s when I realized glam is funky, and can be so funky. Listen to the tone on that song and the way he played that rhythm part and tell me that guy wasn’t a genius.

YouTube It

Wendy Melvoin rocks her favorite ES-335 while the Revolution does a rousing rendition of “Computer Blue” live at B.B. King’s Blues Club in NYC in April 2017.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)