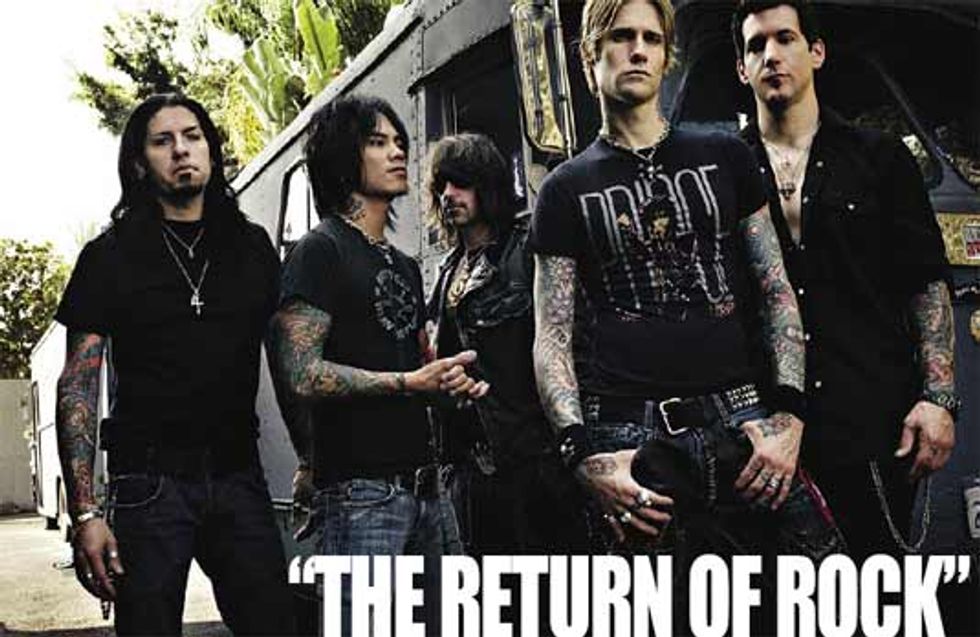

| Even if you don’t know them by name, Buckcherry is a band you’ve most likely caught yourself tapping a foot to – the rockers from L.A. have spent close to an entire decade on the charts with singles like, “Lit Up” and “Check Your Head”, and served as a refreshing, Les Paul-driven kick in the gut after emerging from the ashes of the late-‘90s pop music scene. When their third album, 15, dropped in April 2006, the hardest working band around earned comparisons to some of hard rock’s legends (read: AC/DC). The album’s first single, “Crazy Bitch,” was nominated for a Grammy for Best Hard Rock Performance, and that just hints at the raw, to-the-roots style of rock that Buckcherry cultivates on a daily basis. We caught up with guitarists Keith Nelson and Stevie D in the middle of their tour to talk about their unique sound and the gear that makes it happen. |

Your debut album came out in 1999. What was the musical environment like when you got the band together?

Keith: We really came up in the middle of rap rock and Lillith Fair. Swing music was also kind of happening at the time. Guys that slung Les Pauls low, and actually played them – that wasn’t really happening.

Was that discouraging at all for you guys?

Keith: When [lead singer] Josh and I got together, we talked about making just a straight-up rock band. I don’t think it was discouraging, but almost inspiring that we weren’t going to sound like everyone else.

In your reviews, it seems that an AC/DC reference is always dropped. How do you feel about that? Is that a big shadow to work under?

In your reviews, it seems that an AC/DC reference is always dropped. How do you feel about that? Is that a big shadow to work under? Stevie: For me, it’s a huge compliment. I’m a huge fan of the Young brothers and the blues that they touch on with their records, so anytime there’s a reference drawn like that, I’m really happy.

Keith: I always enjoy a comparison to a band that doesn’t suck. There’s a lot of nuance to that AC/DC reference that I don’t think a lot of people like. I’m a huge fan, and I have been since I was old enough to hoist a vinyl record on the turntable. They’re one of the few bands that can make the same record over and over and totally get away with it.

So were they one of the first bands that got you on your way to rock stardom?

Keith: Absolutely. I can remember one of my earliest experiences as a kid that loved music, and always being into music, as listening to Back in Black out of an old wooden stereo in my parent’s living room. I remember thinking to myself, “that just sounds evil and dark.” And they didn’t need “666” all over the record cover – the sound of Back in Black is just heavy, without being tuned down to C. It was life changing, for sure.

I just listened to your latest album, 15, for the second time and I’m hearing all kinds of influences, from rock to blues to country. Where do you guys pull those sounds from?

Stevie: Well, we’re all big blues fans – Jimmy [Ashhurst, bass] is well-versed in country and he’s our onboard rock n’ roll historian. I’ve learned a lot from each guy in this band, as far as the history of rock. For me, guys like Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters are tucked away in there. Keith has a lot of the chicken pickin’ and slide thing going on in his background. We try to cover a lot of that music, we’re trying to keep that going, and hopefully that’s what sets us apart from the other bands out there. Keith: I think we have so many things flying around the room, in terms of influences, in terms of country to funk and punk. If you listened to our iPods on the bus, you’ll hear all kinds of stuff. We’re really just fans of great music – for me, sounding bluesy isn’t a problem, the challenge is making it sound like it belongs in today’s music.

Stevie, you came on board a bit later in the band’s history. Do you have a role when you sit down to create songs?

Stevie: For me, it’s about creating space. It’s about not stepping on each other’s toes, and I think Keith feels the same way. Somebody will come into the room with a musical idea, and what we do is kind of let it play out. It’s like putting a skeleton in the room, and the job for the rest of us is to give that skeleton shape. A personality.

Do you feel like you guys are still evolving in your sound?

Keith: I think so. I think our first record was made so quickly, and the fact that we did it ourselves, and so I think our next records should be a bit deeper. Maybe we’ll spend three weeks in the studio instead of two.

I really dig the guitar tones coming off the album. How’d you get those sounds together?

Stevie: Keith has an arsenal of vintage amps, as well as our co-producer, Mike Plotnikoff. But what we used mostly on the record were Keith’s amps – for me, it was mostly a JTM45, but there were Plexis, Park amps … every vintage rock amp from the ‘60s and ‘70s was at our disposal.

Live, I’ve been using a Budda Superdrive 80. Open, loud and raw. It’s also got a great middle. In smaller rooms, I use the Superdrive 45 – they’re great. The Twinmaster is also a great combo amp, and it kicks the shit out of most other amps I’ve heard. I think they only made a limited number, and I managed to get my hands on one.

Keith: I have a pretty extensive gear collection, and I’ve been at it for a while. I usually try to go for the older stuff – I pretty much have every vintage Marshall, every vintage Vox you’ll need. But on 15, you’re hearing a lot of Super Lead 100s, a ‘66 JTM45, an old AC30 Top Boost and an armload of vintage guitars.

What guitars should we be listening for on your latest album?

Stevie: For me, I really connected with the JTM45. It was punchy, spanky and had a great bottom end. I coupled that with a ‘62 SG Junior. It’s been reworked with humbuckers, Gibson PAFs. I did leads with that same configuration and a Tube Screamer thrown in, or the Red Rooster pedal, for that wooly quality. I really like that wooly, ‘60s lead tone, like Hendrix. The clear ryhthms, on like a song like “Sorry,” I used a ‘62 reissue Strat.

Keith: On the album, I have an old Gretsch 6120 that I do a lot of the rhythm tracks with. I also have a ‘51 Esquire that’s on there a lot. Right before the record started, I went through a bit of a Strat phase, and picked up a ‘71 Strat that’s great. There’s also a lot of Les Paul Junior on the record.

So do you guys toy around with pedals or effects much? Or do you try to keep your signal clean?

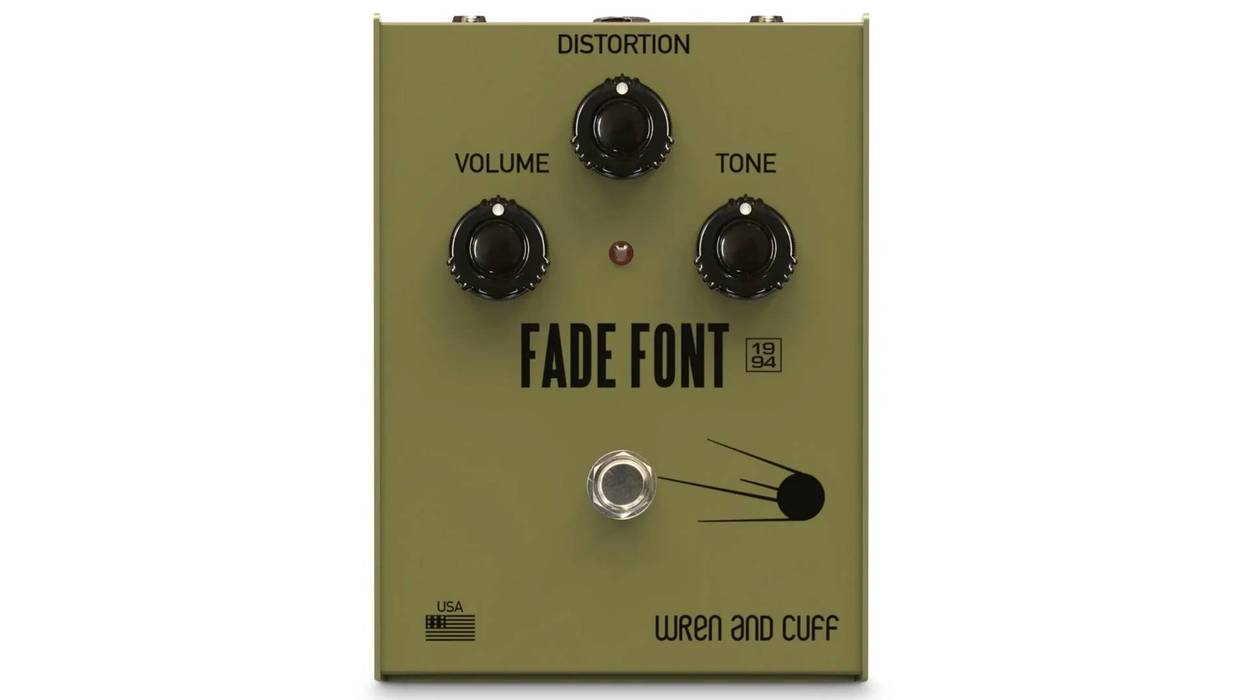

So do you guys toy around with pedals or effects much? Or do you try to keep your signal clean? Stevie: Not so much – in the studio, there’s not a lot of pedal effects for my side – I’m on the right side with the rhythms, Keith is on the left side [in the stereo spectrum], so you won’t hear a lot of effects on me. Live, I use a Tube Screamer and a wah pedal. Just recently, I switched to Budda, because they’re making such great pedals. br>

I try to keep it simple like that, because I feel like I’m jumping around so much, I can get confused if I have to hit a couple pedals at one time. Less is more for me anymore. I had some more pedals in the chain, but I just kind of found that it was too much. br>

Keith: I’m not a real big pedal guy. The guys at Keeley make these true bypass loopers, and I’ve been using that because I don’t really want anything in the way. And we still use cables, we’re not wireless.

Is there a reason you haven’t gone wireless?

Keith: It sounds better. I toyed with wireless a few years back, and every time I’d have a problem with the wireless, I’d plug the cable back in and just say, “damn, that sounds great!” Mogami cable is really solid.

Wrapping up, you guys kind of represent a younger generation of guys playing true rock and roll. Is there any advice you’ve picked up for people listening and trying to get into it?

Stevie: A lot of the bands we play with at festivals, they’re not learning to play their instruments like they used to. There’s very little emphasis placed on songwriting. So if you want to stand out, really learn your instrument, and learn about tone. Try out different things, and listen to a lot of records. Listen, listen, listen.

Keith: There are really two sides to it. On one side, we see these guys playing with tracks behind them. Really concentrate on being great players and performers, so you don’t have to rely on tracks behind you to pull it all off.

The other side is that this is all a business, so you need to educate yourself on how all the parts work together, otherwise it will be a long road.

| Stevie’s Gearbox When Stevie plugs in to rock out, here’s what he’s grabbing.

|

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)