Bassist and Union Leader Dave Pomeroy Makes Players’ Rights the Bottom Line in Nashville

Dave Pomeroy and a few of his best friends.

Organized labor has shaped the music we love, and Nashville Musicians Association president Dave Pomeroy believes musicians still need a fair deal.

“There’s always something to do in Nashville,” grins Dave Pomeroy. For Pomeroy, this is especially true. He’s the president of the Nashville Musicians Association (NMA), the city’s branch, or “local,” of the American Federation of Musicians (also known as AFM Local 257). The AFM is the largest musicians’ union in North America, representing around 70,000 music workers through more than 240 locals across the continent.

It’s no surprise that Music City’s local comes with a fair bit of history. Along with New York, Memphis, Chicago, and Los Angeles, Nashville is one of the most important cities in the trajectory of not only American music, but the business that shaped that music. As the recorded music and radio industries exploded in the 1940s and ’50s, musicians found themselves in uncharted waters. Suddenly, there were new and enormous revenue streams—royalties and record sales—and musicians weren’t getting their share. Record labels were getting fat off the surplus.

So, the AFM organized the biggest music workers’ direct action in history. For nearly two years between 1942 and 1944, the AFM’s roughly 136,000 members engaged in a recording ban: They refused to produce any new recordings for the record labels until they were guaranteed a fair cut of the new profits. Some top talents like Duke Ellington and Benny Goodman stood by the strikers. Others, like Frank Sinatra, scabbed, and used non-union musicians on their recordings when AFM musicians refused. (I guess that’s why it’s “My Way,” not “Our Way.”)

Dave Pomeroy & the All-Bass Orchestra: "Buckle Up"

The strikes were successful, though later challenges and divisions within the movement diminished the initial victories. Still, it showed that the collective power of organized labor could go toe-to-toe with corporations, and get what musicians are owed for the magic they create. Musicians nowadays, who are up “streaming creek” without a paddle, need as much help as they can get. “The music business doesn’t have to be a win-lose,” says Pomeroy. “It can be a win-win when everybody treats each other the right way.”

“The music business doesn’t have to be a win-lose. It can be a win-win when everybody treats each other the right way.”

Pomeroy was raised a military kid, born in Italy and later moving to England with his family in 1961. He got a head start on the Beatles, and stayed up late to watch them make their debut on The Ed Sullivan Show in February 1964. The Rolling Stones caught his ear just before his family uprooted to northern Virginia, where Pomeroy took piano lessons and played clarinet in the school band. He wanted to play the cello, but those spots were filled, so he took up the string bass at age 10. A couple years later, he discovered the bass guitar, which suited him just fine; he could dance around and sing with a bass hung across his shoulders. His parents helped him acquire a Gibson EB-2 (his hero Jack Bruce played Gibson basses, so he had to, too).

Pomeroy joined a folk trio in his second year at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, a turning point when he realized music was his destiny. He left school and moved to Belgium, where his parents were stationed at NATO. He quickly moved to London, where he played in five different bands in a year. Following a short stint in Denmark (his Hamburg, he quips) his European sabbatical was over, and it was time to get back stateside. One of his bandmates from Charlottesville had a publishing deal in Nashville, so Pomeroy decided to give it a go. That was 46 years ago.

Pomeroy hit the road with Don Williams in 1980, and quickly learned the value of mutual respect and fair working conditions.

Rockabilly icon Sleepy LaBeef gave Pomeroy his first gig. LaBeef was a human jukebox, and would switch up sets every night. The law of the band was simple: Follow, or die. It was a crash course in ear and style training for Pomeroy. He bounced around until he landed his big break: backing up Texas country slinger Don Williams. Pomeroy played in Williams’ band for 14 years, from 1980 to 1994, and that time would shape the rest of his life. It was an incredible musical education, and it bridged him to new worlds in the music industry.

But more than those things, it was the consideration that Williams showed his musicians that changed Pomeroy’s life. “He treated us with great respect,” he explains, “and I didn’t realize for some time that that was not the norm, and that it was a lot worse for a lot of my colleagues and friends.” At 24, Pomeroy co-wrote a song with Williams, who helped get him a publishing deal. Williams also landed his road band a record deal on his label ,MCA and co-produced their self-titled “Scratch Band” record.

“He treated us with great respect, and I didn’t realize for some time that that was not the norm, and that it was a lot worse for a lot of my colleagues and friends.”

Working with Williams cemented the value of documenting his work with a union contract. In 1980, Williams and his band played a show at Giant Stadium in East Rutherford, New Jersey. A month later, Pomeroy’s friend called to tell him to turn his TV on. The gig had been recorded for Casey Kasem’s America’s Top 10 program, and was airing. Pomeroy was over the moon, but things got even better—a short time later, he got a $1,000 check for the airing. When it aired again, he got another $1,000.

Dave Pomeroy's Gear

Over his 46 years in Nashville, Pomeroy has worked with the biggest stars of country and folk music. Emmylou Harris, performing with Pomeroy here in December 2023, brought him along to her sessions with the Chieftains in 1992.

Photo by Mickey Dobó

Basses

- Fleishman Custom 5-string electric upright

- 1967 Gibson EB-2

- G&L Fretted and fretless L-2000

- 1963 Fender Precision

- Alleva-Coppolo 5-string

- 1964 Framus Star Bass

- Reverend Rumblefish 4- and 5-strings

- Brad Houser 5-string

- 1980s Gibson Thunderbird fretted and fretless

- Lakland Jerry Scheff 5-string

- 1940s Kay

- Hamer 12-string

- Pedulla 8-string fretless

- Gold Tone Micro-Bass, Banjo, and Dobro

- Kala U-Basses – hollowbody and solidbody

- Jerry Jones 6-string baritone “tic-tac” bass

- Boulder Creek 4-string fretless and 5-string fretted acoustic basses

- Music Man 5-string

- Sadowsky 4-string

- Big Johnson – large acoustic fretted bass

Amps

- Genzler Magellan 800 Head with Genzler cabs

Effects

- Boss GT-10B

- Boss RC-50

- Boss RC-600

- SWR Mo’ Bass preamp

- Ampeg SVT preamp

- Line 6 Bass POD Pro

- Avalon U5 Class A Active Instrument DI and Preamp

- Trace Elliot V-Type preamp

- Morley wah pedal

- Morley volume pedal

Strings

- GHS Pressurewound, Brite Flats, Boomers, Flatwounds, and Round Cores

- Thomastick acoustic bass strings

“I thought, ‘Holy moly, this is how this stuff works?’” remembers Pomeroy. “There were so many times that we’d find out about these things with other artists, and nobody bothered to say anything; nobody turned it into paperwork. [They would say,] ‘Oh, I didn’t know we were supposed to get paid.’ I didn’t know we were supposed to get paid, but somebody took care of it. That was just the way Don was.”

Over the years, Pomeroy would perform and record with many celebrated artists, musicians, and songwriters in country, folk ,and bluegrass music, such as Earl Scruggs, Guy Clark, George Jones, Emmylou Harris, Chet Atkins, and Alison Krauss. He honed his voice on the instrument when he got an upright fretless electric bass, which he played on Keith Whitley’s 1988 record, Don’t Close Your Eyes. Pomeroy’s dramatic downward slide on “I’m No Stranger to the Rain” had his phone ringing off the hook. Harris invited him to play on her album, “Bluebird,” and he also joined her recording with The Chieftains in 1992, when she asked him to bring along “the bass from space,” her nickname for his electric upright. Pomeroy’s outside-of-the-box streak continued on his performances and arrangements of his song “The Day the Bass Players Took Over the World,” and his All-Bass Orchestra.

“They basically said, ‘Hey, these are our friends, and we’re not going to screw them over … We’re going to do this right.’”

Eventually, his path curved toward the studio world, where he started to take more notice of the local union’s role in making music. In the early 2000s, Pomeroy gravitated towards a subgroup of the AFM called the Recording Musicians Association, where he revived a sense of participation and engagement in negotiations. In 2008, he ran against the NMA’s incumbent president, Harold Bradley, who had held the post for 18 years. Pomeroy won the election, and has held the seat ever since.

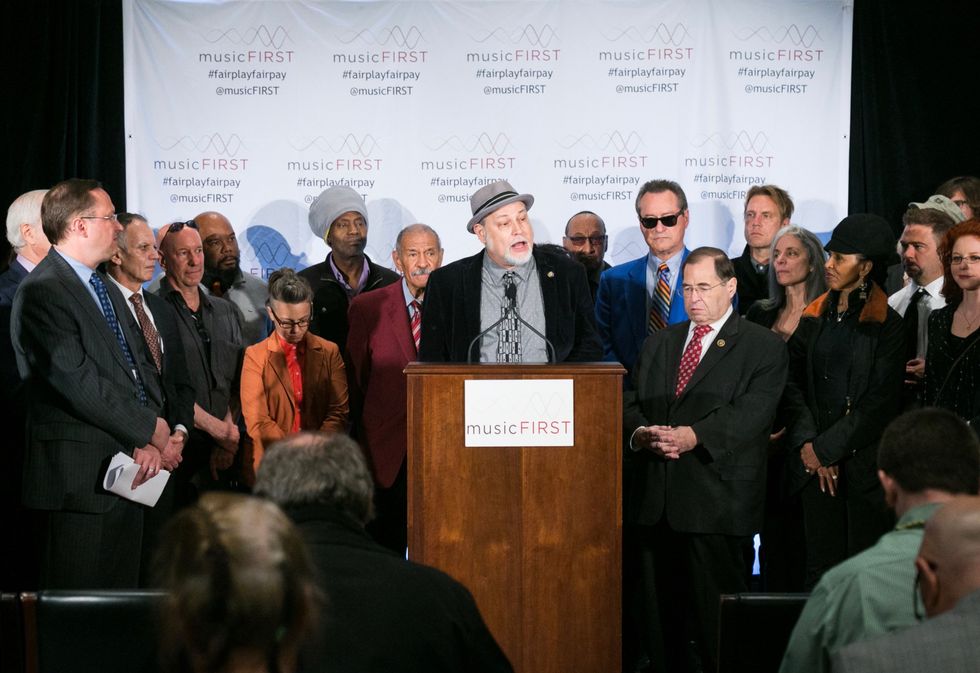

Pomeroy has advocated for better working conditions for artists for decades, including supporting the Fair Play Fair Pay Act in 2017, which addressed issues with terrestrial radio.

Photo courtesy of the Music First Coalition

The AFM’s single-song overdub scale agreement, a/k/a home studio contract, was created by NMA in 2012, and it wasn’t easy. There were drawn-out debates over where the pay floor should be. “Are we talking about ‘Mary Had a Little Lamb’ or are we talking about Mahler’s Symphony No. 6?,” says Pomeroy. The minimum, they decided, was $100, which can be negotiated upwards, depending on the difficulty of the job. But instead of simply being handing the player a crisp Benjamin, the employer would sign a piece of paper allowing the player to pay into their own pension, a first for AFM musicians.

The AFM “Tracks on Tour” contract was also a NMA creation. When Dolly Parton and Jason Aldean wanted to use recorded tracks onstage as part of their shows, they went to the NMA to work out how to do it right.

“I’m nice, but I’m also very persistent. I’m a Taurus. I’m not going to let things go. We’re going to work this out.”

Parton wanted a saxophone part in one of her songs without touring with a saxophonist, and Aldean wanted to use the acoustic guitar and piano from his hit ballad with Kelly Carson, “Don’t You Wanna Stay.” So, the NMA studied a Broadway touring show’s pay rates to come up with a scale for that situation, and the performers whose recorded work was being played earned up to $12,000 extra in a year, thanks to the formula. Some artists, says Pomeroy, can scheme their way around the scales by getting their road band to rerecord the parts for less money. “But a lot of artists are willing to pay to have the good stuff,” he says.

Pomeroy explains that at the start of its golden era, Nashville’s recording business was built on respect between employers and creators. Big labels like Decca and RCA Victor were run by Owen Bradley and Chet Atkins, respectively, and even though the labels wanted to turn a profit on “hillbilly music,” Bradley and Atkins were wise enough to know that they ought to give musicians a fair deal. “They basically said, ‘Hey, these are our friends, and we’re not going to screw them over. We got to play with them Saturday night at the country club, so we’re going to do this right, and do it on a union contract,’’ Pomeroy shares.

Pomeroy’s music and union work aren’t separate—they’re both part of a single vision, where artists can create and perform with dignity.

Photo by Jim McGuire

Sometimes, the dividends for doing this “right” are immediate and obvious. But other times, like Pomeroy experienced, they might take a little while to manifest. In 2014, Mazda used Patsy Cline’s “Back In Baby’s Arms” in a commercial for their new RX-7 car that ran for 2 years. A 90-year-old violinist who played in the song’s string section came into the NMA offices one day to pick up a New Use check for nearly $2,000. He told Pomeroy he’d been paid $57 to record his parts back in 1962. “That makes all the work worthwhile,” says Pomeroy.

A decent chunk of his work, says Pomeroy, falls into dealing with well-meaning people who might not have known they were shortchanging a musician, but need some reminding, all the same, to pony up. Other times, he and the AFM have to push a little harder to get musicians what they’re owed. “I chase people down,” says Pomeroy. “I’m nice, but I’m also very persistent. I’m a Taurus. I’m not going to let things go; we’re going to work this out.” Pomeroy says they’ve successfully sued for nearly a million dollars from employers who “didn’t want to do the right thing, and got to do the right thing the hard way.” Some of those people end up on Music City’s “Most Wanted”: the Nashville Musicians Association’s “Do Not Work For” list. It exists to warn both performers and the public about employers who are known to either break union contracts, or solicit union musicians to work outside a union contract.

All of this might seem separate or secondary to the actual creation and performance of music. But that belief, whether held subconsciously or expressed explicitly, is what has allowed musicians to remain overworked and underpaid for the past century, or more. If we really believe that music brings value to our lives, why shouldn’t the labor that enables its creation be supported fairly? And besides, musicians are workers like any other. If you saw a boss raking in stacks of cash while their employees struggled to make rent, you’d be pissed off, right? Well, that’s the situation a lot of music workers find themselves in these days. Pomeroy and the AFM have their work cut out for them.

But, it’s easier for Pomeroy when he sees a common ground between his music work and his union work. Sometimes, they collide, like on his song, “What Unions Did for You.” Each feeds and emboldens the other. “I have to have the creative stuff to balance out the administrative stuff,” says Pomeroy. “But in a lot of ways, the admin stuff that I do is a lot like being a bass player. You’re rushing, you’re dragging, it’s right here in the middle; let’s see if we can find that place where everybody’s gonna feel good.”

YouTube It

Dave Pomeroy bops through a solo performance of the riotous, bassman’s-rights tune “The Day the Bass Players Took Over the World” at the Country Music Hall of Fame.

- Jazz Bassist Scott Colley Talks About His Early Days ›

- Nashville’s Buddy Miller: From the Roots to the Cosmos ›

- Nashville Flood-Damaged Guitars Up For Auction ›

No matter what (or where) you are recording, organizing your files will save you hours of time.

A well-organized sample library is crucial for musicians, producers, and sound designers. It enables smoother workflows, saves time, and nurtures creativity by providing easy access to the perfect sounds.

Greetings, and welcome! Last month, I began the first of a multi-part Dojo series centered around field recording and making your own sound libraries by focusing on the recording process. This time, I’m going to show you ways to organize and create a library from the recordings you’ve made. We discover things by noticing patterns in nature, and we create things by imposing our own patterns back into nature as well. This is exactly what you’re doing by taking the uncontrolled, purely observant recordings you’ve made in the natural world and prepping them as raw material for new patterned, controlled forms of musical expression. Tighten up your belts, the Dojo is now open.

Easy Access Needs

Before you start diving in and heavily editing your recordings, identify what you have and determine how to categorize it for easy retrieval. A well-organized sample library is crucial for musicians, producers, and sound designers. It enables smoother workflows, saves time, and nurtures creativity by providing easy access to the perfect sounds. Whether you are starting from scratch or adding to an existing collection, a systematic approach can make a world of difference.

Take stock of your files, identify patterns, themes, and timbres, and then decide on potential categories for folders that make sense for your workflow. Typically, I will make dozens and dozens of raw recordings (empty stairwells, gently tapping two drinking glasses together, placing a contact mic on industrial equipment, etc.) and I will prearrange them into sub categories before I even start to edit. My top-level folders are: percussive and melodic. I may divide further depending on the source material.

For instance, recordings that could become drum hits can be separated into folders for kicks, snares, hi-hats, and percussion. Melodic information that might be used for one-shots or loops can be sorted by potential instrument type or key. This will save you hours of time later. For those who work with a specific genre, it can also be useful to group recordings by their possible stylistic context, like industrial, cinematic, or soundscapes.

Working with Raw Material

What are the best ways to start working with the raw recordings? First, make sure you have some way to edit them. Open your DAW and create a new session. Be sure to include the date and “raw recordings” in your session title and save the session. Next, import the file(s) into your DAW as a new audio track, or hardware sampler (for old schoolers). Then start listening for anything that ignites your imagination. Keep it short and pay attention to what you’re hearing. Ask yourself, “What would this be cool for?” Here’s a personal tip: Don’t delete everything that is not of immediate interest, just mute the sections that you’re not identifying with right now—they might become amazing once you start to process them with delays, reverb, and pitch shifting. Once you’ve got loads of appealing individual snippets and you’ve trimmed the start and ending for each one, you’re going to bounce or export each individual element to a specified folder on your hard drive. Now it’s time to think about file naming conventions.

“A well-organized sample library is crucial for musicians, producers, and sound designers.”

Clear and consistent file names are crucial. They ensure you can search for samples directly through your operating system or DAW without relying solely on folder hierarchies. Include lots of details like sample type, tempo, key, or sound source in the file name because it makes it easier to locate quickly in the future. For example, instead of naming a file “loop001.wav,” a more descriptive name like “Broken_Guitar_Arp_Raw.wav” provides instant context. I like using “Raw” at the end of my file name so I know it is in its original state. If you want to add processing like distortion, amp sims, modulation, and time-based effects, go ahead! Export each iteration with a new file name, e.g., “Broken_Guitar_Arp_TapeDelay.wav.”

Building a sample library isn’t just about organization—it’s also about curation. Remember that the quality of your library is waymore important than its size. Focus on making high-quality samples. Take the time to audition each of your recordings to weed out those of inferior sound quality. This decluttering process helps streamline your workflow and ensures that every file in your collection adds value.

Next month, I’ll guide you through ways to import and use your samples in your recording sessions. Namaste.

David Gilmour, making sounds barely contained by the walls of Madison Square Garden.

The voice of the guitar can make the unfamiliar familiar, expand the mind, and fill the heart with inspiration. Don’t be afraid to reach for sounds that elevate. A host of great players, and listening experiences, are available to inspire you.

In late fall, I had the good fortune of hearing David Gilmour and Adrian Belew live, within the same week. Although it’s been nearly two months now, I’m still buzzing. Why? Because I’m hooked on tone, and Gilmour and Belew craft some of the finest, most exciting guitar tones I’ve ever heard.

They’re wildly different players. Gilmour, essentially, takes blues-based guitar “outside”; Belew takes “outside” playing inside pop- and rock-song structures. Both are brilliant at mating the familiar and unfamiliar, which also makes the unfamiliar more acceptable to mainstream ears—thereby expanding what might be considered the “acceptable” vocabulary of guitar.

Belew was performing as part of the BEAT Tour, conjuring up the music of the highly influential King Crimson albums of the ’80s, and was playing with another powerful tone creator, Steve Vai, who had the unenviable role of tackling the parts of Crimson founder Robert Fripp, who is a truly inimitable guitarist. But Vai did a wonderful job, and his tones were, of course, superb.

To me, great tone is alive, breathing, and so huge and powerful it becomes an inspiring language. Its scope can barely be contained by a venue or an analog or digital medium. At Madison Square Garden, as Gilmour sustained some of his most majestic tones—those where his guitar sound is clean, growling, foreign, and comforting all at once—it felt as if what was emanating from his instrument and amps was permeating every centimeter of the building, like an incredibly powerful and gargantuan, but gentle, beast.

“The guitar becomes a kind of tuning fork that resonates with the sound of being alive.”

It certainly filled me in a way that was akin to a spiritual experience. I felt elevated, joyful, relieved of burdens—then, and now, as I recall the effect of those sounds. That is the magic of great tone: It transports us, soothes us, and maybe even enlightens us to new possibilities. And that effect doesn’t just happen live. Listen to Sonny Sharrock’s recording of “Promises Kept,” or Anthony Pirog soloing on the Messthetics’ Anthropocosmic Nest, or Jimi Hendrix’s “Freedom.” (Or, for that matter, any of the Hendrix studio recordings remixed and remastered under the sensibilities of John McDermott.) Then, there’s Jeff Beck’s Blow by Blow, and so many other recordings where the guitar becomes a kind of tuning fork that resonates with the sound of being alive. The psychoacoustic effects of great tones are undeniable and strong, and if we really love music, and remain open to all of its possibilities, we can feel them as tangibly as we feel the earth or the rays of the sun.

Sure, that might all sound very new age, but great tones are built from wood and wires and science and all the stuff that goes into a guitar. And into a signal chain. As you’ve noticed, this is our annual “Pro Pedalboards” issue, and I urge you to consider—or better yet, listen to—all the sounds the 21 guitarists in our keystone story create as you examine the pedals they use to help make them. Pathways to your own new sounds may present themselves, or at least a better understanding of how a carefully curated pedalboard can help create great tones, make the unfamiliar familiar, and maybe even be mind-expanding.

After all these years, some players still complain that pedals have no role other than to ruin a guitar’s natural tone. They are wrong. The tones of guitarists like Gilmour, Belew, Vai, Hendrix, Pirog, and many more prove that. The real truth about great tones, and pedals and other gear used with forethought and virtuosity, is that they are not really about guitar at all. They are about accessing and freeing imagination, about crafting sounds not previously or rarely heard in service of making the world a bigger, better, more joyful place. As Timothy Leary never said, when it comes to pedalboards and other tools of musical creativity, it’s time to turn on, tune up, and stretch out!

Follow along as we build a one-of-a-kind Strat featuring top-notch components, modern upgrades, and classic vibes. Plus, see how a vintage neck stacks up against a modern one in our tone test. Watch the demo and enter for your chance to win this custom guitar!

With 350W RMS, AMP TONE control, and custom Celestion speaker, the TONEX is designed to deliver "unmatched realism."

"The next step in its relentless pursuit of tonal perfection for studio and stage. Born from the same innovative drive that introduced the world's most advanced AI-based amp modeling, TONEX Cab ensures that every nuance of modern rigs shines onstage. It sets the new standard for FRFR powered cabinets for authentic amp tones, delivering unmatched realism to TONEX Tone Models or any other professional amp modeler or capture system."

Setting a New Standard

- Professional full-range flat-response (FRFR) powered cab for guitar

- True 350 W RMS / 700 W Peak with audiophile-grade power amps and advanced DSP control

- The most compact 12" power cab on the market, only 28 lbs. (12.7 kg)

- Exclusive AMP TONE control for amp-in-the-room feel and response

- Custom Celestion 12'' guitar speaker and 1'' high-performance compression driver

- 132 dB Max SPL for exceptional punch and clarity on any stage

- Programmable 3-band EQ, custom IR loader with 8 onboard presets and software editor

- Inputs: XLR/1/4" combo jack Main and AUX inputs, MIDI I/O and USB

- Output: XLR output (Pre/Post processing) for FOH or cab linking, GND lift

- Durable wood construction with elegant design and finish

- Swappable grill cloths (sold separately) and integrated tilt-back legs

Finally, Amp-in-the-room Tone and Feel

Thanks to its unique DSP algorithms, TONEX Cab's exclusive AMP TONE control stands apart from any other FRFR in the market today, allowing players to dial in the perfect amount of real amp feel and response to any room or venue.

It achieves this through advanced algorithmic control over the custom high-wattage Celestion 12'' guitar speaker and 1'' high-performance compression driver. Together, they deliver the optimal resonance and sound dispersion players expect from a real cab. Combined with a wood cabinet, this creates a playing experience that feels alive and responsive, where every note blooms and sustains just like a traditional amp.

Ultra-portable and Powerful

TONEX Cab is the most compact 12'' powered cab in its class, leaving extra room in the car to pack two for stereo or to travel lighter. Despite its minimal size, the TONEX Cab delivers true 350 W RMS / 700 W Peak Class-D power. Its unique DSP control provides true-amp sound at any volume, reaching an astonishing 132 dB Max SPL for low-end punch and clarity at any volume. With larger venues, the XLR output can link multiple cabs for even more volume and sound dispersion.

Amplify Any Rig Anywhere

TONEX Cab is the perfect companion for amplifying the tonal richness, dynamics and feel of TONEX Tone Models and other digital amp sims. It adds muscle, articulation, and a rich multi-dimensional sound to make playing live an electrifying and immersive experience.

Its onboard IR loader lets players connect analog preamps directly to the cab or save DSP power by removing the modeler's IR block. Precision drivers also work perfectly with acoustic guitars and other audio instruments, ensuring that time-based effects shine with studio-quality clarity and detail.

Pro-level Features

TONEX Cab offers plug-and-play simplicity with additional pro features for more complex rigs. Features include a 3-band EQ for quickly dialing in your tone to a specific room without editing each preset. You can program the eight memory slots to store both EQ and AMP TONE settings, plus your cabinet IR selection using the onboard controls or the included TONEX Cab Control software. Seamlessly select between memory slots with the onboard PRESET selector or via the built-in MIDI I/O.

On Stage to FOH

TONEX Cab's balanced audio output makes it easy to customize the stage or house sound. It features pre- or post-EQ/IR for cab linking or sending sound to the front-of-house (FOH). The AUX IN allows users to monitor a band mix or play backing tracks. These flexible routing options are ideal for fine-tuning the setup at each gig, big or small.

Stereo and Stacking

With two or more TONEX Cabs, any rig becomes even more versatile. A dual TONEX pedal rig creates a lush, immersive tone with spacious, time-based effects. Players can also build a wet/dry or wet/dry/wet rig to precisely control the direct/FX mix, keeping the core tone intact while letting the wet effects add depth and space. Stack multiple cabs for a massive wall of sound and increased headroom to ensure the tone stays punchy and powerful, no matter the venue size.

Designed to Inspire

The TONEX Cab's Italian design and finish give it a timeless yet modern look under any spotlight. The integrated tilt-back legs let users angle the cab and direct the sound, which is optimal for hearing better in small or dense sound stages. Swappable optional grills (Gold/Silver) make it easy to customize each rig's appearance or keep track of different TONEX Cabs between bandmates or when running stereo rigs.

Bundled Software

TONEX Cab includes a dedicated TONEX Cab Control software application for managing and loading presets and IRs. As part of the TONEX ecosystem, it also includes TONEX SE, the most popular capture software program, with 200 Premium Tone Models, unlimited user downloads via ToneNET and AmpliTube SE for a complete tone-shaping experience.

Pricing and Availability

TONEX Cab is now available for pre-order from the IK online store and IK dealers worldwide at a special pre-order price of $/€699.99 (reg. MSRP $/€799.99*) with a black grill as the default. The optional gold and silver grill cloths are available at a special pre-order price of $/€39.99 (reg. MSRP $/€49.99*). Introductory pricing will end on March 18, with TONEX Cab shipping in April.

*Pricing excluding tax.

For more information, please visit ikmultimedia.com